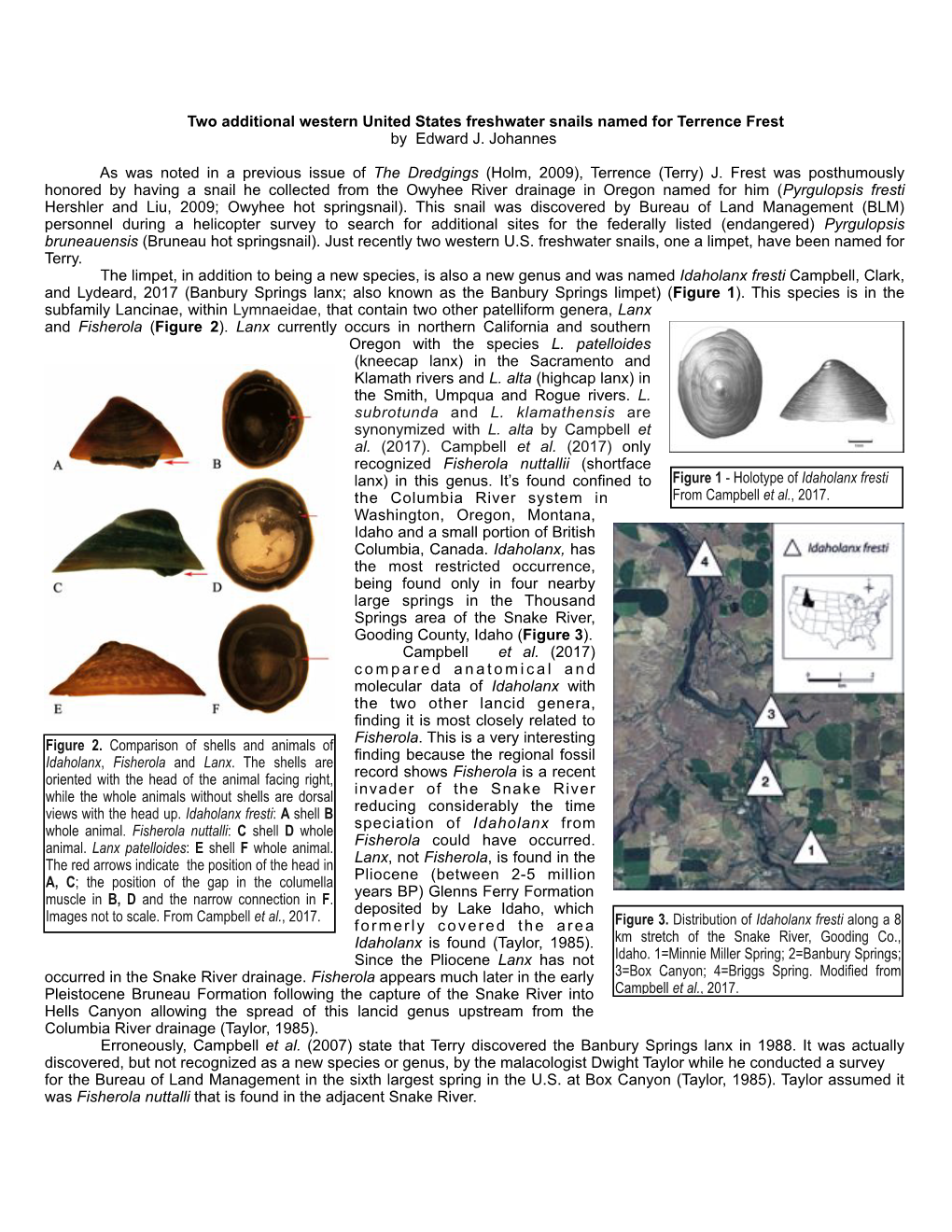

Two Additional Western United States Freshwater Snails Named for Terrence Frest by Edward J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Contribution to Distribution of Genus Stagnicola and Catascopia (Gastropoda: Lymnaeidae) in the Czech Republic

