Brightling and the Fullers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War One: the Deaths of Those Associated with Battle and District

WORLD WAR ONE: THE DEATHS OF THOSE ASSOCIATED WITH BATTLE AND DISTRICT This article cannot be more than a simple series of statements, and sometimes speculations, about each member of the forces listed. The Society would very much appreciate having more information, including photographs, particularly from their families. CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 The western front 3 1914 3 1915 8 1916 15 1917 38 1918 59 Post-Armistice 82 Gallipoli and Greece 83 Mesopotamia and the Middle East 85 India 88 Africa 88 At sea 89 In the air 94 Home or unknown theatre 95 Unknown as to identity and place 100 Sources and methodology 101 Appendix: numbers by month and theatre 102 Index 104 INTRODUCTION This article gives as much relevant information as can be found on each man (and one woman) who died in service in the First World War. To go into detail on the various campaigns that led to the deaths would extend an article into a history of the war, and this is avoided here. Here we attempt to identify and to locate the 407 people who died, who are known to have been associated in some way with Battle and its nearby parishes: Ashburnham, Bodiam, Brede, Brightling, Catsfield, Dallington, Ewhurst, Mountfield, Netherfield, Ninfield, Penhurst, Robertsbridge and Salehurst, Sedlescombe, Westfield and Whatlington. Those who died are listed by date of death within each theatre of war. Due note should be taken of the dates of death particularly in the last ten days of March 1918, where several are notional. Home dates may be based on registration data, which means that the year in 1 question may be earlier than that given. -

De Sussex Spaniel

Meesterwerk Tekst en illustraties: Ria Hörter Augustus Elliot Fuller (1777-1857) De Sussex Spaniel In Meesterwerk stellen we hondenrassen voor die zonder die ene fokker niet zouden bestaan. Dit keer is die fokker een steenrijke Engelse landeigenaar, woonachtig in Sussex, Wales en Londen en eigenaar van overzeese bezittingen. Zijn negentiende eeuwse ’Rose Hill’ Spaniels staan model voor de huidige Sussex Spaniels... Zwaar werk die rond 1795 aanwijsbaar begint met voorlopers. Het verhaal van de Sussex Vrijwel iedere kynologische auteur het fokken van Spaniels voor de jacht. Spaniel begint – hoe kan het anders – gaat er van uit dat Augustus Elliot (ook Spaniels die we vandaag de dag als in het Engelse graafschap Sussex, in gespeld Eliot, Eliott of Elliott) Fuller Sussex Spaniels betitelen of die we zuidoost Engeland. De Sussex Spaniel één van de eersten, zo niet de eerste, is tenminste kunnen zien als hun vroege werd en wordt gefokt voor de jacht in • De afbeelding met Spaniels uit Sydenham Edwards’ ’Cynographia Brittannica’ (1799-1805). Vier Spaniels in de kleuren lever en wit, zwart en wit, zandkleurig lever en lemon en wit. Getekend in de periode dat Augustus Fuller begint met de fokkerij van Sussex Spaniels. 64 Onze Hond 10 | 2010 Meesterwerk de dichte begroeiing op de zware kleigronden in dit graafschap. Niet zo maar een Spaniel, maar een zwaarge- bouwde hond voor zwaar werk. Squire De familie Fuller heeft haar wortels in Uckfield en Waldron (oost Sussex). De oudste Fuller die ik heb kunnen vinden is John Fuller, een rechtstreekse voorvader van Augustus Elliot, die in 1446 in Londen wordt geboren. -

