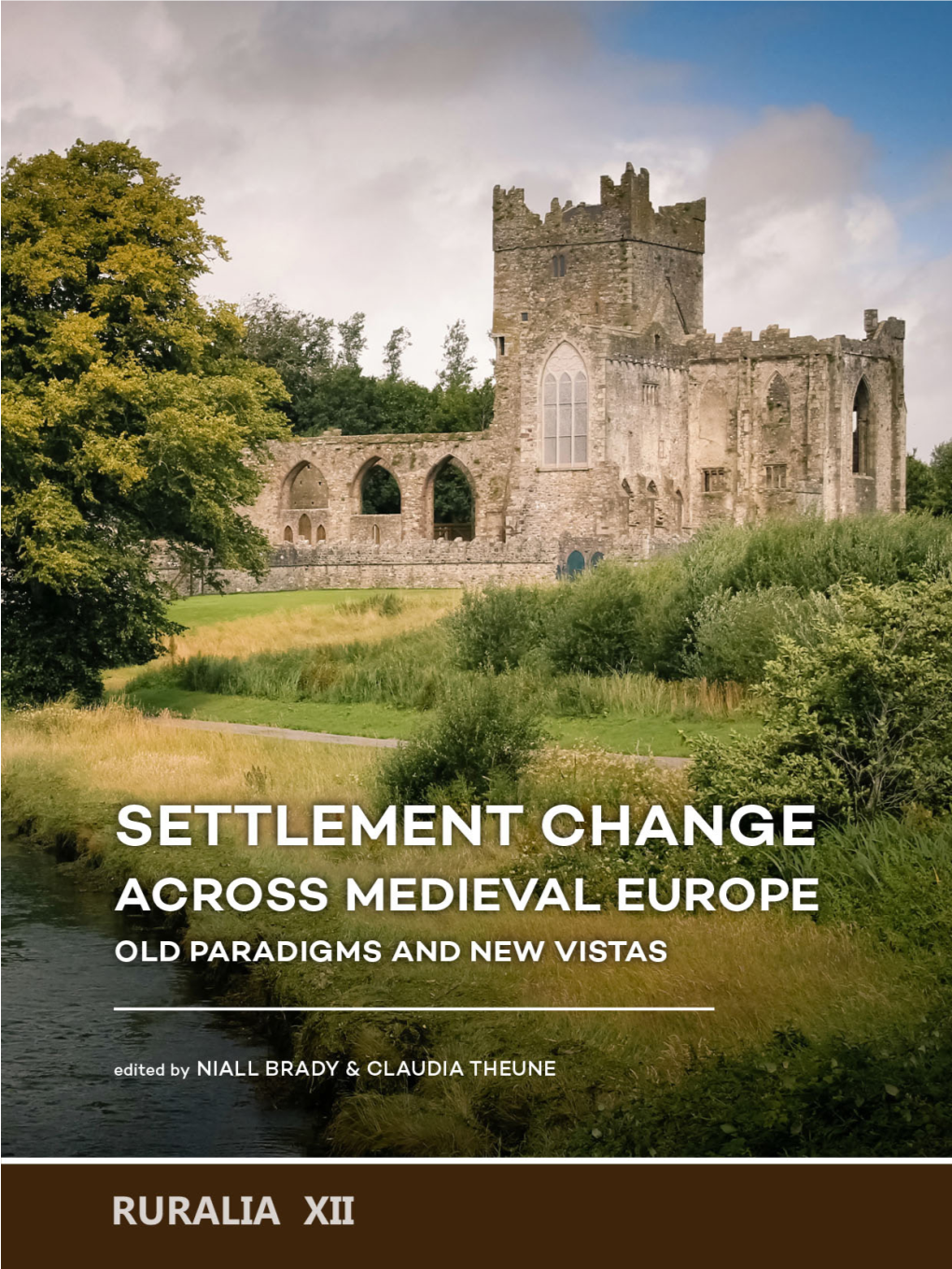

Settlement Change Across Medieval Europe Old Paradigms and New Vistas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Athenian Agora

