Bhavnagar State Census, Report, Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

C:\Users\ACCER\Desktop\JULY QUESTION LIST\Final Make\Final

LOK SABHA ______ List of Questions for ORAL ANSWERS Wednesday, August 11, 2021/Sravana 20, 1943 (Saka) ______ (Prime Minister; Ministries of Atomic Energy; Coal; Commerce and Industry; Communications; Defence; Development of North Eastern Region; Electronics and Information Technology; External Affairs; Law and Justice; Mines; Parliamentary Affairs; Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions; Planning; Railways; Space; Statistics and Programme Implementation) (¯ÖϬÖÖ®Ö ´ÖÓ¡Öß; ¯Ö¸ü´ÖÖÞÖã ‰ú•ÖÖÔ; ÛúÖêµÖ»ÖÖ; ¾ÖÖ×ÞÖ•µÖ †Öî¸ü ˆªÖêÝÖ; ÃÖÓ“ÖÖ¸ü; ¸üõÖÖ; ˆ¢Ö¸ü ¯Öæ¾Öá õÖê¡Ö ×¾ÖÛúÖÃÖ; ‡»ÖꌙÒüÖò×®ÖÛúß †Öî¸ü ÃÖæ“Ö®ÖÖ ¯ÖÏÖîªÖê×ÝÖÛúß; ×¾Ö¤êü¿Ö; ×¾Ö×¬Ö †Öî¸ü ®µÖÖµÖ; ÜÖÖ®Ö; ÃÖÓÃÖ¤üßµÖ ÛúÖµÖÔ; ÛúÖÙ´ÖÛú, »ÖÖêÛú ׿ÖÛúÖµÖŸÖ †Öî¸ü ¯Öë¿Ö®Ö; µÖÖê•Ö®ÖÖ; ¸êü»Ö; †ÓŸÖ׸üõÖ; ÃÖÖÓ×ܵÖÛúß †Öî¸ü ÛúÖµÖÔÛÎú´Ö ÛúÖµÖÖÔ®¾ÖµÖ®Ö ´ÖÓ¡ÖÖ»ÖµÖ) ______ Total Number of Questions — 20 VIP References authority empowered to act against companies *321. SHRIMATI SANGEETA KUMARI SINGH following unethical business models and infringing on DEO: the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) norms in the country, SHRI BHOLA SINGH: particularly in e-commerce sector and if so, the details thereof; Will the Minister of RAILWAYS ¸êü»Ö ´ÖÓ¡Öß (b) whether the Government proposes to set up a be pleased to state: regulatory authority for the e-commerce sector in the (a) whether VIP references for release of HO quota country and if so, the details thereof; by the Ministry of Railways/Indian Railways/Zones are (c) whether the Government proposes to not being given priority in recent times; bring in a national -

WRC for Website.Xlsx

List of TEIs recognized by WRC, NCTE as on 31.03.2019 S.No. Application ID Name & Address of the Institutions State Management Course and Intake BHARTIYANAGAR EDUCATION TRUST HIRABA B.ED. COLLEGE FOR 1 APW0243 8/323268 Gujarat PRIVATE B.Ed. 100 WOMEN, C/O DAFNALA ROAD, SHAHIBAUG, AHMEDABAD, GUJARAT BHAVNA B.ED. COLLEGE SHANTASHIV EDUCATION TRUST, PLOT NO.- 66, APW02609 2 RAJPATNAGAR, OPP. GOVERNMENT. WELL, TAL-DASCROI BOPAL, Gujarat PRIVATE B.Ed. 100 / 323304 AHMEDABAD , AHMEDABAD, GUJARAT DISTRICT INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING AHMEDABAD PLOT NUMBER : 464-465, VILLAGE : GOTA, POST OFFICE : 3 APP2876 GUJARAT HIGHCOURT POST OFFICE, TEHSIL/TALUKA:DASCROI,DISTRICT Gujarat GOVERNMENT B.Ed. 50 : AHMEDABAD – 380060,GUJARAT. APW01359 HIRALAL BAPULAL KAPADIA COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, H.B. KAPADIA / 323211/ EDUCATION TRUST, THE NEW HIGH SCHOOL CAMPUS, RATAN POLE, PIR 4 APW05561 MOHAMMED SHAH ROAD, AHMEDABAD- 380001 Gujarat PRIVATE B.Ed. 200 / 323211 (addl.)/ I.D.PATEL COLLEGE OF EDUCATION I.D.PATEL EDUCATION CAMPUS, APW02623 5 MATRUKRUPA EDUCATION & CHERATIBLE TRUST,OPP. NIRMAN TOWER, NR. Gujarat PRIVATE B.Ed. 50,D.El.Ed. 50 / 323308 VISHVAS CITY, GHATLODIA, AHMEDBAD-380061 GUJARAT JANJAGRATI SEVA SAMITI KRITEETI B.ED. COLLEGE, PATANJALI SOCIETY, 6 APW04437/ 323435 Gujarat PRIVATE B.Ed. 100 KHODIYAR NAGAR, AHMEDBAD GUJARAT-382350 JG COLLEGE OF EDUCATION JG CAMPUS OF EXCELLENCE, OPP. GULAB APW00254 7 TOWER, OFF. GULAB TOWER, GHATLODIA, DISTRICT-AHMEDBAD- 380061 Gujarat PRIVATE B.Ed. 100 / 323055 GUJARAT K.M. PATEL COLLEGE OF EDUCATION SHAKTI EDUCATION TRUST, APW02624 8 PLOT NO. 229, TP. NO. 2, GHATLODIA, DIST. – AHMADABAD 380061, GUJARAT Gujarat PRIVATE B.Ed. 100 / 323309 KAMESHWAR COLLEGE OF EDUCATION NEAR ANAND NAGAR, 100 FT. -

IJRESS Volume 1, Issue 1 (October, 2011) (ISSN 2249-7382) International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences

IJRESS Volume 1, Issue 1 (October, 2011) (ISSN 2249-7382) International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences MONTHLIES AND EWS PAPERS: THEIR IMPACT ON SOCIAL LIFE OF KATHIAWAD (1851-1910) Dilip Chaudhary Asst. Prof. P.G.Dept. of History, Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar. Dist.:Anand INTRODUCTION Establishment of political agency was done at Rajkot in 1822 A.D. after getting rights of Peshwa and Gaekwad governments to British East India Company in 1820 A.D. [1] From this time, British East India Company Government took over management of Kathiawad. Before that, kings, Thakors and Talukadars of Kathiawad – Saurashtra and people under their reign became free from invasions of territory and mutual wars due to walker agreement in 1807 A.D. and they got promise f peaceful development for long time. [2] As a result, social disorder, mis-organization and restless wars ended. There was a dawn of happiness, peace and prosperity. [3] Now time was changed, works were done by swords and money before, now were to be done by pen and shrewdness. Time was came to do organizational and internal reformations leaving occupying of new regions. Direct reign of British was established after revolt of 187 A.D. Movement of social-religious reformations had also played an important role in impacting wide region of Kathiawad. Kathiawad peninsula is situated between 20.400 to 23.250 north latitude and 69.50 to 70.200 east longitudes. [4] Its length from Bhavnagar to Dwarka is 352 kms and breadth from Zinzuwada in North and Div Island in South is 264 kms. -

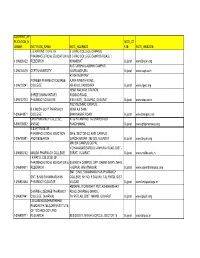

Quarantine Centres in Gujarat Name of Hotel/ Room Contact Quaranti Rate(Includ Person(Gov Sl

Quarantine Centres in Gujarat Name of Hotel/ Room Contact Quaranti Rate(includ Person(Gov Sl. ne ing meals Contact Person Contact t. official in No. District Type: Centre: Email Phone and taxes) (Hotel/Centre) Number Charge) Contact no. Remarks 1 GANDHINAG On Yatri Inn nrgfounda 9898111112 Category Mr. Jitendra 9898111112 N.S.Salvi, 9978405243 Note: AR Payment tion@yah 1:1500 Patel Executive Taxes and oo.co.in engineer, food charges are extra. 2 MAHESANA On Gratis Yatri nrgfounda 9978259072 Category Jayantibhai 9978259072 SHRI 8511231433 Bhavan, tion@yah 1:0 Joitaram Patel B.J.BHARW oo.co.in AD 3 Mahisagar On Vrundav nrgfounda 9426575806 Category Manager 9426575806 Ms. Neha 9978405954 Note: Payment an Hotel tion@yah 1:900 Gupta Taxes are oo.co.in Category extra. 2:900 4 RAJKOT On Gratis Vrajbho nrgfounda 7567009541 Category Mr.G.V.Miyani,P 7567009541 SHRI 9909970214 omi tion@yah 1:0 rant R.S.UPADHY Aashram oo.co.in Officer,Dhoraji AY , 5 NARMADA On Vraj nrgfounda 9099943335 Category Dr. Kashyap 9099943335 Dr. Kashyap 9099943335 Note: GST Payment Hotel tion@yah 1:3000 extra. Rajpipla oo.co.in 6 MORBI On Vibhav nrgfounda 9879444680 Category Himanshubhai 9879444680 Harshaben 9827558330 Note: Payment Hotel tion@yah 1:1500 Patel Taxes are oo.co.in extra. For AC- +Food Rs.3000/- 7 RAJKOT On Gratis Vataliya nrgfounda 7990147421 Category Mr.Charansinh 7990147421 SHRI 9909970214 Prajapati tion@yah 1:0 Gohil,Prant R.S.UPADHY Samaj oo.co.in officer,Rajkot AY Vadi City-2 &a mp; Chhatral aya 8 RAJKOT On Gratis Vataliya nrgfounda 7990147421 Category Mr.Charansinh 7990147421 SHRI 9909970214 Prajapati tion@yah 1:0 Gohil R.S.UPADHY Samaj oo.co.in AY Vadi & Chhatral aya 9 GANDHINAG On Varun nrgfounda 9624066786 Category Mr. -

Thursday, July 11, 2019 / Ashadha 20, 1941 (Saka) ______

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES* (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Thursday, July 11, 2019 / Ashadha 20, 1941 (Saka) ______ SUBMISSION BY MEMBERS Re: Farmers facing severe distress in Kerala. THE MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI RAJ NATH SINGH) responding to the issue raised by several hon. Members, said: It is not that the farmers have been pushed to the pitiable condition over the past four to five years alone. The miserable condition of the farmers is largely attributed to those who have been in power for long. I, however, want to place on record that our Government has been making every effort to double the farmers' income. We have enhanced the Minimum Support Price and did take a decision to provide an amount of Rs.6000/- to each and every farmer under Kisan Maan Dhan Yojana irrespective of the parcel of land under his possession and have brought it into force. This * Hon. Members may kindly let us know immediately the choice of language (Hindi or English) for obtaining Synopsis of Lok Sabha Debates. initiative has led to increase in farmers' income by 20 to 25 per cent. The incidence of farmers' suicide has come down during the last five years. _____ *MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 1. SHRI JUGAL KISHORE SHARMA laid a statement regarding need to establish Kendriya Vidyalayas in Jammu parliamentary constituency, J&K. 2. DR. SANJAY JAISWAL laid a statement regarding need to set up extension centre of Mahatma Gandhi Central University, Motihari (Bihar) at Bettiah in West Champaran district of the State. 3. SHRI JAGDAMBIKA PAL laid a statement regarding need to include Bhojpuri language in Eighth Schedule to the Constitution. -

Four Lanning Rajkot-Bhavnagar (Total Length 52.40 Km Road

devmediator/Raikot/Zala Forest atkot-29 1 0201 4 Name of work :: Four Lanning Rajkot-Bhavnagar road between Km. 7l2O to 59/60 (Section-l- and,-ll-) of Rajkot District. (Total length 52.40 Km Annexure-7 :: DETAILED NOTE ON THE PROJECT :: As this is joining to head quarters of Rajkot. Jasdan, Babra, Dhasa and finally meets to Bhavnagar District. and also very important road due to vast development of Chemical and Cement Industry at Kovaya, Rajula, and Alang Sheep Breaking Yard @ Bhavnagar. Moreover Small scale and Diarnond Industry at Jasdan and Babra is growing up widely and for Transporting of all these prcducts, Dairy and Agricultural Product to Nearest Market yard of Jasdan, Babra ot Dhata. The Rural public have to come @ Rajkot, Amreli or Bhavnagar for their business and jobs. this is the short route for all thype of vehicles and about 56-villages getting advantage of this road. As per A"A. there is provision of Widening of this road to Standard Four lane carriage way width as such Forest Land will be required hence this proposal is submitted for its approval at competent level. This is an imporlant road joining to Arr-rreli, Bhavnagar and Ahmedabad (Start frorn Rajkot) to Atkot, Babra. Sihor, Sanosara via Atkot and Babra rvhere the Atkot is a.Tunction place from r,vhere the road is bifurcated over the Raikot-Bhavnagar and Amreli rvhere the Rajkot is the biggest Industrial areq and Bhavnagar is also having Mega Sheep breaking Industry and Amreli is hai,ing Cement Industry at Rajula (Kovaya) and part of Gir Foresty at Dhari and Tulsishyarn So this road plays an important route in development of Rajkot/Amreli and Bhavnagar Districts in Industrial/Agricultural as rvell as Pilgrimage center of Palitana and Khoclil,ar Temple on this road. -

District Census Handbook, Bhavnagar, Part XIII-A & B, Series-5

CENSUS 1981 PARTS XIII-A & B TOWN & VILLAGE DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE SERIES-5 PRIMARY CENSUS GUJARAT ABSTRACT BHAVNAGAR DISTRICT DISTRICT' CENSUS HANDBOOK R. S. CHHAYA of the Indian Administrative Servico Director of Census Operations Gujara,t CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 LIST OF PROPOSED PUBLICATIONS Central Government Publications Census of India, 1981 Series 5-Gujarat is being published in the following parts Part Subject Covered Number :I-A Administration Report-Enumeration I-B Administration Report-Tabulation II-A General PopUlation Tables ·II-B General Population Tables - Primary Census Abstract III-A General Economic Tables - B-Series (Tables B-1 to B-lO) III-B General Economic Tables - B-Series (Tables B-11 to B-22) IV-A Social and Cultural Tables - C-Series (Tables C-l to C-6) IV-B Social and Cultural Tables - C-Series (Tables C-7 to C-IO) V-A Migration Tables - D-Series (Tables D-l to D-4) V-B Migration Tables - D-Series (Tables D-5 to D-13) VI-A Fertility Tables - F-Series (Tables F-I to F-19) VI-B Fertility Tables - F-Series (Tables F-20 to F-28) ·VII Tables on Houses and Disabled Population VIII-A Household Tables (Tables HH-l to HH-16) VUI-B Household Tables (Tables HH-17) VIII-C 'Report on Households IX Special Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes X-A Town Directory X-B Survey Reports on Selected Towns X-C Survey Reports on Selected Villages XI Ethnographic Notes and Special Studies on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribe! XII Census Atlas DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOKS XIII-A Village and Town Directory XIII-B Village and Townwise Primary Census Abstract * Published t Under Print Note: (I) All the maps included in this publication are based upon Surveyo.· f India map with the permission of the Surveyor. -

Gaorishankar Udayashankar, G.S.I., Ex-Minister of Bhavnagar, Now In

B II A V N A G A II ARTHUR PROBSTHAIN Oriental Bookseller 41 Gt. Runel! Street LONDO N. W.C. I UCS0 LIBRARY liAORISHAMAR UDAYASHANKAR, C.S.I., NOW IN RETIREMENT AS A SANYiSI. JAVERILAL UMIAHANKAR YAJNIK. Lives of great men all remind us We can make our lives sublime ; And, departing, leave behind us Footprints on the sands of time. LONGFELLOW. o b a : $ m ]t PRINTED AT THP: EDUCATION SOCIETY'S PRESS, BYCULLA. INTRODUCTORY NOTE. FOR some time past it has been felt by the friends of Mr. Gaorishankar, European as well as Native, that it would be" desirable to have some record of his life and work. In compliance with this desire, I undertook to compile a short account of him from such materials as were available to me. These were not so full and ample as I could have desired. They were wanting in that essential element which gives its chief interest to a work of biography, namely, private correspondence. On this account nobody is more sensible than I am of the imperfect nature of the present sketch, and my only reason for permitting its publication is that it is better to have some record, however wanting in fulness, of the work done by the first living statesman of Kathiawad, now in retirement as a Sanyasi, than to have none at all. Since writing this sketch, however, I am glad to say that my friends, Messrs. Vajeshankar and Prabhashankar, the two worthy sons of Mr. Gaorishankar, have, at my suggestion, undertaken to arrange systematically the whole of the correspondence, records, and papers, in in of the English and Gujarat i, which are the possession family, and may serve to elucidate the career of their illustrious father. -

Of 77 OPEN E-TENDER TSV Services CIN No

OPEN E-TENDER TSV Services CIN No. L74899DL1999GOI101707 Website: www.irctc.com Email id: [email protected] OPEN E-TENDER BID DOCUMENT FOR PROVISION OF ONBOARD CATERING SERVICES THROUGH TRAIN SIDE VENDING (TSV), IN IDENTIFIED MAIL / EXPRESS / SUPER FAST TRAINS, RUNNING WITHOUT PANTRY CAR, IN PARTIAL / COMPLETE UNBUNDLING MODEL IN FOLLOWING SECTIONS Sec. No. TSV Section Railway I CSMT-Daund-CSMT(Via Pune)/CSMT – Roha-CSMT/Roha-BSR-Roha Central Railway II DAUND-KOLHAPUR-DAUND/PUNE-KOLHAPUR-PUNE Central Railway III MMR-CSMT-MMR Central Railway IV MMR-/Wadi/Latur(Via DD)-MMR & KMV-MRJ-KMV Central Railway V MMR-BSL-MMR Central Railway VI BRC-MMCT-BRC, Western Railway IX Central/West Central Railway NGP-ET-NGP XI Jabalpur (JBP) – Katni (KTE) – Satna (STA) – Manikpur (MKP) / Rewa – Jabalpur West Central Railway (JBP) and Jabalpur (JBP) – Bina (BINA) - Jabalpur (JBP) Via Katni (KTE) XVI Western Railway ADI-VG-DHG-SIOB-GIMB-BHUJ & SIOB-PNU XVII Western Railway VG-SUNR-RJT- HAPA-JAM- KNLS-OKHA and WKR-MVI-DAC-MALB XVIII SUNR-DLJ-SOJN-PIT/BVP; SUNR-DLJ-RLA-MHV; PBR-WSJ-JLR-RJT; PBR- Western Railway WSJ-LPJ-KNLS-JAM-RJT(VIA HAPA)/OKHA(VIA KNLS); SMNH-VRL-JND- JLR-RJT/OKHA(Via WSJ) XIX BINA-ET-BINA West Central Railway XX JBP-ET-JBP West Central Railway XXI BSL-ET-BSL Central/West Central Railway Last date and Time of Submission of bids : 25-02-2020 by 1500 hrs Date and Time of Opening of bids : 25-02-2020 at 1530 hrs Pre-bid Meeting : 14-02-2020 at 1500 hrs E-Tender No. -

Current Ap Plication Umber N Institute Name Insti Address Insti St Ate Insti Website 1-396085422 L B Rao Institute of Pharmac

CURRENT_AP PLICATION_N INSTI_ST UMBER INSTITUTE_NAME INSTI_ADDRESS ATE INSTI_WEBSITE L B RAO INSTITUTE OF B D RAO COLLEGE CAMPUS, PHARMACEUTICAL EDUCATION & B D RAO COLLEGE CAMPUS ROAD, 1-396085422 RESEARCH KHAMBHAT Gujarat www.lbriper.org KASTURBHAI LALBHAI CAMPUS 1-396100415 CEPT UNIVERSITY NAVRANGPURA Gujarat www.cept.ac.in AT-SAYAJIPYRA PIONEER PHARMACY DEGREE AJWA-NIMETA ROAD 1-396103241 COLLEGE NR-N.H.8, VADODARA Gujarat www.ogect.org NEAR RAILWAY STATION, SHREE DHANVANTARY KUDSAD ROAD 1-396137213 PHARMACY COLLEGE KIM (EAST), TA-OLPAD, DI-SURAT Gujarat www.sdpc.co.in POLYTECHNIC CAMPUS, B.K.MODY GOVT.PHARMACY NEAR AJI DAM 1-396649871 COLLEGE BHAVNAGAR ROAD Gujarat www.bkmgpc.com GHB PHARMACY COLLEGE, AT & PO-ANIYAD,,, TA-SHAHERA,DI- 1-396708382 ANIYAD PANCHMAHAL Gujarat www.ghbpharmacy.org K.B.INTITUTE OF PHARMACEUTICAL EDUCTION GH/6, SECTOR-23, KADI CAMPUS, 1-396780981 AND RESEARCH GANDHINAGAR- 382 023, GUJARAT Gujarat www.kbiper.org MALIBA CAMPUS,GOPAL VIDYANAGAR,BARDOLI-MAHUVA ROAD, DIST - 1-396882142 MALIBA PHARMACY COLLEGE SURAT, GUJARAT Gujarat www.maliba.edu.in I.K.PATEL COLLEGE OF PHARMACEUTICAL EDUCATION & SAMARTH CAMPUS, OPP. SABAR DAIRY, NH-8, 1-396899501 RESEARCH HAJIPUR, HIMATNAGAR Gujarat www.samarthcampus.com SMT. B.N.B. SWAMINARAYAN PHARMACY SMT. B.N.B SWAMINARAYAN COLLEGE, NH NO. 8 SALVAV, TAL PARDI, DIST 1-396901664 PHARMACY COLLEGE VALSAD Gujarat www.bnbspcollege.in AMRAPALI TOWNSHIP, PETLAD-KHAMBHAT DHARMAJ DEGREE PHARMACY ROAD, DHARMAJ-388430 1-396907441 COLLEGE, DHARMAJ TA: PETLAD, DIST: ANAND, GUJARAT Gujarat www.ipcprc.org LEELABEN DASHRATHBHAI RAMDAS PATEL(LDRP)INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND 1-396908711 RESEARCH BESIDES ITI, NR KH 5 CIRCLE, SECTOR 15 Gujarat www.ldrp.ac.in KRISHNA KAMPUS, BECHRAJI-SHANKHALPUR SHREE KRISHNA INSTITUTE OF ROAD, TALUKA-BECHRAJI, DIST-MEHSANA, 1-396910173 PHARMACY GUJARAT Gujarat www.skip.org.in MEHSANA - VISNAGAR HIGHWAY, AT & PO.