DM11 HMO Topic Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14Th May 2019

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14th May 2019 Subject: Houses in Multiple Occupation Article 4 Direction Report of: Director, Inclusive Growth Relevant Cabinet Councillor Ian Ward, Leader of the Council Members: Councillor Sharon Thompson, Cabinet Member for Homes and Neighbourhoods Councillor John Cotton, Cabinet Member for Social Inclusion, Community Safety and Equalities Relevant O &S Chair(s): Councillor Penny Holbrook, Housing & Neighbourhoods Report author: Uyen-Phan Han, Planning Policy Manager, Telephone No: 0121 303 2765 Email Address: [email protected] Are specific wards affected? ☒ Yes ☐ No If yes, name(s) of ward(s): All wards Is this a key decision? ☒ Yes ☐ No If relevant, add Forward Plan Reference: 006417/2019 Is the decision eligible for call-in? ☒ Yes ☐ No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? ☐ Yes ☒ No 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Cabinet approval is sought to authorise the making of a city-wide direction under Article 4 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015. This will remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 Use Class) to houses in multiple occupation (C4 Use Class) that can accommodate up to 6 people. 1.2 Cabinet approval is also sought to authorise the cancellation of the Selly Oak, Harborne and Edgbaston Article 4 Direction made under Article 4(1) of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 1995. This is to avoid duplication as the city-wide Article 4 Direction will cover these areas. Page 1 of 8 2 Recommendations 2.1 That Cabinet authorises the Director, Inclusive Growth to prepare a non- immediate Article 4 direction which will be applied to the City Council’s administrative area to remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 use) to small houses in multiple occupation (C4 use). -

The VLI Is a Composite Index Based on a Range Of

OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership URN Date Issued CSP-SA-02 v3 11/02/2019 Customer/Issued To: Head of Community Safety, Birmingham Birmi ngham Community Safety Partnership Strategic Assessment 2019 The profile is produced and owned by West Midlands Police, and shared with our partners under statutory provisions to effectively prevent crime and disorder. The document is protectively marked at OFFICIAL but can be subject of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 or Criminal Procedures and Investigations Act 1996. There should be no unauthorised disclosure of this document outside of an agreed readership without reference to the author or the Director of Intelligence for WMP. Crown copyright © and database rights (2019) Ordnance Survey West Midlands Police licence number 100022494 2019. Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Licence number 100017302. 1 Page OFFICIAL OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Contents Key Findings .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Reducing -

Accommodation Brochure

You've found the right place Everything you need to know about student accommodation Contents Welcome to your new home What's it like to live here? 3 Starting university means lots of exciting Your wellbeing 4 changes. New place, new people; perhaps living Inclusive living 5 independently for the first time. Sustainability 6 Give yourself the security of a safe place to live Meal Plan 7 that really feels like home. Campus map 8 – 9 Types of accommodation 10 The facts Villages 11 En-suite accommodation 12 – 14 91% 75% Shared accommodation 15 – 17 Studios and apartments 18 satisfied with their described accommodation accommodation as Choosing where to live 19 GOOD or VERY GOOD FAQ 20 – 21 How to apply 22 – 23 Fees 24 70% GOOD or of our VERY GOOD value accommodation for money is en-suite all accommodation accommodation within 1-mile radius had a positive of central campus impact on wellbeing What’s it like to live here? Having the best time of my life here! I love It's great. I am disabled and they've been really Birmingham as a city, our campus is beautiful, loving helpful. Campus is beautiful and also very accessible. my accommodation and flatmates and the course is My lecturers are so lovely and the people are great. extremely interesting as well! Feedback statistics in this brochure are taken from the independent National Student Housing Survey 2019/20. Testimonials were posted by current or recent students on Stunning campus, amazing community, love it. Studentcrowd.com, Studenthut.com and Hallbookers.co.uk. -

West Midlands Fire and Rescue Authority

WEST MIDLANDS FIRE AND RESCUE AUTHORITY Monday, 18 February 2019 at 11:00 FIRE SERVICE HEADQUARTERS, 99 VAUXHALL ROAD, BIRMINGHAM, B7 4HW Page 1 of 254 Distribution of Councillors Birmingham D Barrie Z Iqbal K Jenkins S Spence Coventry C Miks S Walsh Dudley A Aston N Barlow Sandwell J Edwards C Tranter Solihull P Hogarth Walsall S Craddock A Young Wolverhampton G Brackenridge J Dehar Police & Crime Commissioner D Jamieson Co-opted Members Professor S Brake S Middleton Car Parking will be available for Members at Fire Service Headquarters. Accommodation has been arranged from 10.00 am for meetings of the various Political Groups. Page 2 of 254 Fire Authority You are summoned to attend the meeting of Fire Authority to be held on Monday, 18 February 2019 at 11:00 at Fire Service HQ, 99 Vauxhall Road, Nechells, Birmingham B7 4HW for the purpose of transacting the following business: Agenda – Public Session 1 To receive apologies for absence (if any) 2 Chair’s announcements 3 Declarations of interests in contracts or other matters 4 Minutes of the Fire Authority held on 19 November 2018 7 - 16 5 Investment in Support Services 17 - 24 6 Strategy Option 2019-2020 25 - 32 7 Budget and Precept 2019-2020 33 - 88 8 Proposed Vehicle Replacement Programme 2019-20 to 2021-22 89 - 96 9 2019-2020 Property Asset Management Plan 97 - 116 10 The Plan 2019-2022 x1 117 - 128 11 Monitoring of Finances 129 - 134 12 Pay Policy Statement 2019-20.docx 135 - 186 Page 3 of 254 13 Arrangements to Act in Matters of Emergency - Laying of the 187 - Statutory Order for -

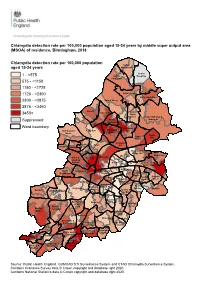

MSOA) of Residence, Birmingham, 2018

Chlamydia detection rate per 100,000 population aged 15-24 years by middle super output area (MSOA) of residence, Birmingham, 2018 Chlamydia detection rate per 100,000 population Sutton aged 15-24 years Mere Green Sutton 1 - <575 Sutton Roughley Four Oaks 575 - <1150 1150 - <1725 1725 - <2300 Sutton Trinity Sutton Reddicap 2300 - <2875 Sutton Vesey 2875 - <3450 Oscott Kingstanding Sutton 3450+ Wylde Green Sutton Walmley & Perry Minworth Suppressed Common Ward boundary Erdington Handsworth Perry Barr Stockland Wood Green Castle Pype Vale Hayes Gravelly Birchfield Aston Hill Holyhead Handsworth Lozells Bromford & Hodge Hill Ward End Shard End Soho & Newtown Nechells Jewellery Quarter Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Heartlands North Ladywood Bordesley & Edgbaston Highgate Yardley East Garretts Bordesley Yardley Green Green Small West & Heath Stechford Sparkbrook & South Balsall Balsall Heath Edgbaston Yardley Sheldon Heath East Tyseley & Quinton Harborne West Hay Mills Sparkhill Bournbrook Moseley & Selly Acocks Weoley & Park Green Bartley Selly Oak Green Hall Green North Stirchley Billesley Bournville & Cotteridge Brandwood & Hall Green King's Heath South Allens Cross Druids Heath Highter's King's Norton & Monyhull Heath North Frankley Northfield Great Park King's Longbridge & Norton Rubery & West Heath South Rednal Source: Public Health England, GUMCAD STI Surveillance System and CTAD Chlamydia Surveillance System. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2020. Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright -

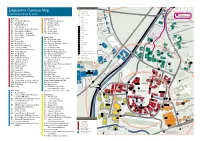

Edgbaston Campus Map (PDF)

Key utes min 15 G21 Edgbaston Campus Map Y2 Building name Information point Oakley Court SOMER SET ROAD Index to buildings by zone Level access entrance The Vale Footpath Steps Medical Practice B9 The Elms and Dental Centre Day Nursery Red Zone Orange Zone P Visitors car park Tennis Court R0 The Harding Building O1 The Guild of Students H Hospital D G20 A R1 Law Building O2 St Francis Hall 24 24 hour security O Pritchatts House R Bus stops RD R2 Frankland Building O3 University House A Athletics Track HO R G19 Library Ashcroft U R3 Hills Building O4 Ash House RQ Park House AR Museum HA R4 Aston Webb – Lapworth Museum O5 Beech House F L U A Pritchatts Park N Q A Sport facilities C Village R R5 Aston Webb – B Block P M O6 Cedar House A R A H F G I First aid T IN M R6 Aston Webb – Great Hall C R O7 Sport & Fitness E 13 Pritchatts Road I B GX H D D Food and drink The Spinney A N Environmental G18 Priorsfield A G R7 Aston Webb – Student Hub T R T E Research Facility B T S Retail ES A C R8 Physics West Green Zone R R S O T Toilets O W A O R9 Nuffield G1 32 Pritchatts Road N D G5 Lucas House Hotel ATM P G16 Pritchatts Road P R10 Physics East G2 31 Pritchatts Road A Car Park R Canal bridge K Conference R11 Medical Physics G3 European Research Institute R Park s G14 O Sculpture trail inute R12 Bramall Music Building G4 3 Elms Road B8 10 m Garth House A G4 D R13 Poynting Building G5 Computer Centre Rail G15 Westmere R14 Barber Institute of Fine Arts Lift G6 Metallurgy and Materials D B6 A Electric Vehicle Charge Point B7 Edgbaston R15 Watson Building -

Ward Meetings and Ward Plans Update

Date updated: 23.02.2021 Ward Meetings and Ward Plans Update 1. Ward Forum Meetings 1.1 Number of Virtual Meetings and Attendance (April 2020-March 2021) *Meeting arranged but not yet taken place **The NDSU YouTube Channel was set up in November 2020 (Q3) Year Meetings Total Average Number of Total Average (2020- that were YouTube YouTube Meetings Attendance Attendance 2021) joint Views** Views Q1 (Apr- 7 230 33 145 21 Jun) Q2 (Jul- 23 1 587 27 235 11 Sep) Q3 (Oct- 31 6 723 23 811 29 Dec) Q4 (Jan- 21 & 20* 1 & 4* 601 29 977 75 Mar) Grand 102 12 2,141 26 2,168 31 Total (82 & 20*) (8 & 4*) 1.2 Total Number of Meetings by Ward *Meeting arranged but not yet taken place ***Meeting arranged but not completed (technology error) April 2020- May 2018-April May 2019- Ward March 2021 2019 March 2020 (Virtual) Acocks Green 4 5 2 & 1* Allens Cross 2 1 1 Alum Rock 3 0 2 & 1* Aston 2 2 1 Balsall Heath West 3 5 1 & 1* Bartley Green 3 3 0 Billesley 1 1 1* Birchfield 5 4 2 & 1* Bordesley & Highgate 1 0 2 Bordesley Green 1 0 1* Bournbrook & Selly Park 3 1 2 Bournville & Cotteridge 3 3 2 & 1* Brandwood & Kings Heath 3 2 0 Bromford & Hodge Hill 5 2 6 Date updated: 23.02.2021 April 2020- May 2018-April May 2019- Ward March 2021 2019 March 2020 (Virtual) Castle Vale 2 0 0 Druids Heath & Monyhull 5 3 2 & 1* Edgbaston 2 3 0 Erdington 3 1 1 Frankley Great Park 2 1 2 Garretts Green 2 0 1 Glebe Farm & Tile Cross 6 2 1 Gravelly Hill 3 3 1 & 1* Hall Green North 4 4 2 & 1* Hall Green South 2 1 0 Handsworth 4 3 3 Handsworth Wood 4 3 1* Harborne 4 2 2*** & 1 Heartlands -

NHS Birmingham and Solihull Clinical Commissioning Group Primary

NHS Birmingham and Solihull Clinical Commissioning Group Primary Care Networks April 2021 PCN Name ODS CODE Practice Name Name of Clinical GP Provider Alignment/ Director Federation Alliance of Sutton Practices M85033 The Manor Practice Dr Fraser Hewett Our Health Partnership PCN M85026 Ashfield Surgery M85175 The Hawthorns Surgery Balsall Heath, Sparkhill and M85766 Balsall Heath Health Centre – Dr Raghavan Dr Aman Mann SDS My Healthcare Moseley PCN M85128 Balsall Heath Health Centre – Dr Walji M85051 Firstcare Health Centre M85116 Fernley Medical Centre Y05826 The Hill General Practice M85713 Highgate Medical Centre M85174 St George's Surgery (Spark Medical Group) M85756 Springfield Medical Practice Birmingham East Central M85034 Omnia Practice Dr Peter Thebridge Independent PCN M85706 Druid Group M85061 Yardley Green Medical Centre M85113 Bucklands End Surgery M85013 Church Lane Surgery Bordesley East PCN Y02893 Iridium Medical Practice Dr Suleman Independent M85011 Swan Medical Practice M85008 Poolway Medical Centre M85694 Garretts Green M85770 The Sheldon Practice Bournville and Northfield M85047 Woodland Road Dr Barbara King Our Health Partnership PCN M85030 St Heliers M85071 Wychall Lane Surgery M85029 Granton Medical Centre NHS Birmingham and Solihull Clinical Commissioning Group Primary Care Networks April 2021 Caritas PCN M88006 Cape Hill Medical Centre Dr Murtaza Master Independent M88645 Hill Top Surgery (SWB CCG) M88647 Rood End Surgery (SWB CCG) Community Care Hall Green Y00159 Hall Green Health Dr Ajay Singal Independent -

63 Birmingham

63 Birmingham - Frankley via Northfield, Rubery Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Old Square (Stop BS8) 0101 0201 0406 0451 0531 0601 0626 0644 0657 0707 0717 0727 0737 0747 0757 0807 0817 0827 Cannon Hill Park, Priory Road (after) 0109 0209 0414 0500 0541 0611 0636 0654 0708 0718 0728 0739 0749 0759 0809 0819 0829 0839 Northfield, Bell Lane 0119 0219 0424 0511 0553 0623 0648 0708 0722 0732 0745 0756 0806 0816 0827 0837 0847 0857 Leach Green Lane 0127 0227 0432 0520 0602 0634 0659 0720 0734 0744 0757 0808 0818 0828 0839 0849 0859 0909 Arden Walk (opposite) 0441 0529 0612 0645 0711 0732 0747 0757 0810 0821 0831 0841 0852 0902 0912 0919 Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Old Square (Stop BS8) 0837 0847 0857 0908 0920 0932 0944 0956 1008 1020 1032 1044 1056 1108 1120 1132 1144 1156 Cannon Hill Park, Priory Road (after) 0849 0859 0909 0920 0932 0944 0956 1008 1020 1032 1044 1056 1108 1120 1132 1144 1156 1208 Northfield, Bell Lane 0907 0917 0927 0938 0950 1002 1014 1026 1038 1050 1102 1114 1126 1138 1150 1202 1214 1226 Leach Green Lane 0918 0928 0938 0949 1001 1013 1025 1037 1049 1101 1113 1125 1137 1149 1201 1213 1225 1237 Arden Walk (opposite) 0928 0938 0948 0959 1011 1023 1035 1047 1059 1111 1123 1135 1147 1159 1211 1223 1235 1247 Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Old Square (Stop BS8) 1208 1220 1232 1244 1256 1308 1320 1332 1344 1356 1408 1420 -

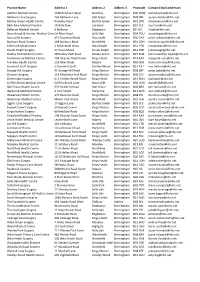

Practice Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Postcode Contact Email

Practice Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Postcode Contact Email Addresses Ashtree Medical Centre 1536 Pershore Road Stirchley Birmingham B30 2NW [email protected] Baldwins Lane Surgery 265 Baldwins Lane Hall Green Birmingham B28 0RF [email protected] Bartley Green Health Centre Romsley Road Bartley Green Birmingham B32 3PR [email protected] Bath Row Medical Practice 10 Bath Row Lee Bank Birmingham B15 1LZ [email protected] Bellevue Medical Centre 6 Bellevue Edgbaston Birmingham B5 7LX [email protected] Bournbrook & Varsity Medical Centre1A Alton Road Selly Oak Birmingham B29 7DU [email protected] Bournville Surgery 41b Sycamore Road Bournville Birmingham B30 2AA [email protected] Bunbury Road Surgery 108 Bunbury Road Northfield Birmingham B31 2DN [email protected] Cofton Medical Centre 2 Robinsfield Drive West Heath Birmingham B31 4TU [email protected] Druids Heath Surgery 27 Pound Road Druids Heath Birmingham B14 5SB [email protected] Dudley Park Medical Centre 28 Dudley Park Road Acocks Green Birmingham B27 6QR [email protected] Featherstone Medical Centre 158 Alcester Road South Kings Heath Birmingham B14 6AA [email protected] Frankley Health Centre 125 New Street Rubery Birmingham B45 0EU [email protected] Goodrest Croft Surgery 1 Goodrest Croft Yardley Wood Birmingham B14 4JU [email protected] Grange Hill Surgery 41 Grange Hill Road Kings Norton Birmingham B38 8RF [email protected] Granton Surgery 114 Middleton Hall Road Kings Norton Birmingham B30 1DJ [email protected] Greenridge -

Interconnect Improving the Journey Experience Interconnect: Improving the Journey Experience

Interconnect Improving the journey experience Interconnect: Improving the journey experience Piloted in the centre of Birmingham, UK, Interconnect Interconnect delivers a visionary blueprint seeks to improve the journey experience for people living for connecting the journey experience. in and visiting the West Midlands region. The project seeks to improve the quality of information across all media channels, transport services and public environments. Interconnect is a partnership, project In turn the approach is helping attract and innovative design approach focused visitors, tourism and investment that will on improving the ‘interface’ between support new jobs and a stronger economy, people, places and transport systems. building the reputation of the region The project promotes a vision of a internationally and contributing towards world class movement network with social, environmental and economic infrastructure and passenger facilities benefi ts for all. designed to create welcoming places In support of the vision, the Interconnect supported by legible and intuitive partnership is encouraging new ways information systems. of working, enabling organisations Piloted for the fi rst time in the West to plan, develop and deliver effective Midlands region of the United Kingdom, improvements to the journey experience. Interconnect aims to improve the journey The Interconnect partners are sharing experience for people, whether they are knowledge, identifying mutually benefi cial visiting for the fi rst time, or making their opportunities and maximising investment daily commute. – delivering major improvements for Investment in ongoing regeneration everyone who lives and works in, or and renewal projects is delivering radical visits the region. changes to the region. The benefi ts of This publication will be of value to other this investment are being maximised places, cities and regions who wish to by interconnecting transport, tourism, improve the journey experience. -

Bournbrook and We Hope That You Settle in Quickly and Enjoy Your Stay

WELCOME We are very pleased that you have chosen to live at Bournbrook and we hope that you settle in quickly and enjoy your stay. We have prepared this document which contains important safety and practical information and also to help you understand how your accommodation is managed and to help you get to know your residence. Please take the time to read through the contents of this document and if you have any queries please contact a member of staff. I know this is an exciting time for you coming to university to live and study independently but it may also be a little daunting for some. But don’t worry, if there is anything you are not sure about in relation to your accommodation and this document does not contain the answer please contact staff for help. For more general information about the University, registration, finance, accommodation and study support I would recommend that you go to the two links below, if you haven’t already, as there is information available which will be important throughout your time here. www.birmingham.ac.uk/welcome/index.aspx www.as.bham.ac.uk/support/ Our staff will be pleased to assist you with any queries or concerns you may have during your stay. A member of staff will be available to speak to 24 hours a day by phoning Selly Oak Village Reception from your mobile on 0121 415 1011 (1011 from the phone in your hallway). All staff wear uniforms and name badges and we should get to know each other quickly over the coming weeks.