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 12 Prepared by Dorothy Burr Thompson Produced by The Stinehour Press, Lunenburg, Vermont American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1993 ISBN 87661-635-x EXCAVATIONS OF THE ATHENIAN AGORA PICTURE BOOKS I. Pots and Pans of Classical Athens (1959) 2. The Stoa ofAttalos II in Athens (revised 1992) 3. Miniature Sculpturefrom the Athenian Agora (1959) 4. The Athenian Citizen (revised 1987) 5. Ancient Portraitsfrom the Athenian Agora (1963) 6. Amphoras and the Ancient Wine Trade (revised 1979) 7. The Middle Ages in the Athenian Agora (1961) 8. Garden Lore of Ancient Athens (1963) 9. Lampsfrom the Athenian Agora (1964) 10. Inscriptionsfrom the Athenian Agora (1966) I I. Waterworks in the Athenian Agora (1968) 12. An Ancient Shopping Center: The Athenian Agora (revised 1993) I 3. Early Burialsfrom the Agora Cemeteries (I 973) 14. Graffiti in the Athenian Agora (revised 1988) I 5. Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora (1975) 16. The Athenian Agora: A Short Guide (revised 1986) French, German, and Greek editions 17. Socrates in the Agora (1978) 18. Mediaeval and Modern Coins in the Athenian Agora (1978) 19. Gods and Heroes in the Athenian Agora (1980) 20. Bronzeworkers in the Athenian Agora (1982) 21. Ancient Athenian Building Methods (1984) 22. Birds ofthe Athenian Agora (1985) These booklets are obtainable from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens c/o Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J. 08540, U.S.A They are also available in the Agora Museum, Stoa of Attalos, Athens Cover: Slaves carrying a Spitted Cake from Market. -

The Aksumites in South Arabia: an African Diaspora of Late Antiquity

Chapter 11 The Aksumites in South Arabia: An African Diaspora of Late Antiquity George Hatke 1 Introduction Much has been written over the years about foreign, specifically western, colo- nialism in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as about the foreign peoples, western and non-western alike, who have settled in sub-Saharan Africa during the modern period. However, although many large-scale states rose and fell in sub- Saharan Africa throughout pre-colonial times, the history of African imperial expansion into non-African lands is to a large degree the history of Egyptian invasions of Syria-Palestine during Pharaonic and Ptolemaic times, Carthagin- ian (effectively Phoenician) expansion into Sicily and Spain in the second half of the first millennium b.c.e, and the Almoravid and Almohad invasions of the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. However, none of this history involved sub-Saharan Africans to any appreciable degree. Yet during Late Antiquity,1 Aksum, a sub-Saharan African kingdom based in the northern Ethi- opian highlands, invaded its neighbors across the Red Sea on several occasions. Aksum, named after its capital city, was during this time an active participant in the long-distance sea trade linking the Mediterranean with India via the Red Sea. It was a literate kingdom with a tradition of monumental art and ar- chitecture and already a long history of contact with South Arabia. The history of Aksumite expansion into, and settlement in, South Arabia can be divided into two main periods. The first lasts from the late 2nd to the late 3rd century 1 Although there is disagreement among scholars as to the chronological limits of “Late Antiq- uity”—itself a modern concept—the term is, for the purposes of the present study, used to refer to the period from ca. -

Baekje's Relationship with Japan in the 6Th Century G G G PARK, Hyun-Sook* G G Introduction

International Journal of Korean History(Vol.11, Dec. 2007) 97 G G G Baekje's Relationship with Japan in the 6th Century G G G PARK, Hyun-Sook* G G Introduction The goal of the present study is to elucidate the nature of foreign relations between Baekje (ᓏ᱕) and Japan's Yamato regime in the 6th century. The relations between Korea and Japan in the 6th century is recorded extensively in ØNihon Shoki (ᬝᔲᙠᄀ)Ù. Although Japan had relations with several countries in Korea, the focus of the book is heavily placed on Baekje. Therefore, unveiling the nature of foreign relations between Baekje and the Yamato regime of Japan in the 6th century is important to determine the actual situation of Korea-Japan relations in ancient times. One major theme in research trends1 concerning the relations between 6th century Baekje and Japan's Yamato regime is the continuity found between the ‘Imna-Ilbon Bu (ᬢᄧᬝᔲᕒ)’ of the “Wai (ᦖ)” after the 4th century and the tributary foreign relation policy of Baekje. Conversely, in Korea, a mutually beneficial relationship existed between Baekje and Japan Baekje provided advanced cultural resources and Japan provided military power. Thus, the mutual understanding based on tactical foreign relation policy2 defined the relations between these two countries. In this GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG * Professor, Department of History Education, Korea University. 98 Baekje's Relationship with Japan in the 6th Century light, studies of Korean and Japan relations were not able to clarify reality due to the understanding of others through their own perspectives. Basically, the standpoint of Japanese historians has centered on the Yamato regime and on its dynamical relations with the Three Kingdoms of the Korean peninsula. -

