Toccata Classics TOCC 0047 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Spring Festival Focuses on Aging and Dying in Cather's Fiction

2004 Spring Festival Focuses on Aging and Dying in Cather’s Fiction Although a few may have blanched at the prospect Norma Ross Walter Scholarship winner and scholarly papers of discussing "aging" and "dying" at the 49~ annual Spring presented by Baylor University graduate students. The paper Festival in Red Cloud, there is no record of this reaction. Most sessions were followed by a lively roundtable discussion came through the experience "inspired" and "uplifted." At least featuring students from Baylor and Fort Hays State University as that was the general response of participants throughout the well as the Norma Ross Walter high school student. Mary Ryder two-day event. This same positive reaction was apparent on from South Dakota State University served as moderator. the evaluations and response forms submitted throughout the Concurrent with the Friday afternoon Auditorium events conference. was an intergenerational program focusing on children’s activities In "Old Mrs Harris" Cather sees aging and dying and storytelling. Red Cloud Elementary teacher Suzi Schulz led as a "long road that leads through things unguessed at and the group with the help of a number of local volunteers. unforeseeable," but participants found that somehow Cather Late Friday afternoon, participants were treated to a is able to make this inevitable journey an acceptable and even preview segment of the PBS biography of Willa Cather to be tranquil part of the scheme of aired on the American Masters life for her characters in the Series next year. Co-producers featured text, Obscure Destinies. Joel Geyer and Christine Lesiak Central to the Festival presented the segment and was the keynote address discussed the 90-minute film. -

Elements of Traditional Folk Music and Serialism in the Piano Music of Cornel Țăranu

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music Music, School of 12-2013 ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU Cristina Vlad University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Commons Vlad, Cristina, "ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU" (2013). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 65. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU by Cristina Ana Vlad A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Mark Clinton Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2013 ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU Cristina Ana Vlad, DMA University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Mark Clinton The socio-political environment in the aftermath of World War II has greatly influenced Romanian music. During the Communist era, the government imposed regulations on musical composition dictating that music should be accessible to all members of society. -

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

Bucharest Booklet

Contact: Website: www.eadsociety.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/EADSociety Twitter (@EADSociety): www.twitter.com/EADSociety Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/eadsociety/ Google+: www.google.com/+EADSociety LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/euro-atlantic- diplomacy-society YouTube: www.youtube.com/c/Eadsociety Contents History of Romania ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 What you can visit in Bucharest ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Where to Eat or Drink ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Night life in Bucharest ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Travel in Romania ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….....10 Other recommendations …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….11 BUCHAREST, ROMANIA MIDDLE AGES MODERN ERA Unlike plenty other European capitals, Bucharest does not boast of a For several centuries after the reign of Vlad the Impaler, millenniums-long history. The first historical reference to this city under Bucharest, irrespective of its constantly increasing the name of Bucharest dates back to the Middle Ages, in 1459. chiefdom on the political scene of Wallachia, did undergo The story goes, however, that Bucharest was founded several centuries the Ottoman rule (it was a vassal of the Empire), the earlier, by a controversial and rather legendary character named Bucur Russian occupation, as well as short intermittent periods of (from where the name of the city is said to derive). What is certain is the Hapsburg -

Chirurgia 1 Mad C 4'2006 A.Qxd

History of Medicine Chirurgia (2020) 115: 7-11 No. 1, January - February Copyright© Celsius http://dx.doi.org/10.21614/chirurgia.115.1.7 The Man Behind Roux-En-Y Anastomosis Carmen Naum1, Rodica Bîrlã1,2, Cristina Gândea1,2, Elena Vasiliu2, Silviu Constantinoiu1,2 1Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania 2General and Esophageal Surgery Department, Center of Excellence in Esophageal Surgery, Saint Mary Clinical Hospital, Bucharest, Romania Corresponding author: Rezumat Rodica Birla, MD General and Esophageal Surgery Department, Center of Excellence in Esophageal Surgery, Sf. Maria César Roux (1857–1934) s-a născut în satul Mont-la-Ville din Clinical Hospital, Bucharest, Romania cantonul Vaud, Elveţia şi a fost cel de-al cincilea fiu, dintre cei 11, E-mail: [email protected] ai unui inspector şcolar. A studiat medicina la Universitatea din Berna şi i-a avut printre profesori pe Thomas Langhans în patologie şi pe Thomas Kocher în chirurgie. Roux, la fel ca mulţi chirurgi din acea perioadă a practicat chirurgia ginecologică, ortopedică, generală, toracică şi endocrină, dar a devenit celebru în chirurgia viscerală. El a dominat toate domeniile chirurgicale şi a influenţat chirurgia cu spiritul său inovator, dar contribuţia sa cea mai mare a fost anastomoza Roux-în-Y. Fiind un chirurg meticulos, dar care în acelaşi timp, opera repede, o persoană muncitoare, dedicată pacienţilor şi studenţilor săi, el şi-a găsit un loc în istoria medicinei. A murit în 1934, iar moartea sa bruscă a fost un motiv de doliu naţional în Elveţia. Cuvinte cheie: Roux, César Roux, Roux-în-Y, gastroenterostomy, istoria chirurgiei Abstract César Roux (1857–1934) was born in the village of Mont-la-Ville in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland and he was the fifth son, among 11 children, of an inspector of schools. -

BRAHMS: Neue Liebeslieder Walz- Britten Records in the American Cata- Orchestra, No

midway between the granitic massive- val Orchestra, Yehudi Menuhin, cond. prefaced the work with the Corelli Con- ness of Backhaus and the wry linearity of (in the Britten and Corelli), Michael certo grosso from which the theme of Kempff, and thoroughly comparable to Tippett, cond. (in the Tippett). Tippett's work is taken. Intellectual both. ANGEL 36303. LP. $4.79. stimulation and sensuous delight are The sound is fine, if a trifle low in ANGEL S 36303. SD. $5.79. equally abundant on this lovely record. level in the stereo pressing of the Bee- B.J. thoven disc. H.G. I was astonished to discover that there was no version of the Frank Bridge Variations among the fairly numerous CHOPIN: Concerto for Piano and BRAHMS: Neue Liebeslieder Walz- Britten records in the American cata- Orchestra, No. 1, in E minor, Op. er, Op. 65 logues. This witty, polished work, com- 11; Mazurkas: No. 54, in D, Op. (Hindemith: Sonata for Piano, 4 posed in the space of a few weeks when posth.: No. 46, in C, Op. 67, No. 3; Hands Britten was twenty- three, was the first No. 49, in A minor, Op. 68, No. his pieces to bring him into in- 1-Stravinsky: Pétrouchka: Suite of the 2; No. 5, in B flat, Op. 7, No. 1 ternational limelight, when it was per- Yaltah Menuhin and Joel Ryce, piano. formed at the 1937 Salzburg Festival. Tamás Vásáry. piano: Berlin Philhar- EVEREST 6130. LP. $4.98. It won him an immediate reputation for monic Orchestra. Jerzy Semkov, cond. EVEREST 3130. -

