LUDWIG BÖRNE How to Become an Original Writer in Three Days

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This List Is Meant for Reference Only – All Credits Below Should Be

LIST OF ACCEPTABLE CREDITS --- TELEVISION & DIGITAL MEDIA CATEGORIES This list is meant for reference only – all credits below should be considered eligible, unless otherwise specified in the 2018 Canadian Screen Awards TV and Digital Media Rules & Regulations booklet Appeals will be considered by the Awards Director for any credits not listed here. The production company may submit a letter stating why they feel the entrant should be included, as well as an explanation of their role in the production; this letter should be addressed to Louis Calabro, Director, Awards & Special Events. Please Note: Not all categories are listed in this document. Program Categories (not including DDDigitalDigital MMMedia,Media, NNNewsNews and SSSports)Sports) Executive Producer Executive Producer For (broadcaster) Co-Executive Producer Producer or Produced by Supervising Producer Series Producer Senior Producer (for informational / doc / talk shows / sports / “analytical” programming) Commissioning Editor (for informational / doc / talk shows / sports / “analytical” programming) Senior Executive Producer (for in house documentaries and broadcaster produced shows only) Episode Producer Content Producer For Best Factual Program or Series (1026) – Director or Producer eligible Note: For all Doc PROGRAM categories (Not Series) – “Director” is eligible Digital Media, News, Sports and Research Categories Any credit may enter, unless otherwise stated in Rules & Regulations booklet Directing (2001 ––– 2013) Only 2 entrants for this category. Any additional names -

How to Find Your Readers As a Fiction Writer

How to find Your readers as a fiction writer a 4-step workbook to walk4 you through finding your readership online Many fiction writers believe that they don’t need a platform. And while it’s true that literary agents and editors don’t expect aspiring novelists to have platforms, it’s just as true that writers must know how to find their readers if they want long-term success. Unfortunately, a lack of familiarity with the online landscape and a discomfort with putting creative work out there can cripple even the most promising book launch. This workbook will show you how to start putting your work in front of potential readers now, so that you can earn the trust and goodwill of the readership your work deserves. Building an author platform will allow you to: Sell more copies of existing books with less effort Launch a new book (or other content) successfully Get to know your readers so you can serve them better Avoid burnout so that book marketing is sustainable and rewarding Make a living as a full-time writer step 1: you Writing anything--whether it’s a novel or a tweet--starts with you. A platform will be meaningless drudgery if it doesn’t revolve around topics you love to talk about and read about. So here’s a chance to visualize yourself just as clearly as you would your next main character. This charac- ter sketch will help you pull up all the words that define you and lay them out visually, so you can inspect them as a whole. -

Program Overview Screenwriting Research Network

Program Overview Screenwriting Research Network 7. International Conference 17—19 October 2014 Screenwriting and Directing Audiovisual Media Keynotes by Milcho Manchevski, Jutta Brückner & Brian Winston Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, Potsdam, Germany FILMUNIVERSITÄT BABELSBERG KONRAD WOLF Conference website: www.filmuniversitaet.de/de/forschung/tagungen-symposien/tagungen/tma/detail/6706.html Thursday, 16 October 3 —5 pm Sightseeing: Potsdam Park Sanssouci www.potsdam-park-sanssouci.de/sitemap-eng.html We organized a guided tour of Sanssouci (castle and park) Thursday afternoon, October 16th, 3-5 pm. The tour is in English language with access for a group of max. 40 entrants. The fee must be shared: depending on the number of participants it could be 9,50 Euro each (40p.) up to 19 Euro (20p.) Please sign in: http://doodle.com/qyyrf69hu7yis9m8 6—9 pm Opening Reception & Get Together @ Wissenschaftsetage Potsdam (rsvp) Bildungsforum Potsdam, Am Kanal 47, 14467 Potsdam (4th floor) > www.wis-potsdam.de/en Friday, 17 October 9 am Registration (entrance hall, first floor) 10 am Welcome by PROFESSOR DR. SUSANNE STÜRMER, PRESIDENT OF FILM UNIVERSITY BABELSBERG KONRAD WOLF, PROFESSOR DR. KERSTIN STUTTERHEIM, CONFERENCE HOST AND KIRSI RINNE, CHAIR SRN 10:30 am Keynote by MILCHO MANCHEVSKI: WHY I LIKE WRITING AND HATE DIRECTING: NOTES OF A RECOVERING WRITER-DIRECTOR (Writer/Director, Scholar, Macedonia/USA) 11:30 am Coffee Break 11:45 am—1:15 pm Panel 1: WRITER–DIRECTOR’S SCREENPLAYS Ian W. Macdonald (University of Leeds, UK) SCREENWRITING AND SUBJECTIVITY Carmen Sofia Brenes (University of Los Andes, Chile) THE POETIC DENSITY OF THE STORY AS KEY ISSUE IN THE FILM NEGOTIATION BETWEEN WRITER, DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER Temenuga Trifonova (York University, Canada) THE WRITER’S SCREENPLAY AND THE WRITER/DIRECTOR’S SCREENPLAY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS Jarmo Lampela (Aalto University Helsinki, Finland) ENSEMBLE AS A SCRENWRITER – THEATRE GOES MOVIES Panel 2: AUTEUR–FILM Gabriel M. -

Translating the Exiled Self: Reflections on Translation and Censorship*

Intercultural Communication Studies XIV: 4 2005 Samar Attar TRANSLATING THE EXILED SELF: REFLECTIONS ON TRANSLATION AND CENSORSHIP* Samar Attar Independent Researcher Self-Translating and censorship Translators tend to select foreign literary texts for translation into their mother-tongue for different reasons. Sometimes, their selection is based on the fame of a certain writer among his or her own people, or for the awarding of a prestigious international prize to a writer, or on the recommendation of an authoritative figure: a scholar, a critic, or a publisher. At other times, however, the opposite can be true. A writer who is not known among his or her own people is translated into another language, because his or her writing subverts the values of the national tradition, or destroys certain clichés about other nations, or simply because his or her work appeals to the translator.1 But we should not entertain the illusion that literary translators are always free agents. Although their literary taste and ideology may play an important role in their selection of foreign texts they often have to consider the literary, political and economic climate of their time. They simply do not translate texts because they like them. They are very much aware of the fact that translation cannot be brought to a fruitful end unless other authoritative bodies support them, and unless a publisher is found at the end of the ordeal. In short, personal, literary, social, political and economic factors always play an important role in the selection and translation of a foreign text. Normally the literary translator, who selects or is helped in selecting a foreign text, is expected to be a master of at least two languages including his or her own native tongue. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

NAB's Guide to Careers in Television

NAB’s Guide to Careers in Television Second Edition by Liz Chuday TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents…………………………………..……………………......... 1-3 Introduction………………………………………………………………... ......... 4 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………....... 6 A Word About Station Ownership………………..…………… ..................…7 The General Administration Department…………………. ...................... 8-9 General Manager……………..……………….……………… ..................... 8 Station Manager……..…………………………………………….. .............. 8 Human Resources…………………………..………………........................ 8 Executive Assistant…………………………..…………………… ............... 9 Business Manager/Controller…………………………… ........................... 9 The Sales and Marketing Department………………………….............. 10-11 Director of Sales…………………..………………………….. ................... 10 General Sales Manager…………………………………………................ 10 National Sales Manager……...……………………..……......................... 10 Marketing Director or Director of Non-Traditional Revenue……….……………...................... 10 Local Sales Manager..……………………………………………. ............. 11 Account Executive..……………………….………………………............. .11 Sales Assistant..………………………….…………………………............ 11 The Traffic Department………………..…………………………................... 12 Operations Manager…………………………………………..................... 12 Traffic Manager…………………………………….………………. ............ 12 Traffic Supervisor………………………………….……………….............. 12 Traffic Assistant…………………………………………….………............. 12 Order Entry Coordinator/Log Editors………………………. .................... 12 The Research Department………………………………………. -

Glossary of Filmmaker Terms

Above the Line Clapboard Generally the portion of a film's budget that covers A small black or white board with a hinged stick on the costs associated with major creative talent: the top that displays identifying information for each shot stars, the director, the producer(s) and the writer(s). in the movie. Assists with organizing shots during (See also Below the Line) editing process; the clap of the stick allows easier Art Director synchronization of sound and video within each shot. The crew member responsible for the design, look Construction Coordinator and feel of a film's set. Includes props, furniture, sets, Also known as the construction manager, this person etc. Reports to the production designer. supervises and manages the physical construction of Assistant Director (A.D.) sets and reports to the art director and production Carries out the director’s instructions and runs the set. designer. The first A.D. is responsible for preparing the Dailies production schedule and script breakdown, making The rough shots viewed immediately after shooting sure shooting stays on schedule and on budget. The each day by the director, along with the second A.D. is responsible for distributing information cinematographer or editor. Used to help ensure and cast notifications, keeping track of hours worked proper coverage and the quality of the shots gathered. by cast and crew, management of extras, signing Director actors in and out and preparing call sheets. The The person in charge of the overall cinematic vision of second A.D. is also in charge of the production the film and the performance of the actors. -

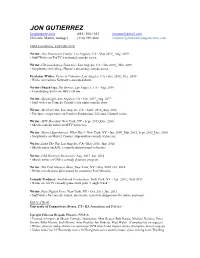

JON GUTIERREZ Jongutierrez.Com (845) 300-1683 [email protected] Christine Martin, Manager (310) 919-4661 [email protected]

JON GUTIERREZ Jongutierrez.com (845) 300-1683 [email protected] Christine Martin, manager (310) 919-4661 [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Writer, This Functional Family, Los Angeles, CA • May 2019_ Aug. 2019 • Staff Writer on TruTV’s animated comedy series. Writer, Ultramechatron Team Go!, Los Angeles, CA • Jan. 2019_ Mar. 2019 • Scriptwriter on College Humor’s streaming comedy series. Freelance Writer, Victor & Valentino, Los Angeles, CA • Oct. 2018_ Dec. 2018 • Writer on Cartoon Network’s animated show. Writer (Punch Up), The Detour, Los Angeles, CA • Aug. 2018 • Contributing writer on TBS’s sitcom. Writer, @midnight, Los Angeles, CA • Feb. 2017_Aug. 2017 • Staff writer on Comedy Central’s late night comedy show. Writer, My Crazy Sex, Los Angeles, CA • April. 2016_Aug. 2016 • Freelance script writer on Painless Productions’ Lifetime Channel series. Writer, MTV Decoded, New York, NY • Sept. 2015_Dec. 2016 • Sketch comedy writer on MTV webseries. Writer, Marvel Superheroes: What The!?, New York, NY • Jan. 2009_May 2012, Sept. 2015_Dec. 2016 • Scriptwriter on Marvel Comics’ stop-motion comedy webseries. Writer, Land The Gig, Los Angeles, CA • May 2016_June 2016 • Sketch writer on AOL’s comedy/instructional webseries. Writer, CBS Diversity Showcase • Aug. 2015_Jan. 2016 • Sketch writer on CBS’s comedy diversity program. Writer, The Paul Mecurio Show, New York, NY • May 2014_Oct. 2014 • Writer on talk show pilot hosted by comedian Paul Mecurio. Comedy Producer, NorthSouth Productions, New York, NY • Apr. 2013_ May 2013 • Writer on TruTV comedy game show pilot “Laugh Truck.” Writer, Fuse Digital News, New York, NY • Oct. 2011_Jan. 2013 • Staff writer for comedy videos, interviews, news hits and promos for online and onair. -

Inventing Television: Transnational Networks of Co-Operation and Rivalry, 1870-1936

Inventing Television: Transnational Networks of Co-operation and Rivalry, 1870-1936 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the faculty of Life Sciences 2011 Paul Marshall Table of contents List of figures .............................................................................................................. 7 Chapter 2 .............................................................................................................. 7 Chapter 3 .............................................................................................................. 7 Chapter 4 .............................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 5 .............................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 6 .............................................................................................................. 9 List of tables ................................................................................................................ 9 Chapter 1 .............................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 2 .............................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 6 .............................................................................................................. 9 Abstract .................................................................................................................... -

The Transom Review February, 2003 Vol

the transom review February, 2003 Vol. 3/Issue 1 Edited by Sydney Lewis Gwen Macsai’s Topic About Gwen Macsai Gwen Macsai is an award winning writer and radio producer for National Public Radio. Her essays have been heard on All Things Considered, Morning Edition and Weekend Edition Saturday with Scott Simon since 1988. Macsai is also the creator of "What About Joan," starring Joan Cusack and author of "Lipshtick," a book of humorous first person essays published by HarperCollins in February of 2000. Born and bred in Chicago (south shore, Evanston), Macsai began her career at WBEZ-FM and then moved to Radio Smithsonian at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. After working for NPR for eight years she moved to Minneapolis, MN where "Lipshtick" was born, along with the first of her three children. Then, one day as she tried to wrangle her smallish-breast-turned-gigantic- snaking-fire-hose into the mouth of her newborn babe, James L. Brooks, (Producer of the Mary Tyler Moore Show, Taxi, The Simpsons and writer of Terms of Endearment, Broadcast News and As Good As It Gets), called. He had just heard one of her essays on Morning Edition and wanted to base a sitcom on her work. In 2000, "What About Joan" premiered. The National Organization for Women chose "What About Joan" as one of the top television shows of that season, based on its non- sexist depiction and empowerment of women. Macsai graduated from the University of Illinois and lives in Evanston with her husband and three children. Copyright 2003 Atlantic Public Media Transom Review – Vol. -

Writing for Instructional Television. P INSTITUTION Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 221 158 IR 010 181 AUTHOR O'Bry,an, Kenneth G. no. TITLE Writing for Instructional Television. P INSTITUTION Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-89776-0521-2 PUB DATE' 81 NOTE 157p. AVAILABLE FROM-Corporation for Public Broadcasting, 1111 16th St.," N.W., Washington, DC 20036 ($5.0,0, prepaid). EDRS PRICE MF01 Plds Postage. PC Not Available from' EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Educational Television; Group Dynamics; *Instructional Design; *Production Techniques; *Programing (Broadcast); Public Television; *Scripts; Telexiision Studios ABSTRACT Writing Considerations specific to instructional television (ITV) situations are discussed in this handbook written for the beginner, but designed to be of use to anyone creating an ITV script. Advice included in the handbook is based on information obtained from ITV wirters, literature reviews, and the author's ' personal,experience. The ITV writer's relationship to other members of a project team is discussed, as well as the role of each team member, including the project leader, instructional designer, academic consultant, researcher, producer/director, utilization - person, and writer. Specific suggestions are then made for writing and working with the project team and additional production crew members. A chapter is devoted to such specific ITV writing conventions as script format, production grammar, camera terminology, and transitions between shots. Understanding production technology is the focus of a chapter which discusses lighting, sound, set design, and special effects. An in-depth look at choice of form--narrative, dramatic, documentary, magazine, ortdrama--is provided, followed by advice and guidelines for dealing with such factors as the target audience, budget and caktitig, treatment, visualization, and revisions. -

The WGC Showrunner Code Found Its Origin in the Largest Gathering Ever of Canada’S Top Showrunners

SThheowWrGuC nner Code • From WGC members to WGC members • Insights into the craft and business of showrunning in Canada WGC SHOWRUNNER CODE The WGC Showrunner Code found its origin in the largest gathering ever of Canada’s top showrunners. In 2009, the WGC invited more than thirty member showrunners – those working on one-hour dramas, half-hour dramas and half-hour comedies, for kids and adults, in both extended run and limited run – to share their experiences of and insights into the craft and business behind the role of the showrunner. A common thread emerged: to create a good show, a production needs the formative hand of a practiced showrunner, and that writer needs to see the process through from story- breaking in the writers’ room to fine cut in the edit suite. The showrunner’s world is fraught with challenges – not the least of which is the resistance some producers bring to even acknowledging that “showrunner” is a position that exists, let alone one that should be occupied first and foremost by a writer. Writers and agents came to the WGC seeking some assistance in establishing a standard set of terms for showrunners to negotiate. The WGC Showrunner Code establishes guidelines for individual negotiations. (Note: The WGC Showrunner Code was updated in January 2013 to reflect the showrunners’ increasing involvement in the creation of convergent digital content – see page 11.) The WGC Showrunner Code sets out the conditions under which the showrunner is best positioned to ensure he or she can realize their vision and deliver the best show possible.