Impact of the 536/540 CE Double Volcanic Eruption Event on the 6Th-7Th Century Climate Using Model and Proxy Data

Impact of the 536/540 CE double volcanic eruption event on the 6th-7th century climate using model and proxy data Evelien van Dijk Claudia Timmreck, Johann Jungclaus, Stephan Lorenz, Manon Bajard, Josh Bostic and Kirstin Krüger EGU 2020, session CL1.18: Studying the climate of the last two millennia [email protected] https://www.mn.uio.no/geo/english/research/projects/vikings/ Motivation and Background ● Volcanic eruptions are important climate drivers (Crowley et al., 2000; Robock 2000) ● Very cold period after the 536/540 CE double eruption event in the mid-6th century (Larsen et al., 2008; Sigl et al., 2015) ● Evidence from multiple tree-ring records for a centennial cooling up to 660 CE (Büntgen et al., 2016) ● Previous MPI-ESM simulations show a decrease in surface temperature and an increase in Arctic sea-ice up to 15 years (Toohey et al., 2016) Research question: Can we force a century long lasting cooling due to major volcanic eruptions in the 6th-7th century in earth system models? van Dijk et al., in prep. 2 © E. van Dijk . All rights reserved Model experiment and set-up MPI-ESM-LR1.2 version for CMIP6/PMIP4 (Mauritsen et al., 2019) ECHAM6: T63 → 200x200 km, 47 vertical levels, top @ 80km MPIOM: GR1.5 → 150x150 km, 40 vertical levels ● 10 x 160 years → 520-680 CE Eruption Eruption S Peak Latitude year CE month injected aerosol of ● spin up from PMIP4/Past2k run optical eruption depth in ● PMIP4 volcanic forcing model (Toohey and Sigl 2017, Jungclaus et al., 2017) 536 Jan 18.8 Tg 0.5 NHext (~45N) ● Anomalies calculated wrt 0- 540 Jan 31.8 Tg 0.7 Tropical 1850 CE (Past2k run) (~15N) 574 Jan 24.2 Tg 0.6 Tropical 626 Jan 13.2 Tg 0.4 NHext *Toohey and Sigl (2017): eVolv2k, based on ice-core records + Easy Volcanic Aerosol model + scaling factor (Gao et al. -

IV in Ravenna-Classe, Lower-Class Apartments in the Harbor Area of The

38 IV Why do 5th/6th c. Ostrogothic elites continue to live in Roman-style elite houses of the 2nd/3rd c. Severan period? In Ravenna-Classe, lower-class apartments in the harbor area of the 1st century AD were excavated. Since this date does not prove the great importance of the town in the 5th/6th century, a small miracle has to be created. This miracle consists of a boldly postulated durability for apartments that last for more than half a millennium. With this move, one elegantly bridges the centuries, of which, as shown, Andrea Agnellus has not yet known anything (see above, Chapter I). In Ravenna proper, where the upper class is concentrated, one imagines to be on firmer ground. A magnificent find from 1993 appears to supports this view. The aristocratic Domus dei Tappeti di Pietra (Domus of the Stone Carpets) is one of the most important LEFT: Standardized 1st/2nd century Roman domus (city mansion). [https://pl.pinterest.com/pin/91057223699970657/.] RIGHT: Reconstruction of a section of the DOMUS DEI TAPPETI DI PIETRA in Ravenna (Domus of Stone Carpets; bedrooms are upstairs). The shapes of windows and doors are speculation. It is dated to the 5th/6th century but built like a lavish 2nd century city mansion (domus) with 700 m2 of mosaics in 2nd century style. [https://www.ravennantica.it/en/domus-dei-tappeti-di-pietra-ra/.] 39 Italian archaeological sites discovered in recent decades. Located inside the eighteenth-century Church of Santa Eufemia, in a vast underground environment located about 3 meters below street level, it consists of 14 rooms paved with polychrome mosaics and marble belonging to a private building of the fifth-sixth century. -

AD 536 the Sun Dimmed and Global Temperatures Plunged, Leading to Famine, Plague and the Collapse of Empires

“ The sun began to be darkened by day and the moon by night, while the ocean was tumultuous with spray from the 24th of March in this year till the 24th of June in the following year… And, as the winter was a severe one, so much so that from the large and unwonted quantity of snow the birds perished… there was distress… among men… from the evil things” ZACHARIAS OF MYTILENE (Chronicle, 9.19, 10.1) The year of darkness In AD 536 the sun dimmed and global temperatures plunged, leading to famine, plague and the collapse of empires. At last clues are emerging about the cause of this event, as Colin Barras reports 34 | NewScientist | 18 January 2014 EBvb^ofp>A203)^ka?vw^kqfkb efpqlof^kMol`lmfrplc@^bp^ob^e^pgrpq T^oofsbafkplrqebokFq^iv+Qeb_^i^k`blc mltbofkqebJbafqboo^kb^kfpfkciru7S^ka^ip e^ap^`hbaOljbfk122^kaqebTbpqbok Olj^kBjmfobe^ac^iibkfk143+Grpqfkf^kF) qeb?vw^kqfkb%loB^pqbokOlj^k&Bjmbolo) fpabqbojfkbaqlob`i^fjqebilpqqboofqlofbp+ >cqbo^pr``bppcri`^jm^fdk^d^fkpqqebKloqe >cof`^kS^ka^iHfkdaljfkqebb^oiv20-p) Grpqfkf^kafpm^q`ebpefp^ojvqlobq^hbFq^iv+ Vbq^pMol`lmfrpob`loap)pljbqefkdlaa qebke^mmbkba+Qebprkafjjba)^kaqeb afjkbppi^pqbaclojlobqe^k^vb^o+Qebob tbobcolpqp^kapkltpfkqebjfaaiblc prjjboÌqebtfkqbokbsboob^iivbkaba+Colj Fq^ivqlFobi^ka)@efk^ql@bkqo^i>jbof`^)qeb vb^o203t^pqeb_bdfkkfkdlc^ab`^ab*ilkd `liapk^m_bpbq_vqrojlfi+Obifdflkpilpq _bifbsbop)`fqfbp`lii^mpba^kalkblcqeb dob^qbpqmi^drbpfkefpqlovhfiiba^nr^oqbo lcqebmlmri^qflkfkqeb?vw^kqfkbBjmfob+ Grpqfkf^kÑp^ojfbpafaj^k^dbqlobq^hbOljb) _rqefptb^hbkbabjmfobt^plsbopqobq`eba) ^kapllkilpqqebqboofqlov^d^fk+ -

Explosive Eruption of El Chichón Volcano (Mexico) Disrupted 6Th Century Maya Civilization and Contributed to Global Cooling

