Author Available from Journal Cit Edrs Price

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mm2 Asia ADD (No Change)

Company Note Media - Integrated │ Singapore │ October 8, 2019 Insert Insert Singapore mm2 Asia ADD (no change) Consensus ratings*: Buy 2 Hold 1 Sell 0 Set for the bigger stage Current price: S$0.22 ■ We like mm2 as an integrated media play, with 15.0% FY20-22F PATMI Target price: S$0.32 CAGR underpinned by robust Unusual pipeline and cinema turnaround. Previous target: S$0.37 ■ Replication of More than Blue’s success is a potential catalyst for the stock; Up/downside: 43.5% its China box office also contributed to higher receivables in 1QFY20. CGS-CIMB / Consensus: 28.9% ■ Possible stake monetisation could lower net gearing and finance expenses Reuters: MM2A.SI by S$1.2m-6.0m. We expect share price re-rating to follow. Maintain Add. Bloomberg: MM2 SP Market cap: US$185.3m S$255.8m Expect earnings growth to return from 2QFY3/20F Average daily turnover: US$0.15m Our recent conversation with management reaffirmed our view that earnings growth will S$0.21m resume from 2Q20F after a lacklustre 1Q20 (PATMI -4.1% yoy), on a stronger pipeline by Current shares o/s: 1,163m Unusual and post-production work. These, coupled with enhanced profitability of the Free float: 36.4% cinema operations and more moderated growth in production budget, underpin our FY20- *Source: Bloomberg 22F topline and PATMI CAGR of 7.8% and 15.0%, respectively. At 12.3x FY20F P/E (1 s.d. below historical mean and 60% lower than sector average), we think the tapering Key changes in this note growth has been more than priced in and see potential upside from current level. -

Summerwhatsonbooklet.Pdf

Introduction Hello! Everybody lift your faces to the sun and enjoy the long, hot, lazy days of summer 2019 (we hope!) There’s a new weekly section at the beginning of Sutton Coldfield’s annual music competition this summer guide, highlighting just what happens and throughout the month of July, with local every single day of the week in Sutton Coldfield. acts joining us to celebrate our third ‘Month of There really is something for everyone! Music’ (highlighted in this guide in pink). Plus, the As well as great selection of beers and town centre once again hosts acts from the 35th ciders to be had at beer festivals run by several Birmingham, Sandwell and Westside Jazz Festival, of Sutton’s pubs; fun, laughter and sporting bringing a wonderful swing to your shopping prowess is to be found in abundance once stride in July. So grab a deck-chair and come again at the much-loved Community Games. and join the summer buzz! Local musical talent will be on display again at 2 Weekly Events Mondays Cost: Come and have a go for free. Thereafter £3 per session or join for the season (£50). Artability 10am – 12 midday Speed Quizzing Sutton Coldfield Baptist Church, Trinity Hill, 8pm Sutton Coldfield B72 1TA The Brewhouse and Kitchen, 8 Birmingham Road, Artability is for anyone who like painting, drawing, Sutton Coldfield B72 1QD sewing, craftwork, making jewellery and anything Put your thinking caps on and pick your smartest crafty! Meet in the Church Hall. (or flukiest) friends to join us for our weekly speed Cost: £2 donation to cover costs. -

