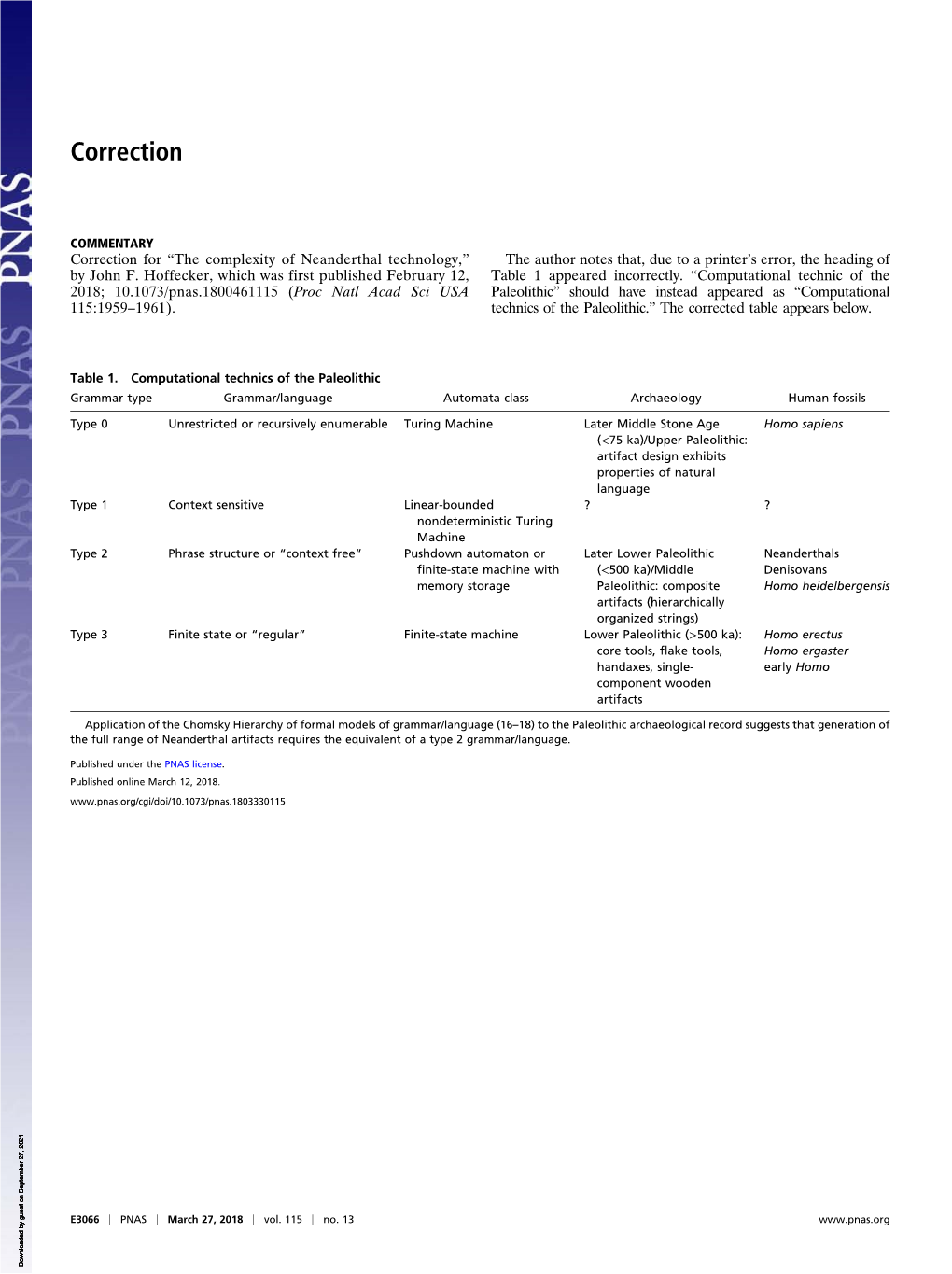

The Complexity of Neanderthal Technology,” the Author Notes That, Due to a Printer’S Error, the Heading of by John F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Middle Stone Age of East Africa and the Beginnings of Regional Identity

