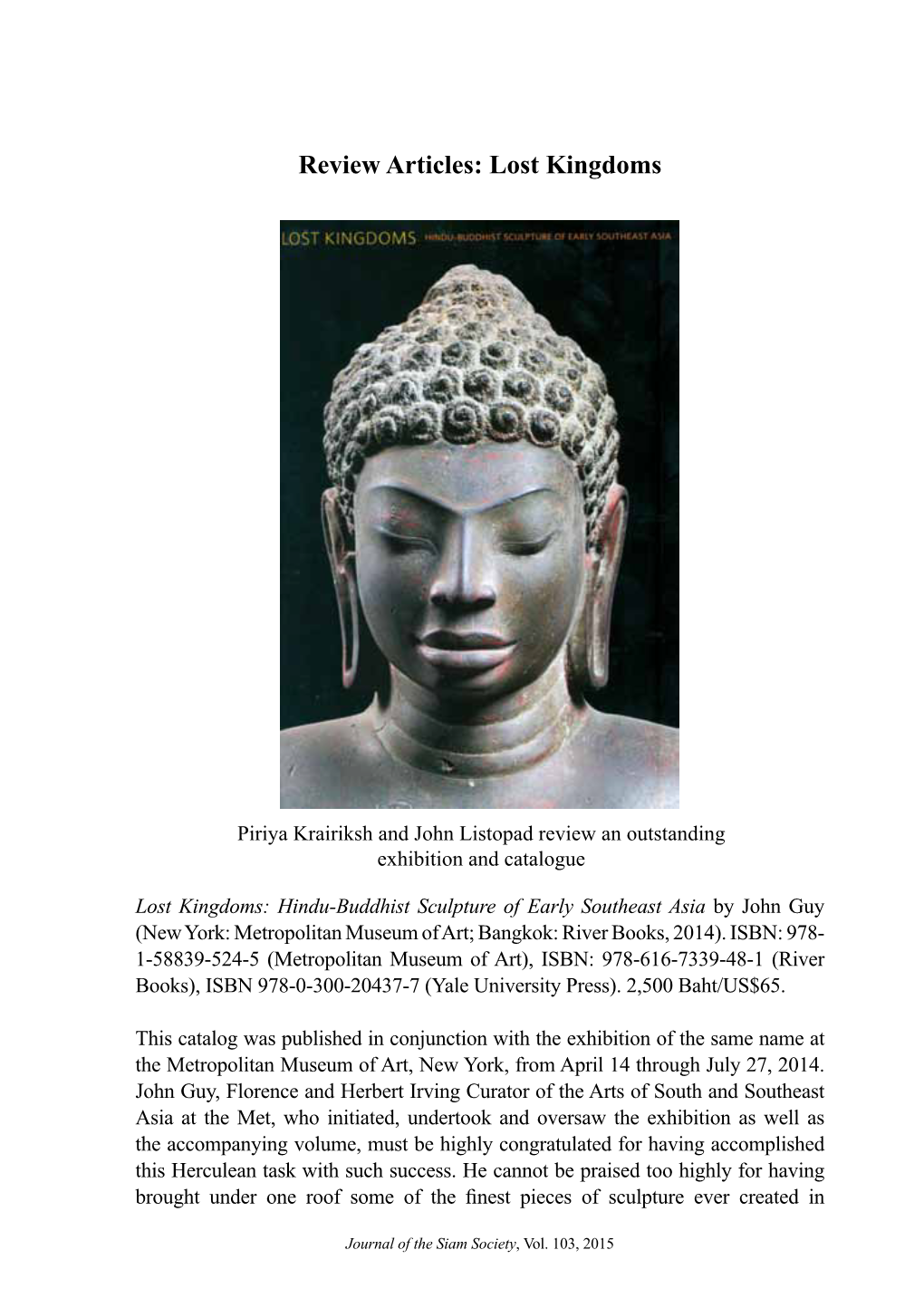

Review Articles: Lost Kingdoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanistic Elements in Early Buddhism and the "Theravada Tradition"

Humanistic Elements in Early Buddhism and the "Theravada Tradition" By Ananda W. P. Guruge ABSTRACT The paper begins with an examination of the different defuritions of humanism. Humanism primarily consistsof a concern with interests andideals of human beings, a way of peefection of human personality, a philosophical attitude which places the human and human val.Mes above all others, and a pragmatic system (e.g. that of F. C. S. Schiller and William James) whichdiscounts abstract theorizing and concentrates on the knowable and the doable. EarlyBuddhism, by whichis meant the teachingsof the Buddha as found in the PallCanon and the AgamaSutras, isdistinguished from other tradifions. The paperclarifies the error of equating Early Buddhism with the so-called Theravada Tradition of South and SoutheastAsia. Historically, the independent Theravada Tradifion with whatever specificity it had in doctrines came to an end when the three Buddhist schools (Mahavihara, Abhayagiri andJetavana) of SriLanka were unifiedin the twelfth century. What developed since then and spread to South andSoutheast Asia is an amalgam of allBuddhist traditions with the Pall Canon andits commentaries as the scriptures. With the reform measures in the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries, the kind of modern Buddhism prevalent as "Theravada" is flexible, tolerant and reinforced by modernizing influence of Western Christian values. The paper analyses references to the Buddha's own autobiographical statements and other data in the Pali Canon and Commentaries and shows that the Buddha stood as a man before human beings to demonstrate how they could develop themselves by their own effort and reach the end of suffering. This final goal of peefedion is within the reach of every human being. -

Visit the World's Largest Roadside Attr

VISIT THE WORLD’S LARGEST ROADSIDE ATTRACTIONS! by Marcia Amidon Lusted ne of the fun parts of any road trip is finding Ostrange and interesting things to stop and see along the way. All over the world, roadside attractions Sure, just set that can be the biggest, the funniest, or the strangest down anywhere. objects you’ve ever seen. Fasten your seat belts as we take you on a tour of some of them. The Headington Shark, Oxford, United Kingdom While traveling around the world, you might want to visit the Headington Shark. He’s not in an aquarium: this shark is actually sticking into the roof of a house. The house was a basic terraced house on a normal street until 1986, when its owner decided to liven it up. He asked a sculptor friend to create a 25-foot fiberglass shark that would sit on the roof as if it had just crashed there. The owner later said that the shark was put there to protest things like nuclear power and weapons and government incompetence, but he also said he just liked sharks. Tourists from all over the world visit and local The Great Buddha of Thailand residents are proud of it. If you find yourself in Thailand, visit the Great Buddha, also called the Big Buddha, found at the Wat Muang temple in Ang Thong Province. This giant buddha, seated in a position called Maravijaya Attitude, is made of concrete painted gold. He towers 300 feet (92 meters) high and is 210 feet (63 meters) wide, and sits on the roof of the temple building. -

Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors

About the Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors The transformation of transport corridors into economic corridors has been at the center of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Economic Cooperation Program since 1998. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) conducted this Assessment to guide future investments and provide benchmarks for improving the GMS economic corridors. This Assessment reviews the state of the GMS economic corridors, focusing on transport infrastructure, particularly road transport, cross-border transport and trade, and economic potential. This assessment consists of six country reports and an integrative report initially presented in June 2018 at the GMS Subregional Transport Forum. About the Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Cooperation Program The GMS consists of Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, the People’s Republic of China (specifically Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), Thailand, and Viet Nam. In 1992, with assistance from the Asian Development Bank and building on their shared histories and cultures, the six countries of the GMS launched the GMS Program, a program of subregional economic cooperation. The program’s nine priority sectors are agriculture, energy, environment, human resource development, investment, telecommunications, tourism, transport infrastructure, and transport and trade facilitation. About the Asian Development Bank ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining -

JUNE to JULY 2018 ESE Current Issues

*/5&3/"5*0/"- :0("%": +6/& " Ŋ! " &!! $""& " Őm;ƑƏƐѶŊѴƑƏƐѶő :K56D2325ά56>:;ά3:AB2>άBG@6ά3:G32@6EI2Dά>G4=@AIάB2F@2ά36@82>GDGά4:6@@2;άH;<2K2I252άH;L28άF;DGB2F:;ά=G=2FB2>>Kά=A>=2F2 Website : www. aceengineeringpublications.com ACE Engineering Publications (A Sister Concern of ACE Engineering Academy, Hyderabad) Hyderabad | Delhi | Bhopal | Pune | Bhubaneswar | Bengaluru | Lucknow | Patna | Chennai | Vijayawada | Visakhapatnam | Tirupati | Kukatpally | Kolkata ESE (Prelims) Current Issues (June and July 2018) On Economic & Industrial Development Issues on Social Development International Issues Environment Science & Technology Miscellaneous ACE is the leading institute for coaching in ESE, GATE & PSUs H O: Sree Sindhi Guru Sangat Sabha Association, # 4-1-1236/1/A, King Koti, Abids, Hyderabad-500001. Ph: 040-23234418 / 19 / 20 / 21, 040 - 24750437 7 All India 1st Ranks in ESE 43 All India 1st Ranks in GATE Foreword Current Issues for ESE Dear Students, This book is intended to help students, prepare current affairs on a monthly basis. The topics covered give a comprehensive understanding on issues related to Socio, Economic, Industrial Development, Energy and Environment and ICT based tools. Apart from technical knowledge, current affairs help an aspirant to understand issues in a multi- dimensional approach and contributes to a holistic personality development. The coverage of news and events given are the most pertinent for ESE Revised pattern. The key to master current affairs is a ‘piece-meal preparation’ over a period of time and this material is an endeavor to help students prepare in a systematic manner. This issue covers Current Affairs from June and July 2018 and subsequent issues will be given on a bi-monthly basis. -

