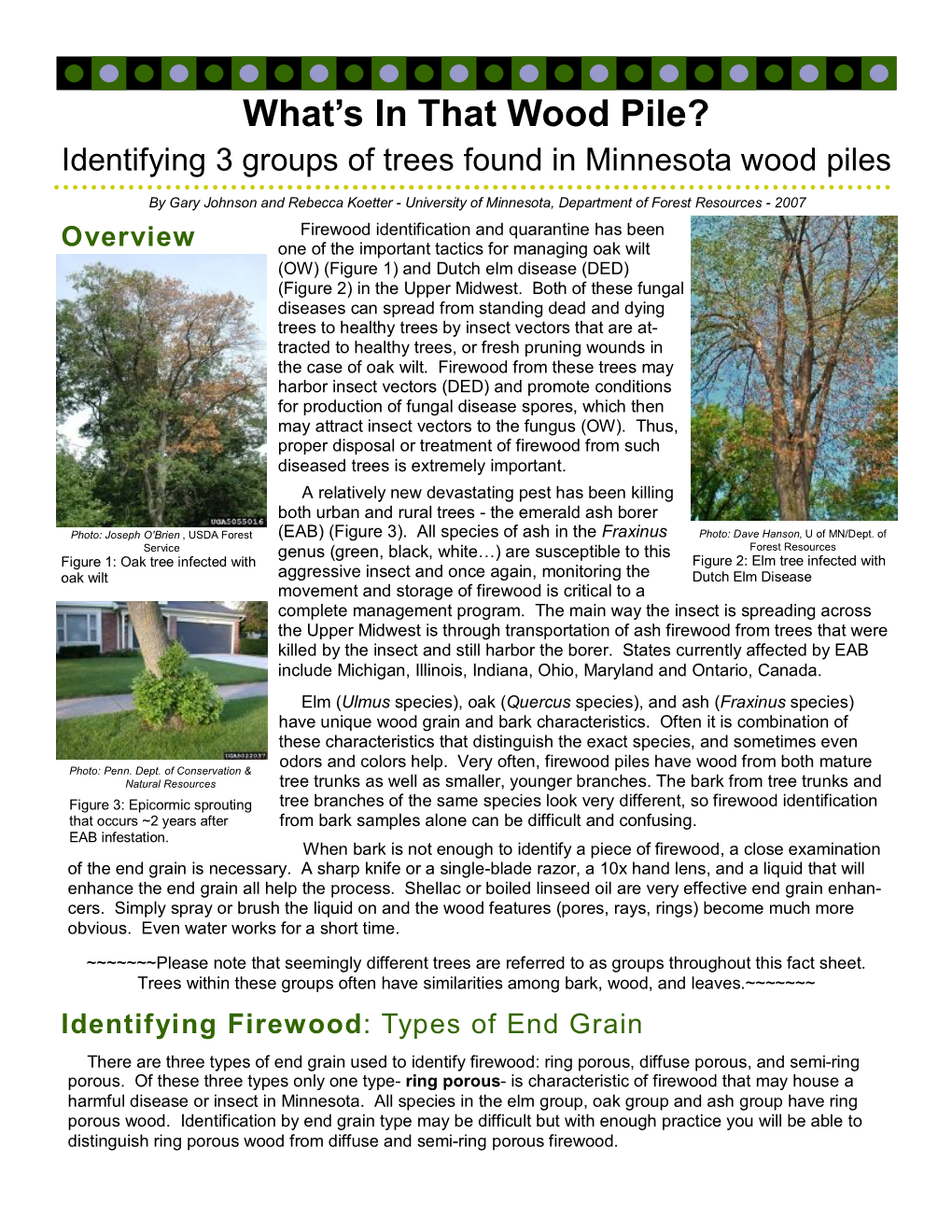

What's in That Wood Pile?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stegophora Ulmea

EuropeanBlackwell Publishing, Ltd. and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization Organisation Européenne et Méditerranéenne pour la Protection des Plantes Data sheets on quarantine pests Fiches informatives sur les organismes de quarantaine Stegophora ulmea widespread from the Great Plains to the Atlantic Ocean. Sydow Identity (1936) reported a foliar disease of Ulmus davidiana caused by Name: Stegophora ulmea (Fries) Sydow & Sydow Stegophora aemula in China stating that the pathogen differs Synonyms: Gnomonia ulmea (Fries) Thümen, Sphaeria ulmea from ‘the closely related Gnomonia ulmea’ by the ‘mode of Fries, Dothidella ulmea (Fries) Ellis & Everhart, Lambro ulmea growth’ on elm. Since, 1999, S. ulmea has repeatedly been (Fries) E. Müller detected in consignments of bonsais from China, in UK and the Taxonomic position: Fungi: Ascomycetes: Diaporthales Netherlands, suggesting that the pathogen probably occurs in Notes on taxonomy and nomenclature: the anamorph is of China. In Europe, there is a doubtful record of ‘G. ulmicolum’ acervular type, containing both macroconidia, of ‘Gloeosporium’ on leaves and fruits of elm in Romania (Georgescu & Petrescu, type, and microconidia, of ‘Cylindrosporella’ type. Various cited by Peace (1962)), which has not been confirmed since. In anamorph names in different form-genera have been the Netherlands, S. ulmea was introduced into a glasshouse in used (‘Gloeosporium’ ulmeum ‘Gloeosporium’ ulmicolum, 2000, on ornamental bonsais, but was successfully eradicated Cylindrosporella ulmea, Asteroma ulmeum), -

Appendix 2: Plant Lists

Appendix 2: Plant Lists Master List and Section Lists Mahlon Dickerson Reservation Botanical Survey and Stewardship Assessment Wild Ridge Plants, LLC 2015 2015 MASTER PLANT LIST MAHLON DICKERSON RESERVATION SCIENTIFIC NAME NATIVENESS S-RANK CC PLANT HABIT # OF SECTIONS Acalypha rhomboidea Native 1 Forb 9 Acer palmatum Invasive 0 Tree 1 Acer pensylvanicum Native 7 Tree 2 Acer platanoides Invasive 0 Tree 4 Acer rubrum Native 3 Tree 27 Acer saccharum Native 5 Tree 24 Achillea millefolium Native 0 Forb 18 Acorus calamus Alien 0 Forb 1 Actaea pachypoda Native 5 Forb 10 Adiantum pedatum Native 7 Fern 7 Ageratina altissima v. altissima Native 3 Forb 23 Agrimonia gryposepala Native 4 Forb 4 Agrostis canina Alien 0 Graminoid 2 Agrostis gigantea Alien 0 Graminoid 8 Agrostis hyemalis Native 2 Graminoid 3 Agrostis perennans Native 5 Graminoid 18 Agrostis stolonifera Invasive 0 Graminoid 3 Ailanthus altissima Invasive 0 Tree 8 Ajuga reptans Invasive 0 Forb 3 Alisma subcordatum Native 3 Forb 3 Alliaria petiolata Invasive 0 Forb 17 Allium tricoccum Native 8 Forb 3 Allium vineale Alien 0 Forb 2 Alnus incana ssp rugosa Native 6 Shrub 5 Alnus serrulata Native 4 Shrub 3 Ambrosia artemisiifolia Native 0 Forb 14 Amelanchier arborea Native 7 Tree 26 Amphicarpaea bracteata Native 4 Vine, herbaceous 18 2015 MASTER PLANT LIST MAHLON DICKERSON RESERVATION SCIENTIFIC NAME NATIVENESS S-RANK CC PLANT HABIT # OF SECTIONS Anagallis arvensis Alien 0 Forb 4 Anaphalis margaritacea Native 2 Forb 3 Andropogon gerardii Native 4 Graminoid 1 Andropogon virginicus Native 2 Graminoid 1 Anemone americana Native 9 Forb 6 Anemone quinquefolia Native 7 Forb 13 Anemone virginiana Native 4 Forb 5 Antennaria neglecta Native 2 Forb 2 Antennaria neodioica ssp. -

AHP-Slippery

American Herbal Pharmacopoeia ® and herapeutic Compendium Slippery Elm Inner Bark Ulmus rubra Muhl. Standards of Analysis, Quality Control, and Therapeutics Editor Roy Upton RH DAyu Associate Editor Pavel Axentiev MS Research Associate Diana Swisher MA Authors Elan Sudberg Linda Haugen Final Reviewers Alkemists Laboratories Forest Health Protection, State and Costa Mesa, CA Private Forestry Karen Clarke History ® US Forest Service THAYERS Natural Remedies Josef Brinckmann Valeria Widmer Westport, CT CAMAG St. Paul, MN Traditional Medicinals Aviva Romm MD CPM RH (AHG) Sebastopol, CA Muttenz, Switzerland Allen Lockard American Botanicals American Herbalists Guild Roy Upton RH DAyu Therapeutics and Safety Eolia, MO Cheshire, CT ® American Herbal Pharmacopoeia James Snow RH (AHG) Scotts Valley, CA Francis Brinker ND Barry Meltzer Eclectic Institute, Inc. San Francisco Herbs & Natural Herbal Medicine Program Tai Sophia Institute Botanical Identification Program in Integrative Medicine Foods Co. University of Arizona Fremont, CA Laurel, MD Wendy Applequist PhD Tucson, AZ Andrew Weil MD Missouri Botanical Gardens Malcolm O’Neill Traditional Indications Complex Carbohydrate Research University of Arizona St. Louis, MO Tucson, AZ Roy Upton RH DAyu Center Macroscopic Identification American Herbal Pharmacopoeia University of Georgia Athens, GA Lynette Casper BA Scotts Valley, CA Planetary Herbals Art Presser PharmD Scotts Valley, CA International Status Huntington College of Health Josef Brinckmann Sciences Microscopic Identification Traditional -

City of Carrollton Summary of the Tree Preservation Ordinance (Ordinance 2520, As Amended by Ordinance 2622)

City of Carrollton Summary of the Tree Preservation Ordinance (Ordinance 2520, as amended by Ordinance 2622) A. Application & Exemptions 1. Ordinance applies to all vacant, unplatted or undeveloped property; property to be re- platted or redeveloped, and; public property, whether developed or not. 2. Ordinance does not apply to individual single-family or duplex residential lots after initial development/subdivision, provided that the use of the lot remains single-family or duplex residential. 3. Ordinance does not apply to Section 404 Permits issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 4. Routine pruning and maintenance is permitted, provided that it does not damage the health and beauty of the protected tree. B. Protected Trees 1. Only those kinds of trees listed on the Approved Plant List which are 4" in diameter or greater are protected. C. Preservation & Replacement 1. A plan to preserve or replace protected trees must be approved by the City before development or construction, or the removal of any protected tree. The plan must be followed. If no protected trees are present, a letter to that effect, signed by a surveyor, engineer, architect or landscape architect must be submitted to the City. 2. Protected trees to be removed must be replaced. Replacement trees must be chosen from the Approved Plant List, and be of a certain minimum size. Where 12 or more are to be replaced, no more than 34% of the replacement trees may be of the same kind. Replacement trees may be planted off-site, or a fee may be paid to the City instead of replacement, if there is/are no suitable location(s) on the subject property. -

Spotlight on Elm Pick Your Favorite fl Avor for Your Next Project by Joe Hurst-Wajszczuk

WoodSense Spotlight on Elm Pick your favorite fl avor for your next project By Joe Hurst-Wajszczuk Red Elm White Elm A century ago, Dutch Elm creamy white to darker brown Disease (DED) decimated (the darker heartwood can millions of elm trees, many special applications: First, red be easily confused with red). of which adorned American elm’s split-resistant interlocking White elm may show some city streets. (Fun fact: “Elm” grain made it a prized wood staining, but this does not affect is the 15th most common for hoof-resistant barn �loor the wood’s integrity. Red elm street name in the USA.) The underplanks. normal Secondly, conditions, although elm the remains in the darker red- encouraging news is that these wood is susceptible to decay fast-growing trees are enjoying contact with water. This unusual a comeback. Elm lumber still resists rot when kept in constant brown spectrum and does not isn’t as readily available as display a major color difference other domestic hardwoods, af�inity made it a natural choice mindfulbetween ofsap the and grain. heartwoods. The wild days,for barrels, elm is shipbest keels,reserved and for even Color is important, but be tricky, but it’s worth the hunt. below-ground water pipes. These so This�inding striking a supplier hardwood can be duepatterns to alternating of �latsawn grain) boards are is affordable and easy to smaller projects, primarily due enchanting,(often with ribbon-like but elm’s working �igure Whereto its poor the dimensional wood comes stability. from Elms grow east of the Rockies, arework. -

Appendix B Existing Vegetation Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie Final Environmental Impact Statement

Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie Final Environmental Impact Statement APPENDIX B EXISTING VEGETATION CONTENTS 1. Terrestrial Natural Communities (Native Vegetation) .........................B-1 1.1. Floodplain Forests.................................................................................B-1 1.2. Upland Forests......................................................................................B-2 1.3. Woodlands............................................................................................B-2 1.4. Savannas ..............................................................................................B-2 1.1. Seeps....................................................................................................B-3 1.1. Marshes ................................................................................................B-3 1.1. Sedge meadow .....................................................................................B-3 1.1. Typic Prairie ..........................................................................................B-4 1.9. Dolomite Prairie.....................................................................................B-5 2. Cultural and Successional Communities.............................................B-6 2.1. Developed and intensively managed lands...........................................B-6 2.2. Croplands..............................................................................................B-6 2.3. Agricultural Grasslands .........................................................................B-6 -

Maine Tree Species Fact Sheet

Maine Tree Species Fact Sheet Common Name: Slippery Elm (Red Elm) Botanical Name: Ulmus rubra Tree Type: Deciduous Physical Description: Growth Habit: Slippery elm is a medium-sized tree of moderately fast growth that may live to be 200 hundred years old. It grows best on moist, rich soils of lower slopes and flood plains. The bark is thick; dark brown tinged with red, divided by shallow fissures into flat ridges and covered with flat scales. The inner bark is sticky when chewed. The twigs are light gray in color, http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/FORESTRY/commontr/images/SlipperyElm.gif hairy, and somewhat rough. The alternate, simple, elliptical and long-pointed leaves have doubly serrate margins and are 5-7 inches long. They are thick, rough, and dark green in color. The undersides of the leaves are paler with white hairs and have a prominent midrib and parallel veins. Height: Slippery elm grows to a height of 50 feet and has an average trunk diameter of 2 feet. Shape: Slippery elm is an open-branched tree. Fruit/Seed Description/Dispersal Methods: Slippery elm has inconspicuous, perfect flowers that appear in the spring before the leaves. The seeds are small, flattened and winged. They ripen from April to June and are dispersed by the wind as soon as they are ripe. Range within Maine: Slippery elm is extremely rare in the state. It does however; occur naturally in scattered locations in York and Franklin Counties. This species is hardy to Zone 3. Distinguishing Features: The inner bark and twigs are chewy. -

Woodsense Spotlight on Elm the Once-Common Commercial Hardwood We Almost Lost

WoodSense Spotlight on Elm The once-common commercial hardwood we almost lost By Pete Stephano Technical consultant: Larry Osborn Elm may not be as conspicuous Britain’s most prominent is and popular as are many of the English elm (Ulmus procera), Europe employed elm–even the “cabinet class” wood species in which is called Carpathian famed English long bow was modern-day furniture making elm in continental Europe. occasionally crafted of it when and woodworking. After all, No matter the individual elm bowyers lacked the preferred the three most common North species, the stock shares similar yew. Elm was even favored for American elms represent qualities, except that rock elm the keels of English sailing ships; only about three percent of all is harder and heavier. Flatsawn in fact, much American elm was commercially available domestic elm boards can sometimes exported for that very purpose. hardwoods. That’s mainly due exhibit a distinctive “W” or Surprisingly, elm resists decay to the fast-spreading Dutch bird-feather grain patterns. The when in constant contact with elm disease of the 1950s and wood has open, coarse grain water, so bored-out elm (along 1960s that devastated millions much like white ash that is with hemlock) logs ended up as of stately elms from the East most often interlocked, making below-ground city water pipes in Coast to the Midwest as well as in 18th-century Europe and America. Great Britain and Europe, nearly Although only moderately In the United States, elm’s early wiping out the species. Since strong,it somewhat elm bends difficult easily, to work. -

Download (1MB)

'l t, E!564roB rrrr. tr.etrp"*trrsFarogr.lq ff{rerrqPer f'lTr^ tE.) |'' ,lj.: l tt'-' . i. : -::.1r,'.1 . ' ';"4" '. 'cdfi ;;, ryltotr m nE rinurgrrpu tS6o ib tgz .' Int lloauction Thls paper Bive6 a cLassifiea biblioSraphy of th€ ecol-ogy s.na tar(onorry of the genus Ulltus frosr 196A tu 1972. The bibliography has beon corspileal by a search of Forestr? Abstracts and Biolot-ical- Abstracts, and is beli€ved to be reasonab\r corPlete. The paper is in two parts:- A classification of the vafious papers by the Oxford Doci-rDalSysten, givilg tbe titles of the papers ana the authors. A list of pepo!6, including autho$, titles, o!'i8inal pl.ace of publice.tion, anil refelence number in Forestly Abstracts an4/or giologicat Abstrects. CI,ASSIIDATION OF' lI6TND PAPNRJBY OXI'ORDDNCI}UJ SYSTIM 1. IACTOR.SOI THE NIi1IRONI{ENT. BiOI,OGY 11. Site flcrors: clirur. situ6!i.r . soil, hyalroloRy (rrater consel"votLon.soil consen/aLio' snij srosion) 111+. Soi1. Soil scicnce r lr, c, :^i 1 for+: l i Irycsti€ation ol the relationship betrieen soil ?roperties enA the grovrth of Siberian Fln Lroaa i? rLn l4asc -lai - -l'Nebraska. Sanders, D.H. '1967 16, Ce4cIAl !9&Itl 16A. Plant c4qqlq!ry 16a.2 C!9!i94-!9 npo s iti on q+d]] lii, ^l n^lrmlrar.r 1^ fron native species of Ulrus; Bedlarska, D. 1971 PolJ4)henols axrd aliscolorations in the'ela dis -as L'wrstigated bJ hisLochenic€.I techniques. eag!\ot\, C. 1967 PerDxidsse in healthy ana aiseased eln trces investi8ated bj. -

The Occurrence of Slippery Elm (Ulmus Rubra Muhl.) Root Sprouts in Forest Understories in East-Central Illinois

Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science received 2/11/97 (1998), Volume 91, 1 and 2, pp.13-17 accepted 5/30/97 The Occurrence of Slippery Elm (Ulmus rubra Muhl.) Root Sprouts in Forest Understories in East-central Illinois Rodney W. Davis, Richard L. Larimore, and John E. Ebinger Botany Department Eastern Illinois University Charleston, Illinois 61920 ABSTRACT Ulmus rubra Muhl. (slippery elm) is the dominant woody understory species of many mesic forests of east-central Illinois. Most slippery elm seedlings and small saplings are sprouts from horizontal roots that grow in the top 5 cm of the soil. Of the specimens examined the horizontal roots were between 6 and 457 cm long, and with one to 31 sprouts. These sprouts, which were usually less than 1 m tall, ranged from one to nine years in age. The sprouts only rarely develop into larger saplings. INTRODUCTION Ulmus rubra Muhl. (slippery elm) is a common species of deciduous forests throughout most of eastern United States (Braun 1950, Gleason and Cronquist 1991). Prior to European settlement elms were common in many Illinois forests (Kilburn 1959, Ebinger 1986, 1987, Rodgers and Anderson 1979). Presently elms, particularly slippery elm, are still common in the overstory. In the uplands of Hart Memorial Woods, Champaign County, slippery elm ranked third in importance value (IV), and dominated the smaller diameter classes (Johnson et al. 1978). Similar results were obtained for Funk Forest Natural Area, part of an extensive prairie grove in McLean County, where slippery elm ranked sixth in IV (Cox et al. 1972). -

Impacts of Native and Non-Native Plants on Urban Insect Communities: Are Native Plants Better Than Non-Natives?

Impacts of Native and Non-native plants on Urban Insect Communities: Are Native Plants Better than Non-natives? by Carl Scott Clem A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama December 12, 2015 Key Words: native plants, non-native plants, caterpillars, natural enemies, associational interactions, congeneric plants Copyright 2015 by Carl Scott Clem Approved by David Held, Chair, Associate Professor: Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Charles Ray, Research Fellow: Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Debbie Folkerts, Assistant Professor: Department of Biological Sciences Robert Boyd, Professor: Department of Biological Sciences Abstract With continued suburban expansion in the southeastern United States, it is increasingly important to understand urbanization and its impacts on sustainability and natural ecosystems. Expansion of suburbia is often coupled with replacement of native plants by alien ornamental plants such as crepe myrtle, Bradford pear, and Japanese maple. Two projects were conducted for this thesis. The purpose of the first project (Chapter 2) was to conduct an analysis of existing larval Lepidoptera and Symphyta hostplant records in the southeastern United States, comparing their species richness on common native and alien woody plants. We found that, in most cases, native plants support more species of eruciform larvae compared to aliens. Alien congener plant species (those in the same genus as native species) supported more species of larvae than alien, non-congeners. Most of the larvae that feed on alien plants are generalist species. However, most of the specialist species feeding on alien plants use congeners of native plants, providing evidence of a spillover, or false spillover, effect. -

Elmcare.Com - All About Elm Trees and Elm Tree Care

Elmcare.com - All about elm trees and elm tree care. Home | Elm Care Products | Register your Elm | Forum Last Update 17/12/01 Customized Elm Tree Care Kits Did you know a new wild bird seed has been developed and tested that Custom care kits include actually repels squirrels? How Trees Work specialized and innovative soil Click here to learn about Squirrel Proof Wild Bird treatments designed to promote About Elm Trees Seed. root development and the long- Caring for Your Elm term health and vitality of your Elm Tree Diseases elm. A healthier elm will be better able to fight against Dutch elm disease. Elm Tree Links more Quick Elm Facts Elm Tree Registry Visit TreeHelp.com for all of your tree and shrub Register your elm tree to receive customized care care needs advice...more. Return of the Stately Elm Writer and broadcaster Jamie Swift examines the Canadian city of Winnipeg's struggle to combat Dutch elm disease. Through the work of community groups like the Coalition to Save the Elms and innovative technology, the city has achieved substantial success... more. http://www.elmcare.com/index.htm (1 of 2) [2/27/02 10:29:57 PM] Elmcare.com - All about elm trees and elm tree care. New Treatments for Elms in History Elm Tree Links Dutch Elm Disease? Look at elms in the context of Links to a growing community of Researchers examine new ways to human history. academics, homeowners and fight this devastating disease. professional tree care experts. Elms in Literature Elm Species Quick Elm Facts Read what some of the world's Elms come in many sizes and leading poets and authors have Discover something new and shapes...learn about them all.