MRI Essentials Demo Shoulder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management of the First-Time Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Dislocation

CONCISE REVIEW CiSE Clinics in Shoulder and Elbow Clinics in Shoulder and Elbow Vol. 21, No. 3, September, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5397/cise.2018.21.3.169 Management of the First-time Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Dislocation Sung Il Wang Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Research Insitute for Endocrine Sciences and Research Insitute of Clinical Medicine of Chonbuk National University–Biomedical Research Insitute of Chonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, Korea Traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder is one of the most common directions of instability following a traumatic event. Although the incidence of shoulder dislocation is similar between young and elderly patients, most studies have traditionally focused on young pa- tients due to relatively high rates of recurrent dislocations in this population. However, shoulder dislocations in older patients also require careful evaluation and treatment selection because they can lead to persistent pain and disability due to rotator cuff tears and nerve injuries. This article provides an overview of the nature and pathology of acute primary anterior shoulder dislocation, widely accepted management modalities, and differences in treatment for young and elderly patients. (Clin Shoulder Elbow 2018;21(3):169-175) Key Words: Glenohumeral joint; Shoulder dislocation; Treatment Introduction the shoulder will invariably be damaged, rendering the joint un- stable. The glenohumeral joint has the greatest range of motion There are controversies over the best treatment for patients among all joints in the human body. To achieve increased with first-time anterior shoulder dislocation. Assessment of risk mobility, joint stability is sacrificed, making shoulder joint sus- factors for recurrence is essential when deciding on the treat- ceptible to dislocation. -

The Spectrum of Lesions and Clinical Results of Arthroscopic Stabilization of Acute Anterior Shoulder Instability

DOI 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.3.421 Original Article pISSN: 0513-5796, eISSN: 1976-2437 Yonsei Med J 51(3): 421-426, 2010 The Spectrum of Lesions and Clinical Results of Arthroscopic Stabilization of Acute Anterior Shoulder Instability Doo Sup Kim, Yeo Seung Yoon, and Sung Min Kwon Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea. Received: June 11, 2009 Purpose: The purpose of this study is to investigate and analyze accom-panying Revised: August 1, 2009 lesions including injury types of anteroinferior labrum lesion in young and active Accepted: August 6, 2009 patients who suffered traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation for the first time. Corresponding author: Dr. Doo Sup Kim, Meterials and Methods: The study used magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, to 40 patients with acute anterior shoulder dislocation from April 2004 to April Wonju College of Medicine, Yonsei University, 2008, and of those, 36 with abnormal MRA finding were treated with arthroscopy. 162 Ilsan-dong, Wonju 220-701, Korea. Results: There was a total of 25 cases of anteroinferior glenoid labrum lesions. A Tel: 82-33-741-1357, Fax: 82-33-746-7326 superior labrum anterior-posterior lesion (SLAP) lesion was observed in 8 cases. E-mail: [email protected] For bony lesions, 22 cases of Hill-sachs lesions, 4 cases of lesions in greater ∙The authors have no financial conflicts of tuberosity fracture of humerus, and 4 cases of loose body were found. For lesions interest. involving rotator cuff, partial articular side rupture was found in 2 cases and 2 cases were found to have a complete rupture. -