Malacologica Bohemoslovaca (2008), 7: 70–73 ISSN 1336-6939 A contribution to distribution of genus Stagnicola and Catascopia (Gastropoda: Lymnaeidae) in the Czech Republic LUBOŠ BERAN Kokořínsko Protected Landscape Area Administration, Česká 149, CZ-27601 Mělník, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected] BERAN L., 2008: A contribution to distribution of genus Stagnicola and Catascopia (Gastropoda: Lymnaeidae) in the Czech Republic. – Malacologica Bohemoslovaca, 7: 70–73. Online serial at <http://mollusca.sav.sk> 16-Sep-2008. This paper brings a contribution to the distribution of genus Stagnicola Jeffreys, 1830 and Catascopia Meier- Brook & Bargues, 2002 in the Czech Republic. Occurrence of four species has been confirmed in the Czech Republic so far. Two species – Stagnicola corvus (Gmelin, 1791) and S. palustris (O.F. Müller, 1774) (including S. turricula (Held, 1836)), are widespread and common especially in lowlands along bigger rivers (Labe, Ohře, Morava, Dyje, Odra). Occurrence of S. fuscus (Pfeiffer, 1821) is restricted to the territory of the north-western part of Bohemia and Catascopia occulta (Jackiewicz, 1959) is a rare species with only two known sites. Key words: Mollusca, Gastropoda, Stagnicola, Catascopia, distribution Introduction Material and methods Genus Stagnicola Jeffreys, 1830 comprises gastropods of The data used in this study are from the author’s database medium size, with gradually increasing whorls and anthra- of over 45.000 records of aquatic molluscs, most of which cite black pigmentation of their conchs. Only one species, were obtained by field research during the previous 10 Stagnicola palustris (O.F. Müller, 1774), was accepted years. The remainder comes from Czech museum colle- 1959. -

Taxonomic Status of Stagnicola Palustris (O

Folia Malacol. 23(1): 3–18 http://dx.doi.org/10.12657/folmal.023.003 TAXONOMIC STATUS OF STAGNICOLA PALUSTRIS (O. F. MÜLLER, 1774) AND S. TURRICULA (HELD, 1836) (GASTROPODA: PULMONATA: LYMNAEIDAE) IN VIEW OF NEW MOLECULAR AND CHOROLOGICAL DATA Joanna Romana Pieńkowska1, eliza Rybska2, Justyna banasiak1, maRia wesołowska1, andRzeJ lesicki1 1Department of Cell Biology, Institute of Experimental Biology, Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Umultowska 89, 61-614 Poznań, Poland (e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]) 2Nature Education and Conservation, Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Umultowska 89, 61-614 Poznań, Poland ([email protected], [email protected]) abstRact: Analyses of nucleotide sequences of 5’- and 3’- ends of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (5’COI, 3’COI) and fragments of internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) of nuclear rDNA gene confirmed the status of Stagnicola corvus (Gmelin), Lymnaea stagnalis L. and Ladislavella terebra (Westerlund) as separate species. The same results showed that Stagnicola palustris (O. F. Müll.) and S. turricula (Held) could also be treated as separate species, but compared to the aforementioned lymnaeids, the differences in the analysed sequences between them were much smaller, although clearly recognisable. In each case they were also larger than the differences between these molecular features of specimens from different localities of S. palustris or S. turricula. New data on the distribution of S. palustris and S. turricula in Poland showed – in contrast to the earlier reports – that their ranges overlapped. This sympatric distribution together with the small but clearly marked differences in molecular features as well as with differences in the male genitalia between S. -