Journal of Worm Prehistory, Vol. 2, No. 3. 1988 The Middle Stone Age of East Africa and the Beginnings of Regional Identity J. Desmond Clark ~ The history of research into the Middle Stone Age of East Africa and the present state of knowledge of this time period is examined for the region as a whole, with special reference to paleoenvironments. The known MSA sites and occurrences are discussed region by region and attempts are made to fit them into a more precise chronological framework and to assess their cultural affinities. The conclusion is reached that the Middle Stone Age lasted for some 150,000 years but considerably more systematic and in-depth research is needed into this time period, which is now perceived as of great significance since it appears to span the time of the evolution of anatomically Modern humans in the continent, perhaps in Last Africa. KEY WORDS: Middle Stone Age; Sangoan/Lupemban; long chronology; Archaic Homo sapiens; Modern H. sapiens. • . when we eventually find the skulls of the makers of the African Mousterian they will prove to be of non-Homo sapiens type, although probably not of Neanderthal type, but merely an allied race of Homo rhodesiensis. The partial exception.., of the Stillbay culture group is therefore explicable on the grounds that Homo sapiens influence was already at work. (Leakey, 1931, p. 326) The other view is that the cradle of the Aurignacian races lies hidden somewhere in the Sahara area, probably in the south-east, and that an early wave of movement carried one branch of the stock via Somaliland and the Straits of Bab el-Mandeb into Arabia, and thence to some unknown secondary centre of distribution in Asia. -

Biface Form and Structured Behaviour in the Acheulean

Lithics 27 BIFACE FORM AND STRUCTURED BEHAVIOUR IN THE ACHEULEAN Matthew Pope 7, Kate Russel 8 and Keith Watson 9 ___________________________________________________________________________ “Homo erectus of 700,000 years ago had a geometrically accurate sense of proportion and could impose this on stone in the external world…mathematical transformations were being performed” (Gowlett 1983: 185) ABSTRACT According to some perspectives, the standardised nature of biface forms and the rule- governed nature of biface discard reflect a highly structured and static adaptation. Furthermore, i t has also been suggested that the Acheulean represents a period of over a million years in which technological and social development were in relative stasis due to social limitations. In this paper we explore the possibility that this apparently static and highly conformable adaptation may have represented a crucial pre-linguistic phase in which humans became adept at engaging with, reacting to and manipulating an early semiotic environment. We also present evidence which suggests that, in addition to symmetry, there may have been an underlying preference for the manufacture of bifaces with proportions conforming to the ‘Golden Section’. The possibility that bifacial tool form and structured archaeological signatures might have combined to produce a self-organising effect on early human land-use behaviour is explored. These behaviours, we argue, formed through simple feedback mechanisms which led to the ordered transformation of artefact scatters over time. We suggest that the apparent homogeneity of Acheulean technology might therefore signal a cognitive phase in which material culture played a semiotic role prior to the development of language. Full reference : Pope, M., Russel, K. -

Exploring Differences and Finding Connections in Archaeology And

Zambia Social Science Journal Volume 5 | Number 2 Article 6 Exploring Differences and Finding Connections in Archaeology and History Practice and Teaching in the Livingstone Museum and the University of Zambia, 1973 to 2016 Francis B. Musonda University of Zambia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/zssj Part of the African History Commons, African Studies Commons, and the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Musonda, Francis B. (2014) "Exploring Differences and Finding Connections in Archaeology and History Practice and Teaching in the Livingstone Museum and the University of Zambia, 1973 to 2016," Zambia Social Science Journal: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/zssj/vol5/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zambia Social Science Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exploring differences and finding connections in Archaeology and History practice and teaching in the Livingstone Museum and the University of Zambia, 1973 to 2016 Francis B. Musonda Department of Historical and Archaeological Studies, University of Zambia This article looks at the way archaeology and history have been practised and taught at the Livingstone Museum, Zambia and the University of Zambia in relation to each other as closely allied disciplines between 1973 and 2016. It identifies some of the areas in which they have either collaborated well, or need to do so, and those that set them apart in their common aim to study the past. -

The Use of Ochre and Painting During the Upper Paleolithic of the Swabian Jura in the Context of the Development of Ochre Use in Africa and Europe

Open Archaeology 2018; 4: 185–205 Original Study Sibylle Wolf*, Rimtautas Dapschauskas, Elizabeth Velliky, Harald Floss, Andrew W. Kandel, Nicholas J. Conard The Use of Ochre and Painting During the Upper Paleolithic of the Swabian Jura in the Context of the Development of Ochre Use in Africa and Europe https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2018-0012 Received June 8, 2017; accepted December 13, 2017 Abstract: While the earliest evidence for ochre use is very sparse, the habitual use of ochre by hominins appeared about 140,000 years ago and accompanied them ever since. Here, we present an overview of archaeological sites in southwestern Germany, which yielded remains of ochre. We focus on the artifacts belonging exclusively to anatomically modern humans who were the inhabitants of the cave sites in the Swabian Jura during the Upper Paleolithic. The painted limestones from the Magdalenian layers of Hohle Fels Cave are a particular focus. We present these artifacts in detail and argue that they represent the beginning of a tradition of painting in Central Europe. Keywords: ochre use, Middle Stone Age, Swabian Jura, Upper Paleolithic, Magdalenian painting 1 The Earliest Use of Ochre in the Homo Lineage Modern humans have three types of cone cells in the retina of the eye. These cells are a requirement for trichromatic vision and hence, a requirement for the perception of the color red. The capacity for trichromatic vision dates back about 35 million years, within our shared evolutionary lineage in the Catarrhini subdivision of the higher primates (Jacobs, 2013, 2015). Trichromatic vision may have evolved as a result of the benefits for recognizing ripe yellow, orange, and red fruits in front of a background of green foliage (Regan et al., Article note: This article is a part of Topical Issue on From Line to Colour: Social Context and Visual Communication of Prehistoric Art edited by Liliana Janik and Simon Kaner. -

Africa from MIS 6-2: the Florescence of Modern Humans

Chapter 1 Africa from MIS 6-2: The Florescence of Modern Humans Brian A. Stewart and Sacha C. Jones Abstract Africa from Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) 6-2 saw Introduction the crystallization of long-term evolutionary processes that culminated in our species’ anatomical form, behavioral The last three decades represent a watershed in our under- florescence, and global dispersion. Over this *200 kyr standing of modern human origins. In the mid-1980s, evo- period, Africa experienced environmental changes on a lutionary genetics established that the most ancient human variety of spatiotemporal scales, from the long-term disap- lineages are African (Cann 1988; Vigilant et al. 1991). Since pearance of whole deserts and forests to much higher then, steady streams of genetic, paleontological and archae- frequency, localized shifts. The archaeological, fossil, and ological insights have converged into a torrent of evidence genetic records increasingly suggest that environmental that Africa is our species’ evolutionary home, both biological variability profoundly affected early human population sizes, and behavioral. When these changes occurred, however, densities, interconnectedness, and distribution across the remains less well understood, and much less so how and why. African landscape – that is, population dynamics. At the Where within Africa modern humans and our suite of same time, recent advances in anthropological theory predict behaviors developed is also problematic. One thing seems that such paleodemographic changes were central to struc- clear: the changes that shaped our species and its behavioral turing the very records we are attempting to comprehend. repertoire were gradual, rooted deeper in the Pleistocene than The book introduced by this chapter represents a first previously imagined. -

The Relationship Between the Later Stone Age and Iron Age Cultures of Central Tanzania

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE LATER STONE AGE AND IRON AGE CULTURES OF CENTRAL TANZANIA Emanuel Thomas Kessy B.A. University of Dar es Salaam, 1991 M.Phi1. Cambridge University, 1992 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Emanuel Thomas Kessy, 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSlTY Spring 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Emanuel Thomas Kessy DEGREE: TITLE OF THESIS: The Relationship Between the Later Stone Age (LSA) and Iron Age (IA) Cultures of Central Tanzania EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chair: Dongya Yang Assistant Professor Cathy D'Andre;, Associate Professor Senior Supervisor David Burley, Professor Diane Lyons, Assistant Professor University of Calgary Ross Jamieson, Assistant Professor Internal Examiner Adria LaViolette, Associate Professor University of Virginia External Examiner Date Approved: SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project nr extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, acd to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

Barham L (2002) Backed Tools in Middle Pleistocene Central Africa

Lawrence Barham Backed tools in Middle Pleistocene central Department of Archaeology, Africa and their evolutionary significance University of Bristol, 43 Woodland Road, Bristol The fashioning of stone inserts for composite tools by blunting flakes BS8 1UU, U.K. e-mail: and blades is a technique usually associated with Late Pleistocene [email protected] modern humans. Recent reports from two sites in south central Africa (Twin Rivers and Kalambo Falls) suggest that this backed tool Received 5 December 2001 technology originated in the later Middle Pleistocene with early or Revision received ‘‘archaic’’ Homo sapiens. This paper investigates these claims critically 23 March 2002 and from the perspective of the potential mixing of Middle and Later accepted 8 July 2002 Stone Age deposits at the two sites and the possible creation of Keywords: central Africa, misleading assemblages. The review shows that backed tools form a Middle Stone Age, statistically minor, but technologically significant feature of the early Lupemban industry, backed Middle Stone Age of south central Africa. They first appear in the tools. Lupemban industry at approximately 300 ka and remain an element of the Middle Stone Age technological repertoire of the region. Comparisons are made with early backed tool assemblages of east Africa and with the much younger Howiesons Poort industry of southern Africa. The paper concludes that Lupemban tools lack the standardization of the Howiesons Poort backed pieces, but form part of a regionally distinctive and diverse assemblage of heavy and light duty tools. Some modern-like behaviours appear to have emerged by the later Middle Pleistocene in south central Africa. -

Excavations at Site C North, Kalambo Falls, Zambia: New Insights Into the Mode 2/3 Transition in South-Central Africa

Excavations at Site C North, Kalambo Falls, Zambia: New Insights into the Mode 2/3 Transition in South-Central Africa Lawrence Barham, Stephen Tooth, Geoff A.T. Duller, Andrew J. Plater & Simon Turner Abstract Résumé We report on the results of small-scale excavations at the ar- Nous présentons ici les résultats de fouilles réduites du site de chaeological site of Kalambo Falls, northern Zambia. The site Kalambo Falls, en Zambie du nord. Le site est connu depuis has long been known for its stratified succession of Stone Age longtemps pour sa stratigraphie paléolithique, surtout pour horizons, in particular those representing the late Acheulean ses niveaux attribués à l’Acheuléen supérieur (Mode 2) et au (Mode 2) and early Middle Stone Age (Mode 3). Previous Paléolithique moyen (Mode 3). Les démarches entreprises efforts to date these horizons have provided, at best, minimum précédemment pour dater ces niveaux n’ont livré que des âges radiometric ages. The absence of a firm chronology for the site radiométriques minimums. L’absence d’une bonne chronologie has limited its potential contribution to our understanding of the a limité la contribution de ce site à notre compréhension des process of technological change in the Middle Pleistocene of processus de changement technologique au cours du Pléis- south-central Africa. The aim of the excavations was to collect tocène moyen en Afrique australe. L’objectif des dernières samples for luminescence dating that bracketed archaeological fouilles était de collecter des échantillons pour la datation par horizons, and to establish the sedimentary and palaeoenviron- luminescence qui encadrent les horizons archéologiques et pour mental contexts of the deposits. -

THE OLDOWAN: Case Studies Into the Earliest Stone Age Nicholas Toth and Kathy Schick, Editors

stone age institute publication series Series Editors Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth Stone Age Institute Gosport, Indiana and Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Number 1. THE OLDOWAN: Case Studies into the Earliest Stone Age Nicholas Toth and Kathy Schick, editors Number 2. BREATHING LIFE INTO FOSSILS: Taphonomic Studies in Honor of C.K. (Bob) Brain Travis Rayne Pickering, Kathy Schick, and Nicholas Toth, editors Number 3. THE CUTTING EDGE: New Approaches to the Archaeology of Human Origins Kathy Schick, and Nicholas Toth, editors Number 4. THE HUMAN BRAIN EVOLVING: Paleoneurological Studies in Honor of Ralph L. Holloway Douglas Broadfield, Michael Yuan, Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth, editors STONE AGE INSTITUTE PUBLICATION SERIES NUMBER 1 THE OLDOWAN: Case Studies Into the Earliest Stone Age Edited by Nicholas Toth and Kathy Schick Stone Age Institute Press · www.stoneageinstitute.org 1392 W. Dittemore Road · Gosport, IN 47433 COVER PHOTOS Front, clockwise from upper left: 1) Excavation at Ain Hanech, Algeria (courtesy of Mohamed Sahnouni). 2) Kanzi, a bonobo (‘pygmy chimpanzee’) fl akes a chopper-core by hard-hammer percussion (courtesy Great Ape Trust). 3) Experimental Oldowan fl aking (Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth). 4) Scanning electron micrograph of prehistoric cut-marks from a stone tool on a mammal limb shaft fragment (Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth). 5) Kinesiological data from Oldowan fl aking (courtesy of Jesus Dapena). 6) Positron emission tomography of brain activity during Oldowan fl aking (courtesy of Dietrich Stout). 7) Experimental processing of elephant carcass with Oldowan fl akes (the animal died of natural causes). (Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth). 8) Reconstructed cranium of Australopithecus garhi. -