July 2019 up and Down the Country That Need Your Support

Issue 93 July2019 FREE SLAP Supporting Local Arts & Performers WORCESTER’S NEW INDEPENDENT ITALIAN RESTAURANT Traditional Italian food, cooked the Italian way! We create all dishes in our kitchen, using only the finest quality fresh ingredients. f. t. i. SUGO at The Lamb & Flag SUGO at Friar St 30 The Tything 19-21 Friar Street, Worcester Worcester WR1 1JL WR1 2NA 01905 729415 01905 612211 [email protected] [email protected] It’s another bumper month here in Slapland with so much to look forward to as we deadline on the hottest day of the year so far! It was wonderful to see the sun shining on Glastonbury this year with some incredible performances beamed straight into your home. But remember, Glastonbury would be nothing if wasn’t for the unique grass roots music culture we have in this country, so while it’s fantastic to see the festival vibe on the red button it’s nowhere near as good as actually being there. Tickets may be scarce for Glastonbury but there are literally hundreds of festivals July 2019 up and down the country that need your support... In the following pages we look back at two very different local festivals for you, Wychwood in Cheltenham and Hopfest in SLAP MAGAZINE Bewdley just to get you in the festy mood. Unit 3a, Lowesmoor Wharf, This months local festivals include our very own mini Glasto in Worcester WR1 2RS Noztock the Hidden Valley near Bromyard, The brilliant 2000 Trees in Cheltenham, El Darado in Ledbury and Linton in Ross- on- Wye, Telephone: 01905 26660 to name but a few. -

ST/LIFE/PAGE<LIF-004>

D4 life happenings | THE STRAITS TIMES | FRIDAY, AUGUST 2, 2019 | GIGS A Blast From The Past Anjali Raguraman recommends By Choy! (Singapore) Choy! is a Siva Choy tribute band formed by Siraj Aziz, Rajiv Singh, Picks CE LA VI PRESENTS a residency at Ireland’s Kremlin club Don Aaron, Nathanael Nilesh and KRISTIAN NAIRN AKA HODOR for 11 years and also played at famed Akshara Thiru. Coming from diverse Gig It will be a “rave of thrones” at roof-top clubs around the world such as Las backgrounds, the band seek to club lounge Ce La Vi with DJ Kristian Vegas’ Hakkasan and Ibiza’s Amnesia. celebrate the life of the late Nairn (left), who is best known for WHERE: Ce La Vi Club Lounge, Singapore comedian and artists of playing Hodor on award-winning Marina Bay Sands Tower 3, yesteryear by sharing their television show Game Of Thrones. 1 Bayfront Avenue MRT: Bayfront repertoire and musings with fellow The club will be transformed into WHEN: Aug 16, 10pm till late Singaporeans, in the hope of the houses of Westeros, complete ADMISSION: $28, includes one inspiring the next generation. with an Iron Throne. premium pour. For table reservations, WHERE: Esplanade Outdoor Theatre, Expect big room and house tunes call 6508-2188 or e-mail 1 Esplanade Drive MRT: Esplanade/ by the Northern Irish DJ, who held [email protected] City Hall WHEN: Sun, 7.15 & 8.30pm ADMISSION: Free INFO: www.esplanade.com YOUTH X WEEKEND FESTIVAL Zrina Two events taking place this weekend Zrina’s music is an invitation to at the Singapore Sports Hub explore her journey of growth – from celebrate youth – the Music For singing cartoon theme tunes and A Cause festival and Shine Live listening to 16-bit music while playing showcase. -

International Education Column 20191218

CHINA DAILY Wednesday, December 18, 2019 | 19 YOUTH estlife is used to adula Feehily, Filan and former member tion. The Irish pop Bryan McFadden, who departed the band is a global phe lineup in 2004, Westlife was formed nomenon and sells out in 1998 and their selftitled debut concert venues the world over. But W album, which was released in the even the band members were sur United Kingdom in November prised at the enthusiastic reception Westlife in tune 1999, was a smash hit. they got in Shanghai on Aug 16. With their records selling over 55 Arriving at the city’s National million worldwide, the thenboy Exhibition and Convention Center group achieved 14 UK No 1 singles, for an afternoon rehearsal they were including Flying Without Wings warmly welcomed by more than and You Raise Me Up, and their ver 5,000 waiting fans. sion of Phil Collins’ Against All “When they cheered and sang our with their fans Odds, recorded with pop diva Mari song, My Love, we were so touched ah Carey. and amazed,” recalls singersong On Nov 15, their new album, writer Shane Filan, a member of Irish band overwhelmed by rapturous welcome titled Spectrum, was released, Westlife, in an interview with China which was their first since the 2010 Daily. they receive in China, Chen Nan reports. album, Gravity. The band disband They also performed in the first ed in 2012 and reunited in 2018. Tencent Music Entertainment Recorded in Dublin, Los Angeles Awards, which was held in Macao and London, the 11song new on Dec 8. -

The Waterville Mail (Vol. 39, No. 09): August 7, 1885

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine) Waterville Materials 8-7-1885 The Waterville Mail (Vol. 39, No. 09): August 7, 1885 Maxham & Wing Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/waterville_mail Part of the Agriculture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Maxham & Wing, "The Waterville Mail (Vol. 39, No. 09): August 7, 1885" (1885). The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine). 1145. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/waterville_mail/1145 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Waterville Materials at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. ^nsiness ^jlplnttrviUe a. 8. JPALMJ3R, r.ni. MAXHAM. 0At»'b B. WINO. ihftTOIM AlW' rBomfBTOBB. StJRQEON DENTIST. bVFIOV*^ llAiH Stbibt, rvNonsen.se I a Great alihrc of this dis IU((tII>KKCK—« COLLBSB Stbibt, Oobmbb or Obtobbu. Htbbbt. pute about the burial pl.icc ofGen.Crant’.s [fra If (trout^Oxide das oonilantl4/ body. Much of it is limited to a few lo Md. cal correspondents, at Washington anil elsewhere, in the hire rif private or sec ^ A. ROBERTS, M.D. tional interests or wWms. 'The grea' VOL. XXXIX. Waterville, Maine.................Friday, A.ngust 7”, 1885. NO. 9. body of the people king settled the OFFICE AT RESIDENCE proprie'WrsIlip of tlie de'ad liodies of their OOLLiBB Stbbbt, On. Elmwood Iotbl grant men, by concCtlJng them W their ^ orricB 1IOUB8. • threw oflT his coat and his highly fashion " 'This Is a queer joke of yours, lie jj^iscellnnS' able shoes, too fashionable for cnmforUi- (iimilics and their homes, — W.ashington I 114101 A.H. -

SPRINCJ L Vjazette

ilBKARY p,,». » " 'V „ h i Betnil vcnu# \ S PRINC J L i . i vjAZETTE Manasquan Seaside Established 1877 Gazette and Mirror Established 188a VOL XLV-NO 22 Si K:\ij LAKE, N, J., FRIDAY, JUNE 2. 1!»22 $2.00 PER YEAR i Third Avenue Paving A Defence O fiered An Important Sale Hoffmeistcrs Go Abroad The business part o f Third ave T o Honor a Hero To the Editor of the Gnzo-v 1 Lowlands," that beautiful . estate Mr 'in > Mi . A F Hoffmeistcr, nue is still in a state o f eruption, but It ha.-, been suggested that one of it is to be regretted tlia’ ui.jum | which cover, the entii. block bound- •vho pe?it the w in ter on their place there are indications that the day of the most fitting, yet simple, orna who believes in God and who -I.o.,! j r,! G .cun, Pro..pert. Lorraine anil at Poit Sew ail, Florida, tml who have completion is nearing its dawn ments to t lie Community Hou.-e therefore love his neighbor a.- i, i. ^L-w-oi iwnii-., funnei ly owned by been occupy mu their beautiful estate* Much o f the first work has been would be a tablet to the memory of self, should attack another s faith ti - - licnt y W elsh Roger, and pur “ Alanna-in the Pines”, on Pitney ave of a character that did not show the Robinson - Worthington. the contributor did last week. C! t- et, led about two year- ago b y Mr nue since April, will leave Spring actual progress made. -

M a Y T O D E C E M B E R 2 0

FEBRUARY TO MAY 2019 MAY TO DECEMBER 2019 DARKES LANE | POTTERS BAR | HERTS Red Joan (12A) Kalank (12A) Thurs 23rd May 7.30pm Sat 1st June 7.30pm Mon 27th May 7.30pm Tues 28th May 7.30pm Tickets £7.50, £5.50 CHILD Set in pre-independent India this is a story Joan Stanley (Judi Dench), lives in contented about an elite family and many of its hidden retirement. Then suddenly her tranquil truths. existence is shattered as she’s shockingly arrested by MI5. For Joan has been hiding an Ticket price includes tea and Indian snacks. incredible past; she is one of the most influential spies in living history. (1hr 50mins) Tolkien (12A) Long Shot (15) Mon 3rd June 1pm Mon 3rd June 3.45pm Tues 4th June 3.45pm Tues 4th June 7.30pm Weds 5th June 1pm Weds 5th June 3.45pm Thurs 6th June 7.30pm Thurs 6th June 3.45pm Explores the formative years of the orphaned When Fred Flarsky reunites with his first crush, author as he finds friendship, love and artistic one of the most influential women in the world, inspiration among a group of fellow outcasts Charlotte Field, he charms her. As she prepares to at school. (1hr 52mins) make a run for the Presidency, Charlotte hires Fred as her speechwriter and sparks fly. (2hrs 5mins) CINEMA PRICES Daytime Evening Adult £6.00 £6.50 Concs £5.50 £6.00 Children £4.50 £5.50 includes 50p Venue Levy, no booking fees. Rocketman (cert TBC) The Hustle (12A) Fri 21st June 1pm Tues 25th June 1pm, 3.45pm Coming soon Weds 26th June 1.30pm Mon 1st Jul 7.30pm Anne Hathaway and Rebel Wilson star as Weds 3rd Jul 7.30pm female scam artists, one low rent and the other high class, who team up to take down A musical fantasy about the fantastical human the men who have wronged them. -

Gallagher Claims Liam Quit Beady Eye by Text Message

24 Friday Friday, December 21, 2018 Lifestyle | Gossip Gallagher claims Liam quit Beady Eye by text message iam Gallagher quit Beady Eye by text message, his estranged Man, he didn’t even have the balls to phone his bandmates. Because brother Noel Gallagher has claimed. The ‘Greedy Soul’ he got a solo deal, it was, See you later, lads. Then when he got his Lsinger formed the band with the other remaining members deal with Live Nation, no one was telling him, ‘Don’t do any Oasis of Oasis - Gem Archer, Andy Bell and Chris Sharrock - after Noel songs, do your new stuff, that’s what your good at.’ “ Once he knew quit the group in August 2009 following a backstage bust-up be- that Beady Eye was finished Noel had no hesitation in welcoming tween the brothers before a headline appearance at a Paris music Gem and Chris into his group and the timing was perfect because festival. Beady Eye disbanded in October 2014 after releasing two two of his members had decided to quit the High Flying Birds the albums, ‘Different Gear, Still Speeding’ and ‘BE’, and now guitarist same year. The rock legend said: “When I first started [as a solo Gem and drummer Chris play in Noel’s touring band the High Fly- artist], I had Tim [Smith, guitar] and Jeremy [Stacey, drums], and ing Birds. The ‘Wonderwall’ songwriter has accused Liam of not the great thing about session musicians is that when you’re not having the guts to tell his friends he was walking away from the sure what you’re doing, they’re bang on it, they make it sound like group to their faces or even in a phone call and instead sent them the record. -

Westlife in Tune with Their Fans

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Wednesday, December 18, 2019 | 19 YOUTH estlife is used to adula Feehily, Filan and former member tion. The Irish pop Bryan McFadden, who departed the band is a global phe lineup in 2004, Westlife was formed nomenon and sells out in 1998 and their selftitled debut concertW venues the world over. But album, which was released in the even the band members were sur United Kingdom in November prised at the enthusiastic reception 1999, was a smash hit. they got in Shanghai on Aug 16. Westlife in tune With their records selling over 55 Arriving at the city’s National million worldwide, the thenboy Exhibition and Convention Center group achieved 14 UK No 1 singles, for an afternoon rehearsal they were including Flying Without Wings warmly welcomed by more than and You Raise Me Up, and their ver 5,000 waiting fans. sion of Phil Collins’ Against All “When they cheered and sang our with their fans Odds, recorded with pop diva Mari song, My Love, we were so touched ah Carey. and amazed,” recalls singersong On Nov 15, their new album, writer Shane Filan, a member of Irish band overwhelmed by rapturous welcome titled Spectrum, was released, Westlife, in an interview with China which was their first since the 2010 Daily. they receive in China, Chen Nan reports. album, Gravity. The band disband They also performed in the first ed in 2012 and reunited in 2018. Tencent Music Entertainment Recorded in Dublin, Los Angeles Awards, which was held in Macao and London, the 11song new on Dec 8. -

Unusual (UNU SP)

Initiating Coverage Singapore 17 September 2019 Consumer Discretionary | Media & Entertainment UnUsUaL (UNU SP) Buy Shares On Sale Now! While Stocks Last!; BUY Target Price (Return) SGD0.42 (+50%) Price: SGD(+18%)0.28 Market Cap: USD206m 0.09m/0.06m Avg Daily Turnover (SGD/USD) Initiate with a BUY with SGD0.42 TP, 50% upside. UnUsUaL is an Asian Analysts concert promotion and event production leader. It has grown since listing into an entity with FY19 earnings of SGD13.2m (CAGR: +53%). Given more Jarick Seet entertainment opportunities ahead, this should help grow a conservative +65 6232 3891 FY20F-22F NPAT CAGR of 20%. Its share price has also corrected [email protected] significantly to a reasonable valuation. Consequently, we initiate coverage on a rare local firm that can still deliver high growth over the next 2-3 years. Lee Cai Ling Scalable and resilient business model – branching globally. UnUsUaL +65 6232 3892 has a scalable business model. It can leverage on strong relationships with [email protected] various artistes, and is able to host concerts in various venues globally, especially China. Top artistes can easily tour 40-60 cities in 1-2 years, and Share Performance (%) UnUsUaL has tested and proven the success of this concept, having brought YTD 1m 3m 6m 12m Chinese singer GEM to San Francisco for sold-out concerts in March and Absolute (20.5) (4.9) (3.3) (1.7) (34.1) Singaporean artiste JJ Lin for sold-out shows in Sydney and Melbourne. Relative (23.0) 1.4 (0.9) 1.6 (31.1) Expansion into family entertainment shows. -

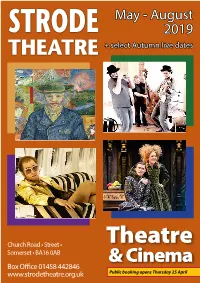

May - August 2019 + Select Autumn Live Dates

May - August 2019 + select Autumn live dates Church Road • Street • Theatre Somerset • BA16 0AB & Cinema Box Office 01458 442846 www.strodetheatre.org.uk Public booking opens Thursday 25 April Welcome to our brochure for Summer season ...with some treats from the autumn season too... WELCOME Summer is almost upon us already. Last year, the weather was so hot that - together with the World Cup - it turned out that not too many folk wanted to came out and play at the theatre or cinema! I know we were not alone -many theatres and visitor attractions really ‘took a hit’ last year. The summer before, on the other hand, we had a ‘bumper’ summer season; such is the nature of the game! Without knowing how the Look out for the Family weather is going to turn out, it is difficult to programme appropriately Friendly logo. –so we have to hedge our bets! This season, I hope you are able to enjoy something from our wide programme of films, live broadcasts and live This indicates films, shows shows. So that you can enjoy the warm evenings as well as top qulaity films, I’m very pleased that we have partnered once again with Alfred and live transmissions that Gillett Trust and now also with Clarks Village to give you yet another are appropriate for all ages Outdoor Cinema season! (see page 40) and fun for all the family. I’m also very glad to be able to tell you that we have just received a small award from Film Hub South West - a regional division of the British Film Institute (BFI) - for our British, international and independent film programme in 2018.