Designingfor Mod Development: User Creativity As Produci Development Strategy on the Firm- Hosted 3D Software Platform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Kulturelle Aneignung Des Spielraums. Vom Virtuosen Spielen

Alexander Knorr Die kulturelle Aneignung des Spielraums Vom virtuosen Spielen zum Modifizieren und zurück Ausgangspunkt Obgleich der digital divide immer noch verhindert, dass Computerspiele zu ge- nuin globalen Gütern werden, wie es etwa der Verbrennungsmotor, die Ka- laschnikow, Hollywoodikonen, Aspirin und Coca Cola längst sind, sprengt ihre sich nach wie vor beschleunigende Verbreitung deutlich geografische, natio- nale, soziale und kulturelle Schranken. In den durch die Internetinfrastruktur ermöglichten konzeptuellen Kommunikations- und Interaktionsräumen sind Spieler- und Spielkulturen wesentlich verortet, welche weiten Teilen des öf- fentlichen Diskurses fremd und unverständlich erscheinen, insofern sie über- haupt bekannt sind. Durch eine von ethnologischen Methoden und Konzepten getragene, lang andauernde und nachhaltige Annäherung ¯1 an transnational zusammengesetzte Spielergemeinschaften werden die kulturell informierten Handlungen ihrer Mitglieder sichtbar und verstehbar. Es erschließen sich so- ziale Welten geteilter Werte, Normen, Vorstellungen, Ideen, Ästhetiken und Praktiken – Kulturen eben, die wesentlich komplexer, reichhaltiger und viel- schichtiger sind, als der oberflächliche Zaungast es sich vorzustellen vermag. Der vorliegende Artikel konzentriert sich auf ein, im Umfeld prototypischer First-Person-Shooter – genau dem Genre, das im öffentlichen Diskurs beson- ders unter Beschuss steht – entstandenes Phänomen: Die äußerst performativ orientierte Kultur des trickjumping. Nach einer Einführung in das ethnologische -

HTTP Cookie - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 14/05/2014

HTTP cookie - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 14/05/2014 Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search HTTP cookie From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Navigation A cookie, also known as an HTTP cookie, web cookie, or browser HTTP Main page cookie, is a small piece of data sent from a website and stored in a Persistence · Compression · HTTPS · Contents user's web browser while the user is browsing that website. Every time Request methods Featured content the user loads the website, the browser sends the cookie back to the OPTIONS · GET · HEAD · POST · PUT · Current events server to notify the website of the user's previous activity.[1] Cookies DELETE · TRACE · CONNECT · PATCH · Random article Donate to Wikipedia were designed to be a reliable mechanism for websites to remember Header fields Wikimedia Shop stateful information (such as items in a shopping cart) or to record the Cookie · ETag · Location · HTTP referer · DNT user's browsing activity (including clicking particular buttons, logging in, · X-Forwarded-For · Interaction or recording which pages were visited by the user as far back as months Status codes or years ago). 301 Moved Permanently · 302 Found · Help 303 See Other · 403 Forbidden · About Wikipedia Although cookies cannot carry viruses, and cannot install malware on 404 Not Found · [2] Community portal the host computer, tracking cookies and especially third-party v · t · e · Recent changes tracking cookies are commonly used as ways to compile long-term Contact page records of individuals' browsing histories—a potential privacy concern that prompted European[3] and U.S. -

June 2019 the Edelweiss Am Rio Grande Nachrichten

Edelweiss am Rio Grande German American Club Newsletter-June 2019 1 The Edelweiss am Rio Grande Nachrichten The newsletter of the Edelweiss am Rio Grande German American Club 4821 Menaul Blvd., NE Albuquerque, NM 87110-3037 (505) 888-4833 Website: edelweissgac.org/ Email: [email protected] Facebook: Edelweiss German-American Club June 2019 Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kaffeeklatsch Irish Dance 7pm Karaoke 3:00 pm 5-7 See page 2 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 DCC Mtng & Irish Dance 7pm Strawberry Fest Dance 2-6 pm Essen und Dance See Pg 4 Sprechen pg 3 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Jazz Sunday GAC Board Irish Dance 7pm Karaoke Private Party 2:00-5:30 pm of Directors 5-7 6-12 6:30 pm 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Irish Dance 7pm Sock Hop Dance See Pg 4 30 2pm-German- Language Movie- see pg 3 Edelweiss am Rio Grande German American Club Newsletter-June 2019 2 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Summer is finally here and I’m looking forward to our Anniversary Ball, Luau, Blues Night and just rolling out those lazy, hazy, crazy days of Summer. On a more serious note there have been some misunderstandings between the GAC and one of our oldest and most highly valued associate clubs the Irish-American Society (IAS). Their President, Ellen Dowling, has requested, and I have extended an invitation to her, her Board of Directors, and IAS members at large to address the GAC at our next Board meeting. -

The Next Breathtaking Installment in The

v v THE NEXT BREATHTAKING INSTALLMENT IN THE #1 BESTSELLING AMULET SERIES HAS ARRIVED! FALL Cover 2018 illustration SCHOLASTIC Art © Dav Pilkey. DOG MAN and related designs are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Dav Pilkey. Dav of trademarks registered and/or trademarks designs are DOG MAN and related Pilkey. Art © Dav HARDCOVER & PAPERBACK BOOKS SCH OLASTIC HARDCOVER & PAPERBACK BOOKS & PAPERBACK HARDCOVER OLASTIC FALL 2018 See page 19! SCHOLASTIC Also available 3367548 Scholastic Canada Ltd. Please recycle this catalogue. 604 King St. West, Toronto, ON. M5V 1E1 1-800-268-3848 www.scholastic.ca Follow us: ScholasticCda ScholasticCanada ScholasticCda ScholasticCda ScholasticCda CELEBRATING 20 YEARS OF MISCHIEVOUS DAVID! A TIMELY, WHEN THERE’S TROUBLE, GUT-WRENCHING NOVEL YOU CAN BET FROM YA MASTER “DAVID DID IT!” KODY KEPLINGER. David Shannon’s beloved character is back, and up to his usual mischief… this time taunting In the aftermath of a school shooting, his older brother! six survivors grapple with loss, trauma, and the truth about that day. see pg 53 see pg 71 A POIGNANT AND MOVING Diary of a Wimpy Kid NEW YA MEMOIR FROM AWARD-WINNING James Bond meets with this new fully-illustratedMac Barnett! GRAPHIC NOVELIST JARRETT KROSOCZKA. chapter book series by Before Mac Barnett was an AUTHOR, “As with any honest memoir, the he was a KID. And while he was a KID, greatest challenge has been to write he was a SPY. with compassion about the people Not just any SPY. who hurt me greatly, and to write But a spy...for the QUEEN OF ENGLAND. with truth about the people I adore.” — Jarrett Krosoczka see pg 9 see pg 23 Scholastic Fall 2018 Catalogue Follow us: 2 Super Leads scholasticCDA ExcitingnewreadsfromJ.K.Rowling,DavPilkey, MacBarnett,ScottWesterfeldandmore! ScholasticCanada scholasticcda 17 Graphix Brandnewgraphicnoveladventures! scholasticcda 27 Chapter Book Series E-catalogues available at: CatchnewreleasesinthebestsellingGeronimoStilton, DragonMastersandOwlDiariesseries. -

Quake Three Download

Quake three download Download ioquake3. The Quake 3 engine is open source. The Quake III: Arena game itself is not free. You must purchase the game to use the data and play. While the first Quake and its sequel were equally divided between singleplayer and multiplayer portions, id's Quake III: Arena scrapped the. I fucking love you.. My car has a Quake 3 logo vinyl I got a Quake 3 logo tatoo on my back I just ordered a. Download Demo Includes 2 items: Quake III Arena, QUAKE III: Team Arena Includes 8 items: QUAKE, QUAKE II, QUAKE II Mission Pack: Ground Zero. Quake 3 Gold Free Download PC Game setup in single direct link for windows. Quark III Gold is an impressive first person shooter game. Quake III Arena GPL Source Release. Contribute to Quake-III-Arena development by creating an account on GitHub. Rust Assembly Shell. Clone or download. Quake III Arena, free download. Famous early 3D game. 4 screenshots along with a virus/malware test and a free download link. Quake III Description. Never before have the forces aligned. United by name and by cause, The Fallen, Pagans, Crusaders, Intruders, and Stroggs must channel. Quake III: Team Arena takes the awesome gameplay of Quake III: Arena one step further, with team-based play. Run, dodge, jump, and fire your way through. This is the first and original port of ioquake3 to Android available on Google Play, while commercial forks are NOT, don't pay for a free GPL product ***. Topic Starter, Topic: Quake III Arena Downloads OSP a - Download Aerowalk by the Preacher, recreated by the Hubster - Download. -

Being in Cyberspace

Virtually Real: Being In Cyberspace By Morgan Leigh A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania November, 2014 1 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of the my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Statement of Ethical Conduct The research associated with this thesis abides by the international and Australian codes on human and animal experimentation, the guidelines by the Australian Government's Office of the Gene Technology Regulator and the rulings of the Safety, Ethics and Institutional Biosafety Committees of the University. Morgan Leigh 7/11/2014 Authority of Access This thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/. You are free to: • Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material • for any purpose, even commercially. • The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following terms: • Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. -

Giant List of Web Browsers

Giant List of Web Browsers The majority of the world uses a default or big tech browsers but there are many alternatives out there which may be a better choice. Take a look through our list & see if there is something you like the look of. All links open in new windows. Caveat emptor old friend & happy surfing. 1. 32bit https://www.electrasoft.com/32bw.htm 2. 360 Security https://browser.360.cn/se/en.html 3. Avant http://www.avantbrowser.com 4. Avast/SafeZone https://www.avast.com/en-us/secure-browser 5. Basilisk https://www.basilisk-browser.org 6. Bento https://bentobrowser.com 7. Bitty http://www.bitty.com 8. Blisk https://blisk.io 9. Brave https://brave.com 10. BriskBard https://www.briskbard.com 11. Chrome https://www.google.com/chrome 12. Chromium https://www.chromium.org/Home 13. Citrio http://citrio.com 14. Cliqz https://cliqz.com 15. C?c C?c https://coccoc.com 16. Comodo IceDragon https://www.comodo.com/home/browsers-toolbars/icedragon-browser.php 17. Comodo Dragon https://www.comodo.com/home/browsers-toolbars/browser.php 18. Coowon http://coowon.com 19. Crusta https://sourceforge.net/projects/crustabrowser 20. Dillo https://www.dillo.org 21. Dolphin http://dolphin.com 22. Dooble https://textbrowser.github.io/dooble 23. Edge https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/microsoft-edge 24. ELinks http://elinks.or.cz 25. Epic https://www.epicbrowser.com 26. Epiphany https://projects-old.gnome.org/epiphany 27. Falkon https://www.falkon.org 28. Firefox https://www.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/new 29. -

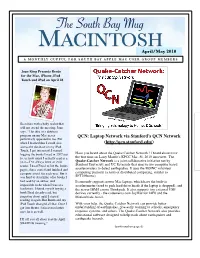

Apr/May SBAMUG/PIP Printing

The South Bay Mug MACINTOSH April/May 2010 A M O N T H L Y C U P F U L F O R S O U T H B A Y A P P L E M A C U S E R G R O U P M E M B E R S Joan King Presents Bento for the Mac, iPhone, iPod Touch and iPad on April 28 Seen here with a baby ocelot that will not attend the meeting, Joan says, “The idea of a database program on my Mac never QCN: Laptop Network via Stanford’s QCN Network particularly appealed to me. But when I learned that I could also (http://qcn.stanford.edu/) access the database on my iPod Touch, I got interested. I started logging the books I read in 2007 just Have you heard about the Quake Catcher Network? I heard about it for to see how much I actually read in a the first time on Larry Mantle’s KPCC Mar. 31, 2010 interview. The year—I’ve always been an avid Quake-Catcher Network is a joint collaborative initiative run by reader. I used Excel to list the books, Stanford University and UC Riverside that aims to use computer based pages, dates started and finished and accelerometers to detect earthquakes. It uses the BOINC volunteer compute a total for each year. But it computing platform (a form of distributed computing, similar to was hard to determine what books I SETI@home). had read by an author, and It currently supports newer Mac laptops which have the built-in impossible to do when I was at a accelerometer (used to park hard drive heads if the laptop is dropped), and bookstore. -

Loss of Hammer Throw Range Would Leave a Big Hole

Star power WEEKEND | 16 DECEMBER 15, 2017 VOLUME 25, NO. 47 www.MountainViewOnline.com 650.964.6300 MOVIES | 19 Ambitious North Bayshore plan wins council approval GUIDELINES FOR ADDING 9,850 HOMES NEAR GOOGLE GET UNANIMOUS SUPPORT By Mark Noack “We believe Mountain View will be making a material impact fter years of analysis, an on the imbalance between hous- ambitious plan to trans- ing and jobs,” said Mark Golan, Aform the tech develop- Google vice president of real ment in North Bayshore by add- estate. “We’re proud to call ing a dense, dynamic residential Mountain View our home, and neighborhood received its final we look forward to working with round of approvals from the City the city and other stakeholders.” Council on Tuesday night. More than any other entity, The strategy known as the Google will be a crucial partner North Bayshore Precise Plan in bringing the city’s precise plan calls for a spate of rapid and to fruition. About three years intense housing development ago, the company came around that is ultimately expected to to the idea of creating thousands MICHELLE LE bring 9,850 new apartments to of homes near its headquarters. Sophie Hitchon, an Olympic bronze medalist, watches her throw sail through the air at the hammer the doorstep of the city’s tech That support was motivated by throw practice site on Moffett Field. behemoth, Google. The plan the company’s own needs — lays out a vision for a new urban traffic and housing availability community where corporate tech had become major problems for Loss of hammer throw range workers could live, work, dine Google’s growing workforce. -

Get Set up for Today's Workshop

get set up for today’s workshop Please open the following in Firefox: 1. Poll: bit.ly/iuwim25 • Take a brief poll before we get started 2. Python: www.pythonanywhere.com • Create a free account • Click on Account à Add nbrodnax as a teacher (optional) • Click on Dashboard 3. Data: http://www.amstat.org/publications/jse/ • Journal of Statistics Education • On the left panel, click on Data Archive Introduction to Web Scraping with Python NaLette Brodnax Indiana University Bloomington School of Public & Environmental Affairs Department of Political Science Center of Excellence for Women in Technology CENTER OF EXCELLENCE FOR WOMEN IN TECHNOLOGY We started a conversation CEWiT addresses the global Faculty, staf, alumnae and about women in technology, need to increase participation of student alliances hold events, ensuring all women have a women at all stages of their host professional seminars, and seat at the table in every involvement in technology give IU women opportunities to technology venture. related fields. build a community. CONNECT WITH US iucewit @IU_CEWiT iucewit cewit.indiana.edu my goals • Get you involved • Demystify programming • Help you scrape some data Treat Teach yo’ self... your goals Please take the quick poll at: bit.ly/iuwim25 what is web scraping? Web scraping is a set of techniques for extracting information from the web and transforming it into structured data that we can store and analyze. complexity 1 2 3 static dynamic application webpage webpage programming interface (api) when should we scrape the web? Web -

Optimization of Display-Wall Aware Applications on Cluster Based Systems Ismael Arroyo Campos

Nom/Logotip de la Universitat on s’ha llegit la tesi Optimization of Display-Wall Aware Applications on Cluster Based Systems Ismael Arroyo Campos http://hdl.handle.net/10803/405579 Optimization of Display-Wall Aware Applications on Cluster Based Systemsí està subjecte a una llicència de Reconeixement 4.0 No adaptada de Creative Commons (c) 2017, Ismael Arroyo Campos DOCTORAL THESIS Optimization of Display-Wall Aware Applications on Cluster Based Systems Ismael Arroyo Campos This thesis is presented to apply to the Doctor degree with an international mention by the University of Lleida Doctorate in Engineering and Information Technology Director Francesc Giné de Sola Concepció Roig Mateu Tutor Concepció Roig Mateu 2017 2 Resum Actualment, els sistemes d'informaci´oi comunicaci´oque treballen amb grans volums de dades requereixen l'´usde plataformes que permetin una representaci´oentenible des del punt de vista de l'usuari. En aquesta tesi s'analitzen les plataformes Cluster Display Wall, usades per a la visualitzaci´ode dades massives, i es treballa concre- tament amb la plataforma Liquid Galaxy, desenvolupada per Google. Mitjan¸cant la plataforma Liquid Galaxy, es realitza un estudi de rendiment d'aplicacions de visu- alitzaci´orepresentatives, identificant els aspectes de rendiment m´esrellevants i els possibles colls d'ampolla. De forma espec´ıfica, s'estudia amb major profunditat un cas representatiu d’aplicaci´ode visualitzaci´o,el Google Earth. El comportament del sistema executant Google Earth s'analitza mitjan¸cant diferents tipus de test amb usuaris reals. Per a aquest fi, es defineix una nova m`etricade rendiment, basada en la ratio de visualitzaci´o,i es valora la usabilitat del sistema mitjan¸cant els atributs tradicionals d'efectivitat, efici`enciai satisfacci´o.Adicionalment, el rendiment del sis- tema es modela anal´ıticament i es prova la precisi´odel model comparant-ho amb resultats reals. -

Playing Quake III Arena for SEGA Dreamcast with Your Broadband Adapter

Playing Quake III Arena for SEGA Dreamcast with your Broadband Adapter Quake III Arena for SEGA Dreamcast supports the Dreamcast Dreamcast Users who also use PCs Broadband Adapter. In order to play Quake III Arena with your for High Speed Internet Access Dreamcast Broadband Adapter, you must have access to a high- Dreamcast Users who also use PCs for High Speed Internet Access speed network or Internet Service Provider (ISP) that uses either Static IP, DHCP, or PPP over Ethernet (PPPOE). Please check with If your PC is connected to the same high speed network that you your Service Provider if you are unsure if one of these protocols is would like to connect the Dreamcast to, follow these steps to get supported or, if you also have a PC and are using it for this same the information you need from your PC. Windows 95/98/ME users ISP, check the connection settings on your PC. can get information about their high speed network settings by: Dynamically Allocated IP Address (Using DHCP) 1) Go to the Start Menu and choose Run. 2) Type “winipcfg” and select OK. You must have the T CP/IP To connect to an ISP that uses DHCP, follow these steps: protocol installed on your PC to be able to use winipcfg. 1)Select the Internet Game option from the Mode Select Screen. Windows 2000 users can get information about their high speed 2) Leave your username and password blank. network settings by: 3)Make sure the IP Address, Gateway, Primary DNS, and Secondary DNS are all marked with “0.0.0.0”.