J. Desmond Clark 1916–2002

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES J. DESMOND CLARK 1916–2002 A Biographical Memoir by FRED WENDORF Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoirs, VOLUME 83 PUBLISHED 2003 BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. J. DESMOND CLARK April 10, 1916–February 14, 2002 BY FRED WENDORF Y ANY MEASURE J. Desmond Clark was the most influen- Btial and productive archaeologist who ever worked in Africa. More than any other individual he shaped our un- derstanding of African prehistory, and his interests and goals have structured almost all the prehistoric research now un- derway on that continent. I first met Clark in the fall of 1960, when he came to Santa Fe to give a talk on his work in Northern Rhodesia. I was then working as an American Southwestern archaeolo- gist, but Clark’s talk stimulated my interest in the archaeol- ogy of Africa. It was only two years later, in 1962, and still knowing nothing about African prehistory, that I found my- self leading the Combined Prehistoric Expedition in the salvage excavations at prehistoric sites in the Aswan reser- voir in Egypt and Sudan. It was my very good fortune that Clark was the first person I turned to in my frantic scramble to learn enough about African prehistory to do my job and not embarrass myself totally. Clark responded quickly with a packet of reprints and a long list of readings that began my African education. On many occasions since then I turned to him for guidance, and I found Desmond always to be generous with his advice and encouragement. -

Chapter 8 Micro-Hydropower Generation Planning

Chapter 8 Micro-Hydropower Generation Planning Chapter 8. Micro-Hydropower Generation Planning Chapter 8. Micro-Hydropower Generation Planning 8.1. Current Status of Micro-Hydropower Development In Zambia, there already exist some micro-hydropower plants (hereinafter referred to as “Mc-HPs”) as shown in Chapter 3. These Mc-HPs, located in a remote area far from ZESCO’s distribution lines, are operated by local cooperatives for supplying electricity to local hospitals, clinics, schools, farm, and so on. In the Rural Electrification Master Plan Study, development of Mc-HPs like that is considered to be an option to enhance rural electrification in some remote areas in Zambia. According to the estimate of some preceding studies, Zambia has a potential of hydropower generation of more than 6,000 MW and only 1,700MW out of that has been developed so far. However, not many Mc-HP projects to serve rural electrification have been discussed so far, with some exceptions like “Chitokoloki Mission” and “Zengamene” projects that REA selected for REF release in 2006 (refer to Table 3-2). This modest approach toward Mc-HPs shows a clear contrast with the case of large hydropower development to be connected to the national grid, where many projects have come up for consideration in these days, and some of them will possibly be realized, for improving the country’s supply-demand balance that has become seriously tight due to the rapid growth of domestic electricity consumption such as the recovery of mining sector. 8.2. Data Collection 8.2.1. Rainfall Data Table 8-1 shows the annual rainfall data at 39 meteorological stations that are monitored by Zambia Meteorological Department (ZMD). -

New Investigations at Kalambo Falls, Zambia: Luminescence Chronology, Site Formation, and Archaeological Significance

Journal of Human Evolution xxx (2015) 1e15 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol New investigations at Kalambo Falls, Zambia: Luminescence chronology, site formation, and archaeological significance * Geoff A.T. Duller a, , Stephen Tooth a, Lawrence Barham b, Sumiko Tsukamoto c a Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, SY23 3DB, UK b Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool, L69 3GS, UK c Leibniz Institute for Applied Geophysics, Geochronology and Isotope Hydrology, Stilleweg 2, Hannover D-30655, Germany article info abstract Article history: Fluvial deposits can provide excellent archives of early hominin activity but may be complex to interpret, Received 29 August 2014 especially without extensive geochronology. The Stone Age site of Kalambo Falls, northern Zambia, has Accepted 1 May 2015 yielded a rich artefact record from dominantly fluvial deposits, but its significance has been restricted by Available online xxx uncertainties over site formation processes and a limited chronology. Our new investigations in the centre of the Kalambo Basin have used luminescence to provide a chronology and have provided key Keywords: insights into the geomorphological and sedimentological processes involved in site formation. Excava- Fluvial deposits tions reveal a complex assemblage of channel and floodplain deposits. Single grain quartz optically Geochronology Meander stimulated luminescence (OSL) measurements provide the most accurate age estimates for the youngest South-central Africa sediments, but in older deposits the OSL signal from some grains is saturated. A different luminescence Stone Age signal from quartz, thermally transferred OSL (TT-OSL), can date these older deposits.