Explosive eruption of El Chichón volcano (Mexico) disrupted 6th century Maya civilization and contributed to global cooling Kees Nooren1*, Wim Z. Hoek1, Hans van der Plicht2, Michael Sigl3, Manfred J. van Bergen1, Didier Galop4, Nuria Torrescano-Valle5, Gerald Islebe5, Annika Huizinga1, Tim Winkels1, and Hans Middelkoop1 1Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, 3508 TC Utrecht, Netherlands 2Center for Isotope Research, Groningen University, 9747 AG Groningen, Netherlands 3Laboratory of Environmental Chemistry, Paul Scherrer Institut, 5232 Villigen, Switzerland 4GEODE, Université Jean Jaurès, CNRS, UMR 5602, 31058 Toulouse, France 5Unidad Chetumal Herbario, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Chetumal, AP 424 Quintana Roo, Mexico ABSTRACT Gill, 2000; Nooren et al., 2009), and Ilopango A remarkably long period of Northern Hemispheric cooling in the 6th century CE, which (El Salvador; Oppenheimer, 2011), although disrupted human societies across large parts of the globe, has been attributed to volcanic Rabaul has recently been discarded (McKee forcing of climate. A major tropical eruption in 540 CE is thought to have played a key et al., 2015). Here, we present evidence for El role, but there is no consensus about the source volcano to date. Here, we present evidence Chichón (17.36°N, 93.23°W) in southern Mex- for El Chichón in southern Mexico as the most likely candidate, based on a refined recon- ico (Fig. 1) as the most likely candidate. struction of the volcano’s eruption history. A new chronological framework, derived from El Chichón has had multiple explosive erup- distal tephra deposits and the world’s largest Holocene beach ridge plain along the Gulf tions during the Holocene, some of them prob- of Mexico, enabled us to positively link a major explosive event to a prominent volcanic ably several times larger than the well-known sulfur spike in bipolar ice core records, dated at 540 CE. -

The Justinianic Plague: an Inconsequential Pandemic?

The Justinianic Plague: An inconsequential pandemic? Lee Mordechaia,b,1, Merle Eisenberga,c, Timothy P. Newfieldd,e, Adam Izdebskif,g, Janet E. Kayh, and Hendrik Poinari,j,k,l aNational Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center, Annapolis, MD 21401; bHistory Department, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mount Scopus, 9190501 Jerusalem, Israel; cHistory Department, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544; dHistory Department, Georgetown University, NW, Washington, DC 20057; eBiology Department, Georgetown University, NW, Washington, DC 20057; fPaleo-Science & History Independent Research Group, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, 07745 Jena, Germany; gInstitute of History, Jagiellonian University, 31-007 Kraków, Poland; hSociety of Fellows in the Liberal Arts, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544; iDepartment of Anthropology, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4L9, Canada; jDepartment of Biochemistry, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4L9, Canada; kMcMaster Ancient DNA Centre, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4L9, Canada; and lMichael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4L9, Canada Edited by Noel Lenski, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Elsa M. Redmond October 7, 2019 (received for review March 4, 2019) Existing mortality estimates assert that the Justinianic Plague tiquity (e.g., refs. 5 and 6). Yet this narrative overlooks the fact (circa 541 to 750 CE) caused tens of millions of deaths throughout that the political structures of the Western Empire had already the Mediterranean world and Europe, helping to end antiquity collapsed in the 5th century and the Eastern Empire did not de- and start the Middle Ages. In this article, we argue that this cline politically until the 7th century (18, 19). -

Political History from 6Th Century A. D. to 9Th Century A. D. the Territories

C H A P T E R II Political History from 6th Century A. D. to 9th Century A. D. The territories of early Bengal became an integral part of the Gupta empire. But it would not be proper to say that the people of Bengal submitted to the mighty Gupta emperors rather meekly. At least, we have one instance to show that the people of Bengal rose like one man and gave stiff resistence to the invading forces under King Chandra, though ultimately they were beaten. In view of the inevitable chaos that followed the dismemberment of the Gupta empire, the people of Bengal for the first time emerged into the limelight of political history of India and curved out independent principalities. The downfall of the Guptas marked the breaking up of northern India into a number of small states. Saurast racame under the domination of the Haitrakas of Valavi. Thane§_vara was taken over by the Pushyabhut is, while the Haukhauris held sway in Kanauj. y£sodharman, a military adventurer, attempted to set up an ephemeral empire in central India, Rajputana and other parts of the Punjab 1• 17 Magadha and Mal wa pas sed under the sway of the Later Guptas who ~ay have been an offshoot of the Imperial Guptas, but as yet we have no positive evidence in support of this view. Bengal also took advantage of the political situation tc shake off the foreign yoke and two powerful independent Kingdoms, viz. Vanga and Gauda were established there in the siXth and seventh • 2 Century A. -

