Colorado River Project, Texas,” Volume 1, 1936, 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Look at the Texas Hill Country Following the Path We Are on Today Through 2030

A Look at the Texas Hill Country Following the path we are on today through 2030 This unique and special region will grow, but what will the Hill Country look like in 2030? Growth of the Hill Country The Hill Country Alliance (HCA) is a nonprofit organization whose purpose is to raise public awareness and build community support around the need to preserve the natural resources and heritage of the Central Texas Hill Country. HCA was formed in response to the escalating challenges brought to the Texas Hill Country by rapid development occurring in a sensitive eco-system. Concerned citizens began meeting in September of 2004 to share ideas about strengthening community activism and educating the public about regional planning, conservation development and a more responsible approach growth in the Hill Country. This report was prepared for the Texas Hill Country Alliance by Pegasus Planning 2 Growth of the Hill Country 3 Growth of the Hill Country Table of Contents Executive Summary Introduction The Hill Country Today The Hill Country in 2030 Strategic Considerations Reference Land Development and Provision of Utilities in Texas (a primer) Organizational Resources Materials Reviewed During Project End Notes Methodology The HCA wishes to thank members of its board and review team for assistance with this project, and the authors and contributors to the many documents and studies that were reviewed. September 2008 4 Growth of the Hill Country The Setting The population of the 17-County Hill Country region grew from approximately 800,000 in 1950 (after the last drought on record) to 2.6 million in 2000. -

Intensive Survey of Barton Creek Segment 1430

INTENSIVE SURVEY OF BARTON CREEK SEGMENT 1430 May 20-24, 1985 Hydrology, Field Measurements, Water Chemistry and Biology By Stephen R. Twidwell IS 86-01 Texas Water Commission February 1986 ABSTRACT An intensive survey of Barton Creek (Segment 1430) was conducted May 20-24, 1985, by the Texas Department of Water Resources. The study area included the entire length of Barton Creek from its union with Town Lake in Austin to its headwaters in western Hays County. Water quality, hydraulic, and biological data were collected at 20 mainstream stations and two tributary streams. Stream widths of Barton Creek generally increased from upstream to downstream (range 5.2 - 22.9 m). Stream discharge increased from 0.0129 m3/s (0.46 ft3/s) near the headwaters to 0.3894 m3/s (13.75 ft3/s) at Lost Creek Boulevard, and then declined to 0.0372 m3/s (1.32 ft3/s) upstream of Barton Pool as the water flowed over the Edwards Aquifer recharge zone and infiltrated to the underground. Stream velocities were slow throughout the study area (range 0.04 - 0.07 m/s). Excepting one early morning measurement, dissolved oxygen levels remained above the 5 mg/L segment criterion. Nutrient and chlorophyll a levels were below or near the lower limits of detection throughout the segment. Stream CBOD5 and CBOD2o levels were low throughout Barton Creek. Chloride, sulfate, total dissolved solids, water temperature, and pH levels conformed to segment criteria. Benthic macroinvertebrate community structure reflected clean water and healthy environmental conditions throughout the -

Stephen F. Austin and the Empresarios

169 11/18/02 9:24 AM Page 174 Stephen F. Austin Why It Matters Now 2 Stephen F. Austin’s colony laid the foundation for thousands of people and the Empresarios to later move to Texas. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA Moses Austin, petition, 1. Identify the contributions of Moses Anglo American colonization of Stephen F. Austin, Austin to the colonization of Texas. Texas began when Stephen F. Austin land title, San Felipe de 2. Identify the contributions of Stephen F. was given permission to establish Austin, Green DeWitt Austin to the colonization of Texas. a colony of 300 American families 3. Explain the major change that took on Texas soil. Soon other colonists place in Texas during 1821. followed Austin’s lead, and Texas’s population expanded rapidly. WHAT Would You Do? Stephen F. Austin gave up his home and his career to fulfill Write your response his father’s dream of establishing a colony in Texas. to Interact with History Imagine that a loved one has asked you to leave in your Texas Notebook. your current life behind to go to a foreign country to carry out his or her wishes. Would you drop everything and leave, Stephen F. Austin’s hatchet or would you try to talk the person into staying here? Moses Austin Begins Colonization in Texas Moses Austin was born in Connecticut in 1761. During his business dealings, he developed a keen interest in lead mining. After learning of George Morgan’s colony in what is now Missouri, Austin moved there to operate a lead mine. -

THE TEXAS CONFEDERATE HOME for MEN, 1884-1970 Amy Sue Kirchenbauer, B.A

THE TEXAS CONFEDERATE HOME FOR MEN, 1884-1970 Amy Sue Kirchenbauer, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Richard Lowe, Major Professor Richard McCaslin, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Harland Hagler, Committee Member James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kirchenbauer, Amy Sue, The Texas Confederate Home for Men, 1884-1970. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 116 pp., bibliography, 91 titles. Founded in 1886 by a local veteran’s organization, the Texas Confederate Home for Men served thousands of veterans throughout its tenure. State-run beginning in 1891, the facility became the center of controversy multiple times, with allegations of mistreatment of residents, misappropriation of funds, and unsanitary conditions in the home. Despite these problems, for several decades the home effectively provided large numbers of needy veterans with a place where they could live out their remaining years. The home was finally closed by the state in 1965, and the buildings were demolished in 1970. The facility’s success helped to inspire Texas to introduce a veteran pension system, and brought forth a new era in the state’s willingness to take care of veterans once their wars were over. Copyright 2011 by Amy Sue Kirchenbauer ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would not have been completed without the guidance of Dr. Richard Lowe. He urged me frequently to move beyond the limits of what I thought myself to be capable of, and I am a better historian for it. His dedication to helping me achieve my dreams and hours spent editing my efforts will always be appreciated. -

Central Texas Highland Lakes

Lampasas Colorado Bend State Park 19 0 Chappel Colo rado R. LAMPASAS COUNTY 2657 281 183 501 N W E 2484 S BELL La mp Maxdale asa s R Oakalla . Naruna Central Texas Highland Lakes SAN SABA Lake Buchanan COUNTY Incorporated cities and towns 19 0 US highways Inks Lake Lake LBJ Other towns and crossroads 138 State highways Lake Marble Falls 970 Farm or Ranch roads State parks 963 Lake Travis COUNTY County lines LCRA parks 2657 Map projection: Lambert Conformal Conic, State 012 miles Watson Plane Coordinate System, Texas Central Zone, NAD83. 012 km Sunnylane Map scale: 1:96,000. The Lower Colorado River Authority is a conservation and reclamation district created by the Texas 195 Legislature in 1934 to improve the quality of life in the Central Texas area. It receives no tax money and operates on revenues from wholesale electric and water sales and other services. This map has been produced by the Lower Colorado River Authority for its own use. Accordingly, certain information, features, or details may have been emphasized over others or may have been left out. LCRA does not warrant the accuracy of this map, either as to scale, accuracy or completeness. M. Ollington, 2003.12.31 Main Map V:\Survey\Project\Service_Area\Highland_Lakes\lakes_map.fh10. Lake Victor Area of Detail Briggs Canyon of the Eagles Tow BURNETBURNET 963 Cedar 487 Point 138 2241 Florence Greens Crossing N orth Fo rk Joppa nGab Mahomet Sa rie l R Shady Grove . 183 2241 970 Bluffton 195 963 COUNTYCOUNTY Lone Grove Lake WILLIAMSONWILLIAMSON 2341 Buchanan 1174 LLANOLLANO Andice 690 243 Stolz Black Rock Park Burnet Buchanan Dam 29 Bertram 261 Inks La ke Inks Lake COUNTYCOUNTY Buchanan Dam State Park COUNTYCOUNTY 29 Inks Dam Gandy 2338 243 281 Lla no R. -

Rough Hollow Community.Pdf

ituated in the middle of it all, nestled on the shores of Lake Travis in the city of Lakeway, sits Rough Hollow – a master planned community of stunning vistas, exquisite shorelines and classically-constructed homes. With waterfront amenities, award-winningS golf courses, and hundreds of shops, restaurants and events within minutes, it’s easy to see how roughing it here means having it all! Rough Hollow’s new water-themed amenity, Highland Village, raised the neighborhood’s amenity offerings to soaring new heights. With the Laziest River, splash pads, a children’s pool, adult pool with swim-up bar, all-season pavilion with a demonstration kitchen, a village green and an open-air marketplace, Highland Village gives residents a place to socialize, dine, play and relax. Schools Resident Member Advantages • Private Yacht Club and a 290 wet-slip full service marina Lake Travis Independent School District • Patio sun deck with lounge www.ltisdschools.org • Water theme community center with lazy river, splash pads Serene Hills Elementary School 512-533-7400 • All season event pavilion 3301 Serene Hills Drive, Austin TX 78738 • Planned year round activities for both adults and little ones Lake Travis Middle School • Fitness center/cardio studio 512-533-6200 4932 Highlands Blvd., Spicewood TX 78669 • Resort-style, infinity edge swimming pool Lake Travis High School • Canyon Grille at Rough Hollow Yacht Club • Fully stocked ship store 512-533-6100 3322 Ranch Road 620 S, Austin TX 78738 • Miles of hike and bike trails • Amphitheatre • Texas Hill -

Cielo Vista Residential Land Village of Volente :: Volente, Tx

CIELO VISTA RESIDENTIAL LAND VILLAGE OF VOLENTE :: VOLENTE, TX FOR MORE INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT: 33 LOTS FOR SALE Colin Armstrong Land Services Group +1 512 499 4973 [email protected] CBRE | 100 Congress Ave. | Suite 500 | Austin, TX 78701 CIELO VISTA RESIDENTIAL LAND VILLAGE OF VOLENTE :: VOLENTE, TX CIELO VISTA EXCELLENT SCHOOLS Cielo Vista is a planned subdivision located on more Cielo Vista is located within the Leander Independent than 1,100 acres in western Travis County. Lots within School District, which is a Texas Education Agency the project are sited on a prominent ridge rising 300 “Recognized” school district, one of only a handful feet above Lake Travis and offer premier views of the in Central Texas. The quality of the schools in the lake and 4,000 acres of protected preserve land in area has proven to be a major driver of the area’s the surrounding Texas Hill Country. The remainder of rapid growth over the past 10 years. On the Texas the tract is set aside for habitat and nature preserve. Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS) tests, in Residents located within the MUD will have access to all the “All Students” category, greater than 90 percent of of the adjacent 800 acres for recreational purposes. LISD students pass the TAKS test, at every grade level, in every subject tested. LAKE TRAVIS Lake Travis was highlighted in Kiplinger.com’s report on the top places to live. According to their article, “Once mostly a resort community for retirees, this 11-mile stretch of land increasingly appeals to young families who like the small-town atmosphere and easy access to Austin and Round Rock”. -

Austin New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 2Q18

Austin New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 2Q18 ID PROPERTY UNITS 89 Alexan Capitol 272 179 South Congress Avenue 268 204 Thomas Ranch 300 90 Avenue, The 135 180 550 205 110 1 Hanover Oak Hill 370 Granada Ridge East Street Village 91 Block 71 236 206 60 2 Inspire on 22nd 129 181 Santal Phase III, The 1412 Emli at Leander 92 Block 87 100 182 Hays Common 50 207 Leander Place 70 3 Ruckus 2.0, The 67 93 GreenWater Block 185 387 4 North Creek 310 183 Lenox Springs Phase II 260 208 Merritt Lakeline Station 200 94 Travis, The 422 184 Manchaca Commons 240 209 Pointe at Brushy Creek, The 150 5 Springs at Sunfield 256 95 AMLI South Shore Phase II 178 127 6 Palo Verde 596 185 Community First Village 100 210 Merritt Estates 300 96 Aspen Heights Riverside 325 186 Eastridge 300 112 211 Villagio at Forest Creek, The 110 7 Overture Arboretum 184 97 Lakeshore Pearl Redevelopment 425 8 Legacy 83 187 Sun Chase 760 57 212 Merritt Cornerstone 200 98 Lenox Oaks 356 188 893 213 Pointe at Mirror Lake, The 150 9 Walnut Park 283 99 Mont, The 288 Velocity Crossing 189 930 214 59 10 Park at Crystal Falls Phase II 238 100 South Shore District Phase IV 324 Lagos 308 Guadalupe Street 215 70 11 22 North 240 101 South Shore Highline 102 190 Belterra Village Senior Housing 200 Aria Grand 12 Crestview Commons 353 102 Saint Elmo Market District 386 191 Blanco River Walk 312 33 216 Cambrian East Riverside 65 13 Ace, The 330 103 Soco 261 192 Centerpoint Road & South Old Bastrop Hwy 300 32 217 Casa Madera 80 14 Santal Phase II, The 212 193 Emli at East Village -

TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America

Capitol Area Council TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America TRAIL REQUIREMENTS: 1. There should be at least one adult for each 10 hikers. A group must have an adult leader at all times on the trail. The Boy Scouts of America policy requires two adult leaders on all Scout trips and tours. 2. Groups should stay together while on the hike. (Large groups may be divided into several groups.) 3. Upon completion of the trail the group leader should send an Application for Trail Awards with the required fee for each hiker to the Capitol Area Council Center. (Only one patch for each participant.) The awards will be mailed or furnished as requested by the group leader. Note: All of Part One must be hiked and all points (1-15) must be visited. Part Two is optional. HIKER REQUIREMENTS: 1. Any registered member of the Boy Scouts of America, Girl Scouts, or other civic youth group may hike the trail. 2. Meet all Trail requirements while on the hike. 3. The correct Scout uniform should be worn while on the trail. Some article (T-shirt, armband, etc) should identify other groups. 4. Each hiker must visit the historical sites, participate in all of his/her group’s activities, and answer the “On the Trail Quiz” to the satisfaction of his/her leader. Other places of interest you may wish to visit are: Zilker Park and Barton Springs Barton Springs Road Elisabet Ney Museum 304 E. 34th. Street Hike and Bike Trail along Town Lake Camp Mabry 38th. Street Lake Travis FM #620 Lake Austin FM # 2222 Capitol Area Council TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America ACCOMODATIONS: McKinney Falls State Park, 5805 McKinney Falls Parkway, Austin, TX 78744, tel. -

For Immediate Release COLORADO RIVER ALLIANCE ANNOUNCES

For Immediate Release COLORADO RIVER ALLIANCE ANNOUNCES NEW EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AUSTIN, Texas (September 21, 2015) – The Colorado River Alliance Board of Directors is pleased to welcome R. Brent Lyles as the organization’s new Executive Director. Lyles is already a proven leader and advocate for the Texas Colorado River, and is thus a strong fit for advancing the Alliance’s mission. Lyles begins his new position at the Alliance on October 1st. Lyles brings over 25 years of nonprofit and science-education experience to the Alliance, most recently heading Austin Youth River Watch, an after-school and summer program for at-risk teens, engaging them in water-quality monitoring in the Colorado River’s watershed. “On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Colorado River Alliance, I am pleased to welcome R. Brent Lyles as the new Executive Director,” said Board President Kyndel Bennett. “His wealth of experience in environmental education and his demonstrated leadership will help the Alliance move forward in its mission to secure the vitality of the Texas Colorado River through education and advocacy for all generations.” As Executive Director of the Alliance, Lyles will oversee an organization that connects more than 15,000 students every year to high-quality education programs about water conservation and the Texas Colorado River. The Alliance also provides environmental science and outdoor education programs for community members, such as river cleanups and public lectures, bringing awareness about the Texas Colorado River. “This is quite an honor,” Lyles said. “The Alliance is at the forefront of our state’s dialogue about water conservation, and as a long-time, personal advocate for a healthy, flowing Colorado River, I couldn’t be more excited about the important work ahead.” Lyles’s community involvement includes serving as a Board member of EarthShare of Texas, the American Genre Film Archive, and Leadership Austin. -

Travis County Early Voting Locations November 3, 2020 General Election

EXHIBIT B Travis County Early Voting Locations November 3, 2020 General Election Sitios de Votación Adelantada del Condado de Travis, para las Elecciones General del 3 de noviembre de 2020 Early Voting begins Tuesday, October 13 and ends on Friday, October 30 subject to change DANA DEBEAUVOIR, La Votación Adelantada empieza el martes, 13 de octubre y termina el viernes, 30 de octubre sujeto a cambios COUNTY CLERK Monday—Saturday (7am - 7pm), Sunday (Noon - 6pm) * except where noted lunes—sábado (7am - 7pm), domingo (mediodía - 6pm) * excepto donde se indique * MEGA-CENTERS will remain open until 9pm on October 28, 29 and 30th * MEGA-CENTROS estarán abiertos hasta 9pm el 28, 29 y 30 de octubre CENTRAL: Austin Central Library MEGA-CENTER * 710 W Cesar Chavez St Austin 78701 Austin Recreation Center at House Park 1301 Shoal Creek Blvd Austin 78701 Big Brothers Big Sisters of Central Texas 4800 Manor Rd Austin 78723 Holiday Inn Austin Midtown 6000 Middle Fiskville Rd Austin 78752 UT Flawn Academic Center 2304 Whitis Ave Austin 78712 UT Gregory Gym 2101 Speedway Austin 78712 Virginia L. Brown Recreation Center 7500 Blessing Ave Austin 78752 NORTH / NORTE: Pflugerville ISD Rock Gym MEGA-CENTER * 702 W Pecan St Pflugerville 78660 Chinatown Center 10901 N Lamar Blvd Austin 78753 Courtyard by Marriott Austin Pflugerville 16100 Impact Way Pflugerville 78660 Disability Rights Texas 2222 W Braker Ln Austin 78758 Gus Garcia Recreation Center 1201 E Rundberg Ln Austin 78753 Renaissance Austin Hotel at The Arboretum 9721 Arboretum Blvd Austin 78759 -

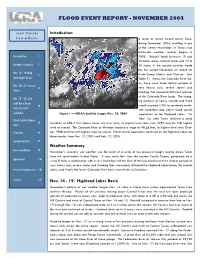

2004 Flood Report

FLOOD EVENT REPORT - NOVEMBER 2004 Lower Colorado Introduction River Authority A series of storms moved across Texas during November 2004, resulting in one of the wettest Novembers in Texas since statewide weather records began in Introduction 1 1895. Rainfall totals between 10 and 15 inches across Central Texas and 17 to Weather Summary 1 18 inches in the coastal counties made this the wettest November on record for Nov. 14 - 19: High- 1 Austin-Camp Mabry and Victoria (See land Lakes Basin Table 1). Across the Colorado River ba- sin, there were three distinct periods of Nov. 20 - 21: Coastal 3 very heavy rain, severe storms and Plains flooding that impacted different portions of the Colorado River basin. The chang- Nov. 22 - 23: Colo- ing patterns of heavy rainfall and flood rado River Basin 4 runoff required LCRA to constantly evalu- from Austin to ate conditions and adjust flood control Columbus Figure 1 — NOAA Satellite Image, Nov. 22, 2004 operations on the Highland Lakes. On Flood Control Opera- Nov. 24, Lake Travis reached a peak 5 elevation of 696.7 feet above mean sea level (msl), its highest level since June 1997 and the fifth highest tions level on record. The Colorado River at Wharton reached a stage of 48.26 feet, its highest level since Octo- Summary 6 ber 1998 and the ninth highest level on record. Flood control operations continued on the Highland Lakes for three months, from Nov. 17, 2004 until Feb. 17, 2005. Rainfall Statistics 7 Weather Summary 9 River Conditions November’s unusually wet weather was the result of a series of low pressure troughs moving across Texas from the southwestern United States.