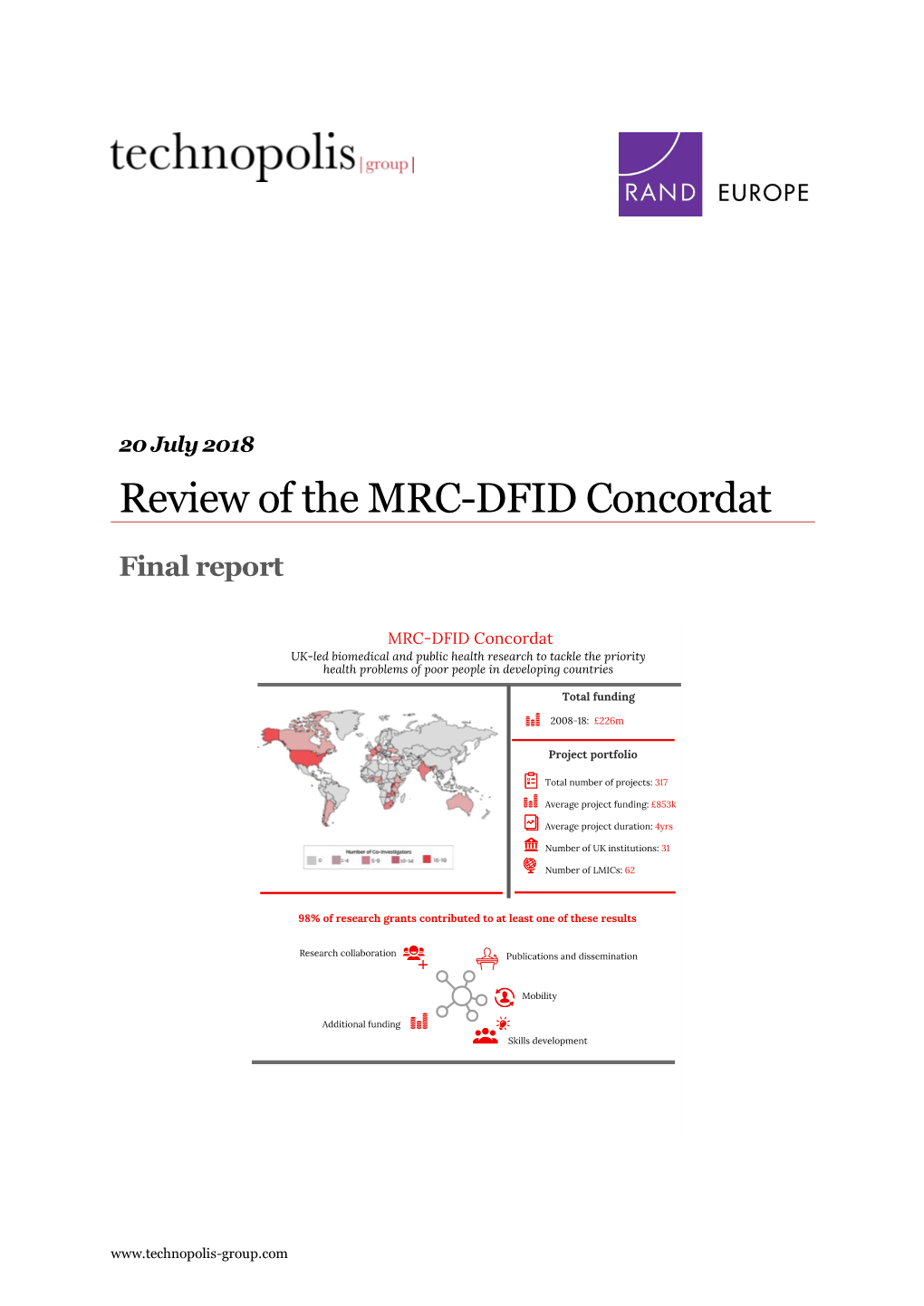

MRC Review of the MRC-DFID Concordat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coronavirus: Covid-19 Has Killed More People Than SARS and MERS Combined, Despite Lower Case Fatality Rate

BMJ 2020;368:m641 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m641 (Published 18 February 2020) Page 1 of 1 News BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.m641 on 18 February 2020. Downloaded from NEWS Coronavirus: covid-19 has killed more people than SARS and MERS combined, despite lower case fatality rate Elisabeth Mahase The BMJ The novel coronavirus that has so far spread from China to 26 This comment came after the first case of covid-19 was countries around the world does not seem to be as “deadly as confirmed in Africa (in Egypt). Commenting on this milestone other coronaviruses including SARS and MERS,” the World in the outbreak, Trudie Lang, director of the Global Health Health Organization has said. Network at the University of Oxford, said it was “important but At a briefing on 17 February WHO’s director general, Tedros not unexpected.” She highlighted the fact that WHO had Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said that more than 80% of patients declared the outbreak a “public health emergency” to “support with covid-19 have a “mild disease and will recover” and that less well resourced nations in responding and preparing for it is fatal in 2% of reported cases. In comparison, the 2003 cases.” outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) had a Lang praised the response of the Africa Centres for Disease case fatality rate of around 10% (8098 cases and 774 deaths), Control and Prevention, which is based in Ethiopia and supports http://www.bmj.com/ while Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) killed 34% countries with surveillance, emergency responses, and of people with the illness between 2012 and 2019 (2494 cases prevention of infectious disease. -

Annual Meeting

Volume 97 | Number 5 Volume VOLUME 97 NOVEMBER 2017 NUMBER 5 SUPPLEMENT SIXTY-SIXTH ANNUAL MEETING November 5–9, 2017 The Baltimore Convention Center | Baltimore, Maryland USA The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene The American Journal of Tropical astmh.org ajtmh.org #TropMed17 Supplement to The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene ASTMH FP Cover 17.indd 1-3 10/11/17 1:48 PM Welcome to TropMed17, our yearly assembly for stimulating research, clinical advances, special lectures, guests and bonus events. Our keynote speaker this year is Dr. Paul Farmer, Co-founder and Chief Strategist of Partners In Health (PIH). In addition, Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, will deliver a plenary session Thursday, November 9. Other highlighted speakers include Dr. Scott O’Neill, who will deliver the Fred L. Soper Lecture; Dr. Claudio F. Lanata, the Vincenzo Marcolongo Memorial Lecture; and Dr. Jane Cardosa, the Commemorative Fund Lecture. We are pleased to announce that this year’s offerings extend beyond communicating top-rated science to direct service to the global community and a number of novel events: • Get a Shot. Give a Shot.® Through Walgreens’ Get a Shot. Give a Shot.® campaign, you can not only receive your free flu shot, but also provide a lifesaving vaccine to a child in need via the UN Foundation’s Shot@Life campaign. • Under the Net. Walk in the shoes of a young girl living in a refugee camp through the virtual reality experience presented by UN Foundation’s Nothing But Nets campaign. -

Written Evidence Submitted by the BBC

Written evidence submitted by the BBC The DCMS Sub-committee on Online Harms and Disinformation Covid-19 Inquiry April 2020 Executive summary 1. The BBC is the leading public service broadcaster in the UK, with a mission to inform, educate and entertain. Our first public purpose is to provide impartial news and information to help people understand and engage with the world around them, and we deliver this across national, local and global news services.1 2. The Editorial Guidelines are the standards that underpin all our journalism, at all times, including during the Covid-19 pandemic. They apply to all our content, wherever and however it is received. Producing and upholding these Editorial Guidelines is an obligation across the BBC and all output made in accordance with these Editorial Guidelines fulfills our public purposes and meets and goes beyond the requirements of our regulator, Ofcom. 3. Coverage of Covid-19 is dominating the UK news across all platforms. And with a plethora of cross platform content, people are most likely to turn to the BBC’s TV, radio and online services for the latest news on the pandemic (82%)2, significantly more than any other source. 4. BBC News has attracted record audiences across platforms with our nations and regions, UK wide and international coverage highlighting the importance of impartial and accurate news at this time. 5. The BBC remains the UK’s primary source for news. In a world of fake news and disinformation online, audiences said they turn to the BBC for a reliable take on events and this reputation for accuracy and trust sends audiences to the BBC during breaking news and to verify facts.3 During the Covid-19 pandemic 83% of people trust coverage on BBC TV4; and audiences from the UK and around the world have come to BBC News in their millions to stay informed and seek trusted advice on how they can protect themselves and those most at risk. -

Agenda, WHO Ebola Research and Development Summit

WHO Ebola Research and Development Summit Geneva, 11 – 12 May 2015 WHO Executive Board Room Agenda Rapporteur: Elisabeth Heseltine Monday 11 May 2015 8:00-9:00 Registration Session 1: Introduction Chair: John Mackenzie (Curtin University, Australia) 9:00-9:15 Welcome: Margaret Chan, Director-General, World Health Organization (WHO) and Objectives of meeting, expected outcomes: Marie-Paule Kieny, Assistant-Director General, Health Systems and Innovation (WHO) 9:15-9:35 Keynote lecture: The Ebola response/getting to zero (20 min), Bruce Aylward (WHO) 9:35-10:15 Country perspectives on R&D during the Ebola epidemic (10 min each) • Wiltshire Johnson (Pharmacy Board, Sierra Leone) • Stephen Kennedy (Ministry of Health, Liberia) • Mandy Kader Konde (CEFORPAG, Guinea) Discussion (10 min) 10:15-10:45 Coffee break SESSION 2: Main lessons learnt on R&D in the 2014-15 EVD outbreak in West Africa. Main challenges, and factors that facilitated implementation of research activities in the affected countries Chair: Nicole Lurie (HHS/ASPR, USA) 10:45-11:30 What were the known facts, pipelines and major challenges to Ebola R&D when the international emergency was declared in August 2014, and what has been achieved since then? This presentation and discussion will identify crucial knowledge gaps at the start of the outbreak, e.g., in immunopathogenesis, appropriate animal models, use of in vitro data, natural history of disease ; and map out the current (May 2015) achievements in filling these gaps. Peter Jahrling (NIH/NIAID, USA): Addressing knowledge -

Wet News Water Special Interest Group Newsletter

Wet News Water Special Interest Group Newsletter Issue 81, May 2020 WATER SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP Water Water Special Interest Group Special Interest Group News from the IChemE Water Special Interest Group Wet News Water Special Interest Group Newsletter Issue 81, May 2020 Editor: Paul Curtis, email: [email protected] or [email protected] Contents Editorial 1 Backwashings 1 From the Chair - Composting Toilets & Everything the Water Industry is doing on Covid-19 2 Secretary's Report 5 AGM 6 Unflushables 2030? Mapping Change Points for Intervention for Sewer Blockages: Workshop Proceedings 27 & 28 January 2020 6 European Biosolids & Organic Resources Conference & Exhibition, 19 & 20 November 2019 8 Water & Sustainability 9 Wanted: Book Reviewers 9 WATER SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP C0490_17 www.icheme.org/water Water Water Special Interest Group Special Interest Group EDITORIAL I turn on my computer and try to remember what day it is, as one day seems to merge into another – always the same home environment but with different calls on Skype, Teams or conference calls. Sometimes I get a moment from the incessant meetings to catch up on emails or important tasks such as editing this newsletter! The world is in turmoil and the challenges of COVID-19 affect how we, at the @one Alliance (Anglian Water’s Capital Delivery Team) engage with site teams, operations teams and managing a design team working from home, whilst managing home schooling and all the usual demands of life! Little different, I am sure, from most of our readers…….the Summer weather is enticing and looking out the window I see signs of things returning to some sort of normality. -

RESEARCH and DEVELOPMENT GOALS for COVID-19 in AFRICA the African Academy of Sciences Priority Setting Exercise CONTENTS

UPDATE – RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT GOALS FOR COVID-19 IN AFRICA The African Academy of Sciences Priority Setting Exercise CONTENTS Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................3 Aim ............................................................................................................................................................................4 Methods ....................................................................................................................................................................5 Data Analysis .............................................................................................................................................................6 Results ......................................................................................................................................................................7 A. Quantitative Data ..............................................................................................................................................7 1. Virus natural history, transmission and diagnostics .......................................................................................................... 8 2. Animal and environmental research on the virus origin, and management measures at the human-animal interface ........ 9 3. Epidemiology studies ................................................................................................................................................... -

A Bioethics Tool for the Implementation of Global Principles by the Pharmaceutical Industry Daniel J

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 1-1-2017 A Bioethics Tool for the Implementation of Global Principles by the Pharmaceutical Industry Daniel J. Hurst Duquesne University Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Part of the Bioethics and Medical Ethics Commons Recommended Citation Hurst, D. J. (2017). A Bioethics Tool for the Implementation of Global Principles by the Pharmaceutical Industry (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/193 This One-year Embargo is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A BIOETHICS TOOL FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF GLOBAL PRINCIPLES BY THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Daniel J. Hurst, ThM, MDiv December 2017 Copyright by Daniel J. Hurst 2017 A BIOETHICS TOOL FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF GLOBAL PRINCIPLES BY THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY By Daniel J. Hurst Approved August 31, 2017 ________________________________ ________________________________ Henk ten Have, MD, PhD Gerard Magill, PhD Director, Center for Healthcare Ethics The Vernon F. Gallagher Chair Professor of Healthcare Ethics -

Vaccines and Global Health :: Ethics and Policy

Vaccines and Global Health: The Week in Review 6 February 2021 :: Issue 593 Center for Vaccine Ethics & Policy (CVEP) This weekly digest targets news, events, announcements, articles and research in the vaccine and global health ethics and policy space and is aggregated from key governmental, NGO, international organization and industry sources, key peer-reviewed journals, and other media channels. This summary proceeds from the broad base of themes and issues monitored by the Center for Vaccine Ethics & Policy in its work: it is not intended to be exhaustive in its coverage. Vaccines and Global Health: The Week in Review is published as a PDF and scheduled for release each Saturday [U.S.] at midnight [0000 GMT-5]. The PDF is posted and the elements of each edition are presented as a set of blog posts at https://centerforvaccineethicsandpolicy.net. This blog allows full-text searching of over 9,000 entries. Comments and suggestions should be directed to David R. Curry, MS Editor and Executive Director Center for Vaccine Ethics & Policy [email protected] Request email delivery of the pdf: If you would like to receive the PDF of each edition via email [Constant Contact], please send your request to [email protected]. Support this knowledge-sharing service: Your financial support helps us cover our costs and to address a current shortfall in our annual operating budget. Click here to donate and thank you in advance for your contribution. Contents [click on link below to move to associated content] A. Milestones :: Perspectives :: Featured Journal Content B. Emergencies C. -

2018 Compiled Snapshots

Dear WIPO Re:Search Members and Friends, Happy New Year! It comes as no surprise to the WIPO Re:Search community that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has risen to the forefront of the global public health agenda. Since the Consortium’s inception in 2011, BVGH has established numerous WIPO Re:Search collaborations aimed at developing novel drugs to combat drug resistant tuberculosis, outpace emerging antimalarial resistance, and more. Although continued drug development is needed, there is mounting evidence that vaccines are necessary to prevent and circumvent AMR. For example, a recent article demonstrated that if children across 75 countries were vaccinated against pneumonia, the infections prevented would result in 11 million less days of antibiotic use annually. Given the relative costs of vaccines and antibiotics, vaccinations are also a cost-effective approach to AMR control. Beyond drugs, BVGH is also catalyzing vaccine development. Notably, through WIPO Re:Search, researchers at Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH) have formalized a partnership to assess an injection-free administration of a malaria vaccine candidate. Please continue reading this Snapshot to learn more. I am pleased to welcome our two newest Members, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and the University of South Carolina. As we dive into the New Year, BVGH thanks you for your continued support and participation in WIPO Re:Search. And as always, please forward this Snapshot to your colleagues and reach out to us with any partnering requests or ideas. Sincerely, Jennifer Dent President, BVGH Accelerating Diagnostic Development for Tuberculosis The Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), McGill International TB Centre, Stop TB Partnership, Unitaid, and WHO have launched the TB Diagnostics Critical Pathway, an online tool for tuberculosis diagnostic developers. -

Sharing Clinical Trial Data: Maximizing Benefits, Minimizing Risk

This PDF is available from The National Academies Press at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=18998 Sharing Clinical Trial Data: Maximizing Benefits, Minimizing Risk ISBN Committee on Strategies for Responsible Sharing of Clinical Trial Data; 978-0-309-31629-3 Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine 280 pages 6 x 9 PAPERBACK (2015) Visit the National Academies Press online and register for... Instant access to free PDF downloads of titles from the NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL 10% off print titles Custom notification of new releases in your field of interest Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Request reprint permission for this book Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Sharing Clinical Trial Data: Maximizing Benefits, Minimizing Risk Sharing Clinical Trial Data Maximizing Benefits, Minimizing Risk Committee on Strategies for Responsible Sharing of Clinical Trial Data Board on Health Sciences Policy PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Sharing Clinical Trial Data: Maximizing Benefits, Minimizing Risk THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, NW Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. -

The Week in Review

The Sentinel Human Rights Action: Humanitarian Response: Health: Holistic Development:: Sustainable Resilience __________________________________________________ Period ending 22 August 2015 This weekly digest is intended to aggregate and distill key content from a broad spectrum of practice domains and organization types including key agencies/IGOs, NGOs, governments, academic and research institutions, consortiums and collaborations, foundations, and commercial organizations. We also monitor a spectrum of peer-reviewed journals and general media channels. The Sentinel’s geographic scope is global/regional but selected country-level content is included. We recognize that this spectrum/scope yields an indicative and not an exhaustive product. The Sentinel is a service of the Center for Governance, Evidence, Ethics, Policy & Practice (GE2P2), which is solely responsible for its content. Comments and suggestions should be directed to: David R. Curry Editor & Founding Director GE2P2 – Center for Governance, Evidence, Ethics, Policy, Practice The Sentinel is also available as a pdf document linked from this page: http://ge2p2-center.net/ Editor’s Note: The Sentinel resumes publication today following annual leave for the editor. This edition covers highlights for the interim period since 2 August 2015. _____________________________________________ Contents [click on link below to move to associated content] :: Week in Review :: Key Agency/IGO/Governments Watch - Selected Updates from 30+ entities :: INGO/Consortia/Joint Initiatives Watch - Media Releases, Major Initiatives, Research :: Foundation/Major Donor Watch -Selected Updates :: Journal Watch - Key articles and abstracts from 100+ peer-reviewed journals :: Week in Review A highly selective capture of strategic developments, research, commentary, analysis and announcements spanning Human Rights Action, Humanitarian Response, Health, Education, Holistic Development, Sustainable Resilience. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 09 September 2020 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Seelig, Frederik and Bezerra, Haroldo and Cameron, Mary and Hii, Jerey and Hiscox, Alexandra and Irish, Seth and Jones, Robert T. and Lang, Trudie and Lindsay, Steven W. and Lowe, Rachel and Nyoni, Tanaka Manikidza and Power, Grace M. and Quintero, Juliana and Stewart-Ibarra, Anna M. and Tusting, Lucy S. and Tytheridge, Scott and Logan, James G. (2020) 'The COVID-19 pandemic should not derail global vector control eorts.', PLoS neglected tropical diseases., 14 (8). e0008606. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008606 Publisher's copyright statement: This is an open access article, free of all copyright, and may be freely reproduced, distributed, transmitted, modied, built upon, or otherwise used by anyone for any lawful purpose. The work is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 public domain dedication. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details.