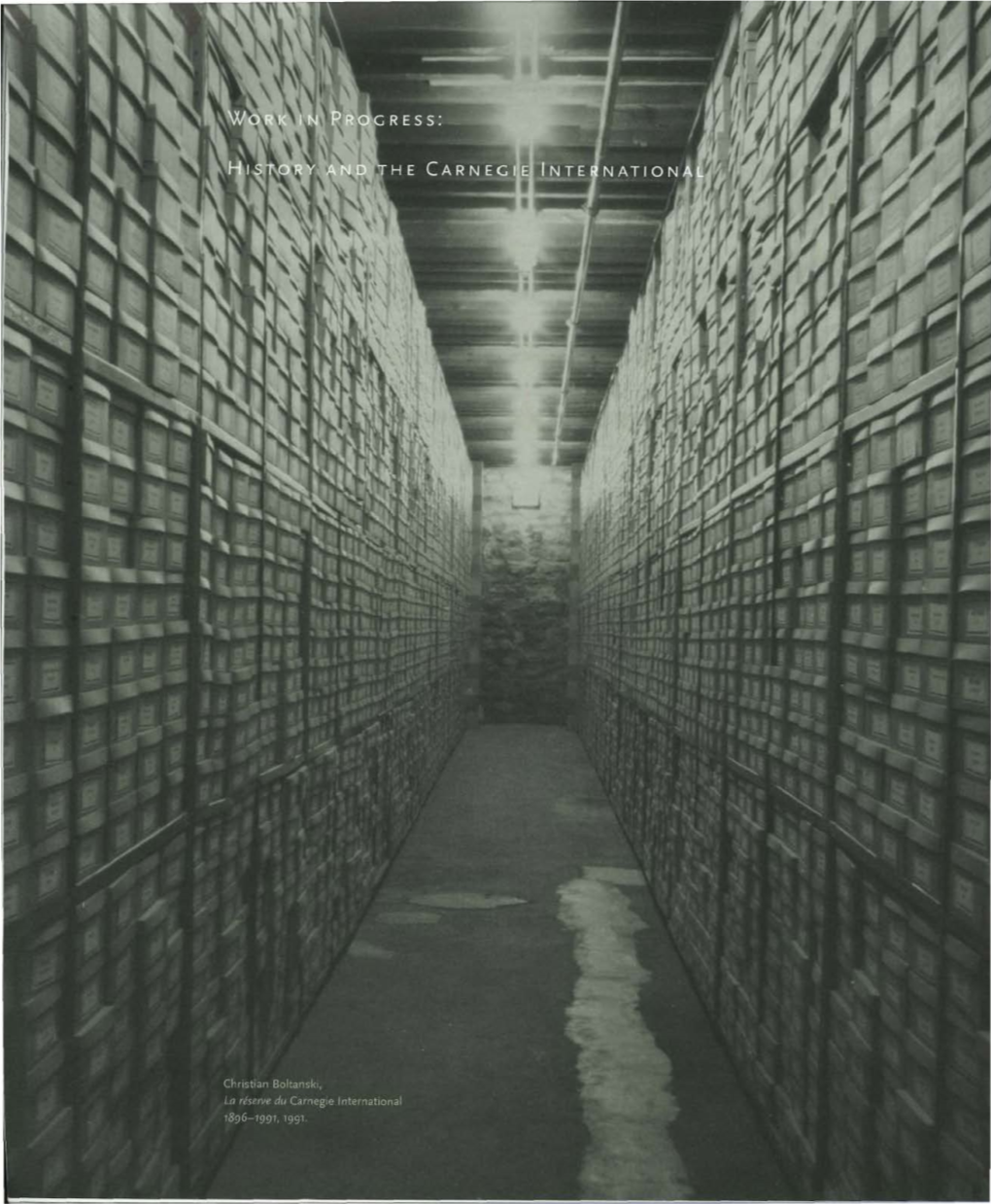

Work in Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carnegie Institute: History, Architecture, Collections

FRICK FINE ARTS LIBRARY The Carnegie Institute: History, Architecture, Collections Library Guide Series, No. 40 “Qui scit ubi scientia sit, ille est proximus habenti.” -- Brunetiere* An Introduction Andrew Carnegie, the founder of The Carnegie Institute, was an American industrialist who worked in the fields of the railroad, oil and became a baron of the iron and steel industries. During his lifetime he donated more than $350 million to a variety of social, educational and cultural causes, the best known of which was his support of the free public library movement. He gave grants for 3,000 library buildings in the English- speaking world between the late 1890s and 1917. The first Carnegie Library opened in 1889 and was built in Braddock, PA near the location of his largest steel mill. The second library opened in Allegheny City during 1890. Carnegie’s most ambitious cultural creation, however, was the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh which included a library, natural history museum, art gallery, and concert hall that were designed by Alden and Harlow between 1891-1907. Few people outside of Pittsburgh know that Andrew Carnegie was also involved in the art world of his day, creating the Art Gallery portion of the Carnegie Institute that is now known as the Carnegie Museum of Art and also beginning what has become one of the oldest international art exhibitions in the world – the Carnegie International in 1896. A little more than a century later the Carnegie Museum of Art had grown to include The Andy Warhol Museum of Art and the Heinz Architectural Center. -

Gagosian Gallery

Artforum January, 2000 GAGOSIAN 1999 Carnegie International Carnegie Museum of Art Katy Siegel When you walk into the lobby of the Carnegie Museum, the program of this year’s International announces itself in microcosm. There in front of you is atmospheric video projection (Diana Thater), a deadpan disquisition on the nature of representation (Gregor Schneider’s replication of his home), a labor-intensive, intricate installation (Suchan Kinoshita), a bluntly phenomenological sculpture (Olafur Eliasson), and flat, icy painting (Alex Katz). Undoubtedly the best part of the show, the lobby is also an archi-tectural site of hesitation, a threshold. Here the installation encapsulates the exhi-bition’s sense of historical suspen-sion, another kind of hesitation. Ours is a time not of endings but of pause. My favorite work, viewed through the museum’s huge glass wall, was the Eliasson, a fountain of steam wafting vertically from an expanse of water on a platform through which trees also rise up. It’s a heart-throbbing romantic landscape. Romantic, but not naive: The work plays on the tradition of the courtyard fountain, and the steam is piped from the museum’s heating system. Combining the natural and the industrial in a way peculiarly appro-priate to Pittsburgh on a quiet Sunday morning in early autumn, it echoed two billows of steam (or, more queasily, smoke?) off in the distance. When blunt physical fact achieves this kind of lyricism, it is something to see. Upstairs in the galleries, Ernesto Neto’s Nude Plasmic, 1999, relies as well on the phenomenology of simple form, but the Brazilian artist avoids Eliasson’s picturesque imagery. -

Letters to Andrew Carnegie ∂

Letters to Andrew Carnegie ∂ A CENTURY OF PURPOSE, PROGRESS, AND HOPE Letters to Andrew Carnegie ∂ A CENTURY OF PURPOSE, PROGRESS, AND HOPE Copyright © 2019 Carnegie Corporation of New York 437 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10022 Letters to Andrew Carnegie ∂ A CENTURY OF PURPOSE, PROGRESS, AND HOPE CARNEGIE CORPORATION OF NEW YORK 2019 CONTENTS vii Preface 1 Introduction 7 Carnegie Hall 1891 13 Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh 1895 19 Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh 1895 27 Carnegie Mellon University 1900 35 Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland 1901 41 Carnegie Institution for Science 1902 49 Carnegie Foundation 1903 | Peace Palace 1913 57 Carnegie Hero Fund Commission 1904 61 Carnegie Dunfermline Trust 1903 | Carnegie Hero Fund Trust 1908 67 Carnegie Rescuers Foundation (Switzerland) 1911 73 Carnegiestiftelsen 1911 77 Fondazione Carnegie per gli Atti di Eroismo 1911 81 Stichting Carnegie Heldenfonds 1911 85 Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching 1905 93 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 1910 99 Carnegie Corporation of New York 1911 109 Carnegie UK Trust 1913 117 Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs 1914 125 TIAA 1918 131 Carnegie Family 135 Acknowledgments PREFACE In 1935, Carnegie Corporation of New York published the Andrew Carnegie Centenary, a compilation of speeches given by the leaders of Carnegie institutions, family, and close associates on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Andrew Carnegie’s birth. Among the many notable contributors in that first volume were Mrs. Louise Carnegie; Nicholas Murray Butler, president of both the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and Columbia University; and Walter Damrosch, the conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra whose vision inspired the building of Carnegie Hall. -

2 0 0 3 D O N O

CELEBRATING 2003 DONORS AND VOLUNTEER LEADERSHIP PHOTO: TERRY CLARK Dolly Ellenberg, (left) Vice President, Development; Trustee Lee Foster; and Suzy Broadhurst, Chair, Board of Trustees and Interim President 44 CARNEGIE • MAY/JUNE • 2004 AT CARNEGIE MUSEUMS OF PITTSBURGH, WE HAVE AN IN 2003, CARNEGIE MUSEUMS OF PITTSBURGH ENJOYED A AMAZING LEGACY OF GIVING. From our staff, to our volunteer DYNAMIC AND FRUITFUL YEAR: the Museum of Art reopened the leaders, to our constantly growing base of donors, we need not Scaife Galleries after 18 months of extensive renovations; The Andy look any farther than our own family of supporters to see what Warhol Museum celebrated Andy Warhol’s 75th birthday with true community stewardship is all about. exhibitions and events that drew celebrities and visitors from around the world; Carnegie Science Center received one of the nation’s Of course, we’re all descendants of the ultimate Carnegie highest awards for the innovative educational and outreach programs Museums’ donor and volunteer leader—Andrew Carnegie. He set the it provides; the Museum of Natural History effectively executed bar incredibly high. But I believe he knew that the institution he DinoMite Days, the largest and most popular public art exhibit the created would continue to inspire others the way it had inspired region has ever enjoyed; and, Carnegie Museums once again exceeded him. And, like him, other individuals would do extraordinary the previous year’s level of charitable giving by almost $2 million. things to support and grow it. All of these accomplishments—and many more—were made possible One of those people is Lee Foster. -

TRISHA DONNELLY Born 1974, San Francisco, CA Lives

TRISHA DONNELLY Born 1974, San Francisco, CA Lives and works in New York, NY EDUCATION 2000 MFA, Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT 1995 BFA, University of California, Los Angeles, CA AWARDS 2017 Wolfgang Hahn Prize, Museum Ludwig, Cologne 2012 Faber-Castell Prize, Nuremberg 2011 Finalist for Hugo Boss Prize, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, NY Sharjah Biennial 10 Primary Prize, 10th Sharjah Biennial, United Arab Emirates 2010 Luma Foundation Prize, Rencontres d’Arles, Arles 2004 CENTRAL Art Prize, awarded by Kölnischer Kunstverein and the Central Health Insurance Company, Germany SOLO EXHIBITIONS (*publication/catalogue) 2017 Wolfgang Hahn Prize, Museum Ludwig, Cologne 2016 Serralves Villa, Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art, Porto 2015 Matthew Marks Gallery, Los Angeles, CA Air de Paris, Paris Number Ten: Trisha Donnelly, Julia Stoschek Collection, Dusseldorf 2014 Serpentine Gallery, London 2013 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich 2011 Trisha Donnelly: Recipient of 2010 LUMA Award, Villa des Alyscamps, Aries, (curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Beatrix Ruf) 2010 Air de Paris, Paris Casey Kaplan, New York, NY Portikus, Frankfurt Am Main Center for Contemporary Art, CCC Kitakyushu, Kitakyushu 2009 Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna (MAMbo), Bologna 2008 Eva Presenhuber, Zurich Centre d’édition Contemporain, Bâtiment d’art Contemporain, Geneva Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA Renaissance Society, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL The Douglas -

Diana Thater Born 1962 in San Francisco

This document was updated November 25, 2020. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Diana Thater Born 1962 in San Francisco. Lives and works in Los Angeles. EDUCATION 1990 M.F.A., Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California 1984 B.A., Art History, New York University SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Diana Thater: Yes there will be singing, David Zwirner Offsite/Online: Los Angeles [online presentation] 2018 Diana Thater, The Watershed, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston 2017-2019 Diana Thater: A Runaway World, The Mistake Room, Los Angeles [itinerary: Borusan Contemporary, Istanbul; Guggenheim Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain] 2017 Diana Thater: The Starry Messenger, Moody Center for the Arts at Rice University, Houston, Texas 2016 Diana Thater, 1301PE, Los Angeles 2015 Beta Space: Diana Thater, San Jose Museum of Art, California Diana Thater: gorillagorillagorilla, Aspen Art Museum, Colorado Diana Thater: Life is a Timed-Based Medium, Hauser & Wirth, London Diana Thater: Science, Fiction, David Zwirner, New York Diana Thater: The Starry Messenger, Galerie Éric Hussenot, Paris Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination, Los Angeles County Museum of Art [itinerary: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago] [catalogue] 2014 Diana Thater: Delphine, Saint-Philibert, Dijon [organized by Fonds régional d’art contemporain Bourgogne, Dijon] 2012 Diana Thater: Chernobyl, David Zwirner, New York Diana Thater: Oo Fifi - Part I and Part II, 1310PE, Los Angeles 2011 Diana Thater: Chernobyl, Hauser & -

Welcome to Pittsburgh's Arts Community!

Welcome to Pittsburgh’s Arts Community! Welcome to the ‘burgh! As you are soon to discover, Pittsburgh is a vibrant cultural city with unique rust belt roots, and a deep-rooted love of all things black & gold. Navigating Pittsburgh’s myriad cul- tural institutions and social networks can be overwhelming, but we hope this guide will demystify much of it as we im- part our insider knowledge. Pittsburgh Emerging Arts Lead- ers (PEAL) seeks to serve and support local emerging arts leaders by connecting them with resources, networking and professional development opportunities. We are a steering committee of emerging arts leaders like yourself, so don’t hesitate to reach out to us if we can be of any help. We hope that you will join us at a PEAL event soon. Best, Katie Conaway PEAL Chair http://twitter.com/pgheal https://www.facebook.com/PghEAL Who is peal? Pittsburgh Emerging Arts Leaders (PEAL) exists to provide networking, resources and professional development opportunities to emerging arts managers in Pittsburgh. We are an entirely volun- teer-run organization, supported by the leadership of the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council. PEAL produces a number of signature events including Fireside Chats, Mastermind, Coffee With, and Happy Hours. PEAL also maintains an active digital presence through our Facebook and Twitter pages. We distribute a monthly email newsletter featuring all of our events, as well as regional job postings, events of interest to the PEAL community, and special topics. Be sure to sign-up here. How to Use this handbook This is an orientation of the Pittsburgh Arts Community that is meant to help you navigate through the city’s arts venues, organizations and major events. -

The University and the Community Carnegie Mellon and Its Relationship to Pittsburgh 1900-2008

The University and the Community Carnegie Mellon and its Relationship to Pittsburgh 1900-2008 Jess Anders, Liz DeVleming, Vincent Giacalone, Evan Gross, Zhi Wei Leong, Ross MacConnell, Ellen Parkhurst, & Faryal Kahn Instructor: Professor Joel A. Tarr Course Assistants: Alex Bennett, James Dougherty 79-410 | Fall 2008 Table of Contents ACKOWLEDGEMENTS 3 INTRODUCTION 6 THE DEVELOPMENT OF A UNIVERSITY 7 THE WOMEN OF CARNEGIE 27 WORK, PRAY, GIVE 48 THE HISTORY OF CARNEGIE ATHLETICS 66 CARNEGIE MELLON AND THE PITTSBURGH PUBLIC SCHOOLS 108 TECHNOLOGY 140 ACCOMMODATING CHANGE 157 FINE ARTS AND THE COMMUNITY ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. Appendix: Some Notes on Environmental Research This Report is dedicated to Dr. Edwin Fenton Professor Emeritus, Carnegie Mellon University For his Contributions Towards Strengthening the Relationship Between Carnegie Mellon University and the Pittsburgh Community 4 79-410 Fall 2008 Acknowledgements We would like to particularly acknowledge the help of the following University faculty and staff members who visited our class and shared their perspectives about the relationship of CMU to the community in areas of their expertise. In addition, they generously provided direction concerning various resources that would aid our study. We would also like to acknowledge the generosity of a number of individuals from both inside and outside the University who shared their various expertise in different areas with us. The names of these individuals are listed in the reference notes for each of the sections. Jennie M. Benford, -

Christopher / Cristóbal Martínez

Christopher / Cristóbal Martínez Art and Technology Program | San Francisco Art Institute 800 Chestnut St., San Francisco, CA 94133 Email: [email protected] Education May 2015 Ph.D., Rhetoric/Composition/Linguistics, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ May 2011 M.A., Media Arts and Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ Dec 2002 B.F.A., Painting, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ Dec 2002 B.A., Studio Art, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ Doctoral Dissertation May 2015 Tecno-Sovereignty: An Indigenous Theory and Praxis of Media Articulated Through Art, Technology, and Learning Academic Appointments 2018 – Current Art and Technology Program Chair, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA 2020 – Current Associate Professor of Art and Technology, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA 2018 – 2020 Assistant Professor of Art and Technology, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA 2017 – 2018 Distinguished Visiting Faculty, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA 2016 – 2017 Postdoctoral Fellow: Indigenous Art, Digital Design, and Education, Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts | Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 2010 – 2013 Instructor, School of Transborder Studies, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ Professional Appointments 1997 - 2008 Environmental Graphic Designer, Office of the University Architect, Facilities Management, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ Christopher / Cristóbal Martínez Curriculum Vitae 2 Artist Appointments 2018 – Current Artist, Red -

2013 Carnegie International Opening Weekend

Carnegie Museum of Art Black-tie dinner in Carnegie Museum of Art Music Hall foyer, 1928 2013 Carnegie International opening weekend October 4–6, 2013 www.carnegieinternational.org/opening 2013 Carnegie International As installation continues for perhaps the most important exhibition of new international art in the US; as we engage with artists Ei Arakawa/Henning Bohl, Phyllida Barlow, Yael Bartana, Sadie Benning, Bidoun Library, Nicole Eisenman, Lara Favaretto, Vincent Fecteau, Rodney Graham, Guo Fengyi, Wade Guyton, Rokni Haerizadeh, He An, Amar Kanwar, Dinh Q. Lê, Mark Leckey, Pierre Leguillon, Sarah Lucas, Tobias Madison, Zanele Muholi, Paulina Olowska, Pedro Reyes, Kamran Shirdel, Gabriel Sierra, Taryn Simon, Frances Stark, Joel Sternfeld, Mladen Stilinović, Zoe Strauss, Henry Taylor, Tezuka Architects, Transformazium, Erika Verzutti, and Joseph Yoakum; as we realize spectacular new commissions testing the limits of the institution; as we open a playground in front of the museum; as we reopen The Playground Project, which inspired art and architecture summer camps; as we install the archive documenting the exceptional history of the Carnegie International (est. 1896); as Zoe Strauss is installing her photo studio in Homestead and Transformazium is building the Art Lending Collection at Braddock Carnegie Library; as we plan artist talks, performances, and lectures; we announce the program of the Opening Weekend for the 2013 Carnegie International. Performances, parties, and spectacular new commissions—the opening weekend of the 2013 Carnegie International celebrates the work of 35 of the most important artists today, and the world-class collection assembled through 117 years of International exhibitions. Welcome to Pittsburgh, the city of the Carnegie International! Daniel Baumann, Dan Byers, Tina Kukielski Friday, October 4 Press preview 9:30am–2:30pm Members of the press may apply for accreditation here. -

Paul Chan 1973 Born in Hong Kong 1996 Art Institute of Chicago School

Paul Chan 1973 Born in Hong Kong 1996 Art Institute of Chicago School. B.F.A., Video/Digital Arts. 2002 Bard College. MFA, Film/Video/New Media. Solo Exhibitions 2008 Greene Naftali, New York New Museum, New York, NY 2007 Serpentine Gallery, London Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam Greene Naftali Gallery, New York, NY Western Front, Vancouver, Canada 2006 Magasin 3, Stockholm, Sweden Portikus, Frankfurt, Germany Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, PA, curated by Chrissie Iles Para/Site Art Space, Hong Kong Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, TX (catalogue) Galleria Massimo De Carlo, Milan, Italy 2005 UCLA Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA Tin Drum Trilogy, Franklin Art Works, Minneapolis, MN Tin Drum Trilogy, Hallwalls, Buffalo, NY 2004 Greene Naftali Gallery, New York, NY 2003 MOMA Film at the Gramercy Theater, New York, NY Group Exhibitions 2007 Herhistory, Nik.P.Goulandris Foundation-Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens Paper Trail: A Decade in Acquisitions, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis Art in America: 300 Years of Innovation, National Art Museum Museum of China, Beijing; Shanghai Museum, Shanghai; Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art, Shanghai Still Life, Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, curated by Dodie Kazanjian New Frontier, Sundance Film Festival, Park City, UT 2006 Empathetic, Temple Gallery at the Tyler School of Art, Philadelphia, PA The Un-Homely (Phantoms Scenes in Global Society), 2nd International Biennial of Contemporary Art of Seville, Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporaneo, Seville Belief and -

Madeleine Grynsztejn Oral History Transcript

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Regional Oral History Office 75th Anniversary The Bancroft Library Oral History Project University of California, Berkeley SFMOMA 75th Anniversary MADELEINE GRYNSZTEJN SFMOMA Staff, 2000-2008 Elise S. Haas Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture Interview conducted by Lisa Rubens and Richard Cándida Smith in 2008 Copyright © 2009 by San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Funding for the Oral History Project provided in part by Koret Foundation. ii Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Madeleine Grynsztejn, dated July 6, 2009. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes.