The Biology of the Estuary'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Flood Defences - Groynes

Coastal Flood Defences - Groynes Coastal flood defences are key to protecting our coasts against flooding, which is when normally dry, low lying flat land is inundated by sea water. Hard engineering methods are forms of coastal flood defences which mitigate the risk of flooding and coastal erosion and the consequential effects. Hard Engineering Hard engineering methods are often used as a temporary measure to protect against coastal flooding as they are costly and only last for a relatively short amount of time before they require maintenance. However, they are very effective at protecting the coastline in the short-term as they are immediately effective as opposed to some longer term soft engineering methods. But they are often intrusive and can cause issues elsewhere at other areas along the coastline. Groynes are low lying wood or concrete structures which are situated out to sea from the shore. They are designed to trap sediment, dissipate wave energy and restrict the transfer of sediment away from the beach through long shore drift. Longshore drift is caused when prevailing winds blow waves across the shore at an angle which carries sediment along the beach.Groynes prevent this process and therefore, slow the process of erosion at the shore. They can also be permeable or impermeable, permeable groynes allow some sediment to pass through and some longshore drift to take place. However, impermeable groynes are solid and prevent the transfer of any sediment. Advantages and Disadvantages +Groynes are easy to construct. +They have long term durability and are low maintenance. +They reduce the need for the beach to be maintained through beach nourishment and the recycling of sand. -

1 the Influence of Groyne Fields and Other Hard Defences on the Shoreline Configuration

1 The Influence of Groyne Fields and Other Hard Defences on the Shoreline Configuration 2 of Soft Cliff Coastlines 3 4 Sally Brown1*, Max Barton1, Robert J Nicholls1 5 6 1. Faculty of Engineering and the Environment, University of Southampton, 7 University Road, Highfield, Southampton, UK. S017 1BJ. 8 9 * Sally Brown ([email protected], Telephone: +44(0)2380 594796). 10 11 Abstract: Building defences, such as groynes, on eroding soft cliff coastlines alters the 12 sediment budget, changing the shoreline configuration adjacent to defences. On the 13 down-drift side, the coastline is set-back. This is often believed to be caused by increased 14 erosion via the ‘terminal groyne effect’, resulting in rapid land loss. This paper examines 15 whether the terminal groyne effect always occurs down-drift post defence construction 16 (i.e. whether or not the retreat rate increases down-drift) through case study analysis. 17 18 Nine cases were analysed at Holderness and Christchurch Bay, England. Seven out of 19 nine sites experienced an increase in down-drift retreat rates. For the two remaining sites, 20 retreat rates remained constant after construction, probably as a sediment deficit already 21 existed prior to construction or as sediment movement was restricted further down-drift. 22 For these two sites, a set-back still evolved, leading to the erroneous perception that a 23 terminal groyne effect had developed. Additionally, seven of the nine sites developed a 24 set back up-drift of the initial groyne, leading to the defended sections of coast acting as 1 25 a hard headland, inhabiting long-shore drift. -

NJ Art Reef Publisher

Participating Organizations Alliance for a Living Ocean American Littoral Society Clean Ocean Action www.CleanOceanAction.org Arthur Kill Coalition Asbury Park Fishing Club Bayberry Garden Club Bayshore Saltwater Flyrodders Main Office Institute of Coastal Education Belford Seafood Co-op Belmar Fishing Club 18 Hartshorne Drive 3419 Pacific Avenue Beneath The Sea P.O. Box 505, Sandy Hook P.O. Box 1098 Bergen Save the Watershed Action Network Wildwood, NJ 08260-7098 Berkeley Shores Homeowners Civic Association Highlands, NJ 07732-0505 Cape May Environmental Commission Voice: 732-872-0111 Voice: 609-729-9262 Central Jersey Anglers Ocean Advocacy Fax: 732-872-8041 Fax: 609-729-1091 Citizens Conservation Council of Ocean County Since 1984 Clean Air Campaign [email protected] [email protected] Coalition Against Toxics Coalition for Peace & Justice Coastal Jersey Parrot Head Club Coast Alliance Communication Workers of America, Local 1034 Concerned Businesses of COA Concerned Citizens of Bensonhurst Concerned Citizens of COA Concerned Citizens of Montauk Dosil’s Sea Roamers Eastern Monmouth Chamber of Commerce Environmental Response Network Bill Figley, Reef Coordinator Explorers Dive Club Fisheries Defense Fund NJ Division of Fish and Wildlife Fishermen’s Dock Cooperative Fisher’s Island Conservancy P.O. Box 418 Friends of Island Beach State Park Friends of Liberty State Park Friends of Long Island Sound Port Republic, NJ 08241 Friends of the Boardwalk Garden Club of Englewood Garden Club of Fair Haven December 6, 2004 Garden Club of Long Beach Island Garden Club of Morristown Garden Club of Navesink Garden Club of New Jersey RE: New Jersey Draft Artificial Reef Plan Garden Club of New Vernon Garden Club of Oceanport Garden Club of Princeton Garden Club of Ridgewood VIA FASCIMILE Garden Club of Rumson Garden Club of Short Hills Garden Club of Shrewsbury Garden Club of Spring Lake Dear Mr. -

Nh-Connect-The-Coast-Report.Pdf

Connect THE Coast LINKING WILDLIFE ACROSS NEW HAMPSHIRE’S SEACOAST AND BEYOND Final Report: 10/31/2019 Authors: Peter Steckler and Dea Brickner-Wood Connect THE Coast LINKING WILDLIFE ACROSS NEW HAMPSHIRE’S SEACOAST AND BEYOND FINAL REPORT 10/31/2019 Authors Peter Steckler GIS & Conservation Project Manager The Nature Conservancy, New Hampshire Dea Brickner-Wood Coordinator Great Bay Resource Protection Partnership Cite plan as: Steckler, P and Brickner-Wood, D. 2019. Connect The Coast final report. The Nature Conservancy and the Great Bay Resource Protection Partnership. Concord, NH. Cover: Map of New Hampshire’s Coastal watershed, created by The Nature Conservancy. Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ i Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... ii 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Project Area .............................................................................................................................. 1 Conservation Context ............................................................................................................... 3 Historic Context of Land Use in the Coastal Watershed ........................................................ 4 Current Connectivity Challenges -

Coastal Upwelling in the Eastern Gulf of California

OCEANOLOGICA ACTA · VOL. 23 – N° 6 Coastal upwelling in the eastern Gulf of California Salvador-Emilio LLUCH-COTA * Centro de Investigaciones Biolo´gicas del Noroeste, S.C. PO Box 128 La Paz, BCS, Me´xico 23000 Received 11 May 1999; revised 8 December 1999; accepted 13 December 1999 Abstract – Understanding and quantifying upwelling is of great importance for marine resource management. Direct measurement of this process is extremely difficult and observed time-series do not exist. However, proxies are commonly derived from different data; most commonly wind-derived. A local wind-derived coastal upwelling index (CUI) is reported for the period 1970–1996 and is considered representative for the eastern central Gulf of California, an important fishing area where no proxies exist. The index is well related to pigment concentration distribution, surface water temperature, and population dynamics of important fish resources over the seasonal time-scale. There is a biological response to ENSO activity not reflected by this index, indicating that improvement of biological enrichment forecasting also requires water column structure input. A clearly increasing seasonal amplitude signal is detected in the coastal upwelling index and sea surface temperature since the mid 1970s. Understanding the nature of these long-term trends, the incorporation of remote tropical ocean signals into the enrichment proxy, the dynamics of atmosphere and ocean, and the biological responses are major challenges to the proper management of fish resources in the Gulf of California. upwelling / Gulf of California / seasonality / climate change Re´sume´–Upwelling coˆtier dans l’est du golfe de Californie. Comprendre et e´valuer le phe´nome`ne d’upwelling est tre`s important pour la gestion des ressources marines. -

Sediment Characteristics and Intertidal Beach Slopes Along the Jiangsu Coast, China

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Sediment Characteristics and Intertidal Beach Slopes along the Jiangsu Coast, China Yu Kuai 1,* , Jianfeng Tao 2,* , Zaiyang Zhou 1,3 , Stefan Aarninkhof 1 and Zheng Bing Wang 1,4 1 Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Delft University of Technology, 2628 CN Delft, The Netherlands; [email protected] (Z.Z.); [email protected] (S.A.); [email protected] (Z.B.W.) 2 College of Harbor, Coastal and Offshore Engineering, Hohai University, Nanjing 210098, China 3 State Key Laboratory of Estuarine and Coastal Research, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200062, China 4 Marine and Coastal Systems Department, Deltares, 2600 MH Delft, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected] (Y.K.); [email protected] (J.T.) Abstract: Tidal flats play an important role in promoting coastal biodiversity, defense against flood- ing, land reclamation and recreation. Many coastal tidal flats, especially the tide-dominant ones, are muddy. However, the number of studies on the profile shape and surficial sediment distribu- tion of muddy tidal flats is small compared to sandy beaches. Based on high spatial-resolution measurements along the tide-dominant Jiangsu Coast, China, we analyzed the morphology and sediment characteristics of the unvegetated intertidal flats along the Jiangsu Coast. The Jiangsu Coast can be divided into an eroding northern part (north coast) and an accreting southern part (south coast). The beach slope of the north coast shows a southward flattening trend, apart from some outliers related to rocky parts of the coastline. We found alternating very fine and coarse sediment (depending on the local clay content) for different locations along the north coast, which can be explained from consolidation and armoring-induced erosion resistance. -