Ormation of the Sangha 9

top home ALL From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 1. Gautama Buddha 2. Traditional biographies / Primary biographical sources 3. Nature of traditional depictions 4. Biography Conception and birth 5. Early life and marriage 6. Departure and ascetic life 7. Enlightenment 8. Formation of the sangha 9. Travels and teaching 10. Assassination attempts 11. Mahaparinirvana 12. Physical characteristics 13. Teachings 14. Other religions 15. Buddhism 16. Life of the Buddha 17. Buddhist concepts 18. Life and the World 19. Suffering's causes and solution - The Four Noble Truths / Noble Eightfold Path 20. The Four Immeasurables 21. Middle Way 22. Nature of existence 23. Dependent arising 24. Emptiness 25. Nirvana 26. Buddha eras 27. Devotion 28. Buddhist ethics 29. Ten Precepts 30. Monastic life 31. Samādhi (meditative cultivation): samatha meditation 32. In Theravada 33. Praj๑ā (Wisdom): vipassana meditation 34. Zen 35. History 36. Indian Buddhism, Pre-sectarian Buddhism, Early Buddhist schools, Early Mahayana Buddhism, Late Mahayana Buddhism, Vajrayana (Esoteric Buddhism) 37. Development of Buddhism 38. Buddhism today 39. Demographics 40. Schools and traditions 41. Timeline 42. Theravada school 43. Mahayana traditions 44. Bodhisattvas, Vajrayana tradition 45. Buddhist texts, Pāli Tipitaka 46. Mahayana sutras 47. Comparative studies 48. History 49. Lineage of nuns 50. Modern developments 51. Overview of Philosophy 52. Fundamentals of Theravada, Cause and Effect, The Four Noble Truths, The Three Characteristics, The Three Noble Disciplines 53. Meditation 54. Scriptures 55. Lay and monastic life, Ordination, Lay devote 56. Monastic practices 57. Influences 58. Monastic orders within Theravada 59. Noble Eightfold Path 60. Dependent Origination 61. The Twelve Nidanas 62. Three lives 63. -

DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOKLET UNTIL YOU COMPLETE the TEST ANSWER BOOKLET GENERAL STUDIES PAPER-I Free Mock Test-1

1 DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOKLET UNTIL YOU COMPLETE THE TEST ANSWER BOOKLET GENERAL STUDIES PAPER-I Free Mock Test-1 Answer Key 1. A 35. B 69. A 2. C 36. A 70. D 3. B 37. B 71. D 4. D 38. B 72. A 5. D 39. C 73. D 6. B 40. B 74. B 7. C 41. A 75. C 8. B 42. A 76. B 9. D 43. D 77. A 10. D 44. A 78. D 11. B 45. C 79. B 12. D 46. B 80. A 13. A 47. A 81. A 14. A 48. C 82. A 15. A 49. C 83. A 16. B 50. A 84. B 17. B 51. A 85. A 18. D 52. B 86. B 19. A 53. D 87. C 20. D 54. C 88. D 21. D 55. D 89. A 22. A 56. C 90. C 23. A 57. C 91. B 24. C 58. C 92. C 25. D 59. D 93. D 26. B 60. A 94. D 27. C 61. A 95. B 28. B 62. A 96. C 29. A 63. B 97. B 30. D 64. A 98. A 31. C 65. C 99. A 32. A 66. B 100. B 33. D 67. D 34. C 68. A OBJECTIVE IAS www.objectiveias.in OAS Prelims-2020 OBJECTIVE IAS 2 Q1. Implicit Cost: An implicit cost is proportion with production output. any cost that has already occurred but Variable costs increase or decrease is not necessarily shown or reported as depending on a company’s production a separate expense. -

