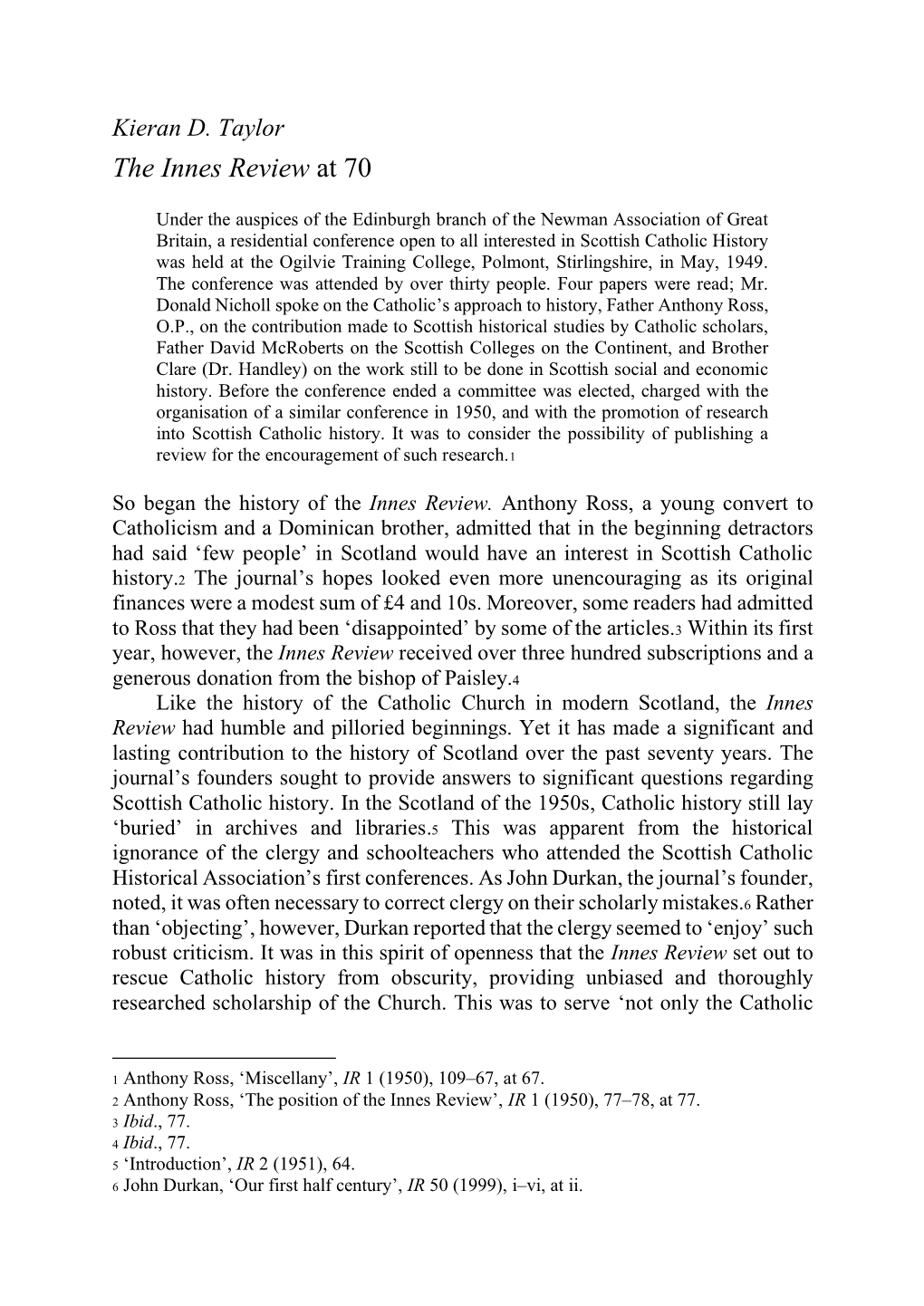

The Innes Review at 70

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

The Case of Michael Du Val's the Spanish English Rose

SEDERI Yearbook ISSN: 1135-7789 [email protected] Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies España Álvarez Recio, Leticia Pro-match literature and royal supremacy: The case of Michael Du Val’s The Spanish English Rose (1622) SEDERI Yearbook, núm. 22, 2012, pp. 7-27 Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies Valladolid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=333528766001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Pro-match literature and royal supremacy: The case of Michael Du Val’s The Spanish English Rose (1622) Leticia Álvarez Recio Universidad de Sevilla ABSTRACT In the years 1622-1623, at the climax of the negotiations for the Spanish-Match, King James enforced censorship on any works critical of his diplomatic policy and promoted the publication of texts that sided with his views on international relations, even though such writings may have sometimes gone beyond the propagandistic aims expected by the monarch. This is the case of Michael Du Val’s The Spanish-English Rose (1622), a political tract elaborated within court circles to promote the Anglo-Spanish alliance. This article analyzes its role in producing an alternative to the religious and imperial discourse inherited from the Elizabethan age. It also considers the intertextual relations between Du Val’s tract and other contemporary works in order to determine its part within the discursive network of the Anglican faith and political absolutism. -

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Traditional Marriage Left Exposed

POPE FRANCIS SCIAF looks NEW SERIES: calls on ahead at Harry Schnitker world to be the challenges explores Evan- peacemakers of 2014 gelii Gaudium Pages 6-7 Pages 10-11 Page 20 No 5550 VISIT YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER ONLINE AT WWW.SCONEWS.CO.UK Friday January 3 2014 | £1 Persecution of Christians must Traditional marriage left exposed stop, says Pope I MSPs reject provisos to protect religious freedoms, clergy and celebrants in new legislation POPE Francis used the feast of St Stephen, the Church’s first mar- By Ian Dunn tyr, to tell the world that discrimi- nation against Christians ‘must be SCOTTISH politicians have further eliminated.’ The Pope was speak- undermined the future of traditional ing on Boxing Day before pray- marriage ahead of voters deciding, ing the Angelus from his window this year, whether Scotland will overlooking St Peter’s Square. become independent. “Today we pray in a particular Over the festive period, MSPs refused way for Christians who undergo dis- to amend the Scottish Government’s crimination because of their witness same-sex ‘marriage’ legislation to protect to Christ and the Gospel,” he said. religious freedom, clergy and celebrants. “We are close to these brothers and In addition, the Scottish Government has sisters who, like St Stephen, are confirmed that tax breaks for married unjustly accused and made targets of couples would be scrapped in an inde- violence of various kinds. I am sure pendent Scotland. that, unfortunately, there are more of them today than in the early days of Religious freedom fears the Church. There are so many.” On the Tuesday before Christmas, the The Pope said that Christians face Scottish Parliament’s Equal Opportuni- discrimination in every part of the ties Committee voted against proposed world.“This [persecution] happen changes to the Marriage and Civil Part- especially where religious liberty is nership (Scotland) Bill by SNP and not yet guaranteed and fully realised,” Labour members that were aimed at he said. -

Thomas Pope Blount and the Scope of Early Modern Learning

Canon before Canon, Literature before Literature: Thomas Pope Blount and the Scope of Early Modern Learning Kelsey Jackson Williams abstract Sir Thomas Pope Blount (1649–1697), an English essayist and country gentleman, published two major literary biobibliographies, Censura celebriorum authorum (1690) and De re poetica (1694). In this essay, Kelsey Jackson Williams discusses the texts within the genre of historia literaria and contemporary under- standings of literature. In doing so, he engages with current debates surrounding canon formation and the shifts in disciplinary boundaries that followed in the wake of the Battle of the Books. Early modern canons and definitions of “literature” dif- fered radically from their modern equivalents, and a close reading of Blount’s work offers a window onto this forgotten literary landscape. keywords: historia liter- aria; biobibliography; Battle of the Books; John Locke; development of literary canon john locke’s library has long been recognized as a site of extensive anno- tation, commonplacing, and organization.1 In particular, Locke interleaved Thomas Hyde’s 1674 catalogue of the Bodleian Library and, using his own system of shelf marks, re-created it as an inventory of his own collection.2 Less well known are Locke’s annotations in another product of late seventeenth-century scholarship, Thomas Pope Blount’s 1690 Censura celebriorum authorum.3 The Censura contains brief biographies 1. John R. Harrison and Peter Laslett, The Library of John Locke, 2nd ed. (Oxford, 1971); G. G. Meynell, “John Locke’s Method of Common-placing, as Seen in His Drafts and His Medical Notebooks, Bodleian MSS Locke d. 9, f. -

Aspects Ofscottish Lesbian and Gay Activism, 1968 to 1992

THON WEY Aspects ofScottish lesbian and gay activism, 1968 to 1992 By Brian Dempsey Abstract The following paper charts the political campaign history of Scottish Lesbian and Gay activists over approximately two decades. It pays particular reference to organisations such as the Scottish Minorities Group (1969-78) and its successor, the Scottish Homosexual Rights Group (1978-92). These self organised Lesbian and Gay groups - which continue today as Outright Scotland - represented an unusual, and often anomalous, continuity as they frequently worked alongside rather more short-lived groups. Material fTom the Outright archives, SMG/SHRG publications and interviews with activists will be utilised to illustrate the changing aims and tactics of these groups over the period under consideration. CONTENTS PREFACE Page 1 INTRODUCTION Page 3 THE EARLY YEARS Page 6 Before 1969 ... The Batchelor Clan ... Setting up SMG ... The carly work ofSMG. GROUPS OTHER THAN SMG/SHRG Page 9 The Gay Lihcration Front ... Scanish Lesbian Feminists ... Radical Gay Men's Group ,.. Scottish Gay Activist Alliance ... Trade Union Group for Gay Rights ... Labour Campaign for Lesbian & Gay Rights Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners ... Student Lesbian and Gay Soci~tics ... others. LEGAL MATTERS Page 13 Dccriminalisation of male homosexual acts ... Strasbourg ... Employment ... Other legal work. MINORITIES WITHIN SMG Page 20 Women ... Black people .. young people. THE SEXUAL DIASPORA Page 22 Transvestites and Transsexuals ... Pederasts ... Bisexuals. SMG/SHRG "OFFSHOOTS" Page 24 Gay Switchboards and Lesbian Lines ... Gay Scotland. Lavender Menace/West & Wilde ... Scottish Aids Monitor. CONCLUSION Page 27 NOTES Page 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY Page 30 ABBREVIATIONS Page 32 PREFACE This paper brings together the history of lesbian and gay activism in Scotland for the first time. -

Spurlock, R.S. (2012) the Laity and the Structure of the Catholic Church in Early Modern Scotland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten: Publications Spurlock, R.S. (2012) The laity and the structure of the Catholic Church in early modern Scotland. In: Armstrong, R. and Ó hAnnracháin, T. (eds.) Insular Christianity. Alternative models of the Church in Britain and Ireland, c.1570–c.1700. Series: Politics, culture and society in early modern Britain . Manchester University Press, Manchester, UK, pp. 231-251. ISBN 9780719086984 Copyright © 2012 Manchester University Press A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/84396/ Deposited on: 28 January 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk . Insular Christianity Alternative models of the Church in Britain and Ireland, c.1570–c.1700 . Edited by ROBERT ARMSTRONG AND TADHG Ó HANNRACHÁIN Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Macmillan Armstrong_OHannrachain_InsChrist.indd 3 20/06/2012 11:19 Copyright © Manchester University Press 2012 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors, and no chapter may be reproduced wholly -

THE MANNERS of MY TIME When the Castle and the Cathedral Were Built

T HE M A NNE RS OF M Y TIM E \ 8K c ; HA W K INS DE M PS TER “ A UTHOR OF T HE M ARITI M E ALPS AND THE I R ’ S E ABOA anf E Tc . é’ c /6\ Q LONDON GR NT RI CHA RD S L TD A . ’ S T M A RTI N S STR E ET M DCCCCXX PRI NT E D IN GRE A T B R IT A IN I V T H. RIVE RS IDE PR E SS L IMIT E D E D IN B URG H DEDI CAT ED MY S IS T E R HE LE N I d o not know how old Ulysses may have been “ wh e n he boaste d that h e had se e n the m ann ers ” s ha h s t a of his tim e . I s u pect t t t i s fir of gre t t a e e s st ha e b ee e an that he h ad r v ll r mu v n ld erly, d “ a s s ffe e a sea- ch an e as ch as he was l o u r d g , in mu on h e at as t ec s e b his d o . only, turn ing om l , r ogni d y g am se e t - e h ea s a e and th s I v n y ig t y r of g , in i t h e can la c a t o ha see wilig t of lif I y l im ving n , in ffe e at t u es a a a t th e a e s di r nt l i d , f ir moun of m nn r , and th e a t of a e s m t e . -

Lives of Eminent Men of Aberdeen

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 08253730 3 - - j : EMINENT MEN OF ABERDEEN. ABERDEEN: PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, BY D. CHALMERS AND CO. LIVES OF EMINENT MEN OF ABERDEEN. BY JAMES BRUCE ABERDEEN : L. D. WYLLIE & SON S. MACLEAN ; W. COLLIE ; SMITH ; ; AND J. STRACHAN. W. RUSSEL ; W. LAURIE ; EDINBURGH: WILLIAM TAIT ; GLASGOW: DAVID ROBERTSON; LONDON : SMITH, ELDER, & CO. MDCCCXLI. THE NEW r TILDEN FOUr R 1, TO THOMAS BLAIKIE, ESQ., LORD PROVOST OF ABERDEEN, i's Folum? IS INSCRIBED, WITH THE HIGHEST RESPECT AND ESTEEM FOR HIS PUBLIC AND PRIVATE CHARACTER, AND FROM A SENSE OