Juglans Cinerea) for C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation and Management of Butternut Trees

Purdue University Purdue extension FNR-421-W & Natural Re ry sou Forestry and Natural Resources st rc re e o s F Conservation and Management of Butternut Trees Lenny Farlee1,3, Keith Woeste1, Michael Ostry2, James McKenna1 and Sally Weeks3 1 USDA Forest Service Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 PURDUE UNIVERSITY 2 USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, 1561 Lindig Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108 3 Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 Introduction Butternut (Juglans cinerea), also known as white wal- nut, is a native hardwood related to black walnut (Juglans nigra) and other members of the walnut family. Butternut is a medium-sized tree with alternate, pinnately com- pound leaves, that bears large, sharply ridged, cylindrical nuts inside sticky green hulls that earned it the nickname lemon-nut (Rink, 1990). The nuts, a preferred food of squirrels and other wildlife, were collected and eaten by Native Americans (Waugh, 1916; Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975) and early settlers, who also valued butternut for its workable, medium brown-colored heartwood (Kel- logg, 1919), and as a source of medicine (Johnson, 1884; Lawrence, 1998), dyes (Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975), and sap sugar. Butternut’s native range extends over the entire north- eastern quarter of the United States, including many states immediately west of the Mississippi River. Butter- nut is more cold-tolerant than black walnut, and it grows as far north as the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, New Brunswick, southern Quebec, and Ontario (Fig.1). -

Conservation Assessment for Butternut Or White Walnut (Juglans Cinerea) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region

Conservation Assessment for Butternut or White walnut (Juglans cinerea) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region 2003 Jan Schultz Hiawatha National Forest Forest Plant Ecologist (906) 228-8491 This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on Juglans cinerea L. (butternut). This is an administrative review of existing information only and does not represent a management decision or direction by the U. S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was gathered and reported in preparation of this document, then subsequently reviewed by subject experts, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if the reader has information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for Butternut or White walnut (Juglans cinerea) L. 2 Table Of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION / OBJECTIVES.......................................................................7 BIOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION..............................8 Species Description and Life History..........................................................................................8 SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS...........................................................................9 -

Juglans Nigra Juglandaceae L

Juglans nigra L. Juglandaceae LOCAL NAMES English (walnut,American walnut,eastern black walnut,black walnut); French (noyer noir); German (schwarze Walnuß); Portuguese (nogueira- preta); Spanish (nogal negro,nogal Americano) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Black walnut is a deciduous tree that grows to a height of 46 m but ordinarily grows to around 25 m and up to 102 cm dbh. Black walnut develops a long, smooth trunk and a small rounded crown. In the open, the trunk forks low with a few ascending and spreading coarse branches. (Robert H. Mohlenbrock. USDA NRCS. The root system usually consists of a deep taproot and several wide- 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office spreading lateral roots. guide to plant species) Leaves alternate, pinnately compound, 30-70 cm long, up to 23 leaflets, leaflets are up to 13 cm long, serrated, dark green with a yellow fall colour in autumn and emits a pleasant sweet though resinous smell when crushed or bruised. Flowers monoecious, male flowers catkins, small scaley, cone-like buds; female flowers up to 8-flowered spikes. Fruit a drupe-like nut surrounded by a fleshy, indehiscent exocarp. The nut has a rough, furrowed, hard shell that protects the edible seed. Fruits Bark (Robert H. Mohlenbrock. USDA NRCS. 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office produced in clusters of 2-3 and borne on the terminals of the current guide to plant species) season's growth. The seed is sweet, oily and high in protein. The bitter tasting bark on young trees is dark and scaly becoming darker with rounded intersecting ridges on maturity. BIOLOGY Flowers begin to appear mid-April in the south and progressively later until early June in the northern part of the natural range. -

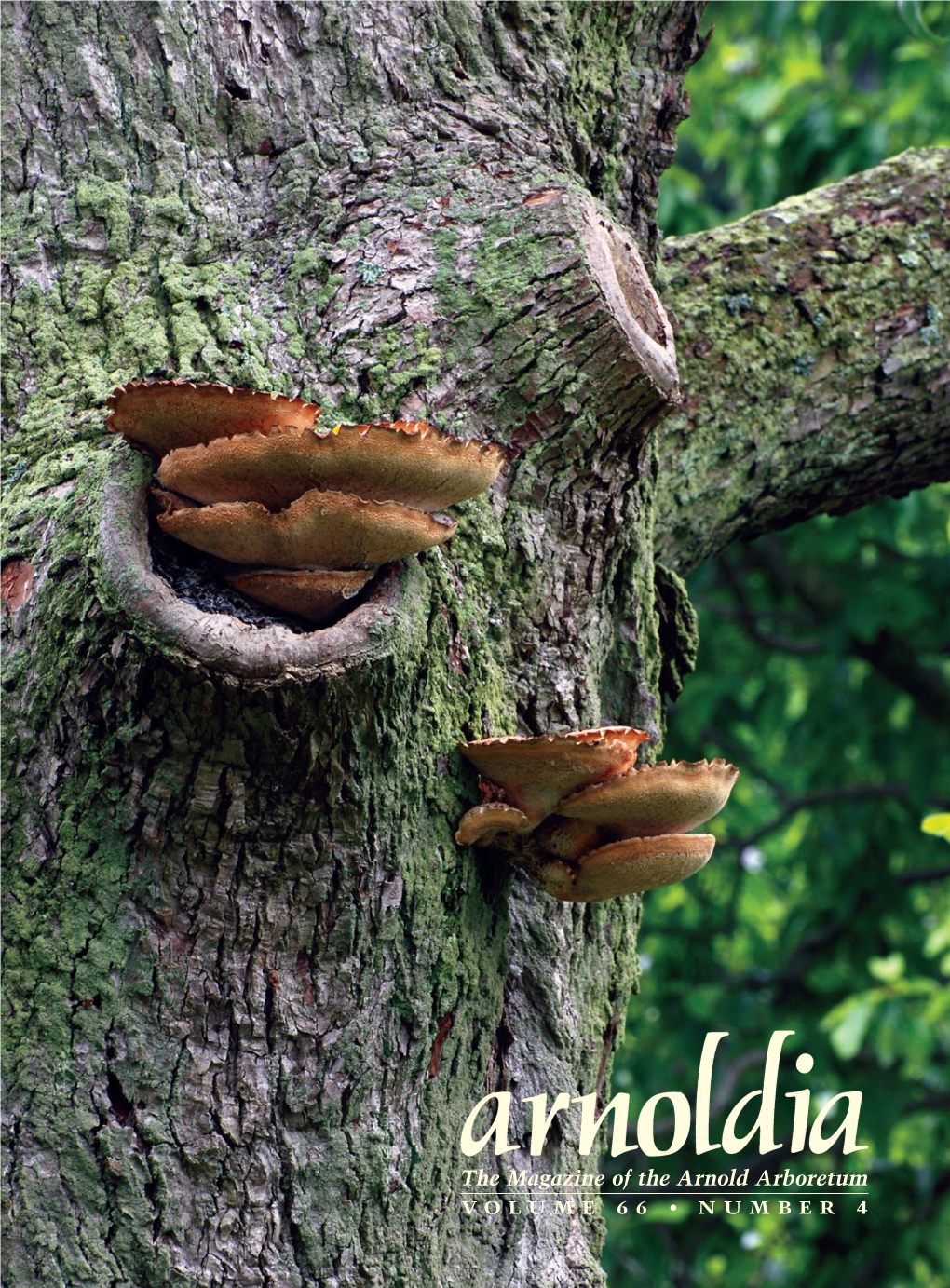

Juglans Spp., Juglone and Allelopathy

AllelopathyJournatT(l) l-55 (2000) O Inrernationa,^,,r,':'r::;:';::::,:rt;SS Juglansspp., juglone and allelopathy R.J.WILLIS Schoolof Botany.L.iniversity of Melbourre,Parkville, Victoria 3052, ALrstr.alia (Receivedin revisedform : February 26.1999) CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. HistoricalBackground 3. The Effectsof walnutson otherplants 3.i. Juglansnigra 3.1.1.Effects on cropplants 3. I .2. Eft'ectson co-plantedtrees 3. 1 .3 . Effectson naturalvegetation 3.2. Juglansregia 3.2.1. Effectson otherplalrts 3.2.2.Effects on phytoplankton 1.3. Othel walnuts : Juglans'cinerea, J. ntttlor.J. mandshw-icu 4. Juglone 5. Variability in the effect of walnut 5.1. Intraspecificand Interspecific variation 5.2. Seasonalvariation 5.3 Variation in the effect of Juglansnigra on other.plants 5.4. Soil effects 6. Discussion Ke1'rvords: Allelopathy,crops, history, Juglan.s spp., juglone. phytoplankton,walnut, soil, TTCCS 1. INTRODUCTION The"rvalnuts" are referable to Juglans,a genusof 20-25species with a naturaldistribution acrossthe Northern Hemisphere and extending into SouthAmerica. Juglans is a memberof thefamily Juglandaceae which contains6 or 7 additionalgenera including Cruv,a, Cryptocctrva and a total of about 60 species. Walnuts are corrunerciallyimportant as the sourceof the ediblewalnut, the highly prizedtimber and as a specimentrees. Eating walnutsare usually obtarnedfrom -/. regia (the colrunonor Persianwalnut, erroneousll'known as the English walnut)- a nativeof SEEurope and Asia, which haslong been cultivated, but arealso sometin.res availablelocally from other speciessuch as J. nigra (back walnut) - a native of eastern North America andJ. ntajor, J. calfornica andJ. hindsii, native to the u,esternu.S. ILillis Grafting of supcrior fnrit-bearing scions of J. regia onlo rootstocksof hlrdier spccics. -

Curriculum Vitae Name

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME Kirk Broders ADDRESS PHONE Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management (970) 491-0850 College of Agricultural Sciences EDUCATION 2008 Ph D, The Ohio State University 2004 BS, University of Nebraska-Lincoln ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2017-2018 - Assistant Professor (College of Agricultural Sciences) 2016-2017 - Assistant Professor (College of Agricultural Sciences) 2015-2016 (College of Agricultural Sciences) OTHER POSITIONS August 2015 - Present Assistant Professor, BSPM, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, United States. 2011 - 2015 Assistant Professor, University of New Hampshire, United States. 2009 - 2010 Post-doctoral Research Fellow, University of Guelph, United States. PUBLISHED WORKS Refereed Journal Articles Broders, K. D., Munck, I., Wyka, S., Iriarte, G., Beaudoin, E. (2015). Characterization of Fungal Pathogens Associated with White Pine Needle Damage (WPND) in Northeastern North America. Forests, 6(11), 4088-4104., Peer Reviewed/Refereed Munck, I. A., Livingston, W., Lombard, K., Luther, T., Ostrofsky, W. D., Weimer, J., Wyka, S., Broders, K. D. (2015). Extent and Severity of Caliciopsis Canker in New England, USA: An Emerging Disease of Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus L.). Forests, 6(11), 4360-4373., Peer Reviewed/Refereed Boraks, A. W., Broders, K. D. (in press). Population genetics of butternut (Juglans cinerea) in the northeastern United States. Conservation Genetics., Peer Reviewed/Refereed Laflamme, G., Broders, K. D., Côté, C., Munck, I., Iriarte, G., Innes, L. (2015). Priority of Lophophacidium over Canavirgella: taxonomic status of Lophophacidium dooksii and Canavirgella banfieldii, causal agents of a white pine needle disease. Mycologia, 107(4), 745-753., Peer Reviewed/Refereed Broders, K. D., Boraks, A., Barbison, L., Brown, J. R., Boland, G. -

Identification of Butternuts and Butternut Hybrids

Purdue University Purdue extension FNR-420-W & Natural Re ry sou Forestry and Natural Resources st rc re e o s F Identification of Butternuts and Butternut Hybrids Lenny Farlee1,3, Keith Woeste1, Michael Ostry2, James McKenna1 and Sally Weeks3 1 USDA Forest Service Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 PURDUE UNIVERSITY 2 USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, 1561 Lindig Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108 3 Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 Introduction Butternut (Juglans cinerea), also known as white walnut, is a native hardwood related to black walnut (Juglans nigra) and other members of the walnut family. Butternut is a medium-sized tree with alternate, pinnately compound leaves that bears large, sharply ridged and corrugated, elongated, cylindrical nuts born inside sticky green hulls that earned it the nickname lemon-nut (Rink, 1990). The nuts are a preferred food of squirrels and other wildlife. Butternuts were collected and eaten by Native Americans (Waugh, 1916; Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975) and early settlers, who also valued butternut for its workable, medium brown-colored wood (Kellogg, 1919), and as a source of medicine (Johnson, 1884), dyes (Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975), and sap sugar. Butternut’s native range extends over the entire north- eastern quarter of the United States, including many states immediately west of the Mississippi River, and into Canada. Butternut is more cold-tolerant than black walnut, and it grows as far north as the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, New Brunswick, southern Quebec, and Figure 1. -

Brewing Beer with Native Plants (Seasonality)

BREWING BEER WITH INDIANA NATIVE PLANTS Proper plant identification is important. Many edible native plants have poisonous look-alikes! Availability/When to Harvest Spring. Summer. Fall Winter . Year-round . (note: some plants have more than one part that is edible, and depending on what is being harvested may determine when that harvesting period is) TREES The wood of many native trees (especially oak) can be used to age beer on, whether it be barrels or cuttings. Woods can also be used to smoke the beers/malts as well. Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga Canadensis): Needles and young twigs can be brewed into a tea or added as ingredients in cooking, similar flavoring to spruce. Tamarack (Larix laricina): Bark and twigs can be brewed into a tea with a green, earthy flavor. Pine species (Pinus strobus, Pinus banksiana, Pinus virginiana): all pine species have needles that can be made into tea, all similar flavor. Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana): mature, dark blue berries and young twigs may be made into tea or cooked with, similar in flavor to most other evergreen species. Pawpaw (Asimina triloba): edible fruit, often described as a mango/banana flavor hybrid. Sassafras (Sassafras albidum): root used to make tea, formerly used to make rootbeer. Similarly flavored, but much more earthy and bitter. Leaves have a spicier, lemony taste and young leaves are sometimes used in salads. Leaves are also dried and included in file powder, common in Cajun and Creole cooking. Northern Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis): Ripe, purple-brown fruits are edible and sweet. Red Mulberry (Morus rubra): mature red-purple-black fruit is sweet and juicy. -

Early Season Softwood Cuttings Effective for Vegetative Propagation

1973; Shreve, 1972; Shreke and Miles, 1972), J. regin (Cautam and Chauhan, 1990), J. sirzeizsis (Kwon et al.. 1990),and hybrids (Reil Early Season Softwood Cuttings et al., 1998: S~IT,1964). The objective of this study was to deter- Effective for Vegetative Propagation of mine the conditions necessary for successful hardwood or softwood cutting propagation of butternut. Preliminary studies in 1998 with Juglans cznerea hardwood cuttings collected in May resulted Paula M. Pijut%nd Melanie J. Moore in 12.5% rooting when cuttings were treated with 29 mM K-IBA, but only three out of six USf>d.Forest Service, NortJz Cerztml Research Station, 1992 Folnlell Avenue, plants surviked acclimatization to the tkld St. Paul, MN 55108 (Pijut and Barker, 1999). Softwood cuttings collected in June and July resulted in 63% to Additiclnal i~dexttsorcj.r. butternut, adventitious rooting, threatened species 70% rooting when cuttings were treated with Abstmct. Juglans cinerea L. (butternut) is a hardwood species valued for its wood and 62 mM K-IBA or 74 mM IBA, but again only edible nuts. Information on the vegetative propagation of this species is currently unavail- three out of 68 plants survived overwintering able. Our objective was to determine the conditions necessary for successful stem-cutting and acclimatization to the field. Based on propagation of butternut. In 1999 and 2000,10 trees (each year) were randomly selected these observations, for the years 1999 and from a 5- and 6-year-old butternut plantation located in Rosemount, Minn. Hardwood 2000, we examined the effects of propagation stem cuttings were collected in March, April, and May. -

Systematics of the Genus Ramaria Inferred from Nuclear Large Subunit And

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Andrea J. Humpert for the degree of Master of Science in Botany and Plant Pathology presented on November 11, 1999. Title: Systematics of the Genus Ramaria Inferred from Nuclear Large Subunit and Mitochondrial Small Subunit Ribosomal DNA Sequences. Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy Joseph W. Spatafora Ramaria is a genus of epigeous fungi common to the coniferous forests of the Pacific Northwest of North America. The extensively branched basidiocarps and the positive chemical reaction of the context in ferric sulfate are distinguishing characteristics of the genus. The genus is estimated to contain between 200-300 species and is divided into four subgenera, i.) R. subgenus Ramaria, ii.) R. subgenus Laeticolora, iii.) R. subgenus Lentoramaria and iv.) R. subgenus Echinoramaria, according to macroscopic, microscopic and macrochemical characters. The systematics of Ramaria is problematic and confounded by intraspecific and possibly ontogenetic variation in several morphological traits. To test generic and intrageneric taxonomic classifications, two gene regions were sequenced and subjected to maximum parsimony analyses. The nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA (nuc LSU rDNA) was used to test and refine generic, subgeneric and selected species concepts of Ramaria and the mitochondrial small subunit ribosomal DNA (mt SSU rDNA) was used as an independent locus to test the monophyly of Ramaria. Cladistic analyses of both loci indicated that Ramaria is paraphyletic due to several non-ramarioid taxa nested within the genus including Clavariadelphus, Gautieria, Gomphus and Kavinia. In the nuc LSU rDNA analyses, R. subgenus Ramaria species formed a monophyletic Glade and were indicated for the first time to be a sister group to Gautieria. -

Stinkhorns of the Ns of the Hawaiian Isl Aiian Isl Aiian Islands

StinkhorStinkhornsns ofof thethe HawHawaiianaiian IslIslandsands Don E. Hemmes1* and Dennis E. Desjardin2 Abstract: Additional members of the Phallales are recorded from the Hawaiian Islands. Aseroë arachnoidea, Phallus atrovolvatus, and a Protubera sp. have been collected since the publication of the field guide Mushrooms of Hawaii in 2002. A complete list of species and their distribution on the various islands is included. Figure 1. Aseroë rubra is commonly encountered in Eucalyptus plantations Key Words: Phallales, Aseroë, Phallus, Mutinus, Dictyophora, in Hawai’i but these fruiting bodies are growing in wood chip mulch surrounding landscape plants in a park. Pseudocolus, Protubera, Hawaii. Roger Goos made the earliest comprehensive record of mem- bers of the Phallales in the Hawaiian Islands (Goos, 1970) and listed Anthurus javanicus (Penzig.) G. Cunn., Aseroë rubra Labill.: Fr., Dictyophora indusiata (Vent.: Pers.) Desv., Linderiella columnata (Bosc) G. Cunn., and Phallus rubicundus (Bosc) Fr. Later, Goos, along with Dring and Meeker, described the unique Clathrus spe- cies, C. oahuensis Dring (Dring et al., 1971) from the Koko Head Desert Botanical Gardens on Oahu. The records of Dictyophora indusiata and Linderiella columnata in Goos’s paper actually came from observations by N. A. Cobb in the early 1900’s (Cobb, 1906; Cobb, 1909) who reported these two species in sugar cane fields on Hawai’i Island (also known as the Big Island) and Kaua’i, re- spectively, and thought they might be parasitic on sugar cane. To our knowledge, neither Linderiella columnata (now known as Figure 2. Aseroë arachnoidea forming fairy rings on a lawn in Hilo. Clathrus columnatus Bosc) nor Clathrus oahuensis has been seen in the islands since these early observations. -

Phylogenetic Relationships of the Gomphales Based on Nuc-25S-Rdna, Mit-12S-Rdna, and Mit-Atp6-DNA Combined Sequences

fungal biology 114 (2010) 224–234 journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/funbio Phylogenetic relationships of the Gomphales based on nuc-25S-rDNA, mit-12S-rDNA, and mit-atp6-DNA combined sequences Admir J. GIACHINIa,*, Kentaro HOSAKAb, Eduardo NOUHRAc, Joseph SPATAFORAd, James M. TRAPPEa aDepartment of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-5752, USA bDepartment of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science (TNS), Tsukuba-shi, Ibaraki 305-0005, Japan cIMBIV/Universidad Nacional de Cordoba, Av. Velez Sarfield 299, cc 495, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina dDepartment of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA article info abstract Article history: Phylogenetic relationships among Geastrales, Gomphales, Hysterangiales, and Phallales Received 16 September 2009 were estimated via combined sequences: nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA (nuc-25S- Accepted 11 January 2010 rDNA), mitochondrial small subunit ribosomal DNA (mit-12S-rDNA), and mitochondrial Available online 28 January 2010 atp6 DNA (mit-atp6-DNA). Eighty-one taxa comprising 19 genera and 58 species were inves- Corresponding Editor: G.M. Gadd tigated, including members of the Clathraceae, Gautieriaceae, Geastraceae, Gomphaceae, Hysterangiaceae, Phallaceae, Protophallaceae, and Sphaerobolaceae. Although some nodes Keywords: deep in the tree could not be fully resolved, some well-supported lineages were recovered, atp6 and the interrelationships among Gloeocantharellus, Gomphus, Phaeoclavulina, and Turbinel- Gomphales lus, and the placement of Ramaria are better understood. Both Gomphus sensu lato and Rama- Homobasidiomycetes ria sensu lato comprise paraphyletic lineages within the Gomphaceae. Relationships of the rDNA subgenera of Ramaria sensu lato to each other and to other members of the Gomphales were Systematics clarified. -

Master Gardeners Volume XXIV, Issue 1 December16/January17

For the Cherokee County Master Gardeners Volume XXIV, Issue 1 December16/January17 What’s Happening Editor’s Corner By Marcia Winchester, December Cherokee County Master Gardener Dec 1- Demo Garden Workday Driving through my neighborhood I learn a lot about my neighbors and 10-2 their gardening habits. Some neighbors hire others to mow and maintain their yards. They are oblivious to plants growing in their landscapes. I’ve Dec 3 - Crafting a Holiday seen poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) growing in shrubs, small trees Wreath, 10am, Senior that have reseeded by electric boxes, and this year I even spotted kudzu Center (Pueraria lobata) that has covered several large Leylands (Cupressus X leylandii). Dec 15 - Demo Garden Workday Dec 17—Holiday Party, 6pm The opposite extreme is the gardener that tries to control Mother @Woodmont Clubhouse Nature. A number of these controllers have pruned their weeping Japanese maples into tidy “meatballs” to match their tidy “meatball” shrubs. I love the weeping branches of my 19-year-old Japanese maple. Dec 31 - 2016 Hours due at Her unique shape makes her the shining star in my front yard. One extension neighbor has gone as far as pruning his native dogwood trees (Cornus florida) into “meatballs.” They are almost unrecognizable. The most Dec 26– Jan 3 - Extension office abused pruning in Cherokee County landscapes is done to crape myrtles closed for the holidays (Lagerstroemia indica). The number one rule is that they should not be pruned until late February or early March. Pruning encourages growth, January which is not a good thing in the winter.