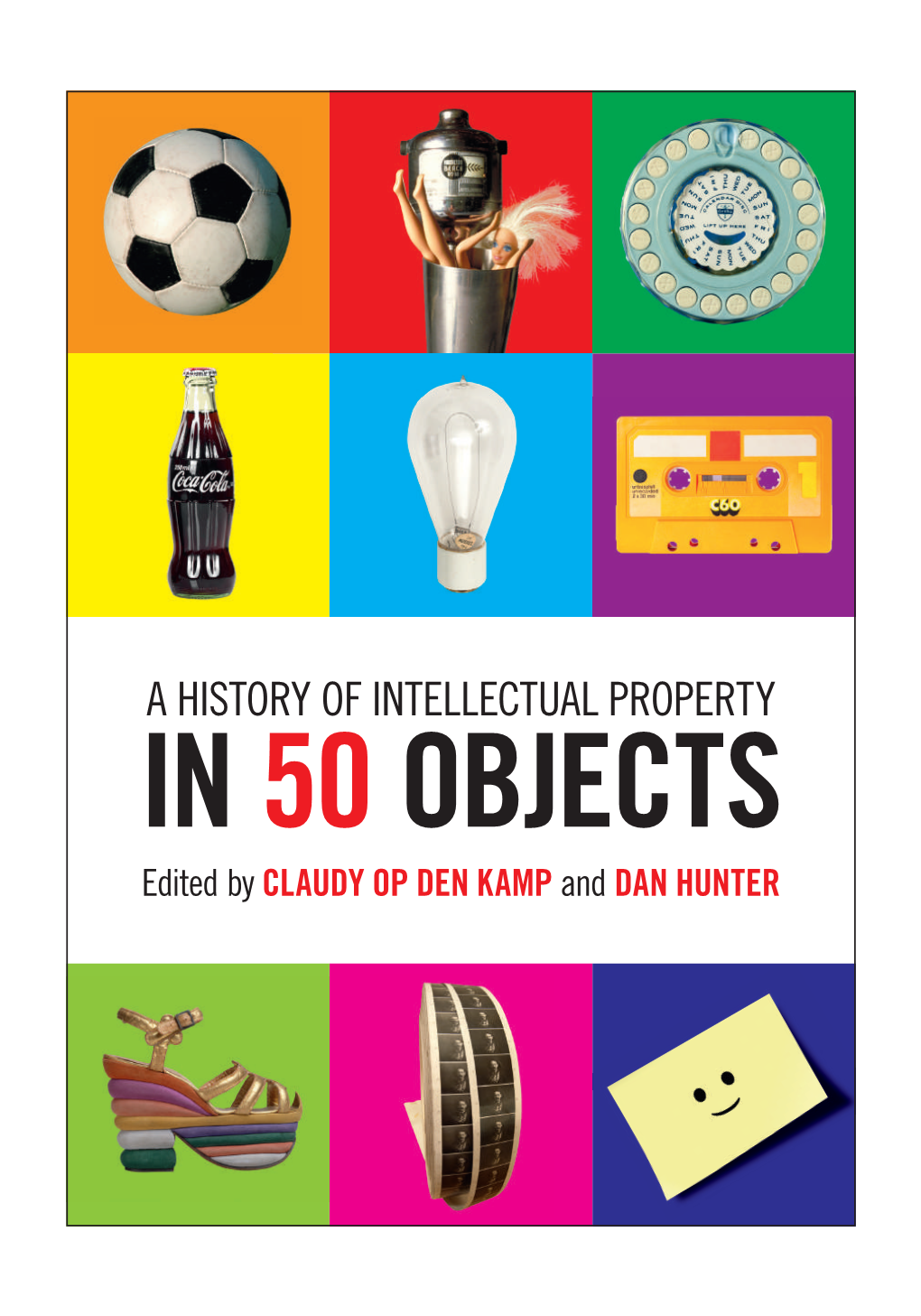

A HISTORY of INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY in 50 OBJECTS Edited by CLAUDY OP DEN KAMP and DAN HUNTER 6 Lithograph Amanda Scardamaglia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanization of the Printing Press Robin Roemer Western Oregon University, [email protected]

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU History of the Book: Disrupting Society from Student Scholarship Tablet to Tablet 6-2015 Chapter 08 - Mechanization of the Printing Press Robin Roemer Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/history_of_book Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Roemer, Robin. "Mechanization of the Printing Press." Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet. 2015. CC BY-NC. This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of the Book: Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 8 Mechanization of the Printing Press - Robin Roemer - One of the important leaps in the technology of copying text was the mechanization of printing. The speed and efficiency of printing was greatly improved through mechanization. This took several forms including: replacing wooden parts with metal ones, cylindrical printing, and stereotyping. The innovations of printing during the 19th century affected the way images were reproduced for illustrations as well as for type. These innovations were so influential on society because they greatly increased the ability to produce large quantities of work quickly. This was very significant for printers of newspapers, who were limited by the amount their press could produce in a short amount of time. Iron Printing Press One major step in improving the printing press was changing the parts from wood to metal. -

“Enoch” Lithograph

ARTICLE Blake’s “Enoch” Lithograph Robert N. Essick Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 14, Issue 4, Spring 1981, pp. 180-184 180 BLAKE'S "ENOCH" LITHOGRAPH ROBERT N. ESSICK ike many of Blake's separate graphics, If we assume the general accuracy of Cumberland's L "Enoch" offers several problems for those account, the "Block" or stone was white lias, a who wish to determine its exact medium, date, limestone from an area near Bath in southwestern and the circumstances surrounding its production. England, rather than the German Kellheim stone used Even the subject of Blake's only known lithograph by Alois Senefelder in the lithographic process he was not discovered until 1936.l My purpose here is invented in the mid-1790s.1' Instead of using to review what we know about the techniques Blake lithographic chalk or ink, Blake drew his design used to create "Enoch" and present some new informa- with a mixture of asphaltum and linseed oil which, tion on its relationship to the history of early if not the acid resist he actually used in his lithography in England. copperplate relief etchings, must have been a liquid with very similar physical properties. Besides the The pen and ink inscription (illus. 1) on the chemical differences between this mixture and verso of an impression of "Enoch" in the collection lithographic ink,5 Blake's material was probably of Mr. Edward Croft-Murray (illus. 2) would seem to more glutinous and would have to be heated so as to offer a description of how the print was made. -

Trevor Ridsdale Serials - Vol.11, No.1, March 1998

The modern printing process Trevor Ridsdale Serials - Vol.11, no.1, March 1998 Trevor Ridsdale This article looks at how printing Modem printing presses use state of the art technology, are fully processesfor academic books and automated and capable of printing up to four colours on both sides journals lzave evolved and how of the sheet simultaneously together with a variety of varnish desk top publishing (nunipdating coatings, at speeds of up to 16,000 impressions per hour. text and inuges electronically) has All the press functions are controlled from a central console led to computer to press printing using sophisticated computer technology. and digital priiiting technologies. Overview An overview of how the production of text and illustrations on paper evolved, gives a clearer understanding of how ink is transferred onto paper today. The Chinese were using wood blocks by the 6th century AD, but in Europe printing was unknown until the 14th century. A century later in Germany Johames Gutenberg was using movable type. William Caxton introduced printing to England. The next significant changes came in the 19th century, steam power replacing hand operated presses. Hand composition of type was replaced by machines operated by a keyboard. Linotype, a hot metal process (this produces a solid line of type known as a slug used in newspapers, magazines and books) was invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler in 1886 and commonly used until the early 1980s. Although these advances speeded up the operation of composing forms of lead type, and steam power followed later by electricity made for longer 'runs', the actual process still involved pressing the inked type onto paper, by the process known as letterpress. -

NGA | 2014 Annual Report

NATIO NAL G ALLERY OF ART 2014 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION Juliet C. Folger BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Marina Kellen French (as of 30 September 2014) Frederick W. Beinecke Morton Funger Chairman Lenore Greenberg Earl A. Powell III Rose Ellen Greene Mitchell P. Rales Frederic C. Hamilton Sharon P. Rockefeller Richard C. Hedreen Victoria P. Sant Teresa Heinz Andrew M. Saul Helen Henderson Benjamin R. Jacobs FINANCE COMMITTEE Betsy K. Karel Mitchell P. Rales Linda H. Kaufman Chairman Mark J. Kington Jacob J. Lew Secretary of the Treasury Jo Carole Lauder David W. Laughlin Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Chairman President Victoria P. Sant Edward J. Mathias Andrew M. Saul Robert B. Menschel Diane A. Nixon AUDIT COMMITTEE John G. Pappajohn Frederick W. Beinecke Sally E. Pingree Chairman Tony Podesta Mitchell P. Rales William A. Prezant Sharon P. Rockefeller Diana C. Prince Victoria P. Sant Robert M. Rosenthal Andrew M. Saul Roger W. Sant Mitchell P. Rales Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II TRUSTEES EMERITI Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. Leonard L. Silverstein Alexander M. Laughlin Albert H. Small David O. Maxwell Benjamin F. Stapleton John Wilmerding Luther M. Stovall Alexa Davidson Suskin EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Christopher V. Walker Frederick W. Beinecke Diana Walker President William L Walton Earl A. Powell III John R. West Director Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Dian Woodner Chief Justice of the Franklin Kelly United States Deputy Director and Chief Curator HONORARY TRUSTEES’ William W. McClure COUNCIL Treasurer (as of 30 September 2014) Darrell R. -

Prints and Books

Aus dem Kunstantiquariat: prints and books c.g. boerner in collaboration with harris schrank fine prints Martin Schongauer ca. 1450 Colmar – Breisach 1491 1. Querfüllung auf hellem Grund – Horizontal Ornament mid-1470s engraving; 57 x 73 mm (2 ¼ x 2 ⅞ inches) Bartsch 116; Lehrs and Hollstein 107 provenance Jean Masson, Amiens and Paris (not stamped, cf. Lugt 1494a); his sale Gilhofer & Ranschburg, Lucerne (in collaboration with L. Godefroy and L. Huteau, Paris), November 16–17, 1926 Carl and Rose Hirschler, née Dreyfus, Haarlem (Lugt 633a), acquired from Gilhofer & Ranschburg in May 1928; thence by descent exhibition B.L.D. Ihle and J.C. Ebbinge Wubben, Prentkunst van Martin Schongauer, Albrecht Dürer, Israhel van Meckenem. Uit eene particuliere verzameling, exhibition catalogue, Museum Boijmans, Rotterdam, 1955, p. 10, no. 8 literature Harmut Krohm and Jan Nicolaisen, Martin Schongauer. Druckgraphik im Berliner Kupferstichkabi- nett, exhibition catalogue, Berlin 1991, no. 32 Tilman Falk and Thomas Hirthe, Martin Schongauer. Das Kupferstichwerk, exhibition catalogue, Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München, 1991, no. 107 Lehrs lists six impressions and Hollstein no more than eight, to which this one has to be added. Richard Field’s Census for the American collections lists only one impression in the Cooper- Hewitt Museum in New York. This is the smallest of Schongauer’s ornament prints. While the background remains white, the sophisticated shading makes the leaf appear to move back and forth within a shallow relief. Schongauer’s ornament prints can be divided into Blattornamente (leaf ornaments that show a large single leaf against a plain background, Lehrs 111–114) and Querfüllungen (oblong panel ornaments, Lehrs 107–110). -

The Invention of Lithography Alois Senefelder J

THE INVENTION OF LITHOGRAPHY ALOIS SENEFELDER J THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ^3p aioia S'tnrfcHitr THE INVENTION OF LITHOGRAPHY THE INVENTION OF LITHOGRAPHY BY ALOIS SENEFELDER TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL GERMAN BY W. J. MULLER NEW YORK: THE FUCHS & LANG MANUFACTURING COMPANY 191 I I COPYRIGHT, 191 I, BY THE FUCHS & LANG MANUFACTURING COMPANY NEW YORK AND LONDON Entered at Stationers' Hall^ London Library TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE ALOIS SENEFELDER, not only the inventor, but the father and perfecter of Lithography, wrote this story of his hfe and his in- vention in 1817. The translator has followed his style closely, because he felt that the readers would prefer to have this English edition represent Senefelder's original German faithfully. When Senefelder wrote, he had to invent many names for the processes, manipulation-methods, and tools. These terms have been translated literally even where modern practice has adopted other names. The original German edition carried the following title-page : — containing Cor- | a | of Stone-Printing "Complete Text-Book | rect Lucid Instruction for all Various Manipu- AND | IN its also lations ALL Branches and Methods | and a | its Origin Full History of this Art | from to the Present Day. Written Published Inventor of Lrrno- and | by the I Printing, Senefelder. a graphy and Chemical | Alois | With Preface by the General-Secretary of the Royal Acad- in Friederich | Director emy OF Sciences Munich, the | Schlichtegroll 1821 von Munich, | Obtainable from the I Author and from E. A. Fleischmann" I The book was dedicated by Senefelder to Maximilian Joseph, then King of Bavaria. -

Glasses for Lithography and Lithography for Glasses

Glasses for lithography and lithography for glasses Miroslav VLCEK Department of General and Inorganic Chemistry Faculty of Chemical Technology University of Pardubice, 532 10 Pardubice Czech Republic 1 Goals of IMI-NFG: •International Colaboration with Research Trust on 6 new Functionalities •Multimedia Glass Education delivered across the boundaries •Outreach/Networking Glass Lecture Series: prepared for and produced by the International Material Institute for New Functionality in Glass An NSF sponsored program – material herein not for sale Available at www.lehigh.edu/imi 2 Questions • What is lithography? What is glass? • Can glass be photosensitive? • Can glass be selectively etched/featured? If yes, how and what is the resolution limit? • Can a glass be applied in lithographic process and vice versa can lithography be applied to structure glasses? 3 Lithography – what does it mean? in ancient Greek: lithos = stones graphia = to write discovered by Alois Senefelder (Prague, Bohemia currently Czech Republic) in 1796 • oil-based image painted on the smooth surface of limestone • nitric acid (HNO3) emulsified with gum arabic burns the image only where surface unpainted and gum arabic sticks to the resulting etched area. • printing – water adheres to the gum arabic surface and avoids the oily parts, oily ink used for printing is doing exactly opposite, positive http://sweb.cz/galerie.litografie/ image is transferred on paper 4 „Technical“ understanding of term lithography these days: formation of 3-D relief images in a film on the substrate -

Alois Senefelder – the Invention and Early Days of Lithography

Alois Senefelder – The Invention and Early Days of Lithography In the spring or summer of 1796, a dejected young man wandered along the shores of the River Iser near Munich. His father had died a few years earlier and his mother was left alone with eight children. He had therefore been forced to interrupt his legal studies at the University of Ingolstadt in Bavaria. Having failed as an actor, he had had some success as a playwright. But it was difficult to find publishers and he had decided to print the play himself. The only problem was that he did not have the money to buy the necessary equipment. Alois Senefelder – as the young man was called – tried to find cheaper ways to do the printing. He had tried writing in reverse on copper plates, but this was time consuming and he could not afford enough plates. In his quandary, he had even considered serving as a substitute for an acquaintance in the army. This would get him 200 guilders with which he would be able to afford to continue his experiments. But he was turned down. Because he was born in Prague (1771), Senefelder was considered an Austrian, and Bavaria was at war with Austria. On his walk, he met a friend who suggested a glass of beer in the nearby Wollgarten. It was here that Senefelder came across a slab of Solnhofen limestone, which he picked up. He scraped the stone with his knife, revealing the stone’s texture. This gave him the idea that it might be possible to etch out raised figures, letters or notes on the stone, and that these might be printed in the same way that one prints with wooden boards or metal plates. -

Lithography Days International

III. INTERNATIONAL LITHOGRAPHY DAYS EXHIBITIONS LITHO LIVE Lithography Days Patron: Prof. Dr. Claus Hip On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of lithography workshop Lithography parkours: Feel and experience materiality and Presentations and lithography demonstrations from all over President: Maja Grassinger - Munich stone print, the Munich Künstlerhaus Foundation is spirit the world International Workshop Manager: Franz Hoke showing a wide range of lithographic exhibits. III. In seven stations visitors can get acquainted with the technology of Per Anderson (Mexico), Felix Bauer (Germany), Jim Berggren (Swe- lithography under the slogan „Material needs to be understood“. From 29th August to 02nd September 2018, the Munich Competition den), Cyril Bihain (Belgium), Nina Bondeson (Sweden), Hugo Bos Impressions around the used materials are made discoverable, Künstlerhaus presents lithography in a unique event and (Netherlands), Łukasz Butowski (Poland), Gertjan Forrer, (Nether- For lithography artists from all over the world, a competition with in order to perceive these with all senses (stones, chalks, ink, opens the entire house! lands), Armando Gomez (Mexico), Primin Hagen (Austria), Ernst three prizes was awarded. Jury: Melissa Mayer Galbraith, Franz fats, oils, water, pigments, paper, etc.). Hanke (Switzerland), Róbert Jančovič jr. (Slovakia), Christine Hoke, Prof. Dr. Claus Hipp, Prof. Karl Imhof, Tom Kristen, Gesa The Lithography Days 2018 gather artists, printers, professionals, Katscher (Austria), Maarten Kentgens (Netherlands), Petr Puell. The works of the competitors will be exhibited. enthusiasts and interested laymen from around the world. They Korbelar (Czech Republic), Ingrid Ledent (Belgium), Aoife Mc- should provide an exciting forum to illuminate current positions of Exhibition of scholarship work Garrigle (Scotland), Nobuhiko Numazaki (Austria), Gilberto lithography and to discover, test and experience their possibilities. -

Creativity Anoiko 2011

Creativity Anoiko 2011 PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 27 Mar 2011 10:09:26 UTC Contents Articles Intelligence 1 Convergent thinking 11 Divergent thinking 12 J. P. Guilford 13 Robert Sternberg 16 Triarchic theory of intelligence 20 Creativity 23 Ellis Paul Torrance 42 Edward de Bono 46 Imagination 51 Mental image 55 Convergent and divergent production 62 Lateral thinking 63 Thinking outside the box 65 Invention 67 Timeline of historic inventions 75 Innovation 111 Patent 124 Problem solving 133 TRIZ 141 Creativity techniques 146 Brainstorming 148 Improvisation 154 Creative problem solving 158 Intuition (knowledge) 160 Metaphor 164 Ideas bank 169 Decision tree 170 Association (psychology) 174 Random juxtaposition 174 Creative destruction 175 References Article Sources and Contributors 184 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 189 Article Licenses License 191 Intelligence 1 Intelligence Intelligence is a term describing one or more capacities of the mind. In different contexts this can be defined in different ways, including the capacities for abstract thought, understanding, communication, reasoning, learning, planning, emotional intelligence and problem solving. Intelligence is most widely studied in humans, but is also observed in animals and plants. Artificial intelligence is the intelligence of machines or the simulation of intelligence in machines. Numerous definitions of and hypotheses about intelligence have been proposed since before the twentieth century, with no consensus reached by scholars. Within the discipline of psychology, various approaches to human intelligence have been adopted. The psychometric approach is especially familiar to the general public, as well as being the most researched and by far the most widely used in practical settings.[1] History of the term Intelligence derives from the Latin verb intelligere which derives from inter-legere meaning to "pick out" or discern. -

The Invention of Lithography

In I CD CO "(0 fip aioi0 SenefelHer Translated from the Original German by J. W. MULLER THE INVENTION OF LITHOGRAPHY Cloth 410 $5.00 Postpaid THE FUCHS & LANG MANUFACTURING CO. NEW YORK THE INVENTION OF LITHOGRAPHY THE LITHOGRAPHY BY ALOIS SENEFELDER TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL GERMAN BY J. W. MULLER NEW YORK: THE FUCHS & LANG MANUFACTURING COMPANY 1911 COPYRIGHT, I9II, BY THE FUCHS & LANG MANUFACTURING COMPANY NEW YORK AND LONDON Entered at Stationers' Hall, London TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE SENEFELDER, not only the inventor, but the father and wrote this of his life and his in- ALOISperfecter of Lithography, story he vention in 1817. The translator has followed his style closely, because felt that the readers would prefer to have this English edition represent Senefelder's original German faithfully. When Senefelder wrote, he had to invent many names for the processes, have been translated manipulation-methods, and tools. These terms other names. literally even where modern practice has adopted The original German edition carried the following title-page : OF STONE-PRINTING CONTAINING A COR- "COMPLETE TEXT-BOOK | | RECT AND LUCID INSTRUCTION FOR ALL VARIOUS MANIPU- | IN ITS AND METHODS AND ALSO A ALL BRANCHES | LATIONS | FULL HISTORY OF THIS ART FROM ITS ORIGIN TO THE PRESENT | DAY. WRITTEN AND PUBLISHED BY THE INVENTOR OF LITHO- | | ALOIS SENEFELDER. WITH A AND CHEMICAL | GRAPHY PRINTING, | PREFACE BY THE GENERAL-SECRETARY OF THE ROYAL ACAD- IN THE DIRECTOR FRIEDERICH EMY OF SCIENCES | | MUNICH, l82I OBTAINABLE FROM THE VON SCHLICHTEGROLL | | MUNICH, AUTHOR AND FROM E. A. FLEISCHMANN" The book WM dedicated by Senefelder to Maximilian Jcweph, then King of Bavaria July, 19". -

The Origin and Performance History of Carl Maria Von Weber's Das Waldmädchen (1800) Bama Lutes Deal

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 The Origin and Performance History of Carl Maria Von Weber's Das Waldmädchen (1800) Bama Lutes Deal Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE ORIGIN AND PERFORMANCE HISTORY OF CARL MARIA VON WEBER’S DAS WALDMÄDCHEN (1800) By BAMA LUTES DEAL A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 Bama Lutes Deal All Rights Reserved The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Bama Lutes Deal defended on 1 April 2005. ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation ___________________________________ Douglas Fisher Outside Committee Member ___________________________________ Charles Brewer Committee Member ___________________________________ Jeffery Kite-Powell Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful for the education and encouragement I received from the faculty and administration of The Florida State University College of Music, and for the love, patience, and support of my dear family, colleagues, and friends. Collectively, their words and deeds contributed greatly to this document and helped me grow as a scholar and a musician. I thank my dissertation advisor, Douglass Seaton, for his uncompromising principles and many examples of scholarly work. I have benefited from his insistence on carefully organized writing and clear logic. The members of my committee also provided thorough editorial guidance as I prepared this document.