The Laich O' Menteith: Reassessing the Origins of the Lake Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERTHSHIRE POST OFFICES (Updated 22/2/2020)

PERTHSHIRE POST OFFICES (updated 22/2/2020) Aberargie 17-1-1855: BRIDGE OF EARN. 1890 ABERNETHY RSO. Rubber 1899. 7-3-1923 PERTH. Closed 29-11-1969. Aberdalgie 16-8-1859: PERTH. Rubber 1904. Closed 11-4-1959. ABERFELDY 1788: POST TOWN. M.O.6-12-1838. No.2 allocated 1844. 1-4-1857 DUNKELD. S.B.17-2-1862. 1865 HO / POST TOWN. T.O.1870(AHS). HO>SSO 1-4-1918 >SPSO by 1990 >PO Local 31-7-2014. Aberfoyle 1834: PP. DOUNE. By 1847 STIRLING. M.O.1-1-1858: discont.1-1-1861. MO-SB 1-8-1879. No.575 issued 1889. By 4/1893 RSO. T.O.19-11-1895(AYL). 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 19-1-1921 STIRLING. Abernethy 1837: NEWBURGH,Fife. MO-SB 1-4-1875. No.434 issued 1883. 1883 S.O. T.O.2-1-1883(AHT) 1-4-1885 RSO. No.588 issued 1890. 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 7-3-1923 PERTH. Closed 30-9-2008 >Mobile. Abernyte 1854: INCHTURE. 1-4-1857 PERTH. 1861 INCHTURE. Closed 12-8-1866. Aberuthven 8-12-1851: AUCHTERARDER. Rubber 1894. T.O.1-9-1933(AAO)(discont.7-8-1943). S.B.9-9-1936. Closed by 1999. Acharn 9-3-1896: ABERFELDY. Rubber 1896. Closed by 1999. Aldclune 11-9-1883: BLAIR ATHOL. By 1892 PITLOCHRY. 1-6-1901 KILLIECRANKIE RSO. Rubber 1904. Closed 10-11-1906 (‘Auldclune’ in some PO Guides). Almondbank 8-5-1844: PERTH. Closed 19-12-1862. Re-estd.6-12-1871. MO-SB 1-5-1877. -

RESTAURANTS in the TROSSACHS ABERFOYLE Lake of Monteith Hotel & Waterfront Restaurant Port of Menteith FK8 3RA

RESTAURANTS IN THE TROSSACHS ABERFOYLE CALLANDER (Cont’d) EXPENSIVE Callander Meadows Restaurant Lake of Monteith Hotel & Waterfront Restaurant 24 Main Street Port of Menteith FK8 3RA Callander FK17 8BB Tel: 44 01877 385 258 Tel: 44 01877 330 181 www.lake-hotel.com/eat/restaurant.aspx Modern British cuisine http://www.callandermeadowsrestaurant.co.uk/ Open Thursday through Sunday BUDGET Traditional Scottish cuisine The Gathering INEXPENSIVE The Forth Inn Main Street The Old Bank Restaurant Aberfoyle FK8 3UK 5 Main Street Tel: 44 01877 382372 Callander FK17 8DU www.forthinn.com Tel: 44 01877 330 651 Traditional Scottish cuisine Open daily until 7:30pm. Coffee shop / restaurant CALLANDER DUNBLANE EXPENSIVE Mhor Fish EXPENSIVE 75 Main Street Cromlix House Callander FK17 8DX Kinbuck Tel: 44 01877 330 213 Dunblane FK15 9JT http://mhor.net/fish/ Tel: 44 01786 822 125 Open Tuesday through Sunday www.cromlixhouse.com/ Modern British cuisine BUDGET Located about ¼ hour north of Dunblane The Byre Inn Brig O’Turk INEXPENSIVE Near Callander FK17 8HT Tel: 44 01877 376 292 Clachan Restaurant www.byreinn.co.uk/ The Village Inn Traditional Scottish cuisine 5 Stirling Road Dunblane FK15 9EP Tel: 44 01786 826 999 http://thevillageinndunblane.co.uk/default.aspx Very popular local spot for pub grub and traditional Scottish cuisine © 2012 PIONEER GOLF ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PG092711 RESTAURANTS IN THE TROSSACHS (Cont’d) OBAN STIRLING (Cont’d) UPSCALE INEXPENSIVE Coast Mamma Mia 104 George Street 52 Spittal Street Oban PA34 5NT Stirling FK8 1DU Tel: 44 01786 -

Fnh Journal Vol 28

the Forth Naturalist and Historian Volume 28 2005 Naturalist Papers 5 Dunblane Weather 2004 – Neil Bielby 13 Surveying the Large Heath Butterfly with Volunteers in Stirlingshire – David Pickett and Julie Stoneman 21 Clackmannanshire’s Ponds – a Hidden Treasure – Craig Macadam 25 Carron Valley Reservoir: Analysis of a Brown Trout Fishery – Drew Jamieson 39 Forth Area Bird Report 2004 – Andre Thiel and Mike Bell Historical Papers 79 Alloa Inch: The Mud Bank that became an Inhabited Island – Roy Sexton and Edward Stewart 105 Water-Borne Transport on the Upper Forth and its Tributaries – John Harrison 111 Wallace’s Stone, Sheriffmuir – Lorna Main 113 The Great Water-Wheel of Blair Drummond (1787-1839) – Ken MacKay 119 Accumulated Index Vols 1-28 20 Author Addresses 12 Book Reviews Naturalist:– Birds, Journal of the RSPB ; The Islands of Loch Lomond; Footprints from the Past – Friends of Loch Lomond; The Birdwatcher’s Yearbook and Diary 2006; Best Birdwatching Sites in the Scottish Highlands – Hamlett; The BTO/CJ Garden BirdWatch Book – Toms; Bird Table, The Magazine of the Garden BirthWatch; Clackmannanshire Outdoor Access Strategy; Biodiversity and Opencast Coal Mining; Rum, a landscape without Figures – Love 102 Book Reviews Historical–: The Battle of Sheriffmuir – Inglis 110 :– Raploch Lives – Lindsay, McKrell and McPartlin; Christian Maclagan, Stirling’s Formidable Lady Antiquary – Elsdon 2 Forth Naturalist and Historian, volume 28 Published by the Forth Naturalist and Historian, University of Stirling – charity SCO 13270 and member of the Scottish Publishers Association. November, 2005. ISSN 0309-7560 EDITORIAL BOARD Stirling University – M. Thomas (Chairman); Roy Sexton – Biological Sciences; H. Kilpatrick – Environmental Sciences; Christina Sommerville – Natural Sciences Faculty; K. -

E-News Winter 2019/2020

Winter e-newsletter December 2019 Photos Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year! INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Contributions to our newsletters Dates for your Diary & Winter Workparties....2 Borage - Painted Lady foodplant…11-12 are always welcome. Scottish Entomological Gathering 2020 .......3-4 Lunar Yellow Underwing…………….13 Please use the contact details Obituary - David Barbour…………..………….5 Chequered Skipper Survey 2020…..14 below to get in touch! The Bog Squad…………………………………6 If you do not wish to receive our Helping Hands for Butterflies………………….7 newsletter in the future, simply Munching Caterpillars in Scotland………..…..8 reply to this message with the Books for Sale………………………...………..9 word ’unsubscribe’ in the title - thank you. RIC Project Officer - Job Vacancy……………9 Coul Links Update……………………………..10 VC Moth Recorder required for Caithness….10 Contact Details: Butterfly Conservation Scotland t: 01786 447753 Balallan House e: [email protected] Allan Park w: www.butterfly-conservation.org/scotland Stirling FK8 2QG Dates for your Diary Scottish Recorders’ Gathering - Saturday, 14th March 2020 For everyone interested in recording butterflies and moths, our Scottish Recorders’ Gathering will be held at the Battleby Conference Centre, by Perth on Saturday, 14th March 2020. It is an opportunity to meet up with others, hear all the latest butterfly and moth news and gear up for the season to come! All welcome - more details will follow in the New Year! Highland Branch AGM - Saturday, 18th April 2020 Our Highlands & Island Branch will be holding their AGM on Saturday, 18th April in a new venue, Green Drive Hall, 36 Green Drive, Inverness, IV2 4EU. More details will follow on the website in due course. -

Fishing Permits Information

Fishing permit retailers in the National Park 1 River Fillan 7 Loch Daine Strathfillan Wigwams Angling Active, Stirling 01838 400251 01786 430400 www.anglingactive.co.uk 2 Loch Dochart James Bayne, Callander Portnellan Lodges 01877 330218 01838 300284 www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk www.portnellan.com Loch Dochart Estate 8 Loch Voil 01838 300315 Angling Active, Stirling www.lochdochart.co. uk 01786 430400 www.anglingactive.co.uk 3 Loch lubhair James Bayne, Callander Auchlyne & Suie Estate 01877 330218 01567 820487 Strathyre Village Shop www.auchlyne.co.uk 01877 384275 Loch Dochart Estate Angling Active, Stirling 01838 300315 01786 430400 www.lochdochart.co. uk www.anglingactive.co.uk News First, Killin 01567 820362 9 River Balvaig www.auchlyne.co.uk James Bayne, Callander Auchlyne & Suie Estate 01877 330218 01567 820487 www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk www.auchlyne.co.uk Forestry Commission, Aberfoyle 4 River Dochart 01877 382383 Aberfoyle Post Office Glen Dochart Caravan Park 01877 382231 01567 820637 Loch Dochart Estate 10 Loch Lubnaig 01838 300315 Forestry Commission, Aberfoyle www.lochdochart.co. uk 01877 382383 Suie Lodge Hotel Strathyre Village Shop 01567 820040 01877 384275 5 River Lochay 11 River Leny News First, Killin James Bayne, Callander 01567 820362 01877 330218 Drummond Estates www.fishinginthetrossachs.co.uk 01567 830400 Stirling Council Fisheries www.drummondtroutfarm.co.uk 01786 442932 6 Loch Earn 12 River Teith Lochearnhead Village Store Angling Active, Stirling 01567 830214 01786 430400 St.Fillans Village Store www.anglingactive.co.uk -

Archaeological Excavations at Castle Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, (1996)6 12 , 517-557 Archaeological excavation t Castlsa e Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90 Gordon Ewart Triscottn Jo *& t with contributions by N M McQ Holmes, D Caldwell, H Stewart, F McCormick, T Holden & C Mills ABSTRACT Excavations Castleat Sween, Argyllin Bute,& have thrown castle of the history use lightthe on and from construction,s it presente 7200c th o t , day. forge A kilnsd evidencee an ar of industrial activity prior 1650.to Evidence rangesfor of buildings within courtyardthe amplifies previous descriptions castle. ofthe excavations The were funded Historicby Scotland (formerly SDD-HBM) alsowho supplied granta towards publicationthe costs. INTRODUCTION Castle Sween, a ruin in the care of Historic Scotland, stands on a low hill overlooking an inlet, Loch Sween, on the west side of Knapdale (NGR: NR 712 788, illus 1-3). Its history and architectural development have recently been reviewed thoroughl RCAHMe th y b y S (1992, 245-59) castle Th . e s theri e demonstrate havo dt e five major building phases datin c 1200 o earle gt th , y 13th century, c 1300 15te th ,h century 16th-17te th d an , h centur core y (illueTh . wor 120c 3) s f ko 0 consista f so small quadrilateral enclosure castle. A rectangular wing was added to its west face in the early 13th century. This win s rebuilgwa t abou t circulaa 1300 d an , r tower with latrinee grounth n o sd floor north-ease th o buils t n wa o t t enclosurcornee th 15te f o rth hn i ecentury l thesAl . -

Loch Lomond Loch Katrine and the Trossachs

Bu cxw 81 SON m m 0 OldBad on o 5 ey, L d n 1 S n/ r 7 ta mm St eet, Glea m Bu cxm 8c SON (INDIA) Lm rm War wzck Hom e For t Str eet Bom , . bay Bu cms a; SON (Gamma) m an Tor onto Pr oud bxGr eat Br itom by BlacM 8 8 0m h d., Gla:gow LIST OF I LLUSTRATIONS Fr ontzspzece Inch Cailleach Loch Lomond from Inver snaid nd o A hr a o ac Ben Venue a L ch c y, Tr ss hs d Pass o ac The Ol , Tr ss hs ’ Isl oc Katr ine Ellen s e, L h Glen Finglas or Finlas V IEW FROM BALLOCH BRI DGE Among the first of the featur es of Scotland which visitors to the country express a wish to see are the ” “ u n island reaches of the ! ee of Scottish Lakes , and the bosky narrows and mountain pass at the eastern r s . end of Loch Katrine, which ar e known as the T os achs 1 — During the Great War of 914 8, when large numbers of convalescent soldiers from the dominions overseas streamed through Glasgow, so great was their demand to see these famous regions, that constant parties had to be organized to conduct them over the ground. The interest of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs to the tourist of to-day is no doubt mostly due to the works 6 N LOCH LOMON D, LOCH KATRI E ’ of Sir Walter Scott . Much of the charm of Ellen s Isle and Inversnaid and the Pass of Balmaha would certainly vanish if Rob Roy and The Lady of the Lak e could be erased from our literature. -

Inchmahome Priory Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC073 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90169); Gardens and Designed Landscapes (GDL00218) Taken into State care: 1926 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2012 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE INCHMAHOME PRIORY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH INCHMAHOME PRIORY SYNOPSIS Inchmahome Priory nestles on the tree-clad island of Inchmahome, in the Lake of Menteith. It was founded by Walter Comyn, 4th Earl of Menteith, c.1238, though there was already a religious presence on the island. -

Supporting Rural Communities in West Dunbartonshire, Stirling and Clackmannanshire

Supporting Rural Communities in West Dunbartonshire, Stirling and Clackmannanshire A Rural Development Strategy for the Forth Valley and Lomond LEADER area 2015-2020 Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Area covered by FVL 8 3. Summary of the economies of the FVL area 31 4. Strategic context for the FVL LDS 34 5. Strategic Review of 2007-2013 42 6. SWOT 44 7. Link to SOAs and CPPs 49 8. Strategic Objectives 53 9. Co-operation 60 10. Community & Stakeholder Engagement 65 11. Coherence with other sources of funding 70 Appendix 1: List of datazones Appendix 2: Community owned and managed assets Appendix 3: Relevant Strategies and Research Appendix 4: List of Community Action Plans Appendix 5: Forecasting strategic projects of the communities in Loch Lomond & the Trosachs National Park Appendix 6: Key findings from mid-term review of FVL LEADER (2007-2013) Programme Appendix 7: LLTNPA Strategic Themes/Priorities Refer also to ‘Celebrating 100 Projects’ FVL LEADER 2007-2013 Brochure . 2 1. Introduction The Forth Valley and Lomond LEADER area encompasses the rural areas of Stirling, Clackmannanshire and West Dunbartonshire. The area crosses three local authority areas, two Scottish Enterprise regions, two Forestry Commission areas, two Rural Payments and Inspections Divisions, one National Park and one VisitScotland Region. An area criss-crossed with administrative boundaries, the geography crosses these boundaries, with the area stretching from the spectacular Highland mountain scenery around Crianlarich and Tyndrum, across the Highland boundary fault line, with its forests and lochs, down to the more rolling hills of the Ochils, Campsies and the Kilpatrick Hills until it meets the fringes of the urbanised central belt of Clydebank, Stirling and Alloa. -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

Kippen General Register of Poor 1845-1868 (PR/KN/5/1)

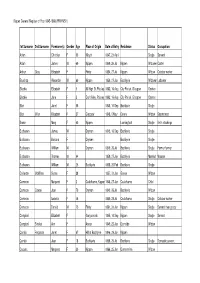

Kippen General Register of Poor 1845-1868 (PR/KN/5/1) 1st Surname 2nd Surname Forename(s) Gender Age Place of Origin Date of Entry Residence Status Occupation Adam Christian F 60 Kilsyth 1847, 21 April Single Servant Adam James M 69 Kippen 1849, 26 Jul Kippen Widower Carter Arthur Gray Elizabeth F Fintry 1854, 27 Jul Kippen Widow Outdoor worker Bauchop Alexander M 69 Kippen 1859, 27 Jan Buchlyvie Widower Labourer Blackie Elizabeth F 5 83 High St, Paisley 1862, 16 Aug City Parish, Glasgow Orphan Blackie Jane F 3 Croft Alley, Paisley 1862, 16 Aug City Parish, Glasgow Orphan Blair Janet F 65 1845, 16 Sep Buchlyvie Single Blair Miller Elizabeth F 37 Glasgow 1848, 6 May Denny Widow Seamstress Brown Mary F 60 Kippen Loaningfoot Single Knits stockings Buchanan James M Drymen 1845, 16 Sep Buchlyvie Single Buchanan Barbara F Drymen Buchlyvie Single Buchanan William M Drymen 1849, 26 Jul Buchlyvie Single Former farmer Buchanan Thomas M 64 1859, 27 Jan Buchlyvie Married Weaver Buchanan William M 25 Buchlyvie 1868, 20 Feb Buchlyvie Single Callander McMillan Susan F 28 1857, 31 Jan Govan Widow Cameron Margaret F 2 Cauldhame, Kippen 1848, 27 Jan Cauldhame Child Cameron Cowan Jean F 79 Drymen 1849, 26 Jul Buchlyvie Widow Cameron Isabella F 46 1859, 28 Jul Cauldhame Single Outdoor worker Cameron Donald M 75 Fintry 1861, 31 Jan Kippen Single Servant then grocer Campbell Elizabeth F Gargunnock 1845, 16 Sep Kippen Single Servant Campbell Sinclair Ann F Annan 1849, 25 Jan Darnside Widow Carrick Ferguson Janet F 67 Hill of Buchlyvie 1846, 29 Jan Kippen Carrick -

Duncan Mcneil's Presentation on the Village of Gargunnock Drawn From

Duncan McNeil’s Presentation on the Village of Gargunnock drawn from the old Statistical Accounts of 1796 & 1841 From the local history collection of John McLaren [email protected] Web Site www.gargunnockvillagehistory.co.uk Duncan McNeil’s Presentation on Gargunnock drawn from the old Statistical Accounts of 1796 & 1841 Mr McNeil’s handwritten presentation, delivered in the church hall in 1947, is held in the Stirling Council Archives at Borrowmeadow Road. It runs to 74 pages and contains an instruction at the end of line 3 on page 49 to go to an additional page 50 on which there are two paragraphs, one on the village and the other on the Rev John Stark with the further instruction to then return to the first page 50. Doing so would have resulted in the additional paragraphs being so obviously out of context that I have instead placed them in locations where they sit more comfortably within the surrounding text. They are printed in red. The photo above is of Duncan McNeil in the early 1950s. Duncan’s father Dugald worked all his life for the Stirlings of Gargunnock and Duncan, in turn, served in the same way. He and his wife lived in Shrub Cottage, Manse Brae but after his retirement moved to Hillview, Main St., Gargunnock. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ The matter which has gone to make up this presentation tonight has been taken almost entirely from two old Statistical Accounts of the parish of Gargunnock, which I have been fortunate enough to come across some years ago. These accounts were compiled by the Parish Ministers of that time, one in 1796 almost 152 years ago by the Rev.