Overcoming Sin: Comparing Dante’S Inferno and the New Testament to Cormac Mccarthy’S Outer Dark and Child of God

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Suzanne Fischer Dissertation

Diseases of Men: Sexual Health and Medical Expertise in Advertising Medical Institutes, 1900-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Suzanne Michelle Fischer IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Sally Gregory Kohlstedt August, 2009 © Suzanne Fischer 2009 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. i Acknowledgements Many thanks to my advisor, Sally Gregory Kohlstedt and the members of my committee for their assistance. Thanks also to Susan Jones, Mike Sappol and others who provided guidance. Many archivists and librarians assisted my research, including Christopher Hoolihan at the Miner Medical Library, Elaine Challacombe and Jim Curley at the Wangensteen Historical Library, Elizabeth Ihrig at the Bakken, and the staff of the Archives of the American Medical Association. Many thanks to my father and to my late mother. Members of DAWGs, the Dissertation and Writers Group, including Susan Rensing, Margot Iverson, Juliet Burba, Don Opitz, Hyung Wook Park, Gina Rumore, Rachel Mason Dentinger, Erika Dirkse, Amy Fisher and Mike Ziemko provided helpful commentary. Many friends, including Katherine Blauvelt, Micah Ludeke, Mary Tasillo, Megan Kocher, Meghan Lafferty, Cari Anderson, Christine Manganaro and Josh Guttmacher provided support and dinner. And endless gratitude to my greatest Friend. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Barbara Fischer. -

The Sunset Limited Press Release

588 Sutter Street #318 San Francisco, CA 94102 415.677.9596 fax 415.677.9597 www.sfplayhouse.org PRESS RELEASE VENUE: 533 Sutter Street, @ Powell For immediate release Contact: Susi Damilano August, 2010 [email protected] West Coast Premiere of THE SUNSET LIMITED By Cormac McCarthy Directed by Bill English September 28 through November 6th Press Opening: October 2nd San Francisco, CA (August 2010) - The SF Playhouse (Bill English, Artistic Director; Susi Damilano, Producing Director) are thrilled to announce casting for the West Coast Premiere of The Sunset Limited by Cormac McCarthy which opens their eighth season. “The theme of the 2010-2011 season is ‘Why Theatre?”, remarked English. “Why do we do theatre? How does theatre serve our community?” Each of our selections for our eighth season will give a different answer to these questions. Based on the belief that mankind created theatre to serve a spiritual need in our community, our riskiest and most challenging season yet will ask us to face mankind’s deepest mysteries. We open the season with one of the most powerful writers of our time, Cormac McCarthy (All the Pretty Horses, The Road, No Country for Old Men). The play, billed as “a novel in play form” brings us into a startling encounter on a New York subway platform which leads two strangers to a run-down tenement where they engage in a brilliant verbal duel on a subject no less compelling than the meaning of life. TV and film star Carl Lumbly (Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train, Alias, Cagney & Lacey) returns to the SF Playhouse to reunite with local favorite Charles Dean (White Christmas, Awake and Sing!) after having performed together in Berkeley Rep’s 1997 production of Macbeth. -

A Translation Autopsy of Cormac Mccarthy's The

A TRANSLATION AUTOPSY OF CORMAC MCCARTHY’S THE SUNSET LIMITED IN SPANISH: LITERARY AND FILM CODA Michael Scott Doyle [T]he translation is not the work, but a path toward the work. —José Ortega y Gasset, “The Misery and Splendor of Translation,” 109 We now have the personal word of the author’s to be transformed into a personal word of the trans- lator’s. As always with translation, this calls for a choice among synonyms. —Gregory Rabassa, If This Be Treason: Translation and Its Dyscontents, 12–13 Glossary of the Codes Used S1 = the first Spanish TLT version to be analyzed = Y1,theliterary translation-in-progress S2 = the second Spanish TLT version to be analyzed = Y2, the final, published literary translation S3 = the third Spanish TLT version to be analyzed = the movie subtitles S4 = the fourth Spanish TLT version to be analyzed = the movie dubbing SLT-E = Source Language Text English (Translation from English) SLT-X = Source Language Text in X Language (Translation from Language X) TLT = Target Language Text TLT-S = Target Language Text Spanish (translation into Spanish) Y1 = Biopsy Stage of a Translation = the Translation-in-Progress (in the Process of Being Translated) Y2 = Autopsy Stage of a Translation = the Final Published Translation (Post-process of the Act of Translating, an Outcome of Y1) Introduction: From Biopsy to Autopsy The literary translation criticism undertaken in the Sendebar article “A Translation Biopsy of Cormac McCarthy’s The Sunset Limited in Spanish: Shadowing the Re-creative Process” antici- pates a postmortem -

“Constructed on No Known Paradigm”: Novelistic Form and the Southern City in Cormac Mccarthy’S Suttree

“Constructed on no known paradigm”: Novelistic Form and the Southern City in Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree Andrew James Dykstal Bachelor of Arts, Hillsdale College, 2013 A thesis presented to the graduate faculty of the University of Virginia in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia April 2017 Dykstal 1 This thesis is dedicated to my peers and teachers at UVA and Hillsdale College, with particular bows to Jerry McGann—my thesis director—and to Michael Levenson, both mentors whose patience, encouragement, and graceful professionalism have shaped my thinking and my aspirations; to Fred and Carol Langley and the members of the American Legion whose generosity made possible my graduate education; and to my grandfather Cornelius Dykstal, who departed the world on the day I completed this project and whose wry humor and dignity throughout the twilight of his years embody the qualities back cover blurbs are always insisting I ought to find in Cormac McCarthy’s books. I would also like to thank friends who read drafts and housemates who tolerated my sometimes excessive monopolization of the kitchen table. Their days of eating breakfast amid unreasonable stacks of books have at long last come to a close. Dykstal 2 “Like their counterparts in northern cities, business leaders in the New South came to acknowledge the social disorder of their cities as regrettable byproducts of the very urban-industrial world they had championed. Drunkenness, prostitution, disease, poverty, crime, and political corruption were all understood as symptoms of the moral and physical chaos the lower classes fell into in the modern city….It was the instinctive reaction of the business class to respond with efforts to bring order to the urban world they inhabited.” —Don H. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

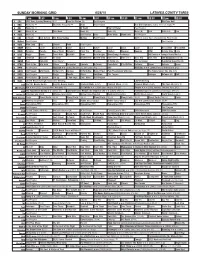

Sunday Morning Grid 6/28/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/28/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Red Bull Signature Series From Las Vegas. Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Vista L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Golf U.S. Senior Open Championship, Final Round. 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Bodyguard ›› (R) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Madison ›› (2001) Jim Caviezel, Jake Lloyd. -

TV Listings FRIDAY, JANUARY 6, 2017

TV listings FRIDAY, JANUARY 6, 2017 17:35 Miraculous Tales Of Ladybug 05:30 Henry Hugglemonster 13:15 Emmerdale And Cat Noir 05:45 Zou 13:45 Coronation Street 18:00 The Next Step 06:00 Art Attack 14:15 Masterpiece With Alan 18:25 Descendants Wicked World 06:30 Henry Hugglemonster Titchmarsh 18:30 Liv And Maddie 06:45 Loopdidoo 15:10 Alphabetical 18:55 Star Darlings 07:00 Zou 16:00 Midsomer Murders 00:20 Wheeler Dealers 07:15 Calimero 17:50 Black Work 19:00 Bunkʼd 06:00 Supa Strikas 01:10 Salvage Hunters 19:25 Disney Mickey Mouse 07:30 Loopdidoo 18:45 Emmerdale 02:00 Marooned With Ed Stafford 00:10 Hank Zipzer 06:25 Supa Strikas 00:35 Binny And The Ghost 19:30 Austin & Ally 07:45 Henry Hugglemonster 19:45 Coronation Street 02:50 Treasure Quest: Snake Island 08:00 Minnieʼs Bow-Toons 06:50 Counterfeit Cat 20:10 Alphabetical 03:40 Fat Nʼ Furious: Rolling Thunder 01:00 Violetta 19:55 Descendants Wicked World 07:00 Star vs The Forces Of Evil 01:45 The Hive 20:00 Backstage 08:05 PJ Masks 21:00 Midsomer Murders 04:30 The Liquidator 08:15 Goldie & Bear 07:15 K.C. Undercover 22:50 Emmerdale 05:00 How Do They Do It? 01:50 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 20:25 Tsum Tsum Shorts 07:40 Atomic Puppet Witch 20:30 Elena Of Avalor 08:30 Jake And The Never Land 05:30 How Do They Do It? Pirates 08:10 Lab Rats 06:00 Blue Collar Backers 02:15 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 20:55 Best Friends Whenever 08:35 Danger Mouse Witch 21:20 Jessie 08:45 Miles From Tomorrow 06:50 Mega Shippers 08:55 Sofia The First 09:00 Lab Rats: On The Edge 07:40 Impossible Engineering 02:40 -

The Southern Literary Influences of Cormac Mccarthy and How They

Brandeis University Waltham Massachusetts Department of English Myth, Legend, Dust: The Southern Literary Influences of Cormac McCarthy and How They Portend the Evening Redness in the West Benjamin Rui-Lin Fong Advisor: John Burt A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brandeis University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English May 2018 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor and mentor, the bardic John Burt, who was my first English professor at Brandeis and whose intellectual guidance and comments have helped shape every part of this thesis. Professor Burt’s Southern Literature course led to my first encounter with Blood Meridian. His lecture on Milton’s Satan and Judge Holden inspired this three-year obsession with Cormac McCarthy. I would like to thank Jerome Tharaud who has been a particularly inspirational professor and mentor whose guidance, enthusiasm, and instruction sparked my love for American literature. He has been particularly helpful in his advice on balancing thesis work and my applications to graduate school. I would like to thank Kurt Cavender who encouraged a UWS student to take more English classes (and who spent his own time to nominate me for an award). I would like to thank Pu Wang whose lectures on tragedy and modernity inspired me to pursue the Knoxville portions of this thesis. Lastly, I would like to thank Emma Smith. Our talks about Shakespeare have stayed in my mind, and Shakespeare’s language, stories, and characters come to mind every day. Finally, I would like to thank my family, whose love and support have spanned continents. -

