Capitalism and Schizophrenia in Gotham City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USG Elects Jorgensen, Dimcevski As Senators Creates New Concerns (P

VOLUME 112 • ISSUE 11 BARUCH COLLEGE’S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER DECEMBER 4, 2017 OPINIONS 5 Water contamination USG elects Jorgensen, Dimcevski as senators creates new concerns (p. 5) Chemical companies that prioritize prof- its over people are introducing toxicity into public water supplies. Cor- porations like those that in- troduced lead into Flint, Michigan, need to be tightly regulated to prevent more dangerous incidents. BUSINESS 7 FCC chairman plans to revoke net neutrality (p. 7) FCC Chairman Ajit Pai has an- nounced his aim to revoke net neutrality NICOLE PUNG | THE TICKER regulations. If these rules are Jorgensen, left, and Dimcevski, right, join the table at the end of the Fall semester, and will continue to stay on as senators until the end of the Spring semester. repealed, the internet could BY BIANCA MONTEIRO be throttled by NEWS ASSISTANT internet service providers. Baruch College’s Undergraduate Student Government offi cially elected two new representative senators — Alexander Dimcevski and Emma Jor- gensen — on Nov. 21 during its senate meeting. A total of 14 students ran for the positions. Jorgensen was also confi rmed as chair of appeals, a position ARTS & STYLE 10 she took over after serving as interim chair for two weeks. Th e vacancy opened when former Treasurer Ehtasham Bhatti resigned and former Chair of DC superheroes unite in Appeals Suzanna Egan took his place on Nov. 9. Th e second vacancy followed the resignation of former Representative Sen. Josue Mendez. Th e two Justice League (p. 11) senators offi cially began serving on the table in the following senate meeting on Nov. -

Gotham Knights

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 11-1-2013 House of Cards Matthew R. Lieber University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Lieber, Matthew R., "House of Cards" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 367. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/367 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. House of Cards ____________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver ____________________________ In Partial Requirement of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ By Matthew R. Lieber November 2013 Advisor: Sheila Schroeder ©Copyright by Matthew R. Lieber 2013 All Rights Reserved Author: Matthew R. Lieber Title: House of Cards Advisor: Sheila Schroeder Degree Date: November 2013 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to approach adapting a comic book into a film in a unique way. With so many comic-to-film adaptations following the trends of action movies, my goal was to adapt the popular comic book, Batman, into a screenplay that is not an action film. The screenplay, House of Cards, follows the original character of Miranda Greene as she attempts to understand insanity in Gotham’s most famous criminal, the Joker. The research for this project includes a detailed look at the comic book’s publication history, as well as previous film adaptations of Batman, and Batman in other relevant media. -

The BG News January 20, 1989

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 1-20-1989 The BG News January 20, 1989 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News January 20, 1989" (1989). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4887. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4887 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Entertainment/Dining Guide in Friday Magazine THE BG NEWS Vol. 71 Issue 69 Bowling Green, Ohio Friday, January 20,1989 Bush reflects Reagan image by Scott R Whltehead and mor, R-Fifth District, Ohio, said "He has talked openly about improving education, Gillmor Elizabeth Kimes over the past eight years, Rea- some of the issues, such as edu- said there is much work to be gan strengthened the image and cation and the environment, but done. economy of the United States. Bush will not have to pursue the "Education is still going to "I think Reagan will be per- kind of increase in defense that remain state and local responsi- Gillmor Senate WASHINGTON — As the Rea- ceived as one of the better presi- Reagan had to when he took of- bility as 93 or 94 percent of the gan era comes to a close, all dents," Gillmor said. -

Duplicity: Exploring the Many Faces of Gotham

Duplicity: Exploring the many faces of Gotham “And man shall be just that for the overman: a laughing stock or a painful embarrassment.” - Friedrich Nietzsche, Also Sprach Zarathustra The Dark Knight, Christopher Nolan’s follow up to 2005’s convention- busting Batman Begins, has just broken the earlier box office record set by Spiderman 3 with a massive opening weekend haul of $158 million. While the figures say much about this franchise’s impact on the popular imagination, critical reception has also been in a rare instance overwhelmingly concurrent. What is even more telling is that the old and new opening records were both set by superhero movies. Much has already been discussed in the media about the late Heath Ledger’s brave performance and how The Dark Knight is a gritty new template for all future comic-to-movie adaptations, so we won’t go into much more of that here. Instead, let’s take a hard and fast look at absolutes and motives: old, new, black, white and a few in between. The brutality of The Dark Knight is also the brutality of America post-9/11: the inevitable conflict of idealism and reality, a frustrating political comedy of errors, and a rueful Wodehouseian reconciliation of the improbable with the impossible. Even as the film’s convoluted and always engaging plot breaks down some preconceptions about the psychology of the powerful, others are renewed (at times without logical basis) – that politicians are corruptible, that heroes are intrinsically flawed, that what you cannot readily comprehend is evil incarnate – and it isn’t always clear if this is an attempt at subtle irony or a weary concession to formula. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Activity Kit Proudly Presented By

ACTIVITY KIT PROUDLY PRESENTED BY: #BatmanDay dccomics.com/batmanday #Batman80 Entertainment Inc. (s19) Inc. Entertainment WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Bros. Warner © & TM SHIELD: WB and elements © & TM DC Comics. DC TM & © elements and WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters characters related all and BATMAN Copyright © 2019 DC Comics Comics DC 2019 © Copyright ANSWERS 1. ALFRED PENNYWORTH 2. JAMES GORDON 3. HARVEY DENT 4. BARBARA GORDON 5. KILLER CROC 5. LRELKI CRCO LRELKI 5. 4. ARARBAB DRONGO ARARBAB 4. 3. VHYRAE TEND VHYRAE 3. 2. SEAJM GODORN SEAJM 2. 1. DELFRA ROTPYHNWNE DELFRA 1. WORD SCRAMBLE WORD BATMAN TRIVIA 1. WHO IS BEHIND THE MASK OF THE DARK KNIGHT? 2. WHICH CITY DOES BATMAN PROTECT? 3. WHO IS BATMAN'S SIDEKICK? 4. HARLEEN QUINZEL IS THE REAL NAME OF WHICH VILLAIN? 5. WHAT IS THE NAME OF BATMAN'S FAMOUS, MULTI-PURPOSE VEHICLE? 6. WHAT IS CATWOMAN'S REAL NAME? 7. WHEN JIM GORDON NEEDS TO GET IN TOUCH WITH BATMAN, WHAT DOES HE LIGHT? 9. MR. FREEZE MR. 9. 8. THOMAS AND MARTHA WAYNE MARTHA AND THOMAS 8. 8. WHAT ARE THE NAMES OF BATMAN'S PARENTS? BAT-SIGNAL THE 7. 6. SELINA KYLE SELINA 6. 5. BATMOBILE 5. 4. HARLEY QUINN HARLEY 4. 3. ROBIN 3. 9. WHICH BATMAN VILLAIN USES ICE TO FREEZE HIS ENEMIES? CITY GOTHAM 2. 1. BRUCE WAYNE BRUCE 1. ANSWERS Copyright © 2019 DC Comics WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters and elements © & TM DC Comics. WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (s19) WORD SEARCH ALFRED BANE BATMOBILE JOKER ROBIN ARKHAM BATMAN CATWOMAN RIDDLER SCARECROW I B W F P -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Huntress Kindle

HUNTRESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Malinda Lo | 384 pages | 05 May 2011 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781907411090 | English | London, United Kingdom Huntress PDF Book In Lego Batman 2: DC Super Heroes , Huntress is an unlockable character in free play mode and can be found by constructing a Gold Brick archway after collecting the requisite number of gold bricks on the roof of a building in the south east of the top island on the map, south east of the encounter with Ra's al Ghul. In this iteration of the character, she was kidnapped as a child aged 6 and raped by a rival mafia don purely to psychologically torture her father and is a withdrawn girl. After she witnesses the mob-ordered murder of her parents at the age of 19, she crusades to put an end to the Mafia. Arkham Knight. Bruce Wayne. She helps him to take down the enemies including Lyle Bolton and back Felicity. Fictional character. Gardner Fox. Dinah Drake Dinah Laurel Lance. Jones V-Man Wonder Man. During the League's restructuring following the Rock of Ages crisis, Batman sponsors Huntress' membership in the Justice League , [6] hoping that the influence of other heroes will mellow the Huntress, and for some time, Huntress is a respected member of the League. Members Only Merchandise Grow your collection with a wide range of exclusive merchandise—including the all-new Justice League Animated Series action figures —available in our members only store. Batgirl and the Birds of Prey. The stadiums may be empty, but believe it or not, the MLB playoffs have arrived. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

For Immediate Release Second Night of 2017 Creative Arts

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SECOND NIGHT OF 2017 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® WINNERS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. – September 10, 2017) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of its two 2017 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Ceremonies honoring outstanding artistic and technical achievement in television at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles. The ceremony honored performers, artists and craftspeople for excellence in scripted programming including comedy, drama and limited series. Executive produced by Bob Bain, the Creative Arts Emmy Awards featured presenters from the season’s most popular show including Hank Azaria (Brockmire and Ray Donovan), Angela Bassett (911 and Black Panther), Alexis Bledel (The Handmaid’s Tale), Laverne Cox (Orange Is the New Black), Joseph Gordon-Levitt (Are You There Democracy? It's Me, The Internet) and Tom Hanks (Saturday Night Live). Press Contacts: Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight (for the Television Academy) [email protected], (818) 462-1150 Laura Puig breakwhitelight (for the Television Academy) [email protected], (956) 235-8723 For more information please visit emmys.com. TELEVISION ACADEMY 2017 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent accounting firm of Ernst & Young LLP, were distributed as follows: Program Individual Total HBO 3 16 19 Netflix 1 15 16 NBC - 9 9 ABC 2 5 7 FOX 1 4 5 Hulu - 5 5 Adult Swim - 4 4 CBS 2 2 4 FX Networks - 4 4 A&E 1 2 3 VH1 - 3 3 Amazon - 2 2 BBC America 1 1 2 ESPN - 2 2 National Geographic 1 1 2 AMC 1 - 1 Cartoon Network 1 - 1 CNN 1 - 1 Comedy Central 1 - 1 Disney XD - 1 1 Samsung / Oculus 1 - 1 Showtime - 1 1 TBS - 1 1 Viceland 1 - 1 Vimeo - 1 1 A complete list of all awards presented tonight is attached. -

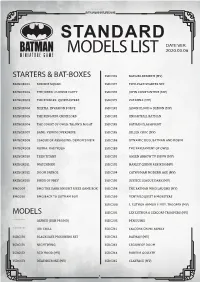

Batman Miniature Game Standard List

BATMANMINIATURE GAME STANDARD DATE VER. MODELS LIST 2020.03.06 35DC176 BATGIRL REBIRTH (MV) STARTERS & BAT-BOXES BATBOX001 SUICIDE SQUAD 35DC177 TWO-FACE STARTER SET BATBOX002 THE JOKER: CLOWNS PARTY 35DC178 JOHN CONSTANTINE (MV) BATBOX003 THE RIDDLER: QUIZMASTERS 35DC179 ZATANNA (MV) BATBOX004 MILITIA: INVASION FORCE 35DC181 JASON BLOOD & DEMON (MV) BATBOX005 THE PENGUIN: CRIMELORD 35DC182 KNIGHTFALL BATMAN BATBOX006 THE COURT OF OWLS: TALON’S NIGHT 35DC183 BATMAN FLASHPOINT BATBOX007 BANE: VENOM OVERDRIVE 35DC185 KILLER CROC (MV) BATBOX008 LEAGUE OF ASSASSINS: DEMON’S HEIR 35DC188 DYNAMIC DUO, BATMAN AND ROBIN BATBOX009 KOBRA: KALI YUGA 35DC189 THE PARLIAMENT OF OWLS BATBOX010 TEEN TITANS 35DC191 GREEN ARROW TV SHOW (MV) BATBOX011 WATCHMEN 35DC192 HARLEY QUINN REBIRTH (MV) BATBOX012 DOOM PATROL 35DC194 CATWOMAN MODERN AGE (MV) BATBOX013 BIRDS OF PREY 35DC195 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK (MV) BMG009 BMG THE DARK KNIGHT RISES GAME BOX 35DC198 THE BATMAN WHO LAUGHS (MV) BMG010 BMG BACK TO GOTHAM BOX 35DC199 VENTRILOQUIST & MOBSTERS 35DC200 L. LUTHOR ARMOR & HVY. TROOPER (MV) MODELS 35DC201 LEX LUTHOR & LEXCORP TROOPERS (MV) ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨ ALFRED (DKR PROMO) 35DC205 PENGUINS “““““““““ JOE CHILL 35DC211 FALCONE CRIME FAMILY 35DC170 BLACKGATE PRISONERS SET 35DC212 BATMAN (MV) 35DC171 NIGHTWING 35DC213 LEGION OF DOOM 35DC172 RED HOOD (MV) 35DC214 ROBIN & GOLIATH 35DC173 DEATHSTROKE (MV) 35DC215 CLAYFACE (MV) 1 BATMANMINIATURE GAME 35DC216 THE COURT OWLS CREW 35DC260 ROBIN (JASON TODD) 35DC217 OWLMAN (MV) 35DC262 BANE THE BAT 35DC218 JOHNNY QUICK (MV) 35DC263 -

The World Today Is a Dangerous Place, Filled

INTERVIEW THE WORLD TODAY IS A DANGEROUS PLACE, FILLED WITH VIOLENCE INTERVIEW WITH BRUCE SCIVALLY CONDUCTED BY MICHAł CHUDOLIńSKI 40 MICHAł CHUDOLIńSKI: WHAT ARE THE ORIGINS OF BATMAN’S B.S.:Bill Finger was a former shoe salesman B.S.: The huge success of the campy, comedic thought he would be able to land a movie PHYSICAL APPEARANCE? IT IS SAID THAT IN THE BEGINNING HE WAS whom artist Bob Kane took on as a partner 1966 ‑68 Batman TV show created an image deal immediately, but the studios couldn’t SUPPOSED TO WEAR A RED SUIT AND HAVE BLONDE HAIR... because Kane, though a passable artist, was in the public consciousness of Batman as see any commercial potential in producing Bruce Scivally: When Bob Kane first created not good at coming up with stories. Kane and a comedic character. Comic book enthusiast a movie based on a goofy 1960s TV series. Batman, his original idea was for a character Finger were collaborators on comic strips like Michael Uslan was obsessed with bringing Uslan kept fighting for his vision of Batman, in a red costume with a little black domino “Clip Carson” for National Comics before a version of Batman to the movies that would commissioning scripts and approaching mask, the kind that Robin eventually wore. they jointly created Batman. However, Kane be more like the very first Batman comics, or directors. It was only after he met with He went to his collaborator, Bill Finger, who was a much more savvy businessman than like the comic book stories of the 1970s, in superstar producers Peter Guber and Jon suggested that instead Batman should have Finger, and Kane had it put into his contract which Batman was a dark vigilante.