RAS225 Proof 80..97

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CENTER for UNDERPRIVILEGED CHILDREN by Afreen Ahmed Rochana 12308003 ARC 512 SEMINAR II

SHAYAMBHAR: CENTER FOR UNDERPRIVILEGED CHILDREN By Afreen Ahmed Rochana 12308003 ARC 512 SEMINAR II Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Bachelor of Architecture Department of Architecture BRAC University Abstract: The word ―Underprivileged‖ refers to a group of people deprived through social and economic condition of some of the fundamental rights of all members of a civilized society. Our society can see many people who are totally deprived of most their basic rights due to poverty. If we think of the underprivileged children, they drop off their school only to run their families, whereas the other children of the same society who are well off are blessed to continue their education. Those underprivileged children have no other choice than leaving the school and work for the family to earn some money. Most of them want to continue their education but are helpless. Being children of a society where others can get the light of education, they do not deserve to be deprived of this basic need. My project ―Shayambhar‖ intends to give these underprivileged children the platform where they can receive education and at the same time help their families by doing some productive works. It is hoped that in future the children will be educated and at the same time they will become self-dependent. I believe that there will be a time when these children will be referred as an asset for the nation rather than a burden of society if they are given proper opportunities. Acknowledgement End of the journey of B.Arch. -

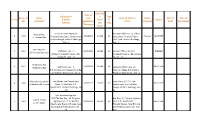

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr. -

Name of DDO/Hoo ADDRESS-1 ADDRESS CITY PIN SECTION REF

Name of DDO/HoO ADDRESS-1 ADDRESS CITY PIN SECTION REF. NO. BARCODE DATE THE SUPDT OF POLICE (ADMIN),SPL INTELLIGENCE COUNTER INSURGENCY FORCE ,W B,307,GARIA GROUP MAIN ROAD KOLKATA 700084 FUND IX/OUT/33 ew484941046in 12-11-2020 1 BENGAL GIRL'S BN- NCC 149 BLCK G NEW ALIPUR KOLKATA 0 0 KOLKATA 700053 FD XIV/D-325 ew460012316in 04-12-2020 2N BENAL. GIRLS BN. NCC 149, BLOCKG NEW ALIPORE KOL-53 0 NEW ALIPUR 700053 FD XIV/D-267 ew003044527in 27-11-2020 4 BENGAL TECH AIR SAQ NCC JADAVPUR LIMIVERSITY CAMPUS KOLKATA 0 0 KOLKATA 700032 FD XIV/D-313 ew460011823in 04-12-2020 4 BENGAL TECH.,AIR SQN.NCC JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY CAMPUS, KOLKATA 700036 FUND-VII/2019-20/OUT/468 EW460018693IN 26-11-2020 6 BENGAL BATTALION NCC DUTTAPARA ROAD 0 0 N.24 PGS 743235 FD XIV/D-249 ew020929090in 27-11-2020 A.C.J.M. KALYANI NADIA 0 NADIA 741235 FD XII/D-204 EW020931725IN 17-12-2020 A.O & D.D.O, DIR.OF MINES & MINERAL 4, CAMAC STREET,2ND FL., KOLKATA 700016 FUND-XIV/JAL/19-20/OUT/30 ew484927906in 14-10-2020 A.O & D.D.O, O/O THE DIST.CONTROLLER (F&S) KARNAJORA, RAIGANJ U/DINAJPUR 733130 FUDN-VII/19-20/OUT/649 EW020926425IN 23-12-2020 A.O & DDU. DIR.OF MINES & MINERALS, 4 CAMAC STREET,2ND FL., KOLKATA 700016 FUND-IV/2019-20/OUT/107 EW484937157IN 02-11-2020 STATISTICS, JT.ADMN.BULDS.,BLOCK-HC-7,SECTOR- A.O & E.O DY.SECY.,DEPTT.OF PLANNING & III, KOLKATA 700106 FUND-VII/2019-20/OUT/470 EW460018716IN 26-11-2020 A.O & EX-OFFICIO DY.SECY., P.W DEPTT. -

Swap an Das' Gupta Local Politics

SWAP AN DAS' GUPTA LOCAL POLITICS IN BENGAL; MIDNAPUR DISTRICT 1907-1934 Theses submitted in fulfillment of the Doctor of Philosophy degree, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1980, ProQuest Number: 11015890 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015890 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis studies the development and social character of Indian nationalism in the Midnapur district of Bengal* It begins by showing the Government of Bengal in 1907 in a deepening political crisis. The structural imbalances caused by the policy of active intervention in the localities could not be offset by the ’paternalistic* and personalised district administration. In Midnapur, the situation was compounded by the inability of government to secure its traditional political base based on zamindars. Real power in the countryside lay in the hands of petty landlords and intermediaries who consolidated their hold in the economic environment of growing commercialisation in agriculture. This was reinforced by a caste movement of the Mahishyas which injected the district with its own version of 'peasant-pride'. -

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 9 | 2014 Art of Bangladesh: the Changing Role of Tradition, Search for Identity and Gl

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 9 | 2014 Imagining Bangladesh: Contested Narratives Art of Bangladesh: the Changing Role of Tradition, Search for Identity and Globalization Lala Rukh Selim Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/samaj/3725 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.3725 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Lala Rukh Selim, “Art of Bangladesh: the Changing Role of Tradition, Search for Identity and Globalization”, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], 9 | 2014, Online since 22 July 2014, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/3725 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.3725 This text was automatically generated on 21 September 2021. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Art of Bangladesh: the Changing Role of Tradition, Search for Identity and Gl... 1 Art of Bangladesh: the Changing Role of Tradition, Search for Identity and Globalization Lala Rukh Selim Introduction 1 The art of Bangladesh embodies the social and political changes that have transformed the country/region through history. What was once a united state of Bengal is now divided into two parts, the sovereign country of Bangladesh and the state of West Bengal in India. The predominant religion in Bangladesh is Islam and that of West Bengal is Hinduism. Throughout history, ideas and identifications of certain elements of culture as ‘tradition’ have played an important role in the construction of notions of identity in this region, where multiple cultures continue to meet. The celebrated pedagogue, writer and artist K. -

Chapter - One: Agriculture and Allied Activities

Chapter - One: Agriculture and Allied Activities I. AGRICULTURE AND ALLIED ACTIVITIES A. Agriculture a) The target fixed by Govt. of India for agricultural growth at 4% for the State of West Bengal which is around 3.5% now. Considering the agro-climatic condition, infrastructure, resources etc. the projected foodgrains production growth rate has been revised and fixed at 4.5% during XIth plan period. Previously the average foodgrains productivity growth was calculated taking into account Xth plan average productivity and XIth plan projected average productivity and which was projected 5.91% i.e. around 6% and production growth was calculated considering the production of 2011-12 (The last year of XIth plan) and present level of production (which was around 160 lakh tonnes) which was around 15%. However, all the data are revised for Xlth plan period and the strategy for achieving new growth rate are sending for consideration along with revised target. The production of foodgrains will be increased due to increase of cropping intensity. b) Discussion on Food Security West Bengal is surplus in production of rice but there are deficits in the production of wheat and pulses. The requirement of foodgrains during 2006-07 was around 168.39 lakh M.T. and the production was 159.75 lakh M.T. The deficit was mainly due to less production of wheat and pulses. Keeping this in mind various state plan and Centrally Sponsored Scheme will be in operation during eleventh plan period. National Food Security Mission has been started across 12 districts of the State to boost up the production of wheat, pulses and rice. -

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

Basic Pay Date of Designation / Type Comp. Sl. Name First Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Pay in of Status No S/D/W/O Application D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address Pay Flat (Receving) Band Bhaskar Rao Senior Personal Assistant Accounts Officer & Ex- officio 1 1957 9/1/2013 14,260 B Transfer ALLOTTED Lt. Lachami Rao Finance (Audit) Deptt. Government Asstt. Secy. Fin (Ac/s) Deptt. of West Bengal, Writers' Buildings, W.B. Sectt. Writer's Buildings, Kol - 1 Kol - 1 Smt. Rita Dan 2 2022 Staff Nurse, Gr - II 16/1/2013 15,540 B Accouts Officer, Medical Allotted Sri Nirmalya Samanta Medical College & Hospital , 88, College & Hospital , 88, College College St. , Kol - 73 St., Kol - 73 Shelly Saha Roy 3 2031 17/1/2013 15,540 B ALLOTTED Ashim Saha Roy Staff Nurse, Gr. - II Accounts Officer, R.G. Kar R.G. Kar Medical College & Hospital Medical College & Hospital 1, 1, Khudiram Bose Sarani , Kol - 4 Khudiram Bose Sarani , Kol - 4 Manoj Kumar Jaiswar Law Officer, Law Department Asstt. Secy. & D.D.O. Law 4 2040 18/1/2013 15,600 B ALLOTTED Sri Ram Brichh Jaiswar Block - V, 2nd floor, P.E. Department Govt. of West Department. Writers' Buildings, Kol Bengal, Writers' Buildings, Kol - - 01 01 Sub- Assistant Engineer O/O The Exe. Eng., 24, Parganas Exe. Eng. 24 - Pargans Highway Tapash Sarkar 5 2043 Highway Divn., P.W. (Roads) 18/1/2013 14,610 B Divn. P.W. (Roads) Dte. , ALLOTTED Lt. Anil Sarkar Directorate, Bhavani Bhavan New Bhavani Bhavan, New Building Building (6th Floor) Alipore, Kol - (6th Flooor) Alipore, Kol - 700 27 027 Basic Pay Date of Designation / Type Comp. -

Doctor and Hospital List, Kolkata Consular District

Medical Facilities in Kolkata Consular District The following list of hospitals and physicians has been compiled by the American Consulate General, Kolkata. It is not meant to be a complete listing, as there are many competent doctors in the community. Retention on this list does not indicate continued competence but rather a lack of negative comment. The listing does not represent either a guarantee of competence or endorsement by the Department of State or by the American Consulate General in Kolkata. Dialing in India: The country code for India is 91. If you are calling within India, please omit the country code and replace with a ‘0’ for all numbers listed below. Contents Hospitals ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 Apollo Gleneagles Hospitals ...................................................................................................................... 4 B.M. Birla Heart Research Centre ............................................................................................................ 4 B.P. Poddar Hospital & Medical Research Ltd. ................................................................................... 4 Belle Vue Clinic .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Bhagirathi Neotia Woman & Child Care Centre ................................................................................ -

Are You a Resident of Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC)

PRESS NOTE Are you a resident of Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC)/ New Town Kolkata Development Authority (NKDA) area/Bidhannagar Municipal Corporation, and an expectant 2nd dose COVID vaccinee, who has taken the 1st dose in a private hospital and are now anxious about how to get the 2nd dose, as there are no vaccines available with them for you? If yes, did you know that you may walk into any government health facility of the KMC, NKDA or BMC for getting your 2nd dose, free of cost? However, if your 2nd dose is overdue (>56 days from first dose of Covidshield or >42 days for Covaxin),then just walk into the facilities mentioned (list given). You shall be administered the second dose. For your greater convenience, the government has tagged each private hospital with a government health facility (please see list given) which you can walk into and get your 2nd dose. For example, if you have taken your 1st dose in AMRI Dhakuria, then you should ideally visit the government health facility which is tagged to AMRI Dhakuria i.e., KMC Urban Primary Health Centre - 87 for Covishield and KMC Urban Primary Health Centre - 90 for Covaxin. You can also visit any of the major Government hospitals given in the list for taking your 2ndvaccine dose in a similar walk-in manner, and get yourself vaccinated for free. For vaccination at the said government facilities, please carry one of your photo identification documents like Voter ID/Aadhaar/Passport/PAN Card etc. along with a proof of your first dose of vaccine received (i.e the SMS which you had received on receipt of first dose) The State Government is working to evolve a more precise and convenient information dissemination system for the benefit of all intending COVID vaccines. -

Paper 22 SOCIO-CULTURAL and ECONOMIC HISTORY OF

DDCE/M.A Hist./Paper-22 SOCIO-CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC HISTORY OF MODERN INDIA By Dr.Ganeswar Nayak Lecturer in History SKCG College Paralakhemundi s1 PAPER-22 SOCIO CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC HISTORY OF MODERN INDIA. INTRODUCTION (BLOCK) During the 17th and 18th century, India maintained a favorable balance of trade and had a steady economy .Self-sufficient agriculture, flourishing trade and rich handicraft industries were hallmark of Indian economy. During the last half of the 18thcentury, India was conquered by the East India Company. Along with the consolidation of British political hegemony in India, there followed colonization of its economy and society. Colonization no longer functioned through the crude tools of plunder and tribute and mercantilism but perpetuated through the more disguised and complex mechanism of free trade and foreign capital investment. The characteristic of 19th century colonialism lay in the conversion of India into supplier of foodstuff and raw materials to the metropolis, a market for metropolitan manufacturer, and a field for investment of British capital. In the same way, Indian society in the 19th century was caught in a inhuman web created by religious superstition and social obscuration .Hinduism, has became a compound of magic, animation and superstition and monstrous rites like animal sacrifice and physical torture had replaced the worship of God.The most painful was position of women .The British conquest and dissemination colonial culture and ideology led to introspection about the strength and weakness of indigenous culture and civilization. The paper discusses the Socio –Cultural and Economic history of modern India. Unit –I, discusses attitude and understandings of Orientalist, Utilitarian and Evangelicals towards Indian Society .It further delineates the part played by Christian Missionaries in India.The growth of press and education analyzed in the last section. -

Representation of European Dress in Indigenous Art of Bengal Surajit Chanda Assistant Prof

Pratidhwani the Echo A Peer-Reviewed International Journal of Humanities & Social Science ISSN: 2278-5264 (Online) 2321-9319 (Print) Impact Factor: 6.28 (Index Copernicus International) UGC Approved, Journal No: 48666 Volume-VII, Issue-IV, April 2019, Page No. 232-248 Published by Dept. of Bengali, Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam, India Website: http://www.thecho.in Representation of European dress in indigenous Art of Bengal Surajit Chanda Assistant Prof. (Sr. Gr) Applied Art Dept. Faculty of Visual Arts Rabindra Bharati, Kolkata Abstract The earliest European nation that settled in Bengal was the Portuguese in 1518 C.E. During 1538 C.E. the Portuguese build their factories and settlements at Saptagram, Chittagong and finally Hooghly. From 1615C.E. onwards, the Dutch East India Company started trading activities in lower part of Bengal. The British, the French, the Danes, the Flemish and other formed their settlements in Bengal later. Social exchange between the European powers and local people continued from the beginning mainly for trading. Finally after the British became administrative head of the country; their influence became widespread in all aspects of the life of local indigenous people especially artistic activities, and costumes. Representation of Europeans in different forms of local Art largely found during this period. The impact of these foreign cultures is found in different forms of contemporary indigenous Art like Pata-paintings, wood-carvings, metal engravings, temple terracotta plaques, Provincial Mughal school of paintings, Company painting (drawn by Indian artist), Bat- tala print, Kantha (Stitched Quilts), dolls, toys metal engravings on ‘Ratha’, Book Illustration and other. The representation of European dress and costumes as seen through the eyes of local people of Bengal from 17th century C.E. -

Mapping a Liminal: Nurturing of Kantha Into Contemporary Art

MAPPING A LIMINAL: NURTURING OF KANTHA INTO CONTEMPORARY ART. Natasha Narain Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) Kala Bhawan, Viswa Bharati University, India. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology, Australia. 2017 3 Keywords • Automatic drawing, catharsis, connection, conflict, complex and hybrid identity, goddesses, interdisciplinary, kantha, material culture, memory, making a place, painting, portability, reconfigure, reflexive, reparation, restitution, sacred, South Asia, touch, transnational feminism, transcultural, tradition, textile, transformation. 4 Abstract Kantha emerged as an embroidery and textile-based personal storytelling craft, anchored in women's experiences in undivided Bengal. Historical events and the increased complexities of a globalised world have altered the nature of kantha. This research examines different approaches that revitalise this tradition in contemporary practice. My project set out to discover how the conceptual and formal strategy of kantha could be reinterpreted through contemporary art in a way that acknowledges history and the trauma and loss involved. It does this through creative practice where kantha techniques are applied to different media and presented as a contemporary art installation, to reveal how a polyphonous reconnection with the past may be possible. This creative research is then contextualised within the practices of a number of contemporary artists who have integrated local and/or culturally specific motifs, metaphors, media and techniques into their art practices as a way to consider broader humanitarian issues and themes of cultural and environmental loss as seen through the lens of personal experience. What I discovered is that rather than simply providing a replication of kantha, this approach offers a self-reflexive solution that permits hybridised cultural complexity and a portable method of making place.