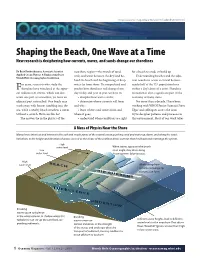

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast. -

1 PILOT PROJECT SAND GROYNES DELFLAND COAST R. Hoekstra1

PILOT PROJECT SAND GROYNES DELFLAND COAST R. Hoekstra1, D.J.R. Walstra1,2 , C.S Swinkels1 In October and November 2009 a pilot project has been executed at the Delfland Coast in the Netherlands, constructing three small sandy headlands called Sand Groynes. Sand Groynes are nourished from the shore in seaward direction and anticipated to redistribute in the alongshore due to the impact of waves and currents to create the sediment buffer in the upper shoreface. The results presented in this paper intend to contribute to the assessment of Sand Groynes as a commonly applied nourishment method to maintain sandy coastlines. The morphological evolution of the Sand Groynes has been monitored by regularly conducting bathymetry surveys, resulting in a series of available bathymetry surveys. It is observed that the Sand Groynes have been redistributed in the alongshore, mainly in northward direction driven by dominant southwesterly wave conditions. Furthermore, data analysis suggests that Sand Groynes have a trapping capacity for alongshore supplied sand originating from upstream located Sand Groynes. A Delft3D numerical model has been set up to verify whether the morphological evolution of Sand Groynes can be properly hindcasted. Although the model has been set up in 2DH mode, hindcast results show good agreement with the morphological evolution of Sand Groynes based on field data. Trends of alongshore redistribution of Sand Groynes are well reproduced. Still the model performance could be improved, for instance by implementation of 3D velocity patterns and by a more accurate schematization of sediment characteristics. Keywords: Sand Groyne, Delfland Coast, sand nourishment, sediment transport, Delft3D INTRODUCTION Objective The main objective of this paper is to asses an innovative sand nourishment method to maintain a sandy coastline, by constructing small sandy headlands in the upper shoreface called Sand Groynes (see Figure 1). -

Biodiversity of the Caribbean

Biodiversity of the Caribbean A Learning Resource Prepared For: (Protecting the Eastern Caribbean Region’s Biodiversity Project) Photo supplied by: Andrew Ross (Seascape Caribbean) Part 2 / Section C Coral Reef Ecosystems February 2009 Prepared by Ekos Communications, Inc. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada [Part 2/Section C] Coral Reef Ecosystems Table of Contents C.1. What is a Coral Reef Ecosystem? C.2. Formation of Coral Reefs C.3. Types of Coral Reefs C.4. Species Biodiversity C.5. Importance of Coral Reefs C.5.a. Food Source and Habitat C.5.b. Water Filtration C.5.c. Fisheries C.5.d. Tourism C.5.e. Coastal Protection C.5.f. Source of Scientific Advances C.5.g. Intrinsic Value C.6. Types of Human & Natural Impacts C.6.a. Pollution C.6.b. Over-fishing C.6.c. Tourism C.6.d. Sedimentation C.6.e. Mining Reef Resources C.6.f. Climate Change C.7. Protecting Coral Reefs C.8. Student Fact Sheet: Fifty Facts About Wider Caribbean Coral Reefs C.9. Case Study: Tobago Cays Marine Park (TCMP), Southern Grenadines C.10. Activity 1: Mock Marine Management Plan C.11. Activity 2: Coral Reef Ecosystem Poster Presentation C.12. Case Study: Community-Based Natural Resource Management in the Bay Islands, Honduras C.13. Activity 3: Diagram the Case! C.14. References [Part 2/Section C] Coral Reef Ecosystems C.1. What is a Coral Reef Ecosystem? 30°C. Tropical corals are found within three main regions of the Coral reefs exist in the warm, clear, shallow waters of tropical world: the Indo-Pacific, the Western North Atlantic, and the Red oceans worldwide but also in the cold waters of the deep seas. -

Guide to Fishing and Diving New Jersey Reefs

A GUIDE TO THIRD EDITION FISHING AND DIVING NEW JERSEY REEFS Revised and Updated DGPS charts of NJ’s 17 reef network sites, including 3 new sites Over 4,000 patch reefs deployed A GUIDE TO FISHING AND DIVING NEW JERSEY REEFS Prepared by: Jennifer Resciniti Chris Handel Chris FitzSimmons Hugh Carberry Edited by: Stacey Reap New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Division of Fish and Wildlife Bureau of Marine Fisheries Reef Program Third Edition: Revised and Updated Cover Photos: Top: Sinking of Joan LaRie III on the Axel Carlson Reef. Lower left: Deploying a prefabricated reef ball. Lower right: Bill Figley (Ret. NJ Reef Coordinator) holding a black sea bass. Acknowledgements The accomplishments of New Jersey's Reef Program over the past 25 years would not have been possible with out the cooperative efforts of many government agencies, companies, organizations, and a countless number of individuals. Their contributions to the program have included financial and material donations and a variety of services and information. Many sponsors are listed in the Reef Coordinate section of this book. The success of the state-run program is in large part due to their contributions. New Jersey Reef Program Administration State of New Jersey Jon S. Corzine, Governor Department of Environmental Protection Mark N. Mauriello, Acting Commissioner John S. Watson, Deputy Commissioner Amy S. Cradic, Assistant Commissioner Division of Fish and Wildlife David Chanda, Director Thomas McCloy, Marine Fisheries Administrator Brandon Muffley, Chief, Marine Fisheries Hugh Carberry, Reef Program Coordinator Participating Agencies The following agencies have worked together to make New Jersey's Reef Program a success: FEDERAL COUNTY U.S. -

Application of Timber Groynes in Coastal Engineering

Application of timber groynes in coastal engineering M.Sc. Thesis U.H. Perdok December 2002 Application of timber groynes in coastal engineering Draft M.Sc. Thesis U.H. Perdok December 2002 Section of Hydraulic Engineering Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences Delft University of Technology Thesis committee: Mr. M.P. Crossman, HR Wallingford Ltd Dr. ir. A.L.A. Fraaij, Delft University of Technology Mr. J.D. Simm, HR Wallingford Ltd Prof. dr. ir. M.J.F. Stive, Delft University of Technology Ir. H.J. Verhagen, Delft University of Technology Cover picture: Severely abraded timber groyne at Bexhill, East Sussex, UK (April 2002) ii Preface This thesis presents the results of my graduation project and will lead to the completion of the Masters of Science degree in Civil Engineering at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Delft University of Technology (The Netherlands). With this thesis I hope to provide with guidance on the use of timber groynes in coastal engineering and to promote the appropriate use of available timber. I was privileged to execute the major part of this research project at Hydraulics Research Wallingford (United Kingdom) during a six-month placement period. While working on the “Manual on the use of timber in coastal and fluvial engineering”, I had the opportunity to learn from the experience of contractors, consultants, local authorities and timber specialists. As this report is largely based on their experience, I would like to thank the following people for their cooperation: Simon Howard and John Andrews (Posford-Haskoning), Andrew Bradbury (New Forest District Council), Brian Holland (Arun District Council), David Harlow (Bournemouth Borough Council), Stephen McFarland (Canterbury City Council) and John Williams (TRADA). -

LAW of the SEA (National Legislation) © DOALOS/OLA

Page 1 Decree of 28 August 1968 delimiting the Mexican Territorial Sea within the Gulf of California ... Sole article The Mexican territorial sea within the Gulf of California shall be measured from a baseline drawn as follows: 1. Along the western coast of the Gulf, from the point known as Punta Arena in the Territory of Baja California, in a north-westerly direction along the low-water mark to the point known as Punta Arena de la Ventana; thence along a straight baseline to the point known as Roca Montaña at the southern extremity of Cerralvo Island; thence along the low-water mark of the eastern shore of the said island to the northern extremity of the same; thence along a straight baseline to Las Focas Reef; thence along a straight baseline to the easternmost point of Espíritu Santo Island; thence along the eastern shore of the said island to the northernmost point of the same; thence along a straight baseline to the south-eastern extremity of La Partida Island; thence along the western shore of the said island to the group of islets known as Los Islotes at the northern extremity of La Partida Island; from the northern extremity of the said islets along a straight baseline to the south-eastern extremity of San José Island; thence in a general northerly direction along the low-water mark of the eastern shore to the point at which the shore of the island changes direction towards the north-west; from that point along a straight baseline to the island known as Las Animas; from the northern extremity of the said island along a straight