Jerusalem Syndrome, Which Can Be Triggered by a Visit to the City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile

Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Jerusalem Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Jerusalem Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, village, and town in the Jerusalem Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all villages in Jerusalem Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in the Jerusalem Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Jerusalem Governorate. -

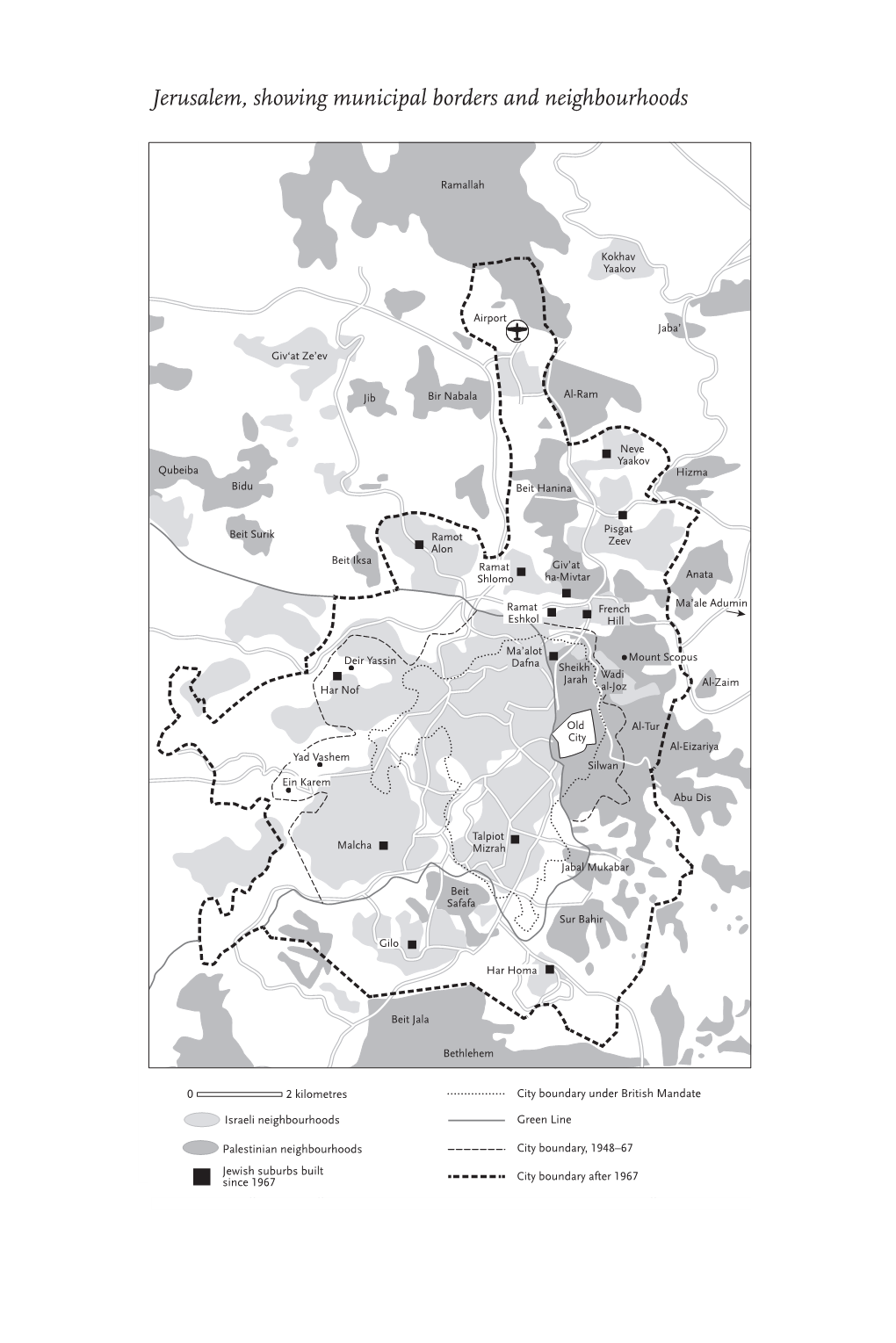

The Space of Contested Jerusalem the Middle East, Has Been a City of Quarters

The Space of Jerusalem is regarded as one of the classic divided cities,1 contested by two peoples, Contested separated by ethnicity, nationality, language Jerusalem and religion, with concrete and visible fissures embedded in the urban fabric. The Wendy Pullan terminology is widely used, by the Conflict in Cities research team as much as anyone else; nonetheless, the complexity of a city like Jerusalem increasingly calls to question the term ‘divided’, with its implied sense of clearly separated sections or two halves roughly equal to each other.2 With respect to Jerusalem, what do we really mean by divided? And if it is a divided city, what form does this take today, for clearly Jerusalem is not the same city that it was in 1967. Over forty years of occupation have produced a situation where the Israelis and Palestinians do not have equal rights and opportunities, and confusion and shifting policies underlie the way the Entrance to the tunnel under the Hebrew city has changed over time. This murky University, Mount Scopus. Source: Conflict in situation is particularly evident, although not Cities. always made explicit or addressed, in the Jerusalem Quarterly 39 [ 39 ] Map of Metropolitan Jerusalem showing settlements, villages and separation barrier. Source: Conflict in Cities. spatial qualities that characterise and differentiate the Palestinian and Israeli sectors. Significant historical residues are still in play in Jerusalem today, yet, much of what is understood as the city’s current urban space has been shaped by the conflict, and conversely, also impacts upon it. It would be fair to say that today the spaces which Israelis and Palestinians inhabit in Jerusalem are radically different from each other, although the divisions between them are not always simple or obvious. -

Science in Archaeology: a Review Author(S): Patrick E

Science in Archaeology: A Review Author(s): Patrick E. McGovern, Thomas L. Sever, J. Wilson Myers, Eleanor Emlen Myers, Bruce Bevan, Naomi F. Miller, S. Bottema, Hitomi Hongo, Richard H. Meadow, Peter Ian Kuniholm, S. G. E. Bowman, M. N. Leese, R. E. M. Hedges, Frederick R. Matson, Ian C. Freestone, Sarah J. Vaughan, Julian Henderson, Pamela B. Vandiver, Charles S. Tumosa, Curt W. Beck, Patricia Smith, A. M. Child, A. M. Pollard, Ingolf Thuesen, Catherine Sease Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 99, No. 1 (Jan., 1995), pp. 79-142 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/506880 Accessed: 16/07/2009 14:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aia. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. -

Jerusalem Between Segregation and Integration: Reading Urban Space Through the Eyes of Justice Gad Frumkin

chapter 8 Jerusalem between Segregation and Integration: Reading Urban Space through the Eyes of Justice Gad Frumkin Y. Wallach Introduction Jerusalem is seen as an archetypal example of a divided city, where extreme ethno-national polarization is deep rooted in a long history of segregation. In this chapter I challenge this perception by re-examining urban dynamics of late Ottoman and British Mandate Jerusalem, while questioning the manner in which urban segregation is theorized and understood. In the past few decades, there has been a reinvigorated scholarly discus- sion of urban segregation, driven by the challenges of difference and diversity.1 Entrenched segregation between different groups (defined by race, ethnicity, religion or class), or the “parallel lives” of different communities, living side by side with little contact, are seen to undermine the multicultural model of the late twentieth century. At the same time, mechanistic models of integration through urban mixing are increasingly challenged, and it is no longer accepted as evident that segregation is always undesirable. Nor is it obvious that everyday contact between different communities necessarily helps to engender greater understanding and dialogue. Scholars have been debating how to locate the discussion of urban encounter and segregation in the lived experience of the city. Writing on this topic suffers from the idealization of urban cosmopoli- tanism, on the one hand, or, conversely, describing segregation in overdeter- mined terms. To avoid this double pitfall, closer attention to the historical and spatial context is necessary, as well as close examination of socioeconomic real- ities. One suggestion, that I follow in this chapter, is to focus on life histories.2 By 1 This chapter forms part of ‘Conflict in Cities and the Contested Stated’ project, funded by the esrc’s Large Grants Programme (res-060-25-0015). -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

The New Israeli Land Reform August 2009

Adalah’s Newsletter, Volume 63, August 2009 The New Israeli Land Reform August 2009 Background On 3 August 2009, the Knesset (Israeli parliament) passed the Israel Land Administration (ILA) Law (hereinafter the “Land Reform Law”), with 61 Members of Knesset (MKs) voting in favor of the law and 45 MKs voting against it. The new land reform law is wide ranging in scope: it institutes broad land privatization; permits land exchanges between the State and the Jewish National Fund (Keren Kayemet Le-Israel) (hereinafter - the “JNF”), the land of which is exclusively reserved for the Jewish people; allows lands to be allocated in accordance with "admissions committee" mechanisms and only to candidates approved by Zionist institutions working solely on behalf of the Jewish people; and grants decisive weight to JNF representatives in a new Land Authority Council, which would replace the Israel Land Administration (ILA). The land privatization aspects of the new law also affect extremely prejudicially properties confiscated by the state from Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel; Palestinian refugee property classified as “absentee” property; and properties in the occupied Golan Heights and in East Jerusalem. Land Privatization Policy The law stipulates that 800,000 dunams of land currently under state-control will be privatized, enabling private individuals to acquire ownership rights in them. The reform will lead to the transfer of ownership in leased properties and land governed by outline plans enabling the issuance of building permits throughout the State of Israel in the urban, rural and agricultural sectors. Change in the organizational structure of the Israel Lands Administration The reform further stipulates a broad organizational re-structuring of the ILA. -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city. -

An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 5 Article 2 2000 Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Imseis, Ardi. "Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem." American University International Law Review 15, no. 5 (2000): 1039-1069. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACTS ON THE GROUND: AN EXAMINATION OF ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ARDI IMSEIS* INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1040 I. BACKGROUND ........................................... 1043 A. ISRAELI LAW, INTERNATIONAL LAW AND EAST JERUSALEM SINCE 1967 ................................. 1043 B. ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ......... 1047 II. FACTS ON THE GROUND: ISRAELI MUNICIPAL ACTIVITY IN EAST JERUSALEM ........................ 1049 A. EXPROPRIATION OF PALESTINIAN LAND .................. 1050 B. THE IMPOSITION OF JEWISH SETTLEMENTS ............... 1052 C. ZONING PALESTINIAN LANDS AS "GREEN AREAS"..... -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

Nickolay Mladenov Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process Security Council Briefing on the Situation in the Mi

(As Delivered) NICKOLAY MLADENOV SPECIAL COORDINATOR FOR THE MIDDLE EAST PEACE PROCESS SECURITY COUNCIL BRIEFING ON THE SITUATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST REPORT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF UNSCR 2334 (2016) 29 September 2020 Mister President, Members of the Security Council, On behalf of the Secretary-General, I will devote this briefing to presenting his fourteenth report on the implementation of Security Council resolution 2334, covering the period from 5 June to 20 September of this year. Before presenting the report, I would like to note the recent agreements between Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. The Secretary-General welcomes these agreements, which suspended Israeli annexation plans over parts of the occupied West Bank. The Secretary-General hopes that these developments will encourage Palestinian and Israeli leaders to re-engage in meaningful negotiations toward a two-State solution and will create opportunities for regional cooperation. He reiterates that only a two-State solution that realizes the legitimate national aspirations of Palestinians and Israelis can lead to sustainable peace between the two peoples and contribute to broader peace in the region. I am similarly encouraged by the call to restore hope in the peace process and resume negotiations on the basis of international law and agreed parameters, as made by the Foreign Ministers of Jordan, Egypt, France and Germany in Amman. The recent moves toward strengthening Palestinian unity as demonstrated by the outcome of the Fatah-Hamas meetings calling for long-awaited national presidential and legislative elections are also encouraging. Elections and legitimate democratic institutions are critical to uniting Gaza and the West Bank under a single national authority vital to upholding the prospect of a negotiated two-State solution.