Molecular Characterization of Liver Fluke Intermediate Host Lymnaeids

Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 17 (2019) 100318 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vprsr Original Article Molecular characterization of liver fluke intermediate host lymnaeids (Gastropoda: Pulmonata) snails from selected regions of Okavango Delta of T Botswana, KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga provinces of South Africa ⁎ Mokgadi P. Malatji , Jennifer Lamb, Samson Mukaratirwa School of Life Sciences, College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville Campus, Durban 4001, South Africa ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Lymnaeidae snail species are known to be intermediate hosts of human and livestock helminths parasites, Lymnaeidae especially Fasciola species. Identification of these species and their geographical distribution is important to ITS-2 better understand the epidemiology of the disease. Significant diversity has been observed in the shell mor- Okavango delta (OKD) phology of snails from the Lymnaeidae family and the systematics within this family is still unclear, especially KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) province when the anatomical traits among various species have been found to be homogeneous. Although there are Mpumalanga province records of lymnaeid species of southern Africa based on shell morphology and controversial anatomical traits, there is paucity of information on the molecular identification and phylogenetic relationships of the different taxa. Therefore, this study aimed at identifying populations of Lymnaeidae snails from selected sites of the Okavango Delta (OKD) in Botswana, and sites located in the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and Mpumalanga (MP) provinces of South Africa using molecular techniques. Lymnaeidae snails were collected from 8 locations from the Okavango delta in Botswana, 9 from KZN and one from MP provinces and were identified based on phy- logenetic analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS-2). -

Species Fact Sheet for Lanx Klamathensis

SPECIES FACT SHEET Scientific Name: Lanx klamathensis Hannibal 1912 Common Name: scale lanx Phylum: Mollusca Class: Gastropoda Order: Basommatophora Family: Lymnaeidae Conservation Status: Global Status: G1 (June 2000) National Status: United States (N1) (June 2000) State Statuses: Oregon (S1), California (S1) (NatureServe 2015) IUCN Red List: NE – Not evaluated Technical Description: The scale lanx was previously described as belonging to the family Ancylidae due to its limpet-like shell (ancylid species have shells that resemble low flat cones); however, subsequent authors have placed it in the family Lymnaeidae and genus Lanx (Baker 1925; Pilsbry 1925; Turgeon et al. 1998). This species has also previously been described as a member of the subgenus Walkerola (Hannibal 1912; Burch 1989). Others (Taylor 1981; Frest and Johannes 1995) do not recognize the subgenus, and also indicate that shell height to width ratio should be considered a species- not genus-level character. The scale lanx is an aquatic pulmonate snail in the family Lymnaeidae. It has a complete circumferential muscle scar, easily distinguishing species in this family from other freshwater limpets (Burch 1989). This species has a large shell (11-16mm length, 7.5-9.5mm width, and 3-3.5mm height, Hannibal 1912; Henderson 1936). It is recognizable by its characteristic flattened, thin shell whose width and length is many times greater than height (Hannibal 1912; Pilsbry 1925; Henderson 1936; Frest and Johannes 1995). Life History: The scale lanx is a freshwater snail lacking gills, ctenidia, and lung-like structures, breathing instead through a vascularized mantle (Pilsbry 1925; Frest and Johannes 2005). Although the specific mode of breeding and reproduction is unstudied in this species, basommatophoran snails generally reproduce sexually, and lymnaeids in particular are hermaphroditic. -

Sensitivity of Freshwater Snails to Aquatic Contaminants: Survival and Growth of Endangered Snail Species and Surrogates in 28-D

Sensitivity of freshwater snails to aquatic contaminants: Survival and growth of endangered snail species and surrogates in 28-day exposures to copper, ammonia and pentachlorophenol John M. Besser, Douglas L. Hardesty, I. Eugene Greer, and Christopher G. Ingersoll U.S. Geological Survey, Columbia Environmental Research Center, Columbia, Missouri Administrative Report (CERC-8335-FY07-20-10) submitted to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) Project Number: 05-TOX-04, Basis 8335C2F, Task 3. Project Officer: Dr. David R. Mount USEPA/ORD/NHEERL Mid-Continent Ecology Division 6201 Congdon Blvd, Duluth, MN 55804 USA April 13, 2009 Abstract – Water quality degradation may be an important factor affecting declining populations of freshwater snails, many of which are listed as endangered or threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Toxicity data for snails used to develop U.S. national recommended water quality criteria include mainly results of acute tests with pulmonate (air-breathing) snails, rather than the non-pulmonate snail taxa that are more frequently endangered. Pulmonate pond snails (Lymnaea stagnalis) were obtained from established laboratory cultures and four taxa of non-pulmonate taxa from field collections. Field-collected snails included two endangered species from the Snake River valley of Idaho -- Idaho springsnail (Pyrgulopsis idahoensis; which has since been de-listed) and Bliss Rapids snail (Taylorconcha serpenticola) -- and two non-listed taxa, a pebblesnail (Fluminicola sp.) collected from the Snake River and Ozark springsnail (Fontigens aldrichi) from southern Missouri. Cultures were maintained using simple static-renewal systems, with adults removed periodically from aquaria to allow isolation of neonates for long-term toxicity testing. -

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016 April 1981 Revised, May 1982 2nd revision, April 1983 3rd revision, December 1999 4th revision, May 2011 Prepared for U.S. Department of Commerce Ohio Department of Natural Resources National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Division of Wildlife Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management 2045 Morse Road, Bldg. G Estuarine Reserves Division Columbus, Ohio 1305 East West Highway 43229-6693 Silver Spring, MD 20910 This management plan has been developed in accordance with NOAA regulations, including all provisions for public involvement. It is consistent with the congressional intent of Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, and the provisions of the Ohio Coastal Management Program. OWC NERR Management Plan, 2011 - 2016 Acknowledgements This management plan was prepared by the staff and Advisory Council of the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve (OWC NERR), in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources-Division of Wildlife. Participants in the planning process included: Manager, Frank Lopez; Research Coordinator, Dr. David Klarer; Coastal Training Program Coordinator, Heather Elmer; Education Coordinator, Ann Keefe; Education Specialist Phoebe Van Zoest; and Office Assistant, Gloria Pasterak. Other Reserve staff including Dick Boyer and Marje Bernhardt contributed their expertise to numerous planning meetings. The Reserve is grateful for the input and recommendations provided by members of the Old Woman Creek NERR Advisory Council. The Reserve is appreciative of the review, guidance, and council of Division of Wildlife Executive Administrator Dave Scott and the mapping expertise of Keith Lott and the late Steve Barry. -

12-Month Finding on a Petition to Remove the Bliss Rapids Snail

47536 Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 178 / Wednesday, September 16, 2009 / Proposed Rules (2) The amount of the allotment for (1) The State has submitted to the claimed during a 2-year period of each of the 50 States and the District of Secretary, and has approved by the availability, beginning with the fiscal Columbia, and for each of the Secretary a State plan amendment or year of the final allotment and ending Commonwealths and Territories (not waiver request relating to an expansion with the end of the succeeding fiscal including the additional amount for FY of eligibility for children or benefits year following the fiscal year. 2009 determined under paragraph under title XXI of the Act that becomes Authority: (Section 1102 of the Social (c)(2)(ii) of this section) is equal to the effective for a fiscal year (beginning Security Act (42 U.S.C. 1302) product of: with FY 2010 and ending with FY (Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance (i) The percentage determined by 2013); and Program No. 93.778, Medical Assistance dividing the amount in paragraph (2) The State has submitted to the Program) (e)(2)(i)(A) by the amount in paragraph Secretary, before the August 31 (Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance (e)(2)(i)(B) of this section. preceding the beginning of the fiscal Program No. 93.767, State Children’s Health (A) The amount of the State allotment year, a request for an expansion Insurance Program)) allotment adjustment under this for each of the 50 States and the District Dated: June 19, 2009. -

Native Unionoida Surveys, Distribution, and Metapopulation Dynamics in the Jordan River-Utah Lake Drainage, UT

Version 1.5 Native Unionoida Surveys, Distribution, and Metapopulation Dynamics in the Jordan River-Utah Lake Drainage, UT Report To: Wasatch Front Water Quality Council Salt Lake City, UT By: David C. Richards, Ph.D. OreoHelix Consulting Vineyard, UT 84058 email: [email protected] phone: 406.580.7816 May 26, 2017 Native Unionoida Surveys and Metapopulation Dynamics Jordan River-Utah Lake Drainage 1 One of the few remaining live adult Anodonta found lying on the surface of what was mostly comprised of thousands of invasive Asian clams, Corbicula, in Currant Creek, a former tributary to Utah Lake, August 2016. Summary North America supports the richest diversity of freshwater mollusks on the planet. Although the western USA is relatively mollusk depauperate, the one exception is the historically rich molluskan fauna of the Bonneville Basin area, including waters that enter terminal Great Salt Lake and in particular those waters in the Jordan River-Utah Lake drainage. These mollusk taxa serve vital ecosystem functions and are truly a Utah natural heritage. Unfortunately, freshwater mollusks are also the most imperiled animal groups in the world, including those found in UT. The distribution, status, and ecologies of Utah’s freshwater mussels are poorly known, despite this unique and irreplaceable natural heritage and their protection under the Clean Water Act. Very few mussel specific surveys have been conducted in UT which requires specialized training, survey methods, and identification. We conducted the most extensive and intensive survey of native mussels in the Jordan River-Utah Lake drainage to date from 2014 to 2016 using a combination of reconnaissance and qualitative mussel survey methods. -

Aquatic Snails of the Snake and Green River Basins of Wyoming

Aquatic snails of the Snake and Green River Basins of Wyoming Lusha Tronstad Invertebrate Zoologist Wyoming Natural Diversity Database University of Wyoming 307-766-3115 [email protected] Mark Andersen Information Systems and Services Coordinator Wyoming Natural Diversity Database University of Wyoming 307-766-3036 [email protected] Suggested citation: Tronstad, L.M. and M. D. Andersen. 2018. Aquatic snails of the Snake and Green River Basins of Wyoming. Report prepared by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database for the Wyoming Fish and Wildlife Department. 1 Abstract Freshwater snails are a diverse group of mollusks that live in a variety of aquatic ecosystems. Many snail species are of conservation concern around the globe. About 37-39 species of aquatic snails likely live in Wyoming. The current study surveyed the Snake and Green River basins in Wyoming and identified 22 species and possibly discovered a new operculate snail. We surveyed streams, wetlands, lakes and springs throughout the basins at randomly selected locations. We measured habitat characteristics and basic water quality at each site. Snails were usually most abundant in ecosystems with higher standing stocks of algae, on solid substrate (e.g., wood or aquatic vegetation) and in habitats with slower water velocity (e.g., backwater and margins of streams). We created an aquatic snail key for identifying species in Wyoming. The key is a work in progress that will be continually updated to reflect changes in taxonomy and new knowledge. We hope the snail key will be used throughout the state to unify snail identification and create better data on Wyoming snails. -

Pacific Northwest Region Invasive Plant Program Preventing and Managing Invasive Plants Final Environmental Impact Statement

Pacific Northwest Region Invasive Plant Program Preventing and Managing Invasive Plants Final Environmental Impact Statement USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Region States of Oregon and Washington, Including Portions of Del Norte and Siskiyou Counties in California, and Portions of Nez Perce, Salmon, Idaho, and Adams Counties in Idaho Lead Agency: USDA Forest Service Responsible Official: Linda Goodman, Regional Forester Pacific Northwest Region 333 SW First Ave. PO Box 3623 Portland, OR 97208 For More Information: IPEIS, Eugene Skrine, Team Leader PO Box 3623 Portland, OR 97208 Ph: (503) 808-2685 Fax: (503) 808-2699 Email: [email protected] www.fs.fed.us/r6/invasiveplant-eis Abstract: The Forest Service proposes to add management direction to all existing National Forest Land and Resource Management Plans in the Pacific Northwest Region (Region Six). This direction would standardize invasive plant prevention, and expand the set of invasive plant treatment tools available for use on National Forests in Region Six. The FEIS considers four alternatives in detail (including No Action). Adoption of the standards in any of the action alternatives would likely reduce the extent and rate of spread of invasive plants across the region, and help prevent new infestations. All of the action alternatives include standards to protect human health and the environment. The Forest Service preferred alternative is the Proposed Action. Preventing and Managing Invasive Plants Final Environmental Impact Statement April 2005 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. -

Invertebrates

State Wildlife Action Plan Update Appendix A-5 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Fact Sheets INVERTEBRATES Conservation Status and Concern Biology and Life History Distribution and Abundance Habitat Needs Stressors Conservation Actions Needed Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 2015 Appendix A-5 SGCN Invertebrates – Fact Sheets Table of Contents What is Included in Appendix A-5 1 MILLIPEDE 2 LESCHI’S MILLIPEDE (Leschius mcallisteri)........................................................................................................... 2 MAYFLIES 4 MAYFLIES (Ephemeroptera) ................................................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Cinygmula gartrelli) .................................................................................................................... 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia falcula) ............................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia jenseni) ............................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Siphlonurus autumnalis) .............................................................................................................. 4 [unnamed] (Cinygmula gartrelli) .................................................................................................................... 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia falcula) ........................................................................................................... -

Rare, Threatened and Endangered Invertebrate Species of Oregon

Rare, Threatened and Endangered Invertebrate Species of Oregon August 2016 Oregon Biodiversity Information Center, Portland, Oregon Scientific Name Ecoregion; Adjacent States Heritage Federal ODFW ORBIC Common Name Oregon Counties Rank Status Status List INVERTEBRATES Class Turbellaria - Flatworms Order Tricladida Kenkia rhynchida BR G1G2 SOC-- 1 A flatworm (planarian) Harn S1S2 CS Class Bivalvia - Clams, Oysters and Mussels Order Ostreoida Ostrea conchaphila CR, ME; WA G5 -- -- 3 Native oyster Linc, Till SNR Order Unionoida Anodonta californiensis BM, BR, CB, CR, EC, WC, WV; CA, ID, NV, WA + G3Q SOC-- 3 California floater (mussel) Clat, Colu, Coos?, Desc, Gran, Harn, Klam, Linn, Malh, S2 CS Mult, Sher, Wasc, Wash Anodonta nuttalliana BM, BR, CB, CR, EC?, KM, WC, WV; BC, CA, ID, NV, G4Q -- -- 3 Winged floater (mussel) WA + S1? CS Bake, Clac, Clat, Colu, Coos, Desc, Doug, Gran, Harn, Jack, Jeff, Jose, Klam, Lake, Lane, Linc, Linn, Malh, Morr, Mult, Umat, Wasc?, Wash, Whee Anodonta oregonensis BM, BR, CB, CR, EC, KM, WC, WV; AK, BC, CA, ID, G5Q -- -- 2 Oregon floater (mussel) NV, UT, WA S3? Bake, Bent, Clac, Clat, Colu, Coos, Doug, Gran, Harn, Hood, Jack, Klam, Lake, Lane, Linc, Linn, Mari, Mult, Polk, Sher, Umat, Wasc, Wash, Yamh Gonidea angulata BM, BR, CB, CR, EC, KM, WC, WV; BC, CA, ID, NV, G3 -- -- 2 Western ridged mussel WA + S2S3 CS Bake, Bent, Clac, Colu, Coos, Croo, Curr, Desc, Doug, Gran, Harn, Jeff, Jose, Klam, Linn, Malh, Mari, Morr, Mult, Umat, Unio, Wall, Wasc, Wash, Whee, Yamh Margaritifera falcata BM, BR, CB, CR, EC, KM, WC, WV; AK, BC, CA, ID, G5 -- -- 2 Western pearlshell (mussel) NV, WA + S3 Bake, Bent, Clac, Clat, Colu, Coos, Croo, Curr, Desc, Doug, Gran, Harn, Hood, Jack, Jeff, Jose, Klam, Lake, Lane, Linc, Linn, Malh, Mari, Morr, Mult, Polk, Sher, Till, Umat, Unio, Wall, Wasc, Wash, Whee, Yamh Order Veneroida Pisidium sp.