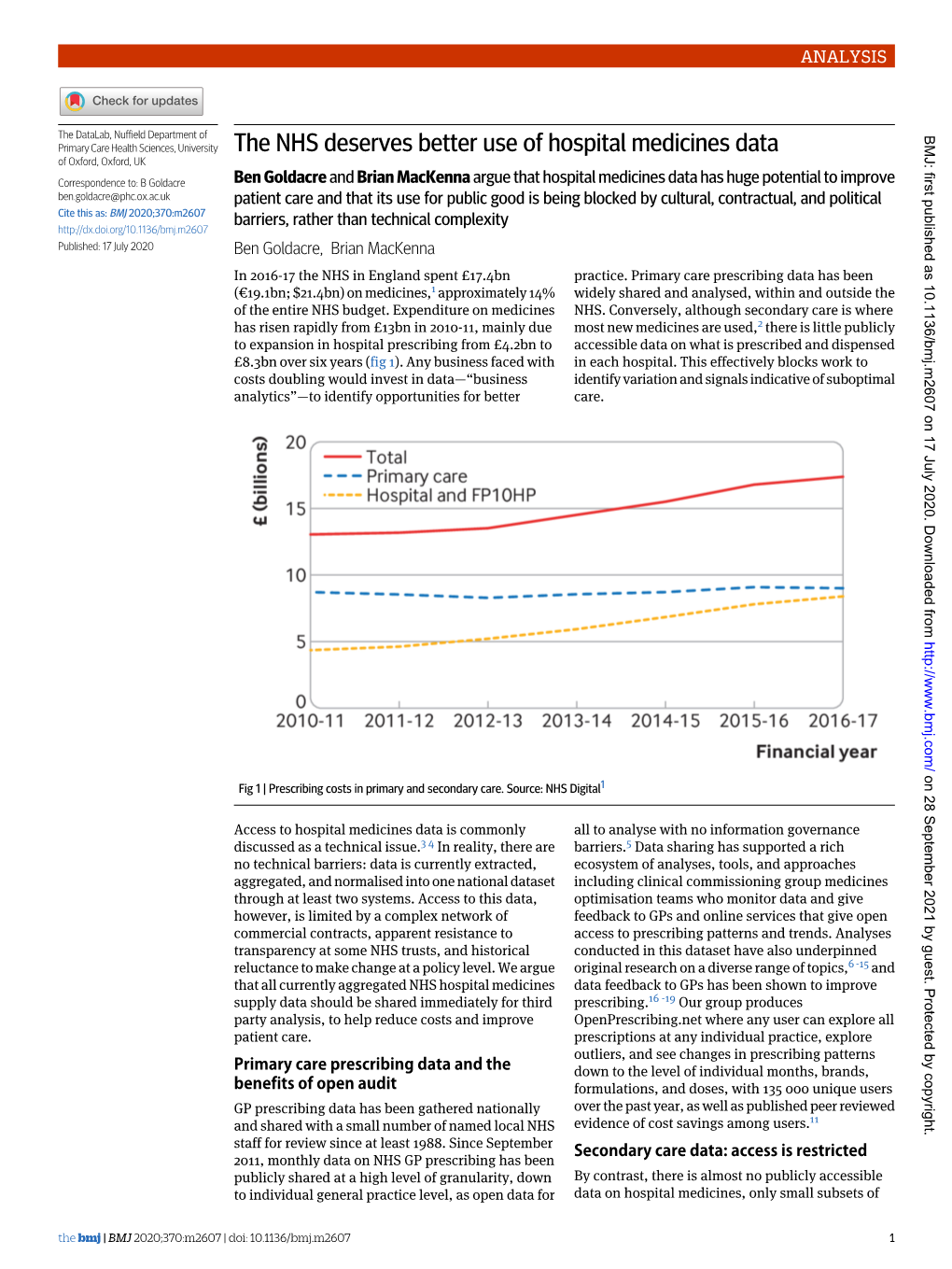

The NHS Deserves Better Use of Hospital Medicines Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Response from NHS Digital