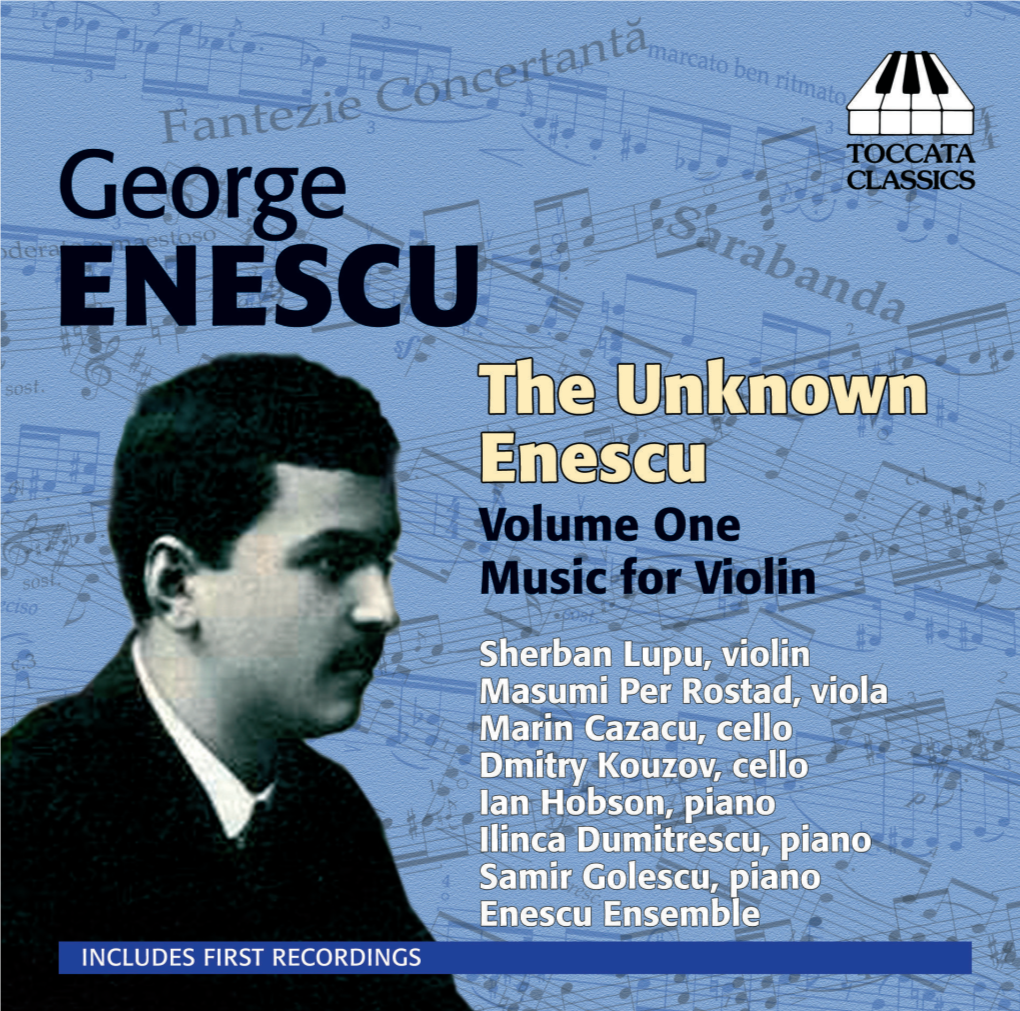

THE UNKNOWN ENESCU Volume One: Music for Violin

THE UNKNOWN ENESCU Volume One: Music for Violin 1 Aubade (1899) 3:46 17 Nocturne ‘Villa d’Avrayen’ (1931–36)* 6:11 Pastorale, Menuet triste et Nocturne (1900; arr. Lupu)** 13:38 18 Hora Unirei (1917) 1:40 2 Pastorale 3:30 3 Menuet triste 4:29 Aria and Scherzino 4 Nocturne 5:39 (c. 1898–1908; arr. Lupu)** 5:12 19 Aria 2:17 5 Sarabande (c. 1915–20)* 4:43 20 Scherzino 2:55 6 Sérénade lointaine (1903) 4:49 TT 79:40 7 Andantino malinconico (1951) 2:15 Sherban Lupu, violin – , Prelude and Gavotte (1898)* 10:21 [ 20 conductor –, – 8 Prelude 4:32 Masumi Per Rostad, viola 9 Gavotte 5:49 Marin Cazacu, cello , Airs dans le genre roumain (1926)* 7:12 Dmitry Kouzov, cello , , 10 I. Moderato (molto rubato) 2:06 Ian Hobson, piano , , , , , 11 II. Allegro giusto 1:34 Ilinca Dumitrescu, piano , 12 III. Andante 2:00 Samir Golescu, piano , 13 IV. Andante giocoso 1:32 Enescu Ensemble of the University of Illinois –, – 20 14 Légende (1891) 4:21 , , , , , , DDD 15 Sérénade en sourdine (c. 1915–20) 4:21 –, –, –, , – 20 ADD 16 Fantaisie concertante *FIRST RECORDING (1932; arr. Lupu)* 11:04 **FIRST RECORDING IN THIS VERSION 16 TOCC 0047 Enescu Vol 1.indd 1 14/06/2012 16:36 THE UNKNOWN ENESCU VOLUME ONE: MUSIC FOR VIOLIN by Malcolm MacDonald Pastorale, Menuet triste et Nocturne, Sarabande, Sérénade lointaine, Andantino malinconico, Airs dans le genre roumain, Fantaisie concertante and Aria and Scherzino recorded in the ‘Mihail Jora’ Pablo Casals called George Enescu ‘the greatest musical phenomenon since Mozart’.1 As Concert Hall, Radio Broadcasting House, Romanian Radio, Bucharest, 5–7 June 2005 a composer, he was best known for a few early, colourfully ‘nationalist’ scores such as the Recording engineer: Viorel Ioachimescu Romanian Rhapsodies. -

Surf Book Surfing Legends Channel Photographics

0-9744029-4-X LLC Channel Photographics Photography/Sports & Recreation $65.00/Cloth 256 Pages 200 Full-Color and B&W Photographs 9 x 11 November Channel Photographics LLC Surfing Legends Surf Book By Michael Halsband and Joel Tudor hotographic odyssey of the remarkable charac- Michael Halsband is a leading studio photographer of ters who color surfing's past and present. music, fashion and celebrities, including Sofia Coppola, Hunter S. Thompson, Keith Haring, Iggy P Pop, Al Pacino, Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat and This portrait, accompanied by fascinating stories, Lawrence Fishburne; and was official photographer chronicles a pantheon of living surf maestros from the for the Rolling Stones' Tattoo You tour. historic and contemporary surfing communities: ✯ surf champions Joel Tudor is one of surfing's most influential, original ✯ master board builders and entertaining personalities. ✯ underground cult figures MARKETING: ✯ Led by a popular surf personality and a legendary author events in Los Angeles and New York celebrity photographer, this is a photographic surf ✯ features and reviews in photography, surf, mens' and journey from La Jolla to the North Shore; from Malibu specialty sports magazines to Oregon; and from Noosa Heads to the Windan Sea. 1 SCB DISTRIBUTORS Clarity Press 0-932863-42-6 Current Events/Political Science $14.95/Paper 180 Pages 52 x 82 November Clarity Press Go-To Conspiracy Guide The Intelligence Files Today's Secrets, Tomorrow's Scandals By Olivier Schmidt “If one hopes to make sense of events in the murky world of intelligence and international security, one has to consult multiple sources originating from diverse perspectives. -

Razing of Romania's Past.Pdf

REPORT Ttf F1 *t 'A. Í M A onp DlNU C GlURESCU THE RAZING OF ROMANIA'S PAST The Razing of Romania's Past was sponsored by the Kress Foundation European Preservation Program of the World Monuments Fund; it was published by USACOMOS. The World Monuments Fund is a U.S. nonprofit organization based in New York City whose purpose is to preserve the cultural heritage of mankind through administration of field restora tion programs, technical studies, advocacy and public education worldwide. World Monuments Fund, 174 East 80th Street, New York, N.Y. 10021. (212) 517-9367. The Samuel H. Kress Foundation is a U.S. private foundation based in New York City which concentrates its resources on the support of education and training in art history, advanced training in conservation and historic preservation in Western Europe. The Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 174 East 80th Street, N.Y. 10021. (212) 861-4993. The United States Committee of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (USACOMOS) is one of 60 national committees of ICOMOS forming a worldwide alliance for the study and conservation of historic buildings, districts and sites. It is an international, nongovernmental institution which serves as the focus of international cultural resources ex change in the United States. US/ICOMOS, 1600 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C., 20006. (202) 842-1866. The text and materials assembled by Dinu C. Giurescu reflect the views of the author as sup ported by his independent research. Book design by DR Pollard and Associates, Inc. Jacket design by John T. Engeman. Printed by J.D. -

The Career and Legacy of Hornist Joseph Eger: His Solo

THE CAREER AND LEGACY OF HORNIST JOSEPH EGER: HIS SOLO CAREER, RECORDINGS, AND ARRANGEMENTS Kathleen S. Pritchett, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: William Scharnberg, Major Professor Gene Cho, Committee Member Keith Johnson, Committee Member Terri Sundberg, Chair of the Instrumental Studies Division Graham Phillips, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the School of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Pritchett, Kathleen S., The Career and Legacy of Hornist Joseph Eger: His Solo Career, Recordings, and Arrangements. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2008, 43 pp., 3 tables, references, 28 titles. This study documents the career of Joseph Eger (b. 1920), who had a short but remarkable playing career in the 1940’s, 1950’s and early 1960’s. Eger toured the United States and Britain as a soloist with his own group, even trading tours with the legendary British hornist, Dennis Brain. He recorded a brilliant solo album, transcribed or arranged several solos for horn, and premiered compositions now standard in the horn repertoire. He served as Principal Horn of the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and the National Symphony. Despite his illustrious career as a hornist, many horn players today do not recognize his name. While Eger was a renowned horn soloist in the middle of the twentieth century, he all but disappeared as a hornist, refocused his career, and reemerged as a conductor, social activist, and author. -

The Spa: Business Opportunity Or a 'Dime Per Dozen' Affair?

The Spa Business opportunity or a ‘dime per dozen’ affair? Dissertation I hereby declare that this dissertation is wholly the work of Raluca Paris. Any other contributors or sources have either been referenced in the prescribed manner or are listed in the acknowledgments together with the nature and the scope of their contribution R. Paris Student at NHTV University of Applied Sciences Master program Tourism Destination Management December. 2012 The Spa: business opportunity or a ‘dime per dozen’ affair? December 13, 2012 Page left blank on purpose - 2 - Raluca Paris, 2012 @ NHTV, Breda University of Applied Science The Spa: business opportunity or a ‘dime per dozen’ affair? December 13, 2012 Motivation “If all else perished, and he remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger.” ― Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights Mankind has always had a pure connection with nature and all of its elements. No matter how far society has gone, it has always come back to the one thing which is not lost by the passing time. No matter though how much hardship we put ourselves in, without the occasional escape in an unaltered environment, the world would seem too dark. The following dissertation was written in the final phase of my master studies of Tourism Destination Management, at NHTV, Breda University of Applied Science. My research focused on how the simple process of bathing has evolved into a very profitable industry, in current times. This research was conducted in order to see if it the results can be applied to a destination which already has an existing Spa industry, but has forsaken it because of a series of unfortunate events. -

SCHIMEK During the Nineteenth Century There Was Musical Migration from Cit- Ies Such As Vienna, Milan, Venice and Prague Towards the South and East

Musical Ties of the Romanian Principalities with Austria Between 1821 and 1859 HAIGANUS PREDA-SCHIMEK During the nineteenth century there was musical migration from cit- ies such as Vienna, Milan, Venice and Prague towards the south and east. That this migration was noticeable in Serbian, Hungarian, Greek and Bulgarian cities was shown at the 17th Congress of the Interna- tional Musicology Society in Leuven, 2002.[1] A similar phenomenon took place in the Romanian world, which was not documented at this conference. The present article aims at proving that such a transfer also occurred on Romanian territory and that it was not an accidental phenomenon but part of the deeper process of political, social and cultural change suffered by the country after the second decade of the nineteenth century. A number of Austrian musicians arrived in the Romanian principalities precisely at the moment when, through a process largely supported by international politics, the Greco- Ottoman way of life was being abandoned in favor of Western habits. Politics, economy, and culture underwent a deep reform that affected mentalities, language and social practices. Foreign musicians of Aus- trian or Czech origin arrived, invited by princes or by influential local families, or even on their own in search of favorable commissions, and participated in this renewal work, particularly in its first phase (1821-1859).[2] CULTURAL CONTACTS BETWEEN THE ROMANIAN PRINCIPALITIES AND WESTERN EUROPE BETWEEN 1821 AND 1859 Musical relations between the Habsburg Empire and the Romanian principalities of Moldavia and Walachia[3] emerged against a differ- ent historical background than those in Transylvania, which had be- longed since the seventeenth century to the Habsburgs and possessed a longer tradition of Western-orientated music.