Fte1^^ Lltrerar^

THE IMPACT OF SOME HA HA YANA CONCEPTS ON SINHALESE BUDDHISM Wisid>'Spet>i^4r'-fte1^^ Lltrerar^ Soirrees up to t-hc FifiHtsTitli Century By Sangapala Arachchige Hemalatha Goonatilake Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of London ProQuest Number: 11010415 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010415 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Abstract This study attempts to examine the influence of some specific Mahayana concepts on Sinhalese Buddhism. The first chapter serves as a historical backdrop to the inflow of various non-orthodox movements into Ceylon and records the continuous impact of the Maha yana on the Theravada from the earliest times. The second chapter deals with the development of the con cept of the threefold bodhi and examines in some detail the way in which the goal of Ceylon Buddhism shifted from the Theravada arahantship to the Mahayana ideal of Buddhahood. Furthermore it suggests that this new ideal was virtually absorbed into Ceylon Buddhism. The next chapter discusses the Mahayana doctrines of trlkaya, vajrakaya . -

Insights Pt 2019 Exclusive (Art and Culture)

INSIGHTS PT 2019 EXCLUSIVE (ART AND CULTURE) Table of Contents FESTIVALS / CELEBRATIONS ..................................................................................................... 5 1. Indian Harvest Festivals ...................................................................................................................... 5 2. Makaravilakku Festival ....................................................................................................................... 5 3. Hornbill Festival 2018 ......................................................................................................................... 5 4. Dwijing Festival................................................................................................................................... 6 5. Kambala ............................................................................................................................................. 6 6. SANGAI TOURISM FESTIVAL ................................................................................................................ 6 7. India International Cherry Blossom Festival ......................................................................................... 7 8. Behdienkhlam Festival ........................................................................................................................ 7 9. Ambubachi Mela................................................................................................................................. 8 10. Rashtriya Sanskriti Mahotsav-2018 -

Buddhist Diplomacy: History and Status Quo

BUDDHIST DIPLOMACY: HISTORY AND STATUS QUO Juyan Zhang, Ph.D. September 2012 Figueroa Press Los Angeles BUDDHIST DIPLOMACY: HISTORY AND STATUS QUO Juyan Zhang Published by FIGUEROA PRESS 840 Childs Way, 3rd Floor Los Angeles, CA 90089 Phone: (213) 743-4800 Fax: (213) 743-4804 www.figueroapress.com Figueroa Press is a division of the USC Bookstore Copyright © 2012 all rights reserved Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the author, care of Figueroa Press. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, neither the author nor Figueroa nor the USC Bookstore shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by any text contained in this book. Figueroa Press and the USC Bookstore are trademarks of the University of Southern California ISBN 13: 978-0-18-214385-6 ISBN 10: 0-18-214385-6 For general inquiries or to request additional copies of this paper please contact: USC Center on Public Diplomacy at the Annenberg School University of Southern California 3502 Watt Way, G4 Los Angeles, CA 90089-0281 Tel: (213) 821-2078; Fax: (213) 821-0774 [email protected] www.uscpublicdiplomacy.org CPD Perspectives on Public Diplomacy CPD Perspectives is a periodic publication by the USC Center on Public Diplomacy, and highlights scholarship intended to stimulate critical thinking about the study and practice of public diplomacy. -

Paths to Perfection Buddhist Art at the Freer|Sackler Paths to Perfection, Buddhist Art at the Freer|Sackler, © 2017, Smithsonian Institution

Paths to Perfection buddhist art at the freer|sackler Paths to Perfection, Buddhist Art at the Freer|Sackler, © 2017, Smithsonian Institution. All rights reserved. Published by Freer|Sackler, the Smithsonian’s museums of Asian art: asia.si.edu Distributed in the USA and Canada by Consortium Book Sales & Distribution The Keg House 34 Thirteenth Avenue, NE, Suite 101 Minneapolis, MN 55413-1007 USA www.cbsd.com GILES An imprint of D Giles Limited 4 Crescent Stables 139 Upper Richmond Road London SW15 2TN UK www.gilesltd.com Page II: North wall, Lianhuadong, Longmen cave temples; China, Henan Province, 1910; Charles Lang Freer Papers; Freer|Sackler Archives, FSA A.01 12.05.GN.150 Editor: Joelle Seligson Content editor: Debra Diamond Designer: Adina Brosnan McGee Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Freer Gallery of Art, author. | Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (Smithsonian Institution), author. Title: Paths to perfection : Buddhist art at the Freer|Sackler. Description: Washington, D.C. : Freer|Sackler, the Smithsonian’s museum of Asian art ; London : Giles, [2017] | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017013603 | ISBN 9781907804649 (pbk.) Subjects: LCSH: Freer Gallery of Art--Guidebooks. | Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (Smithsonian Institution)--Guidebooks. | Buddhist art--Guidebooks. | Art--Washington (D.C.)--Guidebooks. Classification: LCC N8193.A2 F74 2017 | DDC 709.753--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017013603 Typeset in Benton Sans Printed and bound in Slovenia. 1 Introduction In the history of world art, few figures are as familiar or widely depicted as the Buddha. For thousands of years, artists have shaped his image in metal and stone and painted his form on the walls of monasteries, temples, and caves. -

