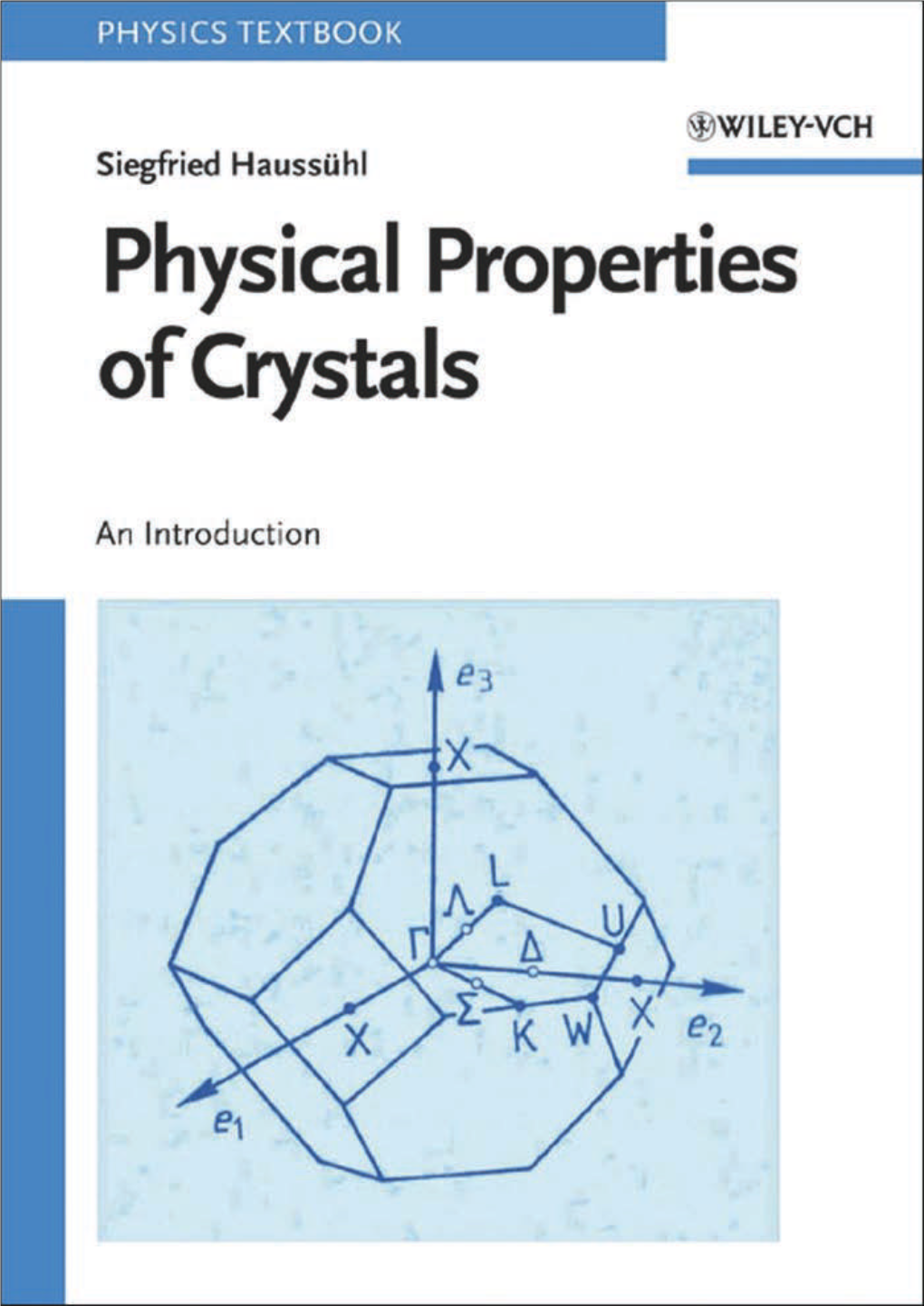

Siegfried Haussühl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Classifications-No Links

CLASSIFYING MINERALS Minerals are divided into nine (9) broad classifications. They are typically classified based on the negatively charged (anionic) portion of their chemical composition. For example, copper oxide (CuO) consists of copper (Cu ++ ) and oxygen (O -- ) ions, and the negatively charged oxygen ion puts it in the “Oxide” classification (which also includes iron oxide, titanium dioxide, etc). The classifications are: Silicate class The largest group of minerals by far, the silicates are mostly composed of silicon and oxygen, combined with ions like aluminum, magnesium, iron, and calcium. Some important rock-forming silicates include the feldspars, quartz, olivines, pyroxenes, garnets, and micas. Carbonate class 2− The carbonate minerals contain the anion (CO 3) . They are deposited in marine settings from accumulated shells of marine life and also in evaporitic areas like the Great Salt Lake and karst regions where they form caves, stalactites and stalagmites. Typical carbonates include calcite and aragonite (both calcium carbonate), dolomite (magnesium/calcium carbonate) and siderite (iron carbonate). The carbonate class also includes the nitrate and borate minerals. Sulfate class 2− Sulfate minerals all contain the sulfate anion, SO 4 . Sulfates commonly form in evaporitic settings where highly saline waters slowly evaporate, in hydrothermal vein systems as gangue minerals and as secondary oxidation products of original sulfide minerals. Common sulfates include anhydrite (calcium sulfate), celestine (strontium sulfate), barite (barium sulfate), and gypsum (hydrated calcium sulfate). The sulfate class also includes the chromate, molybdate, selenate, sulfite, tellurate, and tungstate minerals. Halide class The halide minerals form the natural salts and include fluorite (calcium fluoride), halite (sodium chloride) and sylvite (potassium chloride). -

A Vibrational Spectroscopic Study of the Silicate Mineral Harmotome Â

Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 137 (2015) 70–74 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/saa A vibrational spectroscopic study of the silicate mineral harmotome – (Ba,Na,K)1-2(Si,Al)8O16Á6H2O – A natural zeolite ⇑ Ray L. Frost a, , Andrés López a, Lina Wang a,b, Antônio Wilson Romano c, Ricardo Scholz d a School of Chemistry, Physics and Mechanical Engineering, Science and Engineering Faculty, Queensland University of Technology, GPO Box 2434, Brisbane, Queensland 4001, Australia b School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Tianjin University of Technology, No. 391, Bin Shui West Road, Xi Qing District, Tianjin, PR China c Geology Department, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG 31270-901, Brazil d Geology Department, School of Mines, Federal University of Ouro Preto, Campus Morro do Cruzeiro, Ouro Preto, MG 35400-00, Brazil highlights graphical abstract We have studied the mineral harmotome (Ba,Na,K)1- 2(Si,Al)8O16Á6H2O. It is a natural zeolite. Raman and infrared bands are attributed to siloxane stretching and bending vibrations. A sharp infrared band at 3731 cmÀ1 is assigned to the OH stretching vibration of SiOH units. article info abstract Article history: The mineral harmotome (Ba,Na,K)1-2(Si,Al)8O16Á6H2O is a crystalline sodium calcium silicate which has Received 31 March 2014 the potential to be used in plaster boards and other industrial applications. It is a natural zeolite with cat- Received in revised form 7 July 2014 alytic potential. Raman bands at 1020 and 1102 cmÀ1 are assigned to the SiO stretching vibrations of Accepted 28 July 2014 three dimensional siloxane units. -

Mineralogy and Origin of Coarse-Grained Segregations in the Pyrometallurgical Zn-Pb Slags from Katowice-Wełnowiec (Poland)

Miner Petrol DOI 10.1007/s00710-016-0439-1 ORIGINAL PAPER Mineralogy and origin of coarse-grained segregations in the pyrometallurgical Zn-Pb slags from Katowice-Wełnowiec (Poland) R. Warchulski1 & A. Gawęda 1 & J. Janeczek1 & M. Kądziołka-Gaweł2 Received: 20 December 2015 /Accepted: 9 March 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The unique among pyrometallurgical slags, coarse- Introduction grained (up to 2.5 cm) segregations (up to 40 cm long) rimmed by Baplitic^ border zones occur within holocrystalline histor- Pyrometallurgical slags from base-metal smelting have recent- ical Zn-smelting slag in Katowice, S Poland. Slag surrounding ly been studied extensively mainly with the purpose of the segregations consists of olivine, spinel series, melilite, assessing their environmental impact for many of them con- clinopyroxene, leucite, nepheline and sulphides. Ca-oliv- tain elevated concentrations of potentially toxic metals, in- ines, kalsilite and mica compositionally similar to cluding As, Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn (e.g. Ettler et al. 2001; oxykinoshitalite occur in border zones in addition to Puziewicz et al. 2007; Álvarez-Valero et al. 2009,Piatakand olivine, spinel series and melilite. Miarolitic and mas- Seal 2010; Vítková et al. 2010;Kierczaketal.2010;Ettlerand sive pegmatite-like segregations are built of subhedral Johan 2014). Those metals may be partitioned among phases crystals of melilite, leucite, spinel series, clinopyroxene with different leaching potential during weathering. and hematite. Melilite, clinopyroxenes and spinels in the Therefore, the detailed knowledge of phase composition of segregationsareenrichedinZnrelativelytooriginal slags is prerequisite for understanding their leaching behav- slag and to fine-grained border zones. -

Mottramite Pbcu(VO4)(OH) C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1 Crystal Data: Orthorhombic

Mottramite PbCu(VO4)(OH) c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Orthorhombic. Point Group: 2/m 2/m 2/m. As crystals, equant or dipyramidal {111}, prismatic [001] or [100], with {101}, {201}, many others, to 3 mm, in drusy crusts, botryoidal, usually granular to compact, massive. Physical Properties: Fracture: Small conchoidal to uneven. Tenacity: Brittle. Hardness = 3–3.5 D(meas.) = ∼5.9 D(calc.) = 6.187 Optical Properties: Transparent to nearly opaque. Color: Grass-green, olive-green, yellow- green, siskin-green, blackish brown, nearly black. Streak: Yellowish green. Luster: Greasy. Optical Class: Biaxial (–), rarely biaxial (+). Pleochroism: Weak to strong; X = Y = canary-yellow to greenish yellow; Z = brownish yellow. Orientation: X = c; Y = b; Z = a. Dispersion: r> v,strong; rarely r< v.α= 2.17(2) β = 2.26(2) γ = 2.32(2) 2V(meas.) = ∼73◦ Cell Data: Space Group: P nma. a = 7.667–7.730 b = 6.034–6.067 c = 9.278–9.332 Z=4 X-ray Powder Pattern: Mottram St. Andrew, England; close to descloizite. 3.24 (vvs), 5.07 (vs), 2.87 (vs), 2.68 (vs), 2.66 (vs), 2.59 (vs), 1.648 (vs) Chemistry: (1) (2) (1) (2) CrO3 0.50 ZnO 0.31 10.08 P2O5 0.24 PbO 55.64 55.30 As2O5 1.33 H2O 3.57 2.23 V2O5 21.21 22.53 insol. 0.17 CuO 17.05 9.86 Total 100.02 100.00 (1) Bisbee, Arizona, USA; average of three analyses. (2) Pb(Cu, Zn)(VO4)(OH) with Zn:Cu = 1:1. -

Descloizite Pbzn(VO4)(OH) C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1

Descloizite PbZn(VO4)(OH) c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Orthorhombic. Point Group: 2/m 2/m 2/m. As crystals, equant or pyramidal {111}, prismatic [001] or [100], or tabular {100}, with {101}, {201}, many others, rarely skeletal, to 5 cm, commonly in drusy crusts, stalactitic or botryoidal, coarsely fibrous, granular to compact, massive. Physical Properties: Fracture: Small conchoidal to uneven. Tenacity: Brittle. Hardness = 3–3.5 D(meas.) = ∼6.2 D(calc.) = 6.202 Optical Properties: Transparent to nearly opaque. Color: Brownish red, red-orange, reddish brown to blackish brown, nearly black. Streak: Orange to brownish red. Luster: Greasy. Optical Class: Biaxial (–), rarely biaxial (+). Pleochroism: Weak to strong; X = Y = canary-yellow to greenish yellow; Z = brownish yellow. Orientation: X = c; Y = b; Z = a. Dispersion: r> v,strong; rarely r< v.α= 2.185(10) β = 2.265(10) γ = 2.35(10) 2V(meas.) = ∼90◦ Cell Data: Space Group: P nma. a = 7.593 b = 6.057 c = 9.416 Z = 4 X-ray Powder Pattern: Venus mine, [El Guaico district, C´ordobaProvince,] Argentina; close to mottramite. 3.23 (vvs), 5.12 (vs), 2.90 (vs), 2.69 (vsb), 2.62 (vsb), 1.652 (vs), 4.25 (s) Chemistry: (1) (2) (1) (2) SiO2 0.02 ZnO 19.21 10.08 As2O5 0.00 PbO 55.47 55.30 +350◦ V2O5 22.76 22.53 H2O 2.17 −350◦ FeO trace H2O 0.02 MnO trace H2O 2.23 CuO 0.56 9.86 Total 100.21 100.00 (1) Abenab, Namibia. -

Heyite, Pbsfez(VO )Zo , a New Mineral from Nevada

MINERALOGICAL MAGAZINE, MARCH ~973, VOL. 39, PP. 65--68 Heyite, PbsFez(VO )zO , a new mineral from Nevada SIDNEY A. WILLIAMS Phelps Dodge Corporation, Douglas, Arizona SUMMARY. Heyite occurs in silicified limestone with other oxidation-zone minerals derived from galena, chalcopyrite, aod pyrite. The occurrence is near Ely, Nevada. Most common are pyro- morphite, cerussite, and chrysocolla. Heyite occurs on and replaces corroded tungstenian wulfenite. Crystals are small (up to o'4 mm), simple in habit, and monoclinic. Only {oo I }, {t oo}, {t I o}, and {io I } have been observed. Twinning on {I Io} is relatively common. The colour is yellow-orange with a yellow streak, H = 4. Electron probe analyses (average of three) gave PbO 75"4 %, ZnO o'8I %, FeO 8"4I %, V~O5 I2"65 %. This leads to Pbs(Fe,Zn)2(VO4)204, with Z = L The space group is P21/m. Cell constants, refined from powder data, are a 8-9IO/~, b 6'oi7, c 7"734 (all !o'oo4/~);/3 I I I ~ 53'-4-4'. The strongest powder lines (Cr-K~) are: 3"248, 11 ~, (i oo); 2"97o, 3oi, 21~, (69); 2"767, 2Ii (6I); 4"873, iio, (46); 3"674, ~I~, (35); 2"306 (33); 3"oio, o2o, (29); 3"4~2, 2o~, II~, (25); 8"281, Ioo, (25); and 2"II3 (2o). Geale 6'284, Gmeas 6"3• Optically biaxial with 2Ve 82~10, 89~e~ ; c~9 2-I85,/39 2'219, ~9 2.266; all values zko-oI and determined in S-Se melts. Dispersion is weak with p > v. -

Journal of the Russell Society, Vol 4 No 2

JOURNAL OF THE RUSSELL SOCIETY The journal of British Isles topographical mineralogy EDITOR: George Ryba.:k. 42 Bell Road. Sitlingbourn.:. Kent ME 10 4EB. L.K. JOURNAL MANAGER: Rex Cook. '13 Halifax Road . Nelson, Lancashire BB9 OEQ , U.K. EDITORrAL BOARD: F.B. Atkins. Oxford, U. K. R.J. King, Tewkesbury. U.K. R.E. Bevins. Cardiff, U. K. A. Livingstone, Edinburgh, U.K. R.S.W. Brai thwaite. Manchester. U.K. I.R. Plimer, Parkvill.:. Australia T.F. Bridges. Ovington. U.K. R.E. Starkey, Brom,grove, U.K S.c. Chamberlain. Syracuse. U. S.A. R.F. Symes. London, U.K. N.J. Forley. Keyworth. U.K. P.A. Williams. Kingswood. Australia R.A. Howie. Matlock. U.K. B. Young. Newcastle, U.K. Aims and Scope: The lournal publishes articles and reviews by both amateur and profe,sional mineralogists dealing with all a,pecI, of mineralogy. Contributions concerning the topographical mineralogy of the British Isles arc particularly welcome. Not~s for contributors can be found at the back of the Journal. Subscription rates: The Journal is free to members of the Russell Society. Subsc ription rates for two issues tiS. Enquiries should be made to the Journal Manager at the above address. Back copies of the Journal may also be ordered through the Journal Ma nager. Advertising: Details of advertising rates may be obtained from the Journal Manager. Published by The Russell Society. Registered charity No. 803308. Copyright The Russell Society 1993 . ISSN 0263 7839 FRONT COVER: Strontianite, Strontian mines, Highland Region, Scotland. 100 mm x 55 mm. -

Summer 1989 Gems & Gemology

VOLUME XXV SUMMER 1989 I The quarterly journal of the Gemological Institute of America SUMMER 1989 Volume 25 No. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 67 New Challenges for the Diamond Industry Richard T Liddicoat FEATURE 68 The Characteristics and Identification ARTICLES of Filled Diamonds John I. Koivula, Robert C. Kam~nerling, Emmanuel Fritsch, C. W Fryer, David Hargett, and Robert E. Kane NOTES , , , 84 A Preliminary Gemological Study of AND NEW Synthetic Diamond Thin Films TECHNIQUES Emmanuel Fritsch, Laurie Conner, and John I. Koivula Grading the Hope Diamond Robert Crowningshield Contribution to the Identification of Treated Colored Diamonds: Diamonds with Peculiar Color-Zoned Pavilions Emmanuel Fritsch and lames E. Shigley REGULAR 102 Gem Trade Lab Notes FEATURES 109 Editorial Forum 110 Gem News 119 Book Reviews 120 Gemological Abstracts ABOUT THE COVER: Fine diamonds in fine jewelry -like this superb necklace and matching earclips -represent the heart of the jewelry industry. Because of the premier importance of diamonds, however, the rewards of making a diamond "better" are potentially very great. Although historically there have been numerous diamond substitutes, modern technology has led to new industries devoted to the treatment of natural diamonds. Three of the articles in this issue deal with some of the most important-or potentially important-diamond treatments. The fourth deals with one of the world's most notorious untreated diamonds: the Hope. The necklace (97.75 ct total weight) and earclips (24.63 ct total weight) are courtesy of Van Cleef ed Arpels. Photo @ Harold e'J Erica Van Pelt - Photographers, Los Angeles, CA. Typesetting for Gems & Gemology is by Scientific Composition, Los Angeles, CA. -

Mottramite, Descloizite, and Vanadinite) in the Caldbeck Area of Cumberland

289 New occurrences of vanadium minerals (mottramite, descloizite, and vanadinite) in the Caldbeck area of Cumberland. By ART~VR W. G. KINGSBURu F.G.S., Dept. of Geology and Mineralogy, University Museum, Oxford, and J. HARTLnY, B.Sc., F.G.S., Dept. of Geology, University of Leeds. [Taken as read 10 June 1954.] Summary.--Four new occurrences of vanadium minerals are described. New X-ray powder data are given for descloizite and mottramite, and show appreciable differences. Evidence is brought that the original occurrence of mottramite was not at Mottram St. Andrew, Cheshire, but Pim Hill, Shropshire, and that most if not all specimens labelled Mottram St. Andrew or Cheshire really came from Pim Hill. ANADIUM minerals are rare in the British Isles, and only two V species, mottramite (Cu, Zn)PbV0tOH and vanadinite Pbs(VO4)aC1, have so far been recorded from a limited number of localities. We do not include the vanadiferous nodules from Budleigh Salterton in Devon, as the vanadiferous mineral has not been identified. Mottramite, supposedly from Mottram St. Andrew in Cheshire, was first described in 1876,1 but we have evidence (below, p. 293) that the locality was in fact Pim Hill in Shropshire. ~ Vanadinite has so far only been found at Leadhills and Wanlockhead in Scotland. Vauquelinite has been de- scribed from Leadhills and Wanlockhead,a but the specimens have since been shown to be mottramite. 4 As a result of our investigations in the Lake District, we have found several new localities in the Caldbeck area for raottramite, deseloizite, and vanadinite. Higher part of Brandy Gill, Carroek Fell. -

Proceedings of Annual Meeting Presentation Of

PROCEEDINGS OF ANNUAL MEETING 203 PRESENTATION OF PAPERS TEE PEGMATITES OF THE KEYSTONE AREA+ CONSTANTIN N. APSOURI Detailed mapping of the Hugo, Peerless, Dan Patch, Bob Ingersoll and lesser pegma- tites in the Keystone area, supported by critical study of the relations between their minerals and the country rock lead the writer to conclude that: (1) Some criteria interpreted as favoring replacement need revision, having been used to support two diametrically opposed views; examples are euhedral crystals. (2) Even a well-established criterion should be employed in the light of spatial and structural relations. (3) While replacement did take place, its role is over-emphasized. The spodumene "Iogs" at the Etta mine are not products of replacement. (4) The common belief that muscovite and muscovite books are replacement products is not supported by the field evidence cited by advocates of replacement. Muscovite forms less than 1/6 in common pegmatites. The contention that mica occurs at the contact is not strictly correct: mica books are frequently far from a major contact. Not all pegmatites bear mica. The almost constant association of schist xenoliths with an aureole of muscovite books suggests a genetic relationship. The mica probably resulted from the assimilation of the schist by the pegmatitic magma. (5) Structure and mode of emplacement of pegmatites has not been stressed lately. Pegmatites distend the country rock, or stope their way through, or both, as suggested by xenoliths and the sharp transgression of schistosity by some contacts. (6) The sequence of mineral paragenesis described by Landes (1928) is revised. (7) A single mapping of a pegmatite is insufficient. -

The Crystal Chemistry of Duftite, Pbcuaso4(OH)

Mineralogical Magazine, February 1998, Vol. 62(1), pp. 121–130 The crystalchemistry of duftite, PbCuAsO4(OH) and the b-duftiteproblem KHARISUN*, MAX R. TAYLOR, D. J. M BEVAN Department of Chemistry, The Flinders University of South Australia, GPOBox 2100 Adelaide, S.A.5001, Australia AND ALLAN PRING Department of Mineralogy, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, S.A.5000, Australia ABSTRACT Duftite,PbCu(AsO 4)(OH)is orthorhombic, space group P212121 with a = 7.768(1), b = 9. 211(1), c = 5.999(1) AÊ ,Z=4;the structure has been refined to R =4.6 % and Rw = 6.5% using640 observed reflections[F> 2 s(F)].The structure consists of chainsof edge-sharingCuO 6 ‘octahedra’,parallelto c; whichare linked via AsO 4 tetrahedraand Pb atoms in distorted square antiprismatic co-ordination to forma threedimensional network. The CuO 6 ‘octahedra’ showJahn-Teller distortion with the elongationrunning approximately along <627>. The hydrogen bonding network in the structure was characterizedusing bond valence calculations. ‘b-duftite’ isan intermediate in the duftite– conichalcite series,which has a modulatedstructure based on the intergrowth of the two structures in domains of approximately50 A Ê .Theorigin of the modulation is thought to beassociatedwith displacements in the oxygenlattice and is related to the orientation of the Jahn-Teller distortion of CuO 6 ‘octahedra’. Approximatelyhalf of the strips show an elongation parallel to <627> while the other strips are elongatedparallel to [010 ].This ordering results in an increase in the b cellrepeat compared to duftite andconichalcite. KEY WORDS: duftite,conichalcite, crystal structure, crystal chemistry, modulated structure. hadearlier tentatively proposed the point group Introduction 222,on the basis of morphological observations. -

A Specific Gravity Index for Minerats

A SPECIFICGRAVITY INDEX FOR MINERATS c. A. MURSKyI ern R. M. THOMPSON, Un'fuersityof Bri.ti,sh Col,umb,in,Voncouver, Canad,a This work was undertaken in order to provide a practical, and as far as possible,a complete list of specific gravities of minerals. An accurate speciflc cravity determination can usually be made quickly and this information when combined with other physical properties commonly leads to rapid mineral identification. Early complete but now outdated specific gravity lists are those of Miers given in his mineralogy textbook (1902),and Spencer(M,i,n. Mag.,2!, pp. 382-865,I}ZZ). A more recent list by Hurlbut (Dana's Manuatr of M,i,neral,ogy,LgE2) is incomplete and others are limited to rock forming minerals,Trdger (Tabel,l,enntr-optischen Best'i,mmungd,er geste,i,nsb.ildend,en M,ineral,e, 1952) and Morey (Encycto- ped,iaof Cherni,cal,Technol,ogy, Vol. 12, 19b4). In his mineral identification tables, smith (rd,entifi,cati,onand. qual,itatioe cherai,cal,anal,ys'i,s of mineral,s,second edition, New york, 19bB) groups minerals on the basis of specificgravity but in each of the twelve groups the minerals are listed in order of decreasinghardness. The present work should not be regarded as an index of all known minerals as the specificgravities of many minerals are unknown or known only approximately and are omitted from the current list. The list, in order of increasing specific gravity, includes all minerals without regard to other physical properties or to chemical composition. The designation I or II after the name indicates that the mineral falls in the classesof minerals describedin Dana Systemof M'ineralogyEdition 7, volume I (Native elements, sulphides, oxides, etc.) or II (Halides, carbonates, etc.) (L944 and 1951).