1 Trevelyan Square Boar Lane Leeds LS1 6AE FAO: Joanne Andrews North East Kent Coroners Cantium House Country Hall Sandling Road Maidstone Kent ME14 1XD By Email Only: [email protected] Your ref: Our ref: 4 February 2021 Dear Ms Andrews Inquest into the death of Mr Ronald Richard Tilley I am writing in response to the Regulation 28 report received from HM Coroner dated 4 December 2020. This follows the death of Ronald Richard Tilley, who sadly died on 23 October 2019. This was followed by an investigation and inquest which concluded on 29 October 2020. I would like to express my sincerest condolences to Mr Tilley’s family. NHS Digital provided written statements in advance of the inquest, but did not attend the inquest. NHS Digital is a non-departmental public body created by the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and is the national information and technology partner for the health and care system. We use technology to support the NHS and social care. NHS Digital operates and maintains the Personal Demographics Service (‘PDS’) under the Spine Services No.2 Directions issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care to maintain a register of NHS patients in England. PDS is the national electronic database of NHS patient details such as name, address, date of birth and NHS Number (known as demographic data). It also records the primary care registration (i.e. the GP practice with which the patient is registered for general medical services1) held by each registered patient and as notified through other NHS systems. -

Health Research Authority Board Meeting Agenda Part 1 – Public Session

Page 1 of 63 HEALTH RESEARCH AUTHORITY BOARD MEETING AGENDA PART 1 – PUBLIC SESSION Date: Tuesday 24 July 2018 Time: 1.30pm – 3.15pm Venue: etc venues, Avonmouth House, 6 Avonmouth Street, London SE1 6NX Item Item details Time Attachment Page (mins) no 1. Apologies Verbal - Janet Messer Janet Wisely 2. Conflicts of interest Verbal - 3. Minutes of the last meeting 10 - 16 May 2018 A 4. Matters arising Verbal - Including: - HRA Annual Report and Accounts 2017-18 published 5. Update from Chair 5 Verbal - 6. Chief Executive update 10 To be tabled - 7. HRA Directorate update 5 To be tabled - 8. Transformation Programme update 10 B Including: - SIP Proportionality project 10 C 9. Update on progress of research transparency work 5 Verbal - 10. Pilot proposal for an HRA Accountable Centre Model for 15 D improvement evaluations Page 1 of 2 HRA Board Meeting Agenda – Part 1 (2018.07.24) Page 2 of 63 11. Finance report: April – June 2018 10 E Items for information 12. Annual Freedom of Information Report (2017/18) F 13. Annual Complaints Report (2017/18) G 14. Summary of 06.06.2018 Audit & Risk Committee meeting H 15. Out of session business conducted / External areas of Verbal interest since previous meeting 10 - Update regarding recruitment of Nick Hirst to support Research System Programme circulated 07 June 2018 - Statement issued by NIHR regarding Improving Performance in Initiating and Delivering Clinical Research circulated 07 June 2018 - Update regarding two studies to be published circulated 17 June 2018 16. Any other business 5 Verbal - (Any AOB items should be notified to the Head of Corporate Governance no later than 24 hours prior to the Board meeting barring exceptional circumstances) 17. -

NHSX Job Description and Person Specification

NHSX Job description and person specification Position Job title Digital Delivery Adviser Directorate/ Region NHSX Pay band AFC Band 8d Responsible to Director of Screening Transformation Salary Accountable to Director of Screening Transformation From £75,914 - £ 87,754 per annum Tenure Permanent Responsible for Responsible for day to day work assigned to the Digital Transformation of Screening Programme Funding Admin funded Base London/Leeds with travel between both locations Arrangements NHSX NHS England and NHS Improvement NHSX is leading the largest digital health and social care transformation NHSX is a joint until between DHSC and NHSE/I. This role is being recruited programme in the world and has been created to give staff and citizens the into NHSE/I. technology they need. NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSE/I) came together on 1 April 2019 We are a joint unit made up of colleagues in the Department of Health and as a new single organisation. The NHS Long Term Plan focuses on delivering Social Care (DHSC) and NHS England and Improvement (NHSE/I) and integrated care to patients at the local level and we can best support the NHS will harness the best expertise from industry, the NHS, Government and to deliver this as a single integrated organisation. the health and care sectors. Our new operating model represents a strong shift to regional delivery NHSX will deliver the Health Secretary’s Tech Vision, building on the NHS supported by expert corporate teams. Local health systems are supported by Long Term Plan. We will speed up the digital transformation of the NHS and our integrated regional teams who play a major leadership role in the social care. -

A Buyer's Guide to AI in Health and Care

A Buyer’s Guide to AI in Health and Care 10 questions for making well-informed procurement decisions about products that use AI TRANSPARENCY CONFIDENTIALITY NOVEMBER 2020 PRIVACY AUTONOMY 4 1 ACCELERATINGTHE SAFEANDEFFECTIVE ADOPTIONOFAI INHEALTHANDCARE NHSX A Buyer’s Guide to AI in Health and Care 2 3 CONTENTS Foreword4 Procurementanddelivery64 Executivesummary6 Isyourprocurementprocessfair,transparentandcompetitive?64 Introduction18 Can you ensure a commercially and legally robust contractual outcome for your organisation,andthehealthandcaresector?66 Problemidentification22 Acknowledgements70 What problem are you trying to solve, and is artificial intelligence the right solution?22 Furtherinformation72 Productassessment24 Doesthisproductmeetregulatorystandards?24 Doesthisproductperforminlinewiththemanufacturer’sclaims?33 Implementationconsiderations48 Willthisproductworkinpractice?48 Canyousecurethesupportyouneedfromstaffandserviceusers?52 Can you build and maintain a culture of ethical responsibility around this project?54 What data protection protocols do you need to safeguard privacy and comply withthelaw?56 Canyoumanageandmaintainthisproductafteryouadoptit?60 AUTHORS Dr. Indra Joshi and Dominic Cushnan 4 5 Foreword Artificial intelligence (AI) is already impacting positively on our health and care This is where the Buyer’s Guide to AI in Health and Care comes in. It is aimed at system - for example, supporting diagnostic decisions, predicting care needs, anyone likely to be involved in weighing up the pros and cons of buying a informing resource planning, and generating game-changing research. We need product that uses AI. It is recommended reading for clinical and practitioner to harness its promise to reap tangible benefits for patients, service users and leads, chief officers, senior managers, transformation experts and procurement staff. That’s why the Government announced a £250m investment last year to leads. It offers practical guidance on the questions to be asking before and set up an Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (AI Lab). -

Health Education England Annual Report and Accounts 2020-21

Annual Report and Accounts 2020-21 Health Education England (Executive Non-Departmental Public Body) www.hee.nhs.uk We work with partners to plan, recruit, educate and train the health workforce. HC 266 Health Education England (Executive Non-Departmental Public Body) Annual Report and Accounts 2020-21 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Paragraph 26 (4) of Schedule 5 of the Care Act 2014 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 15 July 2021 HC 266 © Crown copyright 2021 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us via www.hee.nhs.uk ISBN 978-1-5286-2444-2 CCS0221001382 06/21 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office About Health Education England Health Education England exists for one reason only: our vision is to help improve the quality of life and health and care services for the people of England by ensuring the workforce of today and tomorrow has the right skills, values and behaviours, in the right numbers, at the right time and in the right place. Our purpose as part of the NHS, is We serve … to work with partners to plan, recruit, educate and train the health workforce. -

The Impact of Covid-19 on the Use of Digital Technology in the NHS

Briefing August 2020 The impact of Covid-19 on the use of digital technology in the NHS Rachel Hutchings Key points • The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in the rapid adoption of digital technology in the NHS and significant changes in the delivery of services more widely – to free up space and capacity in acute hospitals, enable remote working and reduce the risk of infection transmission in NHS settings. Primary care in particular has seen a huge increase in remote appointments. • There has also been a surge in patients’ uptake of remote health services, including registrations for the NHS App, NHS login and e-prescription services. • These changes have happened at an incredible pace. Central bodies have taken steps to enable the changes to occur, providing guidance on information governance and fast-track procurement frameworks, for example. Meanwhile, health care professionals have had to respond innovatively to continue to provide services to patients. • But despite the undeniable progress that has been made, it is important to proceed with caution. Especially when changes happen at such a pace, there are possible risks and downsides. • It is essential that we understand – through robust evaluation and research – what the impact of the rapid shift towards digital technology has been on clinical practice, patients’ access to and quality of care, and the experiences of patients and staff. Studies in these areas remain limited, so more work is needed to learn from the experience and determine whether we need to revisit existing priorities. • To embed the positive work that has been done during the pandemic and ensure that it is sustainable in the future, it needs to be underpinned by adequate funding, infrastructure and the necessary workforce. -

Consent and Participation Information Sheet Guidance

Skip the navigation and go straight to content. Consent and Participant Information Guidance Home Principles Style Content Examples & Templates What's New Resources Home > Home Welcome to the Health Research Authority's online guidance for researchers and ethics committees on consent, and how to prepare materials to support this process. In this guidance you will find information on: The principles of consent (both ethical and legal) How the principles relate to preparation and use of a Participant Information Sheet (PIS) and consent form Recommended content of a PIS and consent form Design and style of an effective PIS and consent form The guidance covers consent in adults, children, young people and adults not able to consent for themselves (in both emergency and non-emergency situations) and takes into account UK- wide requirements. NOTE: wherever we use the terms ‘Participant Information Sheet’, ‘PIS’ and/or ‘consent form’ we are including where these materials are provided in electronic formats. We have provided some examples and suggested text. The guidance should be considered as a framework, not a rigid template: we would encourage you to think carefully about how best to inform potential participants. One size does not fit all: you do not need to produce the same PIS and consent form to support consent for a questionnaire study as you would to recruit into a drug trial. The best way to make sure your consent documentation is fit for purpose is to test it with patient groups or other members of the public. From this site we have provided links to other sources of information (available from our 'Resources' page). -

A Digital NHS? an Introduction to the Digital Agenda and Plans for Implementation

BRIEFING A digital NHS? An introduction to the digital agenda and plans for implementation Authors Matthew Honeyman Phoebe Dunn Helen McKenna September 2016 A digital NHS? Key messages • Digital technology has the potential to transform the way patients engage with services, improve the efficiency and co-ordination of care, and support people to manage their health and wellbeing. • Previous efforts to digitise health care have resulted in considerable progress being made in primary care, while secondary care lags significantly behind. • The government and national NHS leaders have set out a high-level vision and goals for digitising the NHS. However, there is a risk that expectations have been set too high and there has been a lack of clarity about the funding available to support this work. • In view of this, we welcome the more realistic deadlines called for in the Wachter review. We also welcome the Wachter review’s conclusion that current funding would be insufficient to achieve the goals set for 2020. • This agenda has been subject to a confusing array of announcements, initiatives and plans. Shifting priorities and slipping timescales pose a risk to credibility and commitment on the ground. • Ministers and national leaders must now set out a definitive plan which clarifies priorities and sets credible timescales, generates commitment and momentum, and is achievable given the huge financial and operational pressures facing the NHS. This requires urgent clarification about when funding already announced will be available and how this can be accessed. Holding back investment until the end of the parliament, as appears to be planned, will impact on the ability of local areas to make significant progress. -

Achieving a Digital NHS Lessons for National Policy from the Acute Sector

Research report May 2019 Achieving a digital NHS Lessons for national policy from the acute sector Sophie Castle-Clarke and Rachel Hutchings Acknowledgements We are grateful to everyone at the trusts we visited who participated in our interviews and focus groups and supported the organisation of our visits. We are also grateful to all of the individuals who participated in the scoping conversations and the policy workshop. Special thanks to the reviewers who provided comments on an earlier draft including Helen Buckingham (Director of Strategy and Operations, Nuffield Trust), Nigel Edwards (Chief Executive Officer, Nuffield Trust), Harry Evans (Researcher, The King’s Fund), John Farenden (Senior Programme Lead, Local Health and Care Record Programme, NHS England), Iain Fletcher (Senior Programme Lead for Blueprinting, Global Digital Exemplar Programme, NHS England), Lorraine Foley (Chief Executive, Professional Record Standards Body), James Freed (Chief Information Officer, Health Education England), Dr Charles Gutteridge (Chief Clinical Information Officer, Barts Health NHS Trust), Dr Sarah Scobie (Deputy Director of Research) and Ann Slee (Associate Chief Clinical Information Officer (Medicines) and e-prescribing lead, NHS England). With particular thanks to Rob Parker (Associate Chief Information Officer, NHS England) for his continued support and assistance with the project. Finally, we are grateful for the small contribution NHS England made to the funding of this project. Find out more online at: www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research Contents Foreword 2 Summary 3 Introduction 9 1 The role of national policy in achieving a digital health system 13 2 Configuring a digital workforce 31 3 Working with digital suppliers 49 4 Making use of data across the system 56 5 Funding and sustainability 65 6 Reflecting on the Global Digital Exemplar and Fast Follower programme 74 7 Concluding thoughts 86 Glossary 89 References 94 Achieving a digital NHS 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Foreword Digitising the NHS has been an important goal of national policy for many years. -

NHS Digital Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20 Our Experiences Over the Past the Fight Continues

2019-20 Annual Report and Accounts Information and technology for better health and care Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20 The Health and Social Care Information Centre is an executive non-departmental public body created by statute, also known as NHS Digital. Presented to Parliament pursuant to Schedule 18, paragraph 12(2)(a) of the Health and Social Care Act 2012. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 16 July 2020. HC 537 © NHS Digital copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/ open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third-party copyright information, you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-5286-2041-3 CCS0520637790 07/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Contact us: NHS Digital 1 Trevelyan Square Boar Lane Leeds LS1 6AE Telephone: 0300 303 5678 [email protected] www.digital.nhs.uk Contents Chairman’s foreword 6 Performance report 8 Chief Executive’s introduction 8 What we did in 2019-20 10 Performance analysis 34 Accountability report 40 Corporate governance report 41 Remuneration and staff report 48 Salaries and pensions of senior management 58 Annual governance statement 64 Statement of Accounting Officer’s responsibilities 72 Parliamentary accountability and audit report 73 The certificate and report of the Comptroller and Auditor General to the Houses of Parliament 74 2019-20 Accounts 77 Notes to the accounts 82 Board members’ biographies and register of interests 108 5 Chairman’s foreword Over the past few months, we have faced the most serious public health emergency in a century. -

NHS Digital and MRC Researcher Roadshow

NHS Digital and MRC Researcher Roadshow Presented by Estelle Spence, Strategic Engagement Manager, Research & Life Sciences Today’s Roadshow • Welcome • Agenda & key timings • Our approach – 4 keys: – Working together – Open & transparent – Interaction to build understanding – Continually improve based on your feedback Working together & improving communications • Research Advisory Group (RAG) • Membership & purpose • Find out more: http://www.digital.nhs.uk/research-advisory-group Research Bulletin Current & upcoming datasets Data Access Request Service (DARS) Presented by Garry Coleman, Head of Data Access NHS Digital data products available via DARS • Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) • Primary Care Mortality Data (PCMD) • Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) • Secondary Uses Services Payments by Results (SUS PbR) • Mental Health Data Sets (MHMDS, MHLDDS) • Diagnostic Imaging Datasets (DIDS) • Personal Demographics Services (PDS) Registration • Public Health England (PHE) Cancer – for cohorts • Office for National Statistics (ONS) Mortality (Civil Registration data) • Linked local flows through DSCROs …plus others to come…and linked data products Health Data Interrogation Service (HDIS) What? Why? How? Who? • HDIS is an online • SAS Enterprise • Users have secure • Access to HDIS is service that allows Guide is a access through a only provided to registered users to powerful Microsoft web browser or UK organisations securely access Windows client through VMware where there is a datasets; one can application. software. sufficient purpose interrogate the • There are no • SAS Enterprise justifying access data, perform substantive data Guide provided for with clear benefits aggregations, storage analysis. to health and statistical analysis, requirements to • We are looking to social care. & produce a range run the tool. expand the range of different of tools & data outputs. -

Post-COVID Landscape

The post-COVID landscape COVID-19 has changed the NHS in fundamental ways; from the levels of PTSD in our nurses and doctors, to the configuration of health systems, to the expectations of health information systems from staff and patients alike. There are a number of new information systems, several new bodies, as well as some new(ish) ‘partnerships’ and contractors. Quite a number of these have been assembled in haste in a crisis under emergency powers – not necessarily the ideal conditions under which to redesign a national health and care system. (If indeed any real ‘design’ effort is being put into social care...) The data controllers Under the COPI Notices, the Secretary of State (DHSC) has taken extraordinary powers, and given some to NHS England. Service control, hence data controllership, of NHS patients’ data – as well as local authority and variously-contracted social care service users’ data – is by its very nature widely distributed. Data controllers being a person or body which, “alone or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data” – i.e. a matter of fact, not of (contractual) assignment or assertion. In several instances during the pandemic, however, data controllership has become unhelpfully muddied. If we take a look at some of the high level constituent parts covered in ‘The data flows of COVID-19’ – only some of which most of the general public will be aware – then where does the data end up, and who is in control? ● Test and Trace, including the NHSx exposure notification app – DHSC is data controller; NHSx is neither a statutory nor formally constituted public body.