Top 10 Tallest Statues in the World - GK Notes for SSC & Banking!

Top 10 Tallest Statues in the World - GK Notes for SSC & Banking! With the Statue of Unity unveiled on 31st October 2018, India has made its way to the top of the list of tallest statues in the world. The Statue of Unity which is 182 meters tall, overtook the previous record holder, the 153 meters Spring Temple Buddha, in China’s Lushan County. Read this article to know about the Tallest Statues in the World. Here is a list of the top 10 tallest statues in the world. Rank Statue Height Country 1 Statue of Unity 182 m India 2 Spring Temple Buddha 153 m China 3 Laykyun Setkyar 116 m Myanmar 4 Ushiku Daibutsu 11o Japan 5 Sendai Daikannon 100 Japan 6 Qianshou Qianyan Guanyin of Weishan 99 m China 7 Great Buddha of Thailand 92 m Thailand 8 Dai Kannon of Kita no Miyako park 88 m Japan 9 Rodina-Mat' Zovyot! (The Motherland Calls) 85 m Russia 10 Awaji Kannon 80 m Japan Tallest Statues in the World 1 | P a g e 1. Statue of Unity, India The Statue of Unity in India, at 182 meters is the tallest statue in the world. It was a tribute to one of the founding fathers and the first Home Minister of India Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel on his birth anniversary on 31st October 2018. The building of this statue costed Rs. 2,989 crore. It took approximately 42 months to be built. 3,400 labourers and 250 engineers were required to complete this project. 2. Spring Temple Buddha, China In the second place is the Spring Buddha Temple statue, which measures 153 meters tall. -

CULTURE Table of Contents 1

CULTURE Table of Contents 1. DANCES & MUSIC __________________ 2 7.2. Paika Rebellion ___________________ 17 1.1. Folk & Tribal Dance _________________ 2 7.3. Sadharan Brahmo Samaj ____________ 18 1.2. India’s First Music Museum __________ 2 7.4. Battle of Haifa ____________________ 18 1.3. Ghumot: Goa’s Heritage Instrument ___ 3 7.5. Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms _______ 19 2. PAINTINGS & OTHER ART FORMS ______ 4 7.6. Azad Hind Government _____________ 19 2.1. Thanjavur Paintings _________________ 4 8. PERSONALITIES ___________________ 21 2.2. Mithila Painting ____________________ 4 8.1. Guru Nanak Dev Ji _________________ 21 2.3. Bagru Block Printing ________________ 4 8.2. Saint Kabir _______________________ 21 2.4. Aipan ____________________________ 5 8.3. Swami Vivekananda _______________ 22 2.5. Tholu Bommalata __________________ 5 8.4. Sri Satguru Ram Singhji _____________ 23 3. SCULPTURE AND ARCHITECTURE ______ 6 8.5. Statue of Ramanujacharya __________ 23 3.1. Konark Sun Temple _________________ 6 8.6. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel ____________ 24 3.2. Khajuraho Temples _________________ 6 8.7. Sir Chhotu Ram ___________________ 24 3.3. Sanchi Stupa ______________________ 6 8.8. Tribal Freedom Fighters ____________ 25 3.4. Badshahi Ashoorkhana ______________ 7 9. ANCIENT HISTORY _________________ 26 3.5. India’s National War Memorial _______ 7 9.1. Vakataka Dynasty _________________ 26 3.6. Monuments of National Importance ___ 8 9.2. Couple’s Grave in Harappan Settlement 26 3.7. World Capital of Architecture _________ 8 10. GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES/SCHEMES & 3.8. My Son Temple Complex ____________ 9 INSTITUTIONS ______________________ 27 4. LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE _______ 10 10.1.