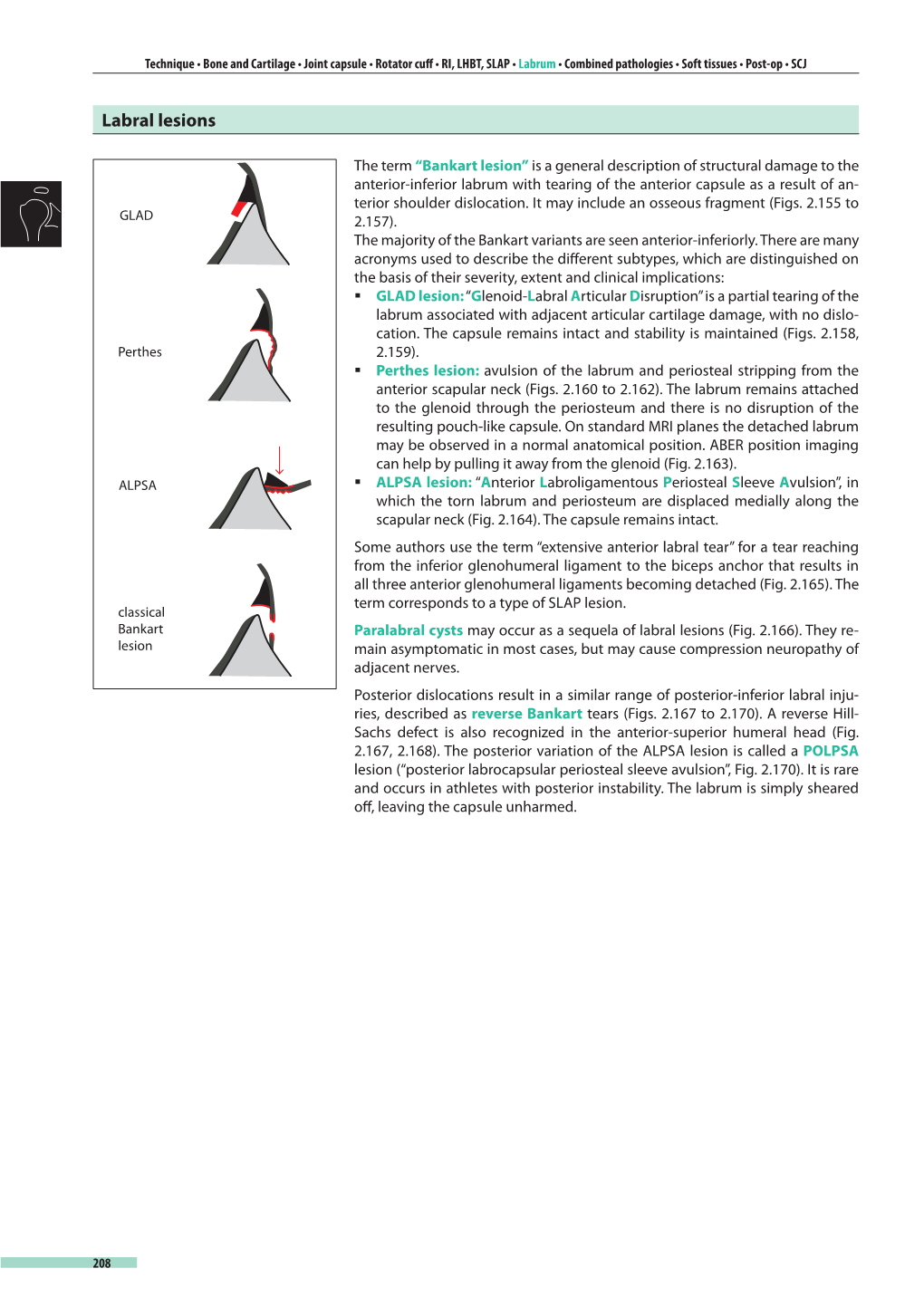

Imaging of the Shoulder Bankart Lesion and Its Variants

REVIEW ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3126/njr.v9i1.24816 Imaging of the Shoulder Bankart Lesion and its Variants Leow KS1, Low SF2, PehWCG1 1Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Yishun Central, Singapore, Republic of Singapore 2Department of Radiology, Kuala Lumpur Sports Medicine Centre, Jalan Dungun, Bukit Damansara, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Received: March 08, 2019 Accepted: April 15, 2019 Published: June 30, 2019 Cite this paper: Leow KS, Low SF, PehWCG. Imaging of the Shoulder Bankart Lesion and its Variants. Nepalese Journal of Radiology 2019;9(13):33-39. https://doi.org/10.3126/njr.v9i1.24816 ABSTRACT The glenoid labrum is an important soft tissue structure that provides stability to the shoulder joint. When the labrum is injured, affected patients may present with chronic shoulder instability and future recurrent dislocation. The Bankart lesion is the most common labral injury, and is often accompanied by a Hill-Sachs lesion of the humerus. Various imaging techniques are available for detection of the Bankart lesion and its variants, such as anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion and Perthes lesion. Direct magnetic resonance (MR) arthrography is currently the imaging modality of choice for evaluation of the various types of labral tears. As normal anatomical variants of glenoid labrum are not uncommonly encountered, familiarity with appearances of this potential pitfall helps avoid misdiagnosis. Key words: Anterior Labroligamentous Periosteal Sleeve Avulsion, Glenohumeral Joint Dislocation, Hill-Sachs Lesion, MR Arthrography, Perthes Lesion, Shoulder Dislocation INTRODUCTION The shoulder joint is one of the more commonly injured joints in the body, with its inherently large range of mobility predisposing it to risk of dislocation and development of chronic instability. -

Anterior Glenohumeral Instability: Classification of Pathologies of Anteroinferior Labroligamentous Structures Using MR Arthrography

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Advances in Orthopedics Volume 2013, Article ID 473194, 4 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/473194 Clinical Study Anterior Glenohumeral Instability: Classification of Pathologies of Anteroinferior Labroligamentous Structures Using MR Arthrography Serhat Mutlu,1 Mahir MahJroLullari,2 Olcay Güler,3 Bekir Yavuz Uçar,4 Harun Mutlu,5 Güner Sönmez,6 and Hakan Mutlu6 1 Kanuni Sultan Suleyman Education and Research Hospital, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Istanbul, Turkey 2 Istanbul Medipol University, Istanbul, Turkey 3 Nisa Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey 4 Dicle University, Diyarbakır, Turkey 5 Taksim Education and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey 6 Gulhane¨ Military Medical Academy Education Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey Correspondence should be addressed to Serhat Mutlu; [email protected] Received 24 June 2013; Accepted 13 September 2013 Academic Editor: Panagiotis Korovessis Copyright © 2013 Serhat Mutlu et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. We examined labroligamentous structures in unstable anteroinferior glenohumeral joints using MR arthrography (MRA) to demonstrate that not all instabilities are Bankart lesions. We aimed to show that other surgical protocols besides classic Bankart repair are appropriate for labroligamentous lesions. The study included 35 patients (33 males and 2 females; mean age: 30.2; range: 18 to 57 years). MRA was performed in all patients. The lesions underlying patients’ instability such as Bankart, anterior labral periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA), and Perthes lesions were diagnosed by two radiologists. MRA yielded 16 diagnoses of Bankart lesions, 5 of ALPSA lesions, and 14 of Perthes lesions. -

FNB MOCK TEST 3 Answers & Explanations

FNB MOCK TEST 3 Answers & Explanations Q. 1 What is true about arthritic hip joint? A. The abductor lever arm is lengthened B. the ratio of the lever arm of the body weight to that of the abductors is increased C. The body weight lever arm is lengthened D. The abductor lever arm remains unchanged The abductor lever arm is shortened in arthritis and other hip disorders in which part or all of the head is lost or the neck is shortened. In an arthritic hip, although the length of the body weight lever arm does not change the ratio of the lever arm of the body weight to that of the abductors may be 4 : 1. The lengths of the two lever arms can be surgically changed to make their ratio approach 1 : 1. Theoretically, this reduces the total load on the hip by 30%. Answer: B Q. 2 After total hip arthroplasty which factor will cause more stress shielding in the proximal femur around the stem? A. Stem of low modulus of elasticity B. Titanium stem compared to Cobalt-Chromium (COCR) stem C. Cylindrical distal fitting stem compared to tapered stem D. Small diameter stem Stress transfer to the femur is desirable because it provides a physiologic stimulus for maintaining bone mass and preventing disuse osteoporosis. Factors affecting stress shielding are: -Modulus of elasticity: A decrease in the modulus of elasticity of a stem decreases the stress in the stem and increases stresses to the surrounding bone. This is true of stems made of metals with a lower modulus of elasticity, such as a titanium alloy, if the cross sectional diameter is relatively small. -

Free Papers Time: 08:00 - 10:00 Room: 01

Date: 2017-11-30 Session: Upper Limb Trauma Free Papers Time: 08:00 - 10:00 Room: 01. Auditorium II Abstract no.: 48755 FRACTURE BOTH BONE FOREARM IN ADULTS: MANAGEMENT BY NAILING COMPARED WITH PLATING Amiya BERA Murshidabad Medical College & Hospitals, Berhampore (INDIA) Out of 500 cases of nailing both bone fracture forearm in adults, we studied 200 cases and compared it with 110 cases of plating both bone fracture forearm in a retrospective study – to evaluate usefulness of nailing in day-to-day practice. Clinical, radiological, objective and subjective assessments were done. Earlier open nailing changed to closed nailing with availability of c-arm, has improved results, and in spite of anatomical alteration biological nailing has several advantages with less complications compared to plating. Nailing, a cheap option still has a role in third world countries with poor economic condition, while plating is gold standard. Date: 2017-11-30 Session: Upper Limb Trauma Free Papers Time: 08:00 - 10:00 Room: 01. Auditorium II Abstract no.: 48777 UPPER LIMB GUNSHOT INJURIES: THE CAPE TOWN EXPERIENCE Esmee ENGELMANN1, Sithombo MAQUNGO2, Stephen ROCHE2, M HELD2 1Groote Schuur Hospital, Amsterdam (NETHERLANDS), 2Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town (SOUTH AFRICA) Background: Upper extremity gunshot fractures are generally treated conservatively or surgically using open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), intramedullary nails (IM) or external fixators. However, there is no gold standard for the management of these complex, multi-fragmentary upper extremity fractures. Aim: To describe and identify the injury patterns, management, complications and associated risk factors for upper extremity gunshot fractures. Methods: Data of patients with upper extremity gunshot injuries that presented to a Level I Trauma Unit in Cape Town, South Africa was collected prospectively over a ten-month period from June 2014 to April 2015. -

Project Overview

Sports Related Imaging of the Shoulder Robert R Bleakney Joint Department of Medical Imaging University Health Network, Mount Sinai and Women’s College Hospitals Shoulder: Glenohumeral Joint Greatest ROM of any joint in the body Tremendously versatile & mobile Mobility– at expense of stability Normal function dependent upon • balance between static and dynamic constraints of the joint Injury that disturbs balance • Biomechanical changes • Instability Clinically manifest: Poorly localized pain/weakness Mechanical symptoms • popping, catching, grinding • GHJ dislocation Stabilizing Restraints: Shoulder Active (extrinsic) • Rotator cuff and other musculature Passive (intrinsic) • Osseous geometry • Labrocapsular complex Labrum, Capsule & Glenohumeral ligaments Labrum Fibrocartilagenous tissue Stabilizer - GH joint Encircles glenoid Increases depth/volume glenoid 50% Pressure seal Primary attachment • LH Biceps, GH ligaments MR Imaging Fibrocartilagenous labrum Usually of low signal on MR sequences Best evaluated • MR arthrography Glenohumeral Ligaments Critical passive stabilizers GHJ Condensations joint capsule Superior GHL Middle GHL • Most variable in size • Thickened or absent Inferior GHL • Ant & Post bands, Ax recess Inferior GHL Lax – neutral position Taught – abduction “Hammock” humeral head Major passive stabilizer GHJ Stability Anterior joint capsule Etiology Shoulder Instability Traumatic Microtraumatic Atraumatic Unidirectional Multidirectional Less laxity More laxity Rationale MR Imaging - Define anatomic lesion(s) - Cause instability, -

Emory Radiology and Orthopaedics Surgery

Arthroscopy / MRI Correlation Conference Department of Radiology, Section of MSK Imaging Department of Orthopedic Surgery 7/19/16 Case 1: 29 YOM with recurrent shoulder dislocations Glenoid cartilage Axial T1FS MR arthrogram shows tear Glenoid of the anterior inferior labrum which Sagittal oblique T1FS MR cartilage remains attached to torn and medially arthrogram shows tear of the stripped periosteum of the scapula anterior inferior labrum as part (anterior labroligamentous periosteal of the ALPSA lesion. This is the sleeve avulsion AKA ALPSA lesion) same view as seen on the right during arthroscopy. Probe pulls back tear further to show the periosteum is medially stripped Case 1: 29 YOM with recurrent shoulder dislocations Repaired anterior inferior labroligamentous complex. Sutures hold these structures down at their anatomic locations. Glenoid cartilage Case 1: 29 YOM with recurrent shoulder dislocations Humeral head cartilage Humeral head Glenoid Glenoid cartilage Axial T1FS MR arthrogram shows fraying of the direct posterior labrum Arthroscopy shows fraying of the Same MR as on the left but zoomed in direct posterior labrum (which was to match the field of view from debrided at the time of surgery) arthroscopy Case 2: 21YOM with pain at the lateral joint line Lateral femoral condyle Lateral femoral condyle cartilage cartilage Lateral tibial Lateral tibial plateau cartilage plateau cartilage Lateral meniscus tear (blurry image Lateral meniscus tear debrided Coronal PDFS MR shows a complex without video to show how probe down to clean margins tear of the lateral meniscus pulls apart tear, sorry!) Medial femoral condyle cartilage Medial tibial plateau cartilage Intact ACL in the notch Intact medial meniscus Case 3: 18 YOM with medial knee pain found to have large unstable OCL in MFC (top left). -

Shoulder Acronyms Explained

CCSU SPORTS MEDICINE SYMPOSIUM 2017 ROBERT S. WASKOWITZ, MD SPORTS MEDICINE & ORTHOPEDIC SURGERY ORTHOPEDIC ASSOCIATES OF HARTFORD DISCLAIMER . No financial relationship or compensation from any company or corporation . No off-label use of any product or device 1 CCSU SPORTS MEDICINE SYMPOSIUM 2017 Objectives . Enhance understanding of shoulder instability . Comprehend specific shoulder acronyms . Understand evolving techniques for shoulder stabilization Perspective . Just when you think you understand something… …you don’t Curiosity . We want to know… …Vexing when you don’t know the answer 2 CCSU SPORTS MEDICINE SYMPOSIUM 2017 Motivation . Desire to understand a concept in order to enact a positive change… …staying one step ahead “Understanding” . Evolution of a compiled knowledge base pioneered by those who established the foundation . Progress is marked by those pushing the conceptual templates to the next level . Success is measured by actual proof, tempered by tangible failure The Shoulder . Delicate balance between stability and mobility 3 CCSU SPORTS MEDICINE SYMPOSIUM 2017 The Shoulder simple complex . Humeral head . Static restraints Labrum Ligament . Glenoid SGHL, MGHL, IGHL . Dynamic restraints . Acromial arch Rotator cuff . Concavity- compression concept . Acromio-clavicular architecture . Motion link GH 60%, ST 40% When things go right . Coordinated interaction of mechanical components with subtle but precise neuromuscular function When things go wrong . Disruption of the chain leading to dysfunction and compromise Acute traumatic Chronic repetition 4 CCSU SPORTS MEDICINE SYMPOSIUM 2017 Perspective . Learn from the pioneers by standing on their “shoulders” Experience is something you get just after you need it… Historical Perspective . Edwin Smith Papyrus Ancient Egypt c. 1600 BC Oldest surgical document Anatomic observations and examination, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of 48 types of medical problems Possibly transcribed from earlier work by Imhotep c. -

Shoulder Joint Instability Evaluation by CT Arthrography and MR Arthrography

ARTICLE IN PRESS The Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine (2016) xxx, xxx–xxx Egyptian Society of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine The Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine www.elsevier.com/locate/ejrnm www.sciencedirect.com Shoulder joint instability evaluation by CT arthrography and MR arthrography Amany Elkharbotly Radiology Department, Benha Faculty of Medicine, Benha University, Egypt Received 6 November 2015; accepted 31 March 2016 Available online xxxx KEYWORD Abstract Background and introduction: Our work aimed to compare and evaluate CT arthrogra- Shoulder instability; phy (CTA) and MR arthrography (MRA) techniques in diagnosing glenohumeral joint instabilities, MRA; also help the clinician to choose the ideal diagnostic modalities CTA & MRA either separately or CTA combined to reach the early and accurate diagnosis of glenohumeral joint instability. Patient and methods: The study included 96 patients: 72 males, 24 females. Their age ranged from 14 to 51 years (mean = 33), complaining of shoulder dislocation whether traumatic or non- traumatic with glenohumeral instability. For every patient, intra-articular contrast injection was done followed by CT and MRI arthrogra- phy (CTA & MRA). Results: Preliminary results showed the role of CTA & MRA in diagnosing the causes of instabil- ity. Correlation between CTA and MRA may have a role in more accurate diagnosis of gleno- humeral instability. Conclusion: The combination of CT arthrography and MR arthrography is a promisable one in defining the type of instability. Ó 2016 The Egyptian Society of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/). -

MRI of the Head & Spine 2017

34 th Annual MRI Of the Head & Spine 2017: National Symposium Wednesday, April 5, 2017 The Venetian® | The Palazzo® • Las Vegas, Nevada Educational Symposia TABLE OF CONTENTS Wednesday, April 5, 2017 Imaging the Brachial and Lumbar-Sacral Plexus (Wende N. Gibbs, M.D.) ...................................................................... 355 MRI of the Cervical Spine - MSK Perspective (William B. Morrison, M.D.) ..................................................................... 369 Rheumatoid Arthritis and Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies (Jeffrey J. Peterson, M.D.) ............................................... 385 MRI of the Foot and Ankle (Mark H. Awh, M.D.) .......................................................................................................... 409 Experiences/Update in Sports MRI of the Shoulder (Charles P. Ho, M.D., Ph.D.) ........................................................... 445 MRI of the Shoulder: Beyond the Cuff (Mark H. Awh, M.D.) ......................................................................................... 461 SAVE THE DATES - 2018 Spring Symposia 355 356 Objectives Imaging the Brachial and • Describe imaging features and options for the brachial and lumbosacral Lumbosacral Plexus plexus and peripheral nerves • Review relevant plexus and regional anatomy Wende N Gibbs, MD • Discuss indications for imaging Assistant Professor of Radiology University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine • Evaluate cases of the most commonly encountered pathologies Plexus and peripheral nerve -

This Article Was Published in an Elsevier Journal. the Attached Copy

This article was published in an Elsevier journal. The attached copy is furnished to the author for non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the author’s institution, sharing with colleagues and providing to institution administration. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy A Comparison of the Spectrum of Intra-articular Lesions in Acute and Chronic Anterior Shoulder Instability Christos K. Yiannakopoulos, M.D., Elias Mataragas, M.D., and Emmanuel Antonogiannakis, M.D. Purpose: The purpose of the study was to compare the incidence of secondary intra-articular shoulder lesions in patients with acute and chronic anterior shoulder instability. The occurrence of glenoid shape alterations (inverted pear glenoid) in recurrent instability was especially examined. Methods: Data for all arthroscopically ascertained intra-articular shoulder lesions in a series of 127 patients with acute and chronic traumatic anterior instability were recorded. Results: Hemarthrosis was evident in all patients with acute dislocation and in 7 patients with chronic laxity who underwent surgery shortly after a dislocation episode. In both groups the presence of a chondral or osteochondral Hill-Sachs lesion was noted in 112 patients (88.1%), a Bankart lesion was noted in 106 patients (83.46%), an anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA) lesion was noted in 13 patients (10.23%), a SLAP lesion was noted in 26 patients (20.47%), a humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesion was noted in 2 acutely dislocated shoulders (1.57%), and capsular laxity was noted in 33 patients (25.98%).