Mccarthy Cormac

A Guide to the Cormac McCarthy Papers 1964-2007 Collection 091 Descriptive Summary Creator: Cormac McCarthy Title: The Cormac McCarthy Papers Dates: 1964-2007 Abstract: The Cormac McCarthy Papers span 1964-2007 and document the literary career of one of America’s most celebrated authors. The collection is arranged in two series: Published Works and Unpublished Works. The bulk of the collection is Published Works. Novels and produced plays and screenplays represented include: The Orchard Keeper; Outer Dark; Child of God; The Gardener’s Son; Suttree; Blood Meridian; All the Pretty Horses; The Crossing; The Stonemason; Cities of the Plain; No Country for Old Men; the Road; and The Sunset Limited. Unpublished Works include the screenplay, “Whales and Men,” and an unfinished novel “The Passenger.” NOTE: “The Passenger” is restricted until after novel is published. Identification: Collection 091 Extent: 98 boxes (46 linear feet) Language: English. Repository: Southwestern Writers Collection, The Wittliff Collections, Alkek Library, Texas State University-San Marcos Cormac McCarthy Papers SWWC Collection 091 Biographical Sketch Pulitzer Prize winning novelist and playwright, Cormac McCarthy, was born Charles McCarthy, Jr., on July 20, 1933, in Providence, Rhode Island. He was the third of six children born to Charles and Gladys McCarthy, preceded by sisters Jackie and Bobbie, and followed by Bill, Maryellen, and Dennis. In 1937, his parents moved the family to Knoxville, Tennessee, where his father was employed as a lawyer with the Tennessee Valley Authority. McCarthy spent much of his life in Tennessee, and his early works are clearly influenced by that region. His first four published novels, The Orchard Keeper (1965), Outer Dark (1968), Child of God (1973), and Suttree (1979), reflect the culture, myth and character of East Tennessee and Appalachia. -

Knoxville & Appalachia in the Works of Cormac Mccarthy

1 Knoxville & Appalachia In The Works Of Cormac McCarthy The publication of the newly crowned Pulitzer prize winner The Road in late 2006 marks an imaginative homecoming for Cormac McCarthy. On a literal level McCarthy has returned to the setting of his first four novels, and of course to his childhood home of Knoxville, East Tennessee and Appalachia. However, the acclaimed Border Trilogy and the 2005 novel No Country For Old Men are infused with the myths, culture, humor and indeed violence of his native soil, and Knoxville and Appalachia have consistently informed one of the most unique and challenging voices at work today in Southern and American fiction. The Road has very much bought McCarthy’s career full circle. Indeed, more than just signal an imaginative homecoming, the novel even suggests that the region affords an opportunity for regeneration and rebirth – those sacrosanct American myths – in a world where all other physical, cultural and spatial markers have quite simply been destroyed. In order to illuminate The Road and McCarthy’s southern body of work, I will provide some brief biographical information, as well as addressing the key themes and issues which we can find in his Southern novels. I would also like to incorporate the work of the southern literary scholar Richard Gray who, in his excellent study Southern Aberrations, asks important questions about the issues which inform the construction of Southern literary and cultural identity. Furthermore, I would also like to briefly consider the myth and history of Knoxville and East Tennessee, narrative modes which have done much to inform McCarthy’s work. -

ANALYSIS Outer Dark (1968) Cormac Mccarthy (1933- ) “In 1968

ANALYSIS Outer Dark (1968) Cormac McCarthy (1933- ) “In 1968 Random House published Outer Dark, again to generally strong reviews. Thomas Lask, in the New York Times, wrote, ‘Cormac McCarthy’s second novel, Outer Dark, combines the mythic and the actual in a perfectly executed work of the imagination. He has made the fabulous real, the ordinary mysterious. It is as if Elizabeth Madox Roberts’s The Time of Man, with its earthbound folkways and inarticulate people, had been mated with one of Isak Dineson’s gothic tales.’ Guy Davenport, in his New York Times Book Review article, also drew the connection to Dineson, adding, ‘Nor does Mr. McCarthy waste a single word on his characters’ thoughts. With total objectivity he describes what they do and records their speech. Such discipline comes not only from mastery over words but from an understanding wise enough and compassionate enough to dare to tell so abysmally dark a story.’ Walter Sullivan, another early supporter but also a consistently demanding critic of McCarthy, noted in Sewanee Review, ‘There is no way to overstate the power, the absolute literary virtuosity, with which McCarthy draws his scenes. He writes about the finite world with an accuracy so absolute that his characters give the impression of a universality which they have no right to claim…. It is the way of the good writer to find the universal in the particular, for finally it is the universal that he seeks. McCarthy, on the other hand, seems to love the singular for its own sake: he appears to seek out those devices and people and situations that will engage us by their very strangeness.’ He concluded, ‘There is no way to avoid grappling with the intractable reality that surrounds us.