Justinian's Provincial Reforms of the AD 530S

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2015 The Struggle Between the Center and the Periphery: Justinian's Provincial Reforms of the A.D. 530s Mark-Anthony Karantabias University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Karantabias, Mark-Anthony, "The Struggle Between the Center and the Periphery: Justinian's Provincial Reforms of the A.D. 530s" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--History. 31. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/31 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Some Hypothetical Evolutionary Lines Relating to the Phocean Red Slip

PYRENAE, vol. 50 núm. 2 (2019) ISSN: 0079-8215 EISSN: 2339-9171 (p. 133-150) © José Carlos Quaresma, 2019 – CC BY-NC-ND REVISTA DE PREHISTÒRIA I ANTIGUITAT DE LA MEDITERRÀNIA OCCIDENTAL JOURNAL OF WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN PREHISTORY AND ANTIQUITY DOI: 10.1344/Pyrenae2019.vol50num2.6 Some hypothetical evolutionary lines relating to the Phocean Red Slip Ware types 3F/G, 3G and 3/10 Algunas líneas hipotéticas de la evolución de la Terra Sigillata Focense Tardía, tipos 3F/G, 3G y 3/10 JOSÉ CARLOS QUARESMA Universidade Nova de Lisboa. Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Instituto de Estudos Medievais – FCSH/UNL Avenida de Berna, 26-C, P-1069-061 Lisboa [email protected] This paper discusses the typological evolution of Phocean Red Slip Ware (LRC) forms during the central decades of the 6th century AD, with regard to the evolution from type Hayes 3F into types 3G and 3/10, before the arrival of the latest shape (form Hayes 10) in the second half/late 6th century AD. Published and unpublished stratigraphic data from several regions of the Late Antique world, both in the Mediterranean and Atlantic are observed and three hypothetical evolutionary lines, in terms of their chronology and morphology, are discussed as a possible tool for further research on the subject. KEYWORDS PHOCEAN RED SLIP, FORMS HAYES 3 AND 10, CHRONO-STRATIGRAPHY, CENTRAL DECADES OF THE 6TH CENTURY, MEDITERRANEAN AND ATLANTIC Este artículo discute la evolución tipológica de las formas de la terra sigillata focense tardía (LRC), durante las décadas centrales del siglo VI, en particular los tipos Hayes 3F, 3G y 3/10, antes de la llegada de la morfología tardía Hayes 10 en la segunda mitad-finales del siglo VI. -

UNIT 4 POLITIES from 3Rd CENTURY A.D. TO

rd rd Polities from 3 Century UNIT 4 POLITIES FROM 3 CENTURY A.D. A.D. to 6th Century A. D. TO 6th CENTURY A.D. Structure 4.1. Introduction 4.2. The Rise of Gupta Power 4.3 The Gana-Sangha “Tribal” Polities 4.3.1 Yaudheyas and Malavas 4.3.2 Sanakanikas 4.4 Monarchical Set-up: Samatata and Kamarupa 4.5 Forest Chiefs 4.6 Nature of State under the Guptas 4.7 Rise of Feudatories and Disintegration of Gupta Empire 4.8 Nature of Polities and their Social Origins in South India: Evidence of Puranic and Epigraphic Sources 4.9 Historical Geography of Peninsular India 4.9.1 The Andhra Region 4.9.2 Karnataka 4.9.3 Maharashtra and North Karnataka 4.9.4 The Tamil Region 4.10 General Remarks on the Historical Geography of Peninsular India 4.11 Summary 4.12 Glossary 4.13 Exercises 4.1 INTRODUCTION The Indian sub-continent witnessed a prolonged flux in the post- Mauryan period with no major territorial organisation or major political power exercising control over large territories like that of the Mauryas (who were indigenous) or Kushanas, the latter being of central Asian origin. The Guptas were the first indigenous ruling family after the Mauryas to emerge as a powerful dynasty with a large territorial base in north India from the fourth to the sixth centuries AD. They were also the first major dynasty to have recorded their ventures (the Allahabad Pillar Inscription of Samudra Gupta) into south India as invaders raiding the eastern regions of the peninsula right down to the southern extremity of Andhra, encountering rulers like Hastivarman of Vengi (Salankayana) and Visnugopa of Kanci (Pallava) probably establishing a line of control meant to be a show of their prowess and dominance in a changing socio-political scene.