Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4.35 B.A. /M.A. 5 Years Integrated Course in Pali A.Y. 2017-18

Cover Page AC___________ Item No. ______ UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Syllabus for Approval Sr. No. Heading Particulars Title of the B.A./M.A. Five Year Integrated Course In 1 Course Pali Eligibility for As per existing Ordinances & policy 2 Admission Passing As per University Credit Semester System 3 Marks 2017 Ordinances / 4 - Regulations ( if any) No. of Years / 5 5 Years Semesters P.G. / U.G./ Diploma / Certificate 6 Level ( Strike out which is not applicable) Yearly / Semester 7 Pattern ( Strike out which is not applicable) New / Revised 8 Status ( Strike out which is not applicable) To be implemented 9 From Academic Year 2017-2018 from Academic Year Date: Signature : Name of BOS Chairperson / Dean : ____________________________________ 1 Cover Page UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Essentials Elements of the Syllabus B.A./M.A. Five Year Integrated Course In 1 Title of the Course Pali 2 Course Code - Preamble / Scope:- The traditional way of learning Pali starts at an early age and gradually develops into ethically strong basis of life. Now at the university though we cannot give the monastic kind of training to the students, the need of the time is -a very strong foundation of sound mind and body, facing the stress and challenges of the life. There is necessity of Pali learning for a long time from early age which few schools in Maharashtra are giving, but not near Mumbai. Mumbai University has only one college which satisfies the need of Pali learning at the undergraduate and graduate level those too only three papers in Pali. The interest in the study of Pali language and literature is on the rise. -

Chronology of the Pali Canon Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D., M.A., B.L

Chronology of the Pali Canon Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D., M.A., B.L. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Researchnstitute, Poona, pp.171-201 Rhys Davids in his Buddhist India (p. 188) has given a chronological table of Buddhist literature from the time of the Buddha to the time of Asoka which is as follows:-- 1. The simple statements of Buddhist doctrine now found, in identical words, in paragraphs or verses recurring in all the books. 2. Episodes found, in identical words, in two or more of the existing books. 3. The Silas, the Parayana, the Octades, the Patimokkha. 4. The Digha, Majjhima, Anguttara, and Samyutta Nikayas. 5. The Sutta-Nipata, the Thera-and Theri-Gathas, the Udanas, and the Khuddaka Patha. 6. The Sutta Vibhanga, and Khandhkas. 7. The Jatakas and the Dhammapadas. 8. The Niddesa, the Itivuttakas and the Patisambbhida. 9. The Peta and Vimana-Vatthus, the Apadana, the Cariya-Pitaka, and the Buddha-Vamsa. 10. The Abhidhamma books; the last of which is the Katha-Vatthu, and the earliest probably the Puggala-Pannatti. This chronological table of early Buddhist; literature is too catechetical, too cut and dried, and too general to be accepted in spite of its suggestiveness as a sure guide to determination of the chronology of the Pali canonical texts. The Octades and the Patimokkha are mentioned by Rhys Davids as literary compilations representing the third stage in the order of chronology. The Pali title corresponding to his Octades is Atthakavagga, the Book of Eights. The Book of Eights, as we have it in the Mahaniddesa or in the fourth book of the Suttanipata, is composed of sixteen poetical discourses, only four of which, namely, (1.) Guhatthaka, (2) Dutthatthaka. -

A Anguttara Nikiiya D Digha Nikaya M Majjhima Nikaya S Samyutta Niklzya Dh Dhammapada It Itivuttaka Ud Udiina

Notes The following abbreviations occur in the Notes: A Anguttara Nikiiya D Digha Nikaya M Majjhima Nikaya S Samyutta Niklzya Dh Dhammapada It Itivuttaka Ud Udiina I BASIC FEATURES OF BUDDHIST PSYCHOLOGY I Robert H. Thouless, Riddel Memorial Lectures, (Oxford, 1940), p. 47. 2 Mrs C. A. F. Rhys Davids, Buddhist Psychology, (London, 1914). 3 Rune Johansson, The Psychology ofNirvana (London, 1965), P:II. 4 The material pertaining to the psychology ofBuddhism is basically drawn from the suttapitaka. 5. Carl R. Rogers, 'Some Thoughts Regarding The Current Philosophy of the Behavioural Sciences', Journal ofHumanistic Psychology, autumn 1965. 6 Stuart Hampshire (ed.), Philosophy ofMind (London, 1966) 7 Dh., 183. 8 M I, 224. 9 O. H. de A. Wijesekera, Buddhism and Society, (Sri Lanka, 1952), P: 12. 10 DIll, 289. II S V, 168. 12 Wijesekera, Ope cit., P: 12. 13 DIll, Sutta 26. 14 A II, 16. 15 The Sangiiraoa Sutta refers to three groups of thinkers: (I) Traditionalists (anussavikii) , (2) Rationalists and Metaphysicians (takki vzma'rlSl) , (3) Ex perientialists who had personal experience of a higher knowledge. 16 Nanananda, Concept and Reality (Sri Lanka, 1971), Preface. 17 For an analysis of the Buddhist theory of knowledge, see K. N.Jayatilleke, Early Buddhist Theory ofKnowledge (London, 1963). 18 See, K. N.Jayatilleke, 'The Buddhist Doctrine of Karma' (mimeo, 1948) p. 4; The analysis pertaining to the several realms within which the laws of the universe operate is found in the works of commentary, and not in the main discourses of the Buddha. 19 Far a comprehensive study of the Buddhist concept of causality see David J. -

The Oral Transmission of the Early Buddhist Literature

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 27 Number 1 2004 David SEYFORT RUEGG Aspects of the Investigation of the (earlier) Indian Mahayana....... 3 Giulio AGOSTINI Buddhist Sources on Feticide as Distinct from Homicide ............... 63 Alexander WYNNE The Oral Transmission of the Early Buddhist Literature ................ 97 Robert MAYER Pelliot tibétain 349: A Dunhuang Tibetan Text on rDo rje Phur pa 129 Sam VAN SCHAIK The Early Days of the Great Perfection........................................... 165 Charles MÜLLER The Yogacara Two Hindrances and their Reinterpretations in East Asia.................................................................................................... 207 Book Review Kurt A. BEHRENDT, The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhara. Handbuch der Orientalistik, section II, India, volume seventeen, Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2004 by Gérard FUSSMAN............................................................................. 237 Notes on the Contributors............................................................................ 251 THE ORAL TRANSMISSION OF EARLY BUDDHIST LITERATURE1 ALEXANDER WYNNE Two theories have been proposed to explain the oral transmission of early Buddhist literature. Some scholars have argued that the early literature was not rigidly fixed because it was improvised in recitation, whereas others have claimed that word for word accuracy was required when it was recited. This paper examines these different theories and shows that the internal evi- dence of the Pali canon supports the theory of a relatively fixed oral trans- mission of the early Buddhist literature. 1. Introduction Our knowledge of early Buddhism depends entirely upon the canoni- cal texts which claim to go back to the Buddha’s life and soon afterwards. But these texts, contained primarily in the Sutra and Vinaya collections of the various sects, are of questionable historical worth, for their most basic claim cannot be entirely true — all of these texts, or even most of them, cannot go back to the Buddha’s life. -

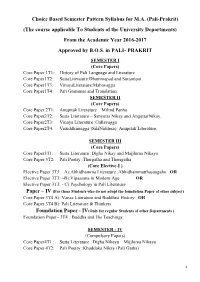

Pali-Prakrit) (The Course Applicable to Students of the University Departments) from the Academic Year 2016-2017 Approved by B.O.S

Choice Based Semester Pattern Syllabus for M.A. (Pali-Prakrit) (The course applicable To Students of the University Departments) From the Academic Year 2016-2017 Approved by B.O.S. in PALI- PRAKRIT SEMESTER I (Core Papers) Core Paper 1T1: History of Pali Language and Literature Core Paper1T2: SuttaLiterature:Dhammapad and Suttanipat Core Paper1T3: VinayaLiterature:Mahavagga. Core Paper1T4: Pali Grammar and Translation SEMESTER II (Core Papers) Core Paper 2T1: Anupitak Literature – Milind Panho Core Paper2T2: Sutta Literature – Sanyutta Nikay and AnguttarNikay. Core Paper2T3: Vinaya Literature :Cullavagga Core Paper2T4: Visuddhimagga (SilaNiddesa): Anupitak Literature. SEMESTER III (Core Papers) Core Paper3T1: Sutta Literature :Digha Nikay and Majjhima Nikaya Core Paper 3T2: Pali Poetry :Thergatha and Therigatha. (Core Elective-I ) Elective Paper 3T3: –A):Abhidhamma Literature :Abhidhammatthasangaho OR Elective Paper 3T3: –B):Vipassana in Modern Age OR Elective Paper 3T3: - C) Psychology in Pali Literature Paper – IV (For those Students who do not adopt the foundation Paper of other subject) Core Paper 3T4 A): Vansa Literature and Buddhist History OR Core Paper 3T4 B): Pali Literature & Thinkers Foundation Paper - IV(Only for regular Students of other Departments ) Foundation Paper– 3T4 : Buddha and His Teachings SEMESTER - IV (Compulsory Papers) Core Paper4T1 : Sutta Literature : Digha Nikaya – Mijjhima Nikaya Core Paper 4T2: Pali Poetry :Khuddaka Nikay (Pali Gatha) 1 (Core Elective-II ) Elective Paper 4T3: –A) Vinaypitaka – Patimokkha OR Elective Paper 4T3: –B) Modern Pali Literature OR Elective Paper 4T3: - C) Atthakatha Literature Paper – IV (For those Students who do not adopt the foundation Paper of other subject) Core Paper 4T4: -A): Comparative Linguistics and Essay OR Core Paper 4T4: -B): Propagation of Pali Literature Foundation Paper - IV(Only for regular Students of other Departments ) Foundation Paper - 4T4: - Pali Language and Literature University of Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur M.A. -

The Founding of Buddhism

IV The Founding of Buddhism 1. THE LIFE OF THE BUDDHA Siddhartha of the Gautama clan, later called the Buddha, or “the enlightened one,” began life in the foothills of the Himalayas, where his people, the Sakyas, were primarily rice farmers. The Sakyas formed the small city-state of Kapilavastu with an oligarchic republican constitution, under the hegemony of the powerful Magadha and Kosala Kingdoms to the south.1 Siddhartha traveled south to study, and so, after his Enlightenment, he first spread his doctrines in Northeastern India, south of the Ganges, west of Bhagalpur, and east of the Son River—South Bihar, nowadays. The people of this provincial area had been only partially assimilated to the Aryan culture and its Brahminic religion. Brahminism focused in the region of Northwestern India between the Ganges and Jumma Rivers, the older center of Indian civilization. Indeed, despite Buddhism’s anti-Brahmin cast, its chief rival in the early days may have been not Brahminism, but Jainism. Though Gautama was probably a Kshatriya, the rigidities of the Caste system were not yet established in the region, and Kapilavastu was oligarchic, so his father was not, as legend has it, a king.2 He left home in his youth against the will of his parents to become a wandering ascetic,3 an odd and irresponsible thing to do 1The location of Gautama’s homeland is confirmed in the Nikayas, which give the names of the places where each discourse was delivered. See Sutta Nipata 422, Digha Nikaya I 87 ff. 2The earliest scriptures do not provide an account of the life of the founder after the fashion of the Christian Gospels, but concentrate on preserving his words. -

Digha Nikaya Table of Contents

D¥gha Nikåya 3. Påthikavagga 1. S¥lakkhandhavagga 24. Påthika Sutta PTS Digha 1. Brahmajåla Sutta 25. Udumbarika Sutta 2. Såmaññaphala Sutta 26. Cakkavatti Sutta 3. Amba††ha Sutta 27. Aggañña Sutta 4. Soˆadaˆ∂a Sutta 28. Sampasådan¥ya Sutta Nikaya III 5. Kˆadanta Sutta 29. Påsådika Sutta 6. Mahåli Sutta 30. Lakkhaˆa Sutta 7. Jåliya Sutta 31. Si∫gåla Sutta 8. Mahås¥hanåda Sutta 32. Ó†ånå†iya Sutta 9. Po††hapåda Sutta PTS Digha Nikaya I 33. Sa∫g¥ti Sutta 10. Subha Sutta 34. Dasuttara Sutta 11. Keva††a Sutta 12. Lohicca Sutta 13. Tevijja Sutta Note that different text traditions may 2. Mahåvagga have somewhat different names for the same sutta. For example, the 8th sutta of 14. Mahåpadåna Sutta the D¥gha Nikåya is called "Mahå- 15. Mahånidåna Sutta s¥hanåda" in some texts but "Kassapa- 16. Mahåparinibbåna Sutta s¥hanåda" in others; the 11th sutta is called 17. Mahåsudassana Sutta "Keva††a" in some texts but "Kevaddha" in Nikaya II 18. Janavasabha Sutta others; the 24th sutta is called "Påthika" in 19. Mahågovinda Sutta some texts but "På†ika" in others; and the 20. Mahåsamaya Sutta 31st is variously called by the names 21. Sakkapañha Sutta "Si∫gåla", "Sigålaka", and "Sigålovåda". PTS Digha 22. Mahåsatipa††håna Sutta Such variations are generally a matter of 23. Påyåsi Sutta local preference or pronunciation, and do not indicate a radical difference in content. D¥gha Nikåya Contents by Sutta Title (Canonical order) I = PTS D¥gha Nikåya I, II = PTS D¥gha Nikåya II, III = PTS D¥gha Nikåya III TTP = Theravada Tipitaka Press Digha Nikaya (2010) Sutta Title Sutta Contents Sutta PTS TTP No. -

Selection of Suttas

TIPIṬAKA The Three Baskets Vinaya Piṭaka Sutta Piṭaka Abhidhamma Piṭaka The Discipline The Teachings The Philosophy (5 books) (5 collections) (7 books) Sutta Vibhanga Khandhaka Parivāra Dhammasaṅgaṇī Vibhaṅga Book of Expositions Division Chapter Summaries Compendium of States Book of Analysis Dhātukathā Puggalapaññati Māhavagga Cullavagga Discourse on Elements Human Types The Great Rules The Lesser Rules (10 chapters) (12 chapters) Kathāvatthu Yamaka Points of Controversy Book of Pairs Paṭṭhāna Conditional Relations Dīgha Nikāya Majjhima Nikāya Saṃyutta Nikāya Aṅguttara Nikāya Khuddaka Nikāya Long Discourses Middle-length Discourses Kindred Sayings Gradual Sayings Shorter Discourses (34 suttas in three vaggas) (152 suttas in 15 vaggas) (2,889 suttas in five vaggas)* (9,557 suttas in 11 nipatas) (15 books) Mūlapariyāya Vagga Sagāthā Vagga Ekaka Nipāta Khuddakapātha Dhammapada Sīlakkhanda Vagga The Root Discourse The section of Verses Book of the Ones The Short Passages Path of Dhamma The Perfect Net (423 verses arranged in 26 vaggas) Sīhanāda Vagga Duka Nipāta Udāna Itivuttaka The Lion’s Roar Nidāna Vagga Book of the Twos Mahā Vagga The section of Causation Verses of Uplift As it Was Said Opamma Vagga (8 vaggas, of 80 udānas of the Buddha) (112 short suttas in four nipātas) The Large Division Tika Nipāta Chapter of Similes Khandha Vagga Book of the Threes Suttanipāta Vimānavatthu Mūlapaṇṇāsa Mahāyamaka Vagga The Section on the Sutta Collection Celestial Mansions Pāṭika Vagga Catukka Nipāta Great Pairs Aggregates (5 vaggas containing 71 -

The Buddha and His Teachings

TheThe BuddhaBuddha andand HisHis TTeachingseachings Venerable Narada Mahathera HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. The Buddha and His Teachings Venerable Nārada Mahāthera Reprinted for free distribution by The Corporate Body of the Buddha Educational Foundation Taipei, Taiwan. July 1998 Namo Tassa Bhagavato Arahato Sammā-Sambuddhassa Homage to Him, the Exalted, the Worthy, the Fully Enlightened One Contents Introduction ................................................................................... vii The Buddha Chapter 1 From Birth to Renunciation ........................................................... 1 Chapter 2 His Struggle for Enlightenment ................................................. 13 Chapter 3 The Buddhahood ........................................................................... 25 Chapter 4 After the Enlightenment .............................................................. 33 Chapter 5 The Invitation to Expound the Dhamma .................................. 41 Chapter 6 Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta ................................................ 54 Chapter 7 The Teaching of the Dhamma ..................................................... 75 Chapter 8 The Buddha and His Relatives ................................................... 88 Chapter 9 The Buddha and His Relatives ................................................. 103 iii Chapter 10 The Buddha’s Chief Opponents and Supporters .................. 118 Chapter -

The Understanding of the Notion of Kingship in Early Buddhism and Manusmrti

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2019; 5(2): 114-117 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2019; 5(2): 114-117 The understanding of the notion of kingship in early © 2020 IJSR www.anantaajournal.com Buddhism and Manusmrti: A comparative account Received: 26-01-2019 Accepted: 28-02-2019 Asheesh Kumar and Jyoti Dr. Asheesh Kumar Assistant Professor, Abstract Department of Sanskrit, Rajdhani College University of The paper begins by revisiting a number of ideas related with the idea of kingship as portrayed within the Delhi, Delhi, India Digha Nikāya on one hand and the Manusmṛti on the other. We have analyzed a number of’ essays and books on the said subject matter and the illustration of the paper is based on our understanding of them. Dr. Jyoti Within the Digha Nikāya, there are certain ideals which if followed rigorously, can lead one towards the Assistant Professor, summum bonnum of one’s life (nibbāna). The main aim of this paper is to find out the central features of Department of Sanskrit, the king and his relationship with the society, focusing on the Digha Nikāya, and find its points of Shyama Prasad Mukherji College similarity and differences with the ideal society portrayed by Manu within the Manusmṛti. for Women University of Delhi, Our work procedure will be theoretical by nature, we will be referring to different texts, articles, online Delhi, India sources. The comments included within this work will be both descriptive and critical by nature. Key words: Buddhism, Manusmrti, Digha Nikāya Introduction We have picked up this particular topic for analysis in this paper because the constant presence of the kings (within the stories) portrayed within the Pali cannon made us wonder why the king had been such an important figure within the early Buddhist time. -

Dhammapadadhammapada AA Ttranslationranslation Ven

DhammapadaDhammapada AA TTranslationranslation Ven. Thanissaro, Bhikkhu HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. DDhhaammmmaappaaddaa TABLE OF CONTENTS.......................................................................................2 PREFACE: ANOTHER TRANSLATION OF THE DHAMMAPADA ....................................10 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................12 I : PAIRS.........................................................................................................24 1–2*................................................................................................................24 3–6..................................................................................................................25 7–8*................................................................................................................26 9–10................................................................................................................26 11–12*............................................................................................................26 13–14..............................................................................................................27 15–18*............................................................................................................28 19–20..............................................................................................................28 -

The Buddhist Perspective on the Beginning of the World, Nature, God, and Destruction

The Buddhist Perspective on the Beginning of the World, Nature, God, and Destruction By Widiyono The discussion on the beginning of the world, nature, God, and destruction is always an interesting topic. Especially, if we analyze the topic based on certain religious perspective, it will enrich our understanding about the topic as seen from the point of view of the religion which we refer to. There may be abundant resources which have described analytically about the beginning of the world, nature, God, and destruction from Islamic and Christian standpoints. However, it is hardly found any reading materials which clarify those subjects from the approach of Buddhism. Since there must be certain concepts found in the Buddhist scripture related to the subjects, obviously we can discuss those themes as viewed from Buddhism. By doing this, at least, we will understand what Buddhism would say with regard to those issues. In spite of the absence of the concept of God in Buddhism, we can see the view of the beginning of the world, nature, and destruction in the Buddhist texts. Therefore, in this paper I will examine how Buddhism perceives the concept of God, the beginning of the world, nature, and destruction by referring to the Buddhist scriptures. Here I will include the exposition of how Buddhist concept about the beginning of the world in relevance with the human role, nature, and the destruction of nature. As we see in our daily life, in this modern era we are facing various kinds of alarming problems. Environmental problems are just few of them.