Roads in the Battle District: an Introduction and an Essay On

ROADS IN THE BATTLE DISTRICT: AN INTRODUCTION AND AN ESSAY ON TURNPIKES In historic times travel outside one’s own parish was difficult, and yet people did so, moving from place to place in search of work or after marriage. They did so on foot, on horseback or in vehicles drawn by horses, or by water. In some areas, such as almost all of the Battle district, water transport was unavailable. This remained the position until the coming of the railways, which were developed from about 1800, at first very cautiously and in very few districts and then, after proof that steam traction worked well, at an increasing pace. A railway reached the Battle area at the beginning of 1852. Steam and the horse ruled the road shortly before the First World War, when petrol vehicles began to appear; from then on the story was one of increasing road use. In so far as a road differed from a mere track, the first roads were built by the Roman occupiers after 55 AD. In the first place roads were needed for military purposes, to ensure that Roman dominance was unchallenged (as it sometimes was); commercial traffic naturally used them too. A road connected Beauport with Brede bridge and ran further north and east from there, and there may have been a road from Beauport to Pevensey by way of Boreham Street. A Roman road ran from Ore to Westfield and on to Sedlescombe, going north past Cripps Corner. There must have been more. BEFORE THE TURNPIKE It appears that little was done to improve roads for many centuries after the Romans left. -

Kentish Weald

LITTLE CHART PLUCKLEY BRENCHLEY 1639 1626 240 ACRES (ADDITIONS OF /763,1767 680 ACRES 8 /798 OMITTED) APPLEDORE 1628 556 ACRES FIELD PATTERNS IN THE KENTISH WEALD UI LC u nmappad HORSMONDEN. NORTH LAMBERHURST AND WEST GOUDHURST 1675 1175 ACRES SUTTON VALENCE 119 ACRES c1650 WEST PECKHAM &HADLOW 1621 c400 ACRES • F. II. 'educed from orivinals on va-i us scalP5( 7 k0. U 1I IP 3;17 1('r 2; U I2r/P 42*U T 1C/P I;U 27VP 1; 1 /7p T ) . mhe form-1 re re cc&— t'on of woodl and blockc ha c been sta dardised;the trees alotw the field marr'ns hie been exactly conieda-3 on the 7o-cc..onen mar ar mar1n'ts;(1) on Vh c. c'utton vPlence map is a divided fi cld cP11 (-1 in thP ace unt 'five pieces of 1Pnii. THE WALDEN LANDSCAPE IN THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTERS AND ITS ANTECELENTS Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London by John Louis Mnkk Gulley 1960 ABSTRACT This study attempts to describe the historical geography of a confined region, the Weald, before 1650 on the basis of factual research; it is also a methodological experiment, since the results are organised in a consistently retrospective sequence. After defining the region and surveying its regional geography at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the antecedents and origins of various elements in the landscape-woodlands, parks, settlement and field patterns, industry and towns - are sought by retrospective enquiry. At two stages in this sequence the regional geography at a particular period (the early fourteenth century, 1086) is , outlined, so that the interconnections between the different elements in the region should not be forgotten. -

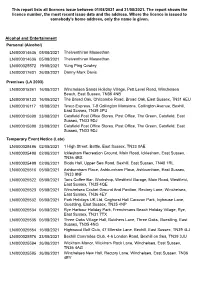

This Report Lists All Licences Issue Between 01/08/2021 and 31/08/2021. the Report Shows the Licence Number, the Most Recent Issue Date and the Address

This report lists all licences issue between 01/08/2021 and 31/08/2021. The report shows the licence number, the most recent issue date and the address. Where the licence is issued to somebody's home address, only the name is given. Alcohol and Entertainment Personal (Alcohol) LN/000014636 05/08/2021 Theiventhiran Maseethan LN/000014636 05/08/2021 Theiventhiran Maseethan LN/000025572 19/08/2021 Yung Ping Cowley LN/000017601 26/08/2021 Danny Mark Davis Premises (LA 2003) LN/000015241 16/08/2021 Winchelsea Sands Holiday Village, Pett Level Road, Winchelsea Beach, East Sussex, TN36 4NB LN/000016123 16/08/2021 The Broad Oak, Chitcombe Road, Broad Oak, East Sussex, TN31 6EU LN/000016117 18/08/2021 Tesco Express, 7-8 Collington Mansions, Collington Avenue, Bexhill, East Sussex, TN39 3PU LN/000015690 23/08/2021 Catsfield Post Office Stores, Post Office, The Green, Catsfield, East Sussex, TN33 9DJ LN/000015690 23/08/2021 Catsfield Post Office Stores, Post Office, The Green, Catsfield, East Sussex, TN33 9DJ Temporary Event Notice (Late) LN/000025496 02/08/2021 1 High Street, Battle, East Sussex, TN33 0AE LN/000025498 02/08/2021 Icklesham Recreation Ground, Main Road, Icklesham, East Sussex, TN36 4BS LN/000025499 02/08/2021 Blods Hall, Upper Sea Road, Bexhill, East Sussex, TN40 1RL LN/000025516 05/08/2021 Ashburnham Place, Ashburnham Place, Ashburnham, East Sussex, TN33 9NF LN/000025522 05/08/2021 Taris Coffee Bar, Workshop, Westfield Garage, Main Road, Westfield, East Sussex, TN35 4QE LN/000025523 05/08/2021 Winchelsea Cricket Ground And Pavilion, -

Spring Deals APRIL • MAY • JUNE • 2020

Spring Deals APRIL • MAY • JUNE • 2020 HEATING PACKS £89.99 £129.95 £125.00 HTGPACK1 HTGPACK2 HTGPACK3 Purchase any Joule product to be in with a chance to win a 43” 4K Ultra HD Smart Samsung TV HEATING PACK 1 - T3R HEATING PACK 2 - T4R HEATING PACK 3 - T6R HONEYWELL HOME RF 7 DAY PROG STAT HONEYWELL HOME RF 7 DAY PROG STAT HONEYWELL HOME SMART RF STAT INSTINCT MAGNETIC GREEN 15mm SCALE REDUCER HEATING - SCALEGREEN15 PACK PRICES FERNOX F1 PROTECTOR 265ML - FXF1265 INCLUDE FERNOX F3 CLEANER 265ML - FXF3265 WHILE £99.00 £89.00 HWSPLAN STOCKS HWYPLAN LAST Junction Box: FREE with these packs HONEYWELL HOME HONEYWELL HOME S PLAN PACK Y PLAN PACK 2 X TWO PORT MOTORIZED 22MM MID POSITION £49.95 HONEYWELL HOME Y87RF2024 VALVES, ST9400A, CYL STAT, MOTORIZED VALVE, ST9400A, ROOM STAT CYL STAT, ROOM STAT SINGLE ZONE THERMOSTAT Automatic entry is for SPS customers only who purchase a Joule product between 1st April 2020 & 30th June 2020 Charing Egerton A28 M20 Hawkenbury Little Chart Staplehurst Hastingleigh Elham Speldhurst Pembury Matfield Smarden A264 Cowden Copthorne Fordcombe Royal A21 Horsmonden Curtisden Frittenden A22 Green Holtye Tunbridge Chilmington Langton Green A2070 Lyminge East Grinstead Wells Bethersden Brabourne Crawley Down Green M20 A21 A229 Lees Biddenden Kingsnorth A22 Goudhurst A20 Crawley A26 Sissinghurst A20 Turners Hill Shadoxhurst Sellindge Hartfield High Halden Forest Row Frant Cranbrook M20 A264 Hook Green Kilndown Aldington A229 St Michaels Folkestone Bonnington West Hoathly Lympne A259 Sandgate Woodchurch A2070 Hythe -

Culture Curiosities Coast A23 Battle B2089 A26 A22 A259 Rye Calais

Updated Summer 2013 East Sussex inside & out How to get here By Train: Trains depart from London Charing Cross, By Road: Rye is situated on the A259 between London Bridge, St Pancras (High Speed Link) and Hastings to the west and Folkestone to the east and Waterloo East (change at Ashford International for on the A268 from the north. Visit www.theaa.co.uk Rye) approx 1hr 5mins. Trains also depart from London for a detailed route planner to Rye from your starting Victoria and Gatwick Airport (change at Hastings for destination. From London/M25, take the A21 or M20 Rye). Rail information: 08457 484950 and follow signs to Rye. Upon arrival, follow signs to www.nationalrail.co.uk Rye’s main visitor car park, Gibbet Marsh (210 spaces). M25 M20 Ramsgate LONDON M2 Ramsgate - Oste M26 nd A228 Canterbury M25 Maidstone A21 A28 M20 A2 M23 Tonbridge Gatwick A259 Ashford Dover Tunbridge A28 Wells A262 Dover - A22 A26 B2086 A2070 Dunkirk Folkestone A268 Tenterden A259 Channel e A21 Tu A28 A268 nnel Culture Curiosities Coast A23 Battle B2089 A26 A22 A259 Rye Calais over - Diepp D A27 A27 A259 Hastings Brighton Bexhill Newhaven Eastbourne Boulogne 1066 Country Newhaven - Dieppe www.visit1066country.com/rye www.rye-sussex.co.uk Dieppe The Inside & Out of Rye Historic Rye Writers and Artists Outside Rye Perched on a hill, the medieval town of Rye is the Whereas many towns boast a colourful past but Many of these Rye residents have become world Walks wind their way through the historic sort of place you thought existed only in your have little evidence of it, Rye can bear testimony to famous literary heroes, such as Henry James, landscape full of special wildlife, which can be imagination. -

Robertsbridge Circular Via Brightling

1st walk check 2nd walk check 1st June 2014 24th October 2015 Current status Document last updated Saturday, 26th January 2019 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: * The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. * Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. * This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. * All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2014-2019, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk The publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Robertsbridge Circular via Brightling Start and finish: Robertsbridge station Length: 18.3km (11.4 miles). Time: 5½ hours. For the whole outing, including trains, sights and meals, allow at least 8 hours. Transport: Trains go from London Charing Cross to Robertsbridge, journey time 1¼ hours. If finishing at Battle buy a day return to Battle otherwise a day return to Robertsbridge. OS Landranger Map: 199 OS Explorer Map: 124 Robertsbridge, map reference TQ733235 is East Sussex 22km south-east of Tunbridge Wells. Toughness: 3 out of 10. -

Ww2 Civilian Deaths in and from the Battle District

WW2 CIVILIAN DEATHS IN AND FROM THE BATTLE DISTRICT Records show that 17 civilians in or from the Battle district died as a result of enemy action in the Second World War. The total for the whole country was about 40,000. This otherwise peaceful area had no industries worth bombing but nevertheless suffered along with the rest of the country – though to a much lesser extent than most of the cities and large towns. This was partly due to its being beneath the bombers’ flight path when they rid themselves of undropped bombs on the way home. If in the First World War those who stayed behind in the Battle district were in negligible danger of an early death this would not be true of the later war: nowhere in the UK was safe from enemy attack, regardless of age – and our own dead ranged from 14 months to 77 years. Details are hard to find because the newspapers of the day were properly restrained from reporting anything that would give help to the enemy or harm local morale. However, the overall position is known from a report of August 1945 which, being unofficial, may not be wholly accurate.1 For the area with which this account is concerned the bombing was, in brief: Notes: HE = high explosive; unexpl = unexploded; MG = machine gun. Blank = 0. V1 High explosive Incendiary Oil MG Civilians Dropped Unexpl etc attacks Killed Injured Ashburnham 7 67 3 740 3 2 3 Battle 27 69 32 55 5 1 2 32 Brede 26 Brightling 4 Bodiam 1 Catsfield 5 16 2 720 4 5 Crowhurst 4 20 14 602 4 18 Dallington 10 31 4 176 4 Ewhurst 9 Mountfield 19 24 1066 1 14 Penhurst 1 Ninfield * Salehurst/Robertsbridge 10 22 1 2 5 Sedlescombe 7 18 2 886 2 Westfield 12 20 4 33 6 Whatlington 3 21 16 900 6 Total 105 308 78 5178 13 3 8 95 Ninfield does not appear in the list in this source. -

![Brightling - Little Sprays [P8/1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5728/brightling-little-sprays-p8-1-1905728.webp)

Brightling - Little Sprays [P8/1]

BRIGHTLING - LITTLE SPRAYS [P8/1] Tenement called Reeds & Hoadland. DETAILS OF PROPERTY <1653-1842+ Ho, Bn + c.36a. Described in a deed of 1653 as a messuage + 38 acres called Reeds & Hoadlands in Brightling & Dallington [3] Described in a deed of 1746 as a messuage, barn, malthouse + 38a called Reeds & Hoadlands [3]. The Tithe award of 1839 describes that part in Brightling parish as comprising a house, buildings + 19a.3r.39p. called Little Sprays als Sindens Farm [4] + 15a. in Dallington parish [5]. Total = 34a.3r.39p. DETAILS OF HOUSE 17th C? House built The house has not been viewed internally, but it appears to be of 17th century or earlier origin, extended later. 1662-5 House assessed @ 2 flues Thomas Sheather was assessed in hearth tax at 2 flues for this property [8]. DETAILS OF BARN 17th C Barn built. Barn surveyed by ROHAS in 1979. It is a three bay structure, set at right angles & in front of the house, dates from the 17th century - for details see ROHAS Report No. 464. POOR RATE ASSESSMENT 1663 £6 <for that part in Brightling Parish only> [7]. LAND TAX ASSESSMENTS - BRIGHTLING [1] 1702-1725 £6. 1735-1765 £7:5:0 1775-1839 £7. LAND TAX ASSESSMENTS - DALLINGTON [2] 1711-1840 £2. Called 'late Fowles' or 'Fowles Field'. DETAILS OF OWNERSHIP <1605-1605+ John Cressy [9] <1653-1653+ Anne Pilcher, spinster In 1653 she barred an entail on the property [3]. <1671-1727 Gyls Watts, Gent. Watts was already the owner by 1671 [6]. He was of Battle in 1725 when he made a settlement of this farm (with other property) on self for life with remainder to his wife Jane (only daughter & heir of James Relfe of Battle, Gent., dec.) [3]. -

Secret Sussex an Unusual Guide

ELLIE SEYMOUR SECRET SUSSEX AN UNUSUAL GUIDE JONGLEZ PUBLISHING CHICHESTER TO PETWORTH BLAKE’S COTTAGE 10 aving created some of the most iconic and influential works A seminal Romantic artist’s former seaside Hof British art and poetry, William Blake, the English painter, retreat printmaker and poet, is now recognised as a seminal figure of the Romantic Age. Blakes Road According to the Blake Society, he lived in nine houses in his Felpham, Bognor Regis, West Sussex, PO22 7EE lifetime, only two of which survive: one in London’s West End at 17 To view from the outside only South Molton Street, and this one in the village of Felpham in Bognor Regis, West Sussex. In 1800, Blake moved from Lambeth in south London into this humble thatched cottage on the Sussex coast with his wife, Catherine, to escape the city and take up a job illustrating books. The move also marked the start of the most important period in Blake’s life and career. It was in this cottage that he wrote some of his best-known poetic works, including Milton: A Poem and the words to the hymn Jerusalem. He also depicted the cottage several times in his paintings; for instance, in a rare watercolour landscape showered in sunlight, now held by the Tate Britain. He is also known to have described the house in letters to a friend: “No other house can please me so well, nor shall I ever be persuaded, I believe, that it can ever be improved in beauty or use ... the sweet air and the voices of winds, trees, and birds, and the odours of the happy ground, make it a dwelling for immortals. -

Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society Newsletter Number 159 July 2013

Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society - Newsletter Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society Newsletter Number 159 July 2013 Singleton goods shed being examined by SIAS members on the occasion of the Society’s visit on 3 May 2008. This shows the north (track) side of the building with the typical Myres mock-timbering and pargetting. The goods office is to the right. Do not miss the article on the recent listing and history of this building. (Alan Green) 1 Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society - Newsletter Newsletter 159 Contents July 2013 Editorial ..........................................................................................................2 Forthcoming SIAS Events ............................................................................. 3 Events from Other Societies ..........................................................................4 SERIAC 2013 ................................................................................................ 7 Endangered Sites ........................................................................................... 9 Sussex Garage Listed .................................................................................. 10 The Railway Buildings of T. H. Myers ........................................................ 11 Book Review ............................................................................................... 19 Mad Jack Fuller ........................................................................................... 20 Changing Countryside .................................................................................