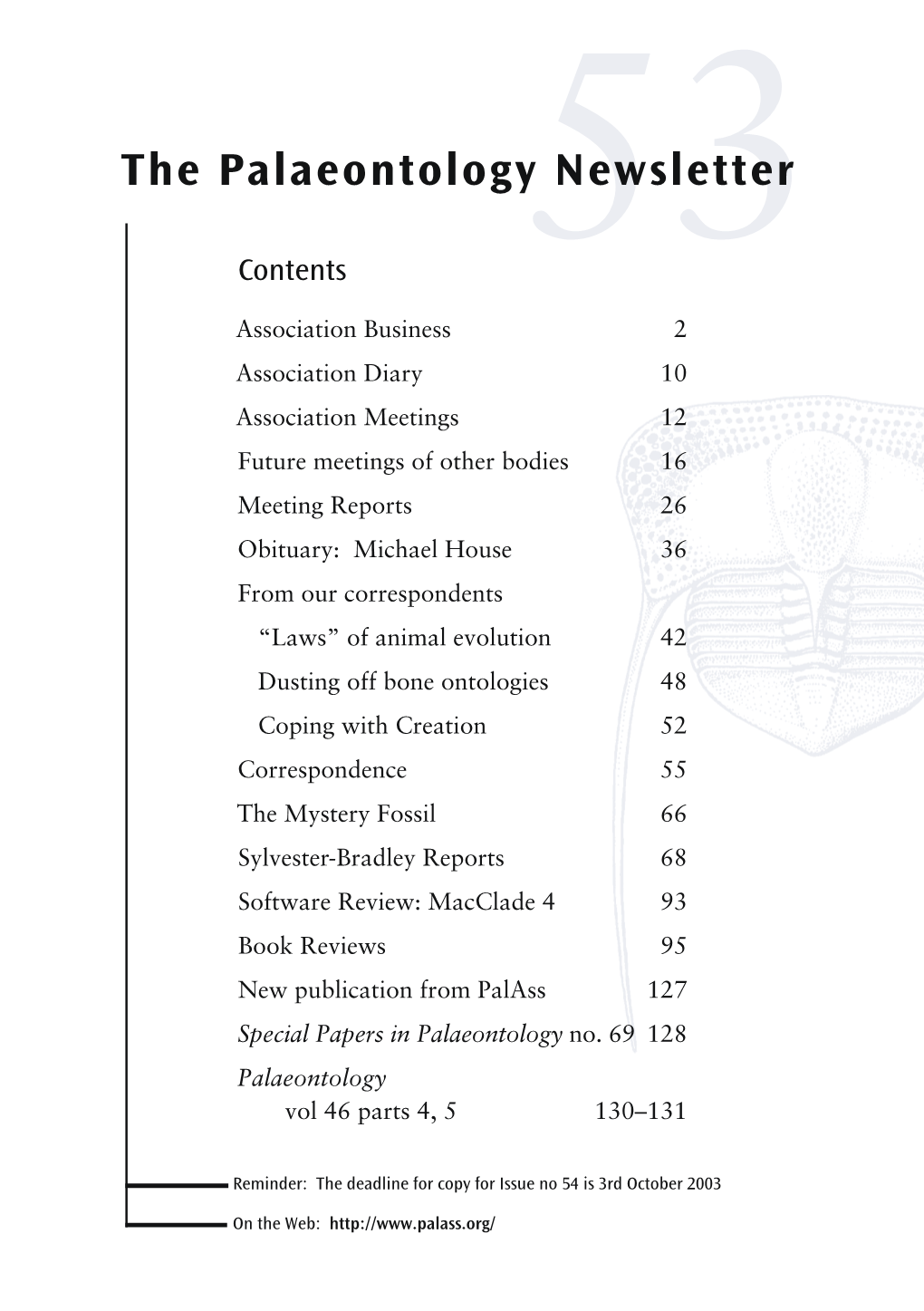

Newsletter Number 53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JVP 26(3) September 2006—ABSTRACTS

Neoceti Symposium, Saturday 8:45 acid-prepared osteolepiforms Medoevia and Gogonasus has offered strong support for BODY SIZE AND CRYPTIC TROPHIC SEPARATION OF GENERALIZED Jarvik’s interpretation, but Eusthenopteron itself has not been reexamined in detail. PIERCE-FEEDING CETACEANS: THE ROLE OF FEEDING DIVERSITY DUR- Uncertainty has persisted about the relationship between the large endoskeletal “fenestra ING THE RISE OF THE NEOCETI endochoanalis” and the apparently much smaller choana, and about the occlusion of upper ADAM, Peter, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; JETT, Kristin, Univ. of and lower jaw fangs relative to the choana. California, Davis, Davis, CA; OLSON, Joshua, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los A CT scan investigation of a large skull of Eusthenopteron, carried out in collaboration Angeles, CA with University of Texas and Parc de Miguasha, offers an opportunity to image and digital- Marine mammals with homodont dentition and relatively little specialization of the feeding ly “dissect” a complete three-dimensional snout region. We find that a choana is indeed apparatus are often categorized as generalist eaters of squid and fish. However, analyses of present, somewhat narrower but otherwise similar to that described by Jarvik. It does not many modern ecosystems reveal the importance of body size in determining trophic parti- receive the anterior coronoid fang, which bites mesial to the edge of the dermopalatine and tioning and diversity among predators. We established relationships between body sizes of is received by a pit in that bone. The fenestra endochoanalis is partly floored by the vomer extant cetaceans and their prey in order to infer prey size and potential trophic separation of and the dermopalatine, restricting the choana to the lateral part of the fenestra. -

A New Xinjiangchelyid Turtle from the Middle Jurassic of Xinjiang, China and the Evolution of the Basipterygoid Process in Mesozoic Turtles Rabi Et Al

A new xinjiangchelyid turtle from the Middle Jurassic of Xinjiang, China and the evolution of the basipterygoid process in Mesozoic turtles Rabi et al. Rabi et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:203 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/203 Rabi et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:203 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/203 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access A new xinjiangchelyid turtle from the Middle Jurassic of Xinjiang, China and the evolution of the basipterygoid process in Mesozoic turtles Márton Rabi1,2*, Chang-Fu Zhou3, Oliver Wings4, Sun Ge3 and Walter G Joyce1,5 Abstract Background: Most turtles from the Middle and Late Jurassic of Asia are referred to the newly defined clade Xinjiangchelyidae, a group of mostly shell-based, generalized, small to mid-sized aquatic froms that are widely considered to represent the stem lineage of Cryptodira. Xinjiangchelyids provide us with great insights into the plesiomorphic anatomy of crown-cryptodires, the most diverse group of living turtles, and they are particularly relevant for understanding the origin and early divergence of the primary clades of extant turtles. Results: Exceptionally complete new xinjiangchelyid material from the ?Qigu Formation of the Turpan Basin (Xinjiang Autonomous Province, China) provides new insights into the anatomy of this group and is assigned to Xinjiangchelys wusu n. sp. A phylogenetic analysis places Xinjiangchelys wusu n. sp. in a monophyletic polytomy with other xinjiangchelyids, including Xinjiangchelys junggarensis, X. radiplicatoides, X. levensis and X. latiens. However, the analysis supports the unorthodox, though tentative placement of xinjiangchelyids and sinemydids outside of crown-group Testudines. A particularly interesting new observation is that the skull of this xinjiangchelyid retains such primitive features as a reduced interpterygoid vacuity and basipterygoid processes. -

Tagged Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle

Opinions expressedherein are those of the individual authors and do not necessar- ily representthe views of the TexasARM UniversitySea Grant College Program or the National SeaGrant Program.While specificproducts have been identified by namein various papers,this doesnot imply endorsementby the publishersor the sponsors. $20.00 TAMU-SG-89-1 05 Copies available from: 500 August 1989 Sca Grant College Program NA85AA-D-SG128 Texas ARM University A/I-I P.O. Box 1675 Galveston, Tex. 77553-1675 Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle Biology, Conservation and Management ~88<!Mgpgyp Sponsors- ~88gf-,-.g,i " ' .Poslfpq National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Center Galveston Laboratory Departmentof Marine Biology Texas A&M University at Galveston October 1-4, 1985 Galveston, Texas Edited and updated by Charles W. Caillouet, Jr. National Marine Fisheries Service and Andre M. Landry, Jr. Texas A&M University at Galveston NATIONALSEA GRANT DEPOSITORY PELLLIBRARY BUILDING TAMU-~9 I05 URI,NARRAGANSETT BAYCAMPUS August 7989 NARRAGANSETI, R I02882 Publicationof this documentpartially supportedby Institutional GrantNo. NA85AA-D-SGI28to the TexasARM UniversitySea Grant CollegeProgram by the NationalSea Grant Program,National Oceanicand AtmosphericAdministration, Department of Commerce. jbr Carole Hoover Allen and HEART for dedicatedefforts tmuard Kemp'sridley sea turtle conservation Table of Conteuts .v Preface CharlesW. Caillouet,jr. and Andre M. Landry, Jr, Acknowledgements. vl SessionI -Historical -

Sequence of Post-Moult Exoskeleton Hardening Preserved in a Trilobite Mass Moult Assemblage from the Lower Ordovician Fezouata Konservat-Lagerstätte, Morocco

Editors' choice Sequence of post-moult exoskeleton hardening preserved in a trilobite mass moult assemblage from the Lower Ordovician Fezouata Konservat-Lagerstätte, Morocco HARRIET B. DRAGE, THIJS R.A. VANDENBROUCKE, PETER VAN ROY, and ALLISON C. DALEY Drage, H.B., Vandenbroucke, T.R.A., Van Roy, P., and Daley, A.C. 2019. Sequence of post-moult exoskeleton hardening preserved in a trilobite mass moult assemblage from the Lower Ordovician Fezouata Konservat-Lagerstätte, Morocco. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 64 (2): 261–273. Euarthropods have a tough exoskeleton that provides crucial protection from predation and parasitism. However, this is restrictive to growth and must be periodically moulted. The moulting sequence is well-known from extant arthropods, consisting of: (i) the long inter-moult stage, in which no changes occur to the hardened exoskeleton; (ii) the pre-moult stage where the old exoskeleton is detached and the new one secreted; (iii) exuviation, when the old exoskeleton is moulted; and (iv) the post-moult stage during which the new exoskeleton starts as soft, thin, and partially compressed and gradually hardens to the robust exoskeleton of the inter-moult stage. Trilobite fossils typically consist of inter-moult carcasses or moulted exuviae, but specimens preserving the post-moult stage are rare. Here we describe nine specimens assigned to Symphysurus ebbestadi representing the first group of contemporaneous fossils collected that preserve all key stages of the moulting process in one taxon, including the post-moult stage. They were collected from a single lens in the Tremadocian part of the Fezouata Shale Formation, Morocco. Based on cephalic displacement and comparison to other trilobite moults, one specimen appears to represent a moulted exoskeleton. -

NM IF C3 4 16 Fossil Imprint

FOSSIL IMPRINT • vol. 72 • 2016 • no. 3-4 • pp. 183–201 (formerly ACTA MUSEI NATIONALIS PRAGAE, Series B – Historia Naturalis) HIPPOPOTAMODON ERYMANTHIUS (SUIDAE, MAMMALIA) FROM MAHMUTGAZI, DENIZLI-ÇAL BASIN, TURKEY MARTIN PICKFORD Sorbonne Universités – CR2P, MNHN, CNRS, UPMC – Paris VI, 8, rue Buffon, 75005, Paris, France; e-mail: [email protected]. Pickford, M. (2016): Hippopotamodon erymanthius (Suidae, Mammalia) from Mahmutgazi, Denizli-Çal Basin, Turkey. – Fossil Imprint, 72(3-4): 183–201, Praha. ISSN 2533-4050 (print), ISSN 2533-4069 (on-line). Abstract: The Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde in Karlsruhe houses an interesting collection of Turolian mammals from Mahmutgazi, Turkey, among which is a comprehensive sample of the large suid, Hippopotamodon erymanthius. The fossils plot out within the range of metric variation of H. erymanthius from Pikermi and Samos, Greece, but lie at the lower end of the range. Like the suids from these sites, the Mahmutgazi specimens lack the first premolar. Overall, the Mahmutgazi sample is metrically and morphologically close to the material from Akkaşdağı, Turkey. The upper and lower third molars and fourth premolars are, on average, smaller than those of Hippopotamodon major from Luberon, France (MN 13). Two undescribed fossils of H. ery- manthius from Pikermi are housed at the SMNK, and are included in this paper in order to fill out the data base for the species at this locality. The chronological position, palaeoecology and sexual dimorphism of the Mahmutgazi suids are discussed. Key words: Suidae, Late Miocene, Turkey, Hippopotamodon, biochronology, palaeoecology, sexual dimorphism Received: October 10, 2016 | Accepted: November 28, 2016 | Issued: December 30, 2016 Introduction (2010) mentions suids at the site, and correlated it to MN 11–12 (Early to Middle Turolian). -

Chapter 1 - Introduction

EURASIAN MIDDLE AND LATE MIOCENE HOMINOID PALEOBIOGEOGRAPHY AND THE GEOGRAPHIC ORIGINS OF THE HOMININAE by Mariam C. Nargolwalla A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright by M. Nargolwalla (2009) Eurasian Middle and Late Miocene Hominoid Paleobiogeography and the Geographic Origins of the Homininae Mariam C. Nargolwalla Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto 2009 Abstract The origin and diversification of great apes and humans is among the most researched and debated series of events in the evolutionary history of the Primates. A fundamental part of understanding these events involves reconstructing paleoenvironmental and paleogeographic patterns in the Eurasian Miocene; a time period and geographic expanse rich in evidence of lineage origins and dispersals of numerous mammalian lineages, including apes. Traditionally, the geographic origin of the African ape and human lineage is considered to have occurred in Africa, however, an alternative hypothesis favouring a Eurasian origin has been proposed. This hypothesis suggests that that after an initial dispersal from Africa to Eurasia at ~17Ma and subsequent radiation from Spain to China, fossil apes disperse back to Africa at least once and found the African ape and human lineage in the late Miocene. The purpose of this study is to test the Eurasian origin hypothesis through the analysis of spatial and temporal patterns of distribution, in situ evolution, interprovincial and intercontinental dispersals of Eurasian terrestrial mammals in response to environmental factors. Using the NOW and Paleobiology databases, together with data collected through survey and excavation of middle and late Miocene vertebrate localities in Hungary and Romania, taphonomic bias and sampling completeness of Eurasian faunas are assessed. -

(Suidae, Artiodactyla) from the Upper Miocene of Hayranlı-Haliminhanı, Turkey

Turkish Journal of Zoology Turk J Zool (2013) 37: 106-122 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/zoology/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/zoo-1202-4 Microstonyx (Suidae, Artiodactyla) from the Upper Miocene of Hayranlı-Haliminhanı, Turkey 1 2 3, Jan VAN DER MADE , Erksin GÜLEÇ , Ahmet Cem ERKMAN * 1 Spanish National Research Council, National Museum of Natural Sciences, Madrid, Spain 2 Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Languages, History, and Geography, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey 3 Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Science and Literature, Ahi Evran University, Kırşehir, Turkey Received: 05.02.2012 Accepted: 11.07.2012 Published Online: 24.12.2012 Printed: 21.01.2013 Abstract: The suid remains from localities 58-HAY-2 and 58-HAY-19 in the Late Miocene Derindere Member of the İncesu Formation in the Hayranlı-Haliminhanı area (Sivas, Turkey) are described and referred to as Microstonyx major (Gervais, 1848–1852). Microstonyx shows changes in incisor morphology, which are interpreted as a further adaptation to rooting. This occurred probably in a short period between 8.7 and 8.121 Ma ago and possibly is a reaction to environmental change. The incisor morphology in locality 58-HAY-2 suggests that it is temporally close to this change, which would imply that this locality and the lithostratigraphically lower 58-HAY-19 belong to the lower part of MN11 and not to MN12. The findings are discussed in the regional context and contribute to the knowledge of the Anatolian fossil mammals. Key words: Suidae, Microstonyx, rooting, ecology, Late Miocene 1. Introduction 1.1. Location and stratigraphy The first of the Hayranlı-Haliminhanı fossil localities was Anatolia lies at the intersection of Asia, Europe, and Afro- discovered in 1993 by members of the Vertebrate Fossils Arabia, and its geology has been subject to the plate tectonic Research Project, a collaborative survey effort. -

Available Generic Names for Trilobites

AVAILABLE GENERIC NAMES FOR TRILOBITES P.A. JELL AND J.M. ADRAIN Jell, P.A. & Adrain, J.M. 30 8 2002: Available generic names for trilobites. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 48(2): 331-553. Brisbane. ISSN0079-8835. Aconsolidated list of available generic names introduced since the beginning of the binomial nomenclature system for trilobites is presented for the first time. Each entry is accompanied by the author and date of availability, by the name of the type species, by a lithostratigraphic or biostratigraphic and geographic reference for the type species, by a family assignment and by an age indication of the type species at the Period level (e.g. MCAM, LDEV). A second listing of these names is taxonomically arranged in families with the families listed alphabetically, higher level classification being outside the scope of this work. We also provide a list of names that have apparently been applied to trilobites but which remain nomina nuda within the ICZN definition. Peter A. Jell, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane, Queensland 4101, Australia; Jonathan M. Adrain, Department of Geoscience, 121 Trowbridge Hall, Univ- ersity of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242, USA; 1 August 2002. p Trilobites, generic names, checklist. Trilobite fossils attracted the attention of could find. This list was copied on an early spirit humans in different parts of the world from the stencil machine to some 20 or more trilobite very beginning, probably even prehistoric times. workers around the world, principally those who In the 1700s various European natural historians would author the 1959 Treatise edition. Weller began systematic study of living and fossil also drew on this compilation for his Presidential organisms including trilobites. -

Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) and the Position of Systematics in Evolutionary Biology

Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) and the Position of Systematics in Evolutionary Biology by Paul David Polly B.A. (University of Texas at Austin) 1987 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Paleontology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA at BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor William A. Clemens, Chair Professor Kevin Padian Professor James L. Patton Professor F. Clark Howell 1993 Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) and the Position of Systematics in Evolutionary Biology © 1993 by Paul David Polly To P. Reid Hamilton, in memory. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ix Acknowledgments xi Chapter One--Revolution and Evolution in Taxonomy: Mammalian Classification Before and After Darwin 1 Introduction 2 The Beginning of Modern Taxonomy: Linnaeus and his Predecessors 5 Cuvier's Classification 10 Owen's Classification 18 Post-Darwinian Taxonomy: Revolution and Evolution in Classification 24 Kovalevskii's Classification 25 Huxley's Classification 28 Cope's Classification 33 Early 20th Century Taxonomy 42 Simpson and the Evolutionary Synthesis 46 A Box Model of Classification 48 The Content of Simpson's 1945 Classification 50 Conclusion 52 Acknowledgments 56 Bibliography 56 Figures 69 Chapter Two: Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) from the Early Eocene Four Mile Fauna and Their Biostratigraphic Implications 78 Abstract 79 Introduction 79 Materials and Methods 80 iv Systematic Paleontology 80 The Four Mile Fauna and Wasatchian Biostratigraphic Zonation 84 Conclusion 86 Acknowledgments 86 Bibliography 86 Figures 87 Chapter Three: A New Genus Eurotherium (Creodonta, Mammalia) in Reference to Taxonomic Problems with Some Eocene Hyaenodontids from Eurasia (With B. Lange-Badré) 89 Résumé 90 Abstract 90 Version française abrégéé 90 Introduction 93 Acknowledgments 96 Bibliography 96 Table 3.1: Original and Current Usages of Genera and Species 99 Table 3.2: Species Currently Included in Genera Discussed in Text 101 Chapter Four: The skeleton of Gazinocyon vulpeculus n. -

(Mammalia) from the French Locality of Aumelas (Hérault), with Possible New Representatives from the Late Ypresian

geodiversitas 2020 42 13 né – Car ig ni e vo P r e e s n a o f h t p h é e t S C l e a n i r o o z o m i e c – M DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION / PUBLICATION DIRECTOR: Bruno David, Président du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle RÉDACTEUR EN CHEF / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF : Didier Merle ASSISTANT DE RÉDACTION / ASSISTANT EDITOR : Emmanuel Côtez ([email protected]) MISE EN PAGE / PAGE LAYOUT : Emmanuel Côtez COMITÉ SCIENTIFIQUE / SCIENTIFIC BOARD : Christine Argot (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris) Beatrix Azanza (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid) Raymond L. Bernor (Howard University, Washington DC) Alain Blieck (chercheur CNRS retraité, Haubourdin) Henning Blom (Uppsala University) Jean Broutin (Sorbonne Université, Paris, retraité) Gaël Clément (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris) Ted Daeschler (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphie) Bruno David (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris) Gregory D. Edgecombe (The Natural History Museum, Londres) Ursula Göhlich (Natural History Museum Vienna) Jin Meng (American Museum of Natural History, New York) Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud (CIRAD, Montpellier) Zhu Min (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Pékin) Isabelle Rouget (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris) Sevket Sen (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, retraité) Stanislav Štamberg (Museum of Eastern Bohemia, Hradec Králové) Paul Taylor (The Natural History Museum, Londres, retraité) COUVERTURE / COVER : Made from the Figures of the article. Geodiversitas est indexé dans / Geodiversitas is indexed in: – Science -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

001-012 Primeras Páginas

PUBLICACIONES DEL INSTITUTO GEOLÓGICO Y MINERO DE ESPAÑA Serie: CUADERNOS DEL MUSEO GEOMINERO. Nº 9 ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH IN ADVANCES ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH IN ADVANCES planeta tierra Editors: I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and Ciencias de la Tierra para la Sociedad D. García-Bellido 9 788478 407590 MINISTERIO MINISTERIO DE CIENCIA DE CIENCIA E INNOVACIÓN E INNOVACIÓN ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH Editors: I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and D. García-Bellido Instituto Geológico y Minero de España Madrid, 2008 Serie: CUADERNOS DEL MUSEO GEOMINERO, Nº 9 INTERNATIONAL TRILOBITE CONFERENCE (4. 2008. Toledo) Advances in trilobite research: Fourth International Trilobite Conference, Toledo, June,16-24, 2008 / I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and D. García-Bellido, eds.- Madrid: Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, 2008. 448 pgs; ils; 24 cm .- (Cuadernos del Museo Geominero; 9) ISBN 978-84-7840-759-0 1. Fauna trilobites. 2. Congreso. I. Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, ed. II. Rábano,I., ed. III Gozalo, R., ed. IV. García-Bellido, D., ed. 562 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. References to this volume: It is suggested that either of the following alternatives should be used for future bibliographic references to the whole or part of this volume: Rábano, I., Gozalo, R. and García-Bellido, D. (eds.) 2008. Advances in trilobite research. Cuadernos del Museo Geominero, 9.