Landscape Architect Launcelot 'Capability' Brown and His Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Place Has Capabilities a Lancelot 'Capability' Brown Teachers Pack

This Place has Capabilities A Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown Teachers Pack Welcome to our teachers’ pack for the 2016 tercentenary of the birth of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown. Lancelot Brown was born in the small village of Kirkhale in Northumberland in 1716. His name is linked with more than 250 estates, throughout England and Wales, including Stowe in Buckinghamshire, Blenheim Palace (Oxfordshire) Dinefwr Park (Carmarthenshire) and, of course Chatsworth. His first visit to Chatsworth was thought to have been in 1758 and he worked on the landscape here for over 10 years, generally visiting about twice a year to discuss plans and peg out markers so that others could get on with creating his vision. It is thought that Lancelot Brown’s nickname came from his ability to assess a site for his clients, ‘this place has its capabilities’. He was famous for taking away traditional formal gardens and avenues to create ‘natural’ landscapes and believed that if people thought his landscapes were beautiful and natural then he had succeeded. 1 Education at Chatsworth A journey of discovery chatsworth.org Index Page Chatsworth Before Brown 3 Brown’s Chatsworth 6 Work in the Park 7 Eye-catchers 8 Work in the Garden and near the House 12 Back at School 14 Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown 2 Education at Chatsworth A journey of discovery chatsworth.org Chatsworth before Brown The Chatsworth that Brown encountered looked something like this: Engraving of Chatsworth by Kip and Knyff published in Britannia Illustrata 1707 The gardens were very formal and organised, both to the front and back of the house. -

The American Lawn: Culture, Nature, Design and Sustainability

THE AMERICAN LAWN: CULTURE, NATURE, DESIGN AND SUSTAINABILITY _______________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University _______________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Landscape Architecture _______________________________________________________________________________ by Maria Decker Ghys May 2013 _______________________________________________________________________________ Accepted by: Dr. Matthew Powers, Committee Chair Dr. Ellen A. Vincent, Committee Co-Chair Professor Dan Ford Professor David Pearson ABSTRACT This was an exploratory study examining the processes and underlying concepts of design nature, and culture necessary to discussing sustainable design solutions for the American lawn. A review of the literature identifies historical perceptions of the lawn and contemporary research that links lawns to sustainability. Research data was collected by conducting personal interviews with green industry professionals and administering a survey instrument to administrators and residents of planned urban development communi- ties. Recommended guidelines for the sustainable American lawn are identified and include native plant usage to increase habitat and biodiversity, permeable paving and ground cover as an alternative to lawn and hierarchical maintenance zones depending on levels of importance or use. These design recommendations form a foundation -

World War One: the Deaths of Those Associated with Battle and District

WORLD WAR ONE: THE DEATHS OF THOSE ASSOCIATED WITH BATTLE AND DISTRICT This article cannot be more than a simple series of statements, and sometimes speculations, about each member of the forces listed. The Society would very much appreciate having more information, including photographs, particularly from their families. CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 The western front 3 1914 3 1915 8 1916 15 1917 38 1918 59 Post-Armistice 82 Gallipoli and Greece 83 Mesopotamia and the Middle East 85 India 88 Africa 88 At sea 89 In the air 94 Home or unknown theatre 95 Unknown as to identity and place 100 Sources and methodology 101 Appendix: numbers by month and theatre 102 Index 104 INTRODUCTION This article gives as much relevant information as can be found on each man (and one woman) who died in service in the First World War. To go into detail on the various campaigns that led to the deaths would extend an article into a history of the war, and this is avoided here. Here we attempt to identify and to locate the 407 people who died, who are known to have been associated in some way with Battle and its nearby parishes: Ashburnham, Bodiam, Brede, Brightling, Catsfield, Dallington, Ewhurst, Mountfield, Netherfield, Ninfield, Penhurst, Robertsbridge and Salehurst, Sedlescombe, Westfield and Whatlington. Those who died are listed by date of death within each theatre of war. Due note should be taken of the dates of death particularly in the last ten days of March 1918, where several are notional. Home dates may be based on registration data, which means that the year in 1 question may be earlier than that given. -

De Sussex Spaniel

Meesterwerk Tekst en illustraties: Ria Hörter Augustus Elliot Fuller (1777-1857) De Sussex Spaniel In Meesterwerk stellen we hondenrassen voor die zonder die ene fokker niet zouden bestaan. Dit keer is die fokker een steenrijke Engelse landeigenaar, woonachtig in Sussex, Wales en Londen en eigenaar van overzeese bezittingen. Zijn negentiende eeuwse ’Rose Hill’ Spaniels staan model voor de huidige Sussex Spaniels... Zwaar werk die rond 1795 aanwijsbaar begint met voorlopers. Het verhaal van de Sussex Vrijwel iedere kynologische auteur het fokken van Spaniels voor de jacht. Spaniel begint – hoe kan het anders – gaat er van uit dat Augustus Elliot (ook Spaniels die we vandaag de dag als in het Engelse graafschap Sussex, in gespeld Eliot, Eliott of Elliott) Fuller Sussex Spaniels betitelen of die we zuidoost Engeland. De Sussex Spaniel één van de eersten, zo niet de eerste, is tenminste kunnen zien als hun vroege werd en wordt gefokt voor de jacht in • De afbeelding met Spaniels uit Sydenham Edwards’ ’Cynographia Brittannica’ (1799-1805). Vier Spaniels in de kleuren lever en wit, zwart en wit, zandkleurig lever en lemon en wit. Getekend in de periode dat Augustus Fuller begint met de fokkerij van Sussex Spaniels. 64 Onze Hond 10 | 2010 Meesterwerk de dichte begroeiing op de zware kleigronden in dit graafschap. Niet zo maar een Spaniel, maar een zwaarge- bouwde hond voor zwaar werk. Squire De familie Fuller heeft haar wortels in Uckfield en Waldron (oost Sussex). De oudste Fuller die ik heb kunnen vinden is John Fuller, een rechtstreekse voorvader van Augustus Elliot, die in 1446 in Londen wordt geboren. -

27 September 2004

CLIVEDEN PRESS BACKGROUND INFORMATION INTRODUCTION Cliveden House is a five-star luxury hotel owned by the National Trust and operated under a long lease arrangement by the owners of Chewton Glen, who added the world-famous property to their portfolio on Thursday 2nd February 2012. Chewton Glen and Cliveden fall under the guidance and direction of Managing Director, Andrew Stembridge and both iconic hotels remain independently operated with a shared vision for unparalleled luxury, attention to detail and the finest levels of service. Cliveden is a grand stately home; it commands panoramic views over the beautiful Berkshire countryside and the River Thames. The house is surrounded by 376 acres of magnificent National Trust formal gardens and parkland. Guests have included every British monarch since George I as well as Charlie Chaplin, Winston Churchill, Harold Macmillan, President Roosevelt, George Bernard Shaw, John Profumo, the infamous Christine Keeler, and many other well-known names from the past and present. Less than 45 minutes west of London and 20 minutes from London Heathrow Airport, the hotel has 38 rooms, including 15 spacious suites, a summerhouse by the Thames, together with boathouse and boats, heated pool, spa and a range of sporting and leisure facilities. The André Garrett Restaurant is complemented by private dining, banqueting and meeting facilities. Both the original Cliveden, built in 1666 for the 2nd Duke of Buckingham and its replacement, built in 1824 were sadly destroyed by fire, the present Grade 1 listed Italianate mansion was built in 1851 by the architect Charles Barry for George Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, 2nd Duke of Sutherland. -

Roads in the Battle District: an Introduction and an Essay On

ROADS IN THE BATTLE DISTRICT: AN INTRODUCTION AND AN ESSAY ON TURNPIKES In historic times travel outside one’s own parish was difficult, and yet people did so, moving from place to place in search of work or after marriage. They did so on foot, on horseback or in vehicles drawn by horses, or by water. In some areas, such as almost all of the Battle district, water transport was unavailable. This remained the position until the coming of the railways, which were developed from about 1800, at first very cautiously and in very few districts and then, after proof that steam traction worked well, at an increasing pace. A railway reached the Battle area at the beginning of 1852. Steam and the horse ruled the road shortly before the First World War, when petrol vehicles began to appear; from then on the story was one of increasing road use. In so far as a road differed from a mere track, the first roads were built by the Roman occupiers after 55 AD. In the first place roads were needed for military purposes, to ensure that Roman dominance was unchallenged (as it sometimes was); commercial traffic naturally used them too. A road connected Beauport with Brede bridge and ran further north and east from there, and there may have been a road from Beauport to Pevensey by way of Boreham Street. A Roman road ran from Ore to Westfield and on to Sedlescombe, going north past Cripps Corner. There must have been more. BEFORE THE TURNPIKE It appears that little was done to improve roads for many centuries after the Romans left. -

Kentish Weald

LITTLE CHART PLUCKLEY BRENCHLEY 1639 1626 240 ACRES (ADDITIONS OF /763,1767 680 ACRES 8 /798 OMITTED) APPLEDORE 1628 556 ACRES FIELD PATTERNS IN THE KENTISH WEALD UI LC u nmappad HORSMONDEN. NORTH LAMBERHURST AND WEST GOUDHURST 1675 1175 ACRES SUTTON VALENCE 119 ACRES c1650 WEST PECKHAM &HADLOW 1621 c400 ACRES • F. II. 'educed from orivinals on va-i us scalP5( 7 k0. U 1I IP 3;17 1('r 2; U I2r/P 42*U T 1C/P I;U 27VP 1; 1 /7p T ) . mhe form-1 re re cc&— t'on of woodl and blockc ha c been sta dardised;the trees alotw the field marr'ns hie been exactly conieda-3 on the 7o-cc..onen mar ar mar1n'ts;(1) on Vh c. c'utton vPlence map is a divided fi cld cP11 (-1 in thP ace unt 'five pieces of 1Pnii. THE WALDEN LANDSCAPE IN THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTERS AND ITS ANTECELENTS Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London by John Louis Mnkk Gulley 1960 ABSTRACT This study attempts to describe the historical geography of a confined region, the Weald, before 1650 on the basis of factual research; it is also a methodological experiment, since the results are organised in a consistently retrospective sequence. After defining the region and surveying its regional geography at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the antecedents and origins of various elements in the landscape-woodlands, parks, settlement and field patterns, industry and towns - are sought by retrospective enquiry. At two stages in this sequence the regional geography at a particular period (the early fourteenth century, 1086) is , outlined, so that the interconnections between the different elements in the region should not be forgotten. -

Willis Papers INTRODUCTION Working

Willis Papers INTRODUCTION Working papers of the architect and architectural historian, Dr. Peter Willis (b. 1933). Approx. 9 metres (52 boxes). Accession details Presented by Dr. Willis in several instalments, 1994-2013. Additional material sent by Dr Willis: 8/1/2009: WIL/A6/8 5/1/2010: WIL/F/CA6/16; WIL/F/CA9/10, WIL/H/EN/7 2011: WIL/G/CL1/19; WIL/G/MA5/26-31;WIL/G/SE/15-27; WIL/G/WI1/3- 13; WIL/G/NA/1-2; WIL/G/SP2/1-2; WIL/G/MA6/1-5; WIL/G/CO2/55-96. 2103: WIL/G/NA; WIL/G/SE15-27 Biographical note Peter Willis was born in Yorkshire in 1933 and educated at the University of Durham (BArch 1956, MA 1995, PhD 2009) and at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where his thesis on “Charles Bridgeman: Royal Gardener” (PhD 1962) was supervised by Sir Nikolaus Pevsner. He spent a year at the University of Edinburgh, and then a year in California on a Fulbright Scholarship teaching in the Department of Art at UCLA and studying the Stowe Papers at the Huntington Library. From 1961-64 he practised as an architect in the Edinburgh office of Sir Robert Matthew, working on the development plan for Queen’s College, Dundee, the competition for St Paul’s Choir School in London, and other projects. In 1964-65 he held a Junior Fellowship in Landscape Architecture from Harvard University at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection in Washington, DC, returning to England to Newcastle University in 1965, where he was successively Lecturer in Architecture and Reader in the History of Architecture. -

'Capability' Brown

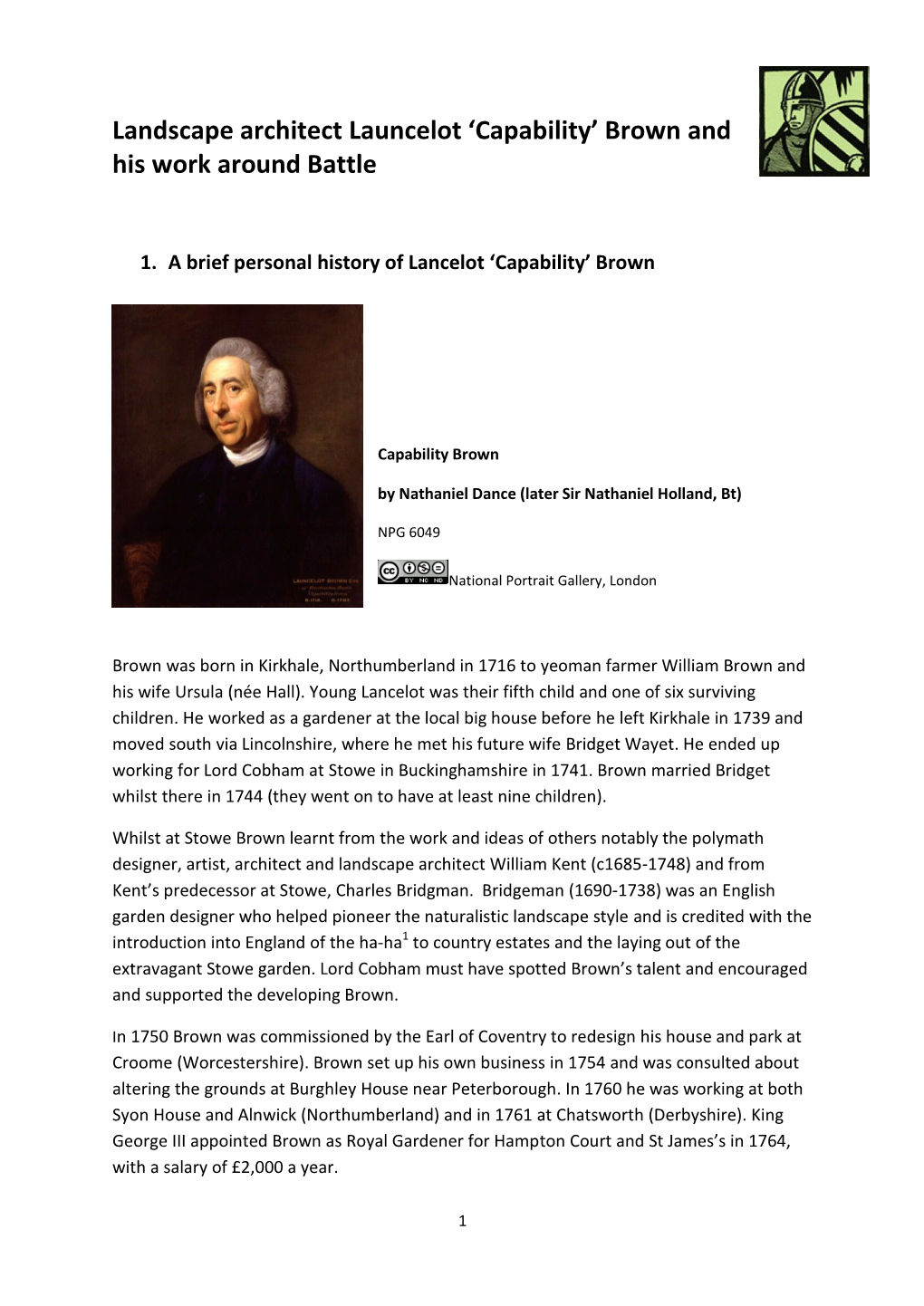

‘Capability’ Brown & The Landscapes of Middle England Introduction (Room ) Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown was born in in the Northumbrian hamlet of Kirkharle to a family of yeoman-farmers. The local landowner, Sir William Loraine, granted him his first gardening job at Kirkharle Hall in . Demonstrating his enduring capacity for attracting aristocratic patrons, by the time he was twenty-five Viscount Cobham had promoted him to the position of Head Gardener at Stowe. Brown then secured a number of lucrative commissions in the Midlands: Newnham Paddox, Great Packington, Charlecote Park (Room ) and Warwick Castle in Warwickshire, Croome Court in Worcestershire (Room ), Weston Park in Staffordshire (Room ) and Castle Ashby in Northamptonshire. The English landscape designer Humphry Repton later commented that this rapid success was attributable to a ‘natural quickness of perception and his habitual correctness of observation’. On November Brown married Bridget Wayet. They had a daughter and three sons: Bridget, Lancelot, William and John. And in Brown set himself up as architect and landscape consultant in Hammersmith, west of London, beginning a relentlessly demanding career that would span thirty years and encompass over estates. In , coinciding directly with his newly elevated position of Royal Gardener to George , Brown embarked on several illustrious commissions, including Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, and Luton Hoo in Bedfordshire. He then took on as business partner the successful builder-architect Henry Holland the Younger. Two years later, in , Holland married Brown’s daughter Bridget, thus cementing the relationship between the two families. John Keyse Sherwin, after Nathaniel Dance, Lancelot Brown (Prof Tim Mowl) As the fashion for landscapes designed in ‘the Park way’ increased in of under-gardeners. -

This Report Lists All Licences Issue Between 01/08/2021 and 31/08/2021. the Report Shows the Licence Number, the Most Recent Issue Date and the Address

This report lists all licences issue between 01/08/2021 and 31/08/2021. The report shows the licence number, the most recent issue date and the address. Where the licence is issued to somebody's home address, only the name is given. Alcohol and Entertainment Personal (Alcohol) LN/000014636 05/08/2021 Theiventhiran Maseethan LN/000014636 05/08/2021 Theiventhiran Maseethan LN/000025572 19/08/2021 Yung Ping Cowley LN/000017601 26/08/2021 Danny Mark Davis Premises (LA 2003) LN/000015241 16/08/2021 Winchelsea Sands Holiday Village, Pett Level Road, Winchelsea Beach, East Sussex, TN36 4NB LN/000016123 16/08/2021 The Broad Oak, Chitcombe Road, Broad Oak, East Sussex, TN31 6EU LN/000016117 18/08/2021 Tesco Express, 7-8 Collington Mansions, Collington Avenue, Bexhill, East Sussex, TN39 3PU LN/000015690 23/08/2021 Catsfield Post Office Stores, Post Office, The Green, Catsfield, East Sussex, TN33 9DJ LN/000015690 23/08/2021 Catsfield Post Office Stores, Post Office, The Green, Catsfield, East Sussex, TN33 9DJ Temporary Event Notice (Late) LN/000025496 02/08/2021 1 High Street, Battle, East Sussex, TN33 0AE LN/000025498 02/08/2021 Icklesham Recreation Ground, Main Road, Icklesham, East Sussex, TN36 4BS LN/000025499 02/08/2021 Blods Hall, Upper Sea Road, Bexhill, East Sussex, TN40 1RL LN/000025516 05/08/2021 Ashburnham Place, Ashburnham Place, Ashburnham, East Sussex, TN33 9NF LN/000025522 05/08/2021 Taris Coffee Bar, Workshop, Westfield Garage, Main Road, Westfield, East Sussex, TN35 4QE LN/000025523 05/08/2021 Winchelsea Cricket Ground And Pavilion, -

Spring Deals APRIL • MAY • JUNE • 2020

Spring Deals APRIL • MAY • JUNE • 2020 HEATING PACKS £89.99 £129.95 £125.00 HTGPACK1 HTGPACK2 HTGPACK3 Purchase any Joule product to be in with a chance to win a 43” 4K Ultra HD Smart Samsung TV HEATING PACK 1 - T3R HEATING PACK 2 - T4R HEATING PACK 3 - T6R HONEYWELL HOME RF 7 DAY PROG STAT HONEYWELL HOME RF 7 DAY PROG STAT HONEYWELL HOME SMART RF STAT INSTINCT MAGNETIC GREEN 15mm SCALE REDUCER HEATING - SCALEGREEN15 PACK PRICES FERNOX F1 PROTECTOR 265ML - FXF1265 INCLUDE FERNOX F3 CLEANER 265ML - FXF3265 WHILE £99.00 £89.00 HWSPLAN STOCKS HWYPLAN LAST Junction Box: FREE with these packs HONEYWELL HOME HONEYWELL HOME S PLAN PACK Y PLAN PACK 2 X TWO PORT MOTORIZED 22MM MID POSITION £49.95 HONEYWELL HOME Y87RF2024 VALVES, ST9400A, CYL STAT, MOTORIZED VALVE, ST9400A, ROOM STAT CYL STAT, ROOM STAT SINGLE ZONE THERMOSTAT Automatic entry is for SPS customers only who purchase a Joule product between 1st April 2020 & 30th June 2020 Charing Egerton A28 M20 Hawkenbury Little Chart Staplehurst Hastingleigh Elham Speldhurst Pembury Matfield Smarden A264 Cowden Copthorne Fordcombe Royal A21 Horsmonden Curtisden Frittenden A22 Green Holtye Tunbridge Chilmington Langton Green A2070 Lyminge East Grinstead Wells Bethersden Brabourne Crawley Down Green M20 A21 A229 Lees Biddenden Kingsnorth A22 Goudhurst A20 Crawley A26 Sissinghurst A20 Turners Hill Shadoxhurst Sellindge Hartfield High Halden Forest Row Frant Cranbrook M20 A264 Hook Green Kilndown Aldington A229 St Michaels Folkestone Bonnington West Hoathly Lympne A259 Sandgate Woodchurch A2070 Hythe -

Brightling and the Fullers

BRIGHTLING AND THE FULLERS A favourite hobby of authors is to write accounts of English eccentrics. Their books are many and they can be very entertaining. It is rarely that they do not include among their examples one ‘Mad Jack’ Fuller of Brightling Park. It may be as difficult to define eccentric as psychiatrists have found it in respect of abnormal, and clearly Jack was not mad – at least not compared with his contemporary John Mytton of Shropshire (whose extraordinary behaviour is not to be explored here). He was not really eccentric, either: he was just so independent of mind that he tended to veer from the conventional picture of the wealthy landowner. Locally John Fuller (1757-1834) is now known mainly for his extensions to Brightling Park (which he and his father called Rose Hill after his grandmother’s family name) and nationally for his benevolence to scientific researchers, but the ‘eccentrics’ authors can find out much more. A story goes that in London he argued with a friend that he could see Dallington church from his house; on his return home he found that he could not, so he built the forty- foot Sugar Loaf Folly in the right direction to give the impression that he was right. One hopes that he told his friend the truth. And on his death he declined to be buried. Along the lines of the traditional song On Ilkley John Fuller, by Henry Singleton. From https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/18791 Moor baht ‘at he took the view that worms would eat him; ducks would eat the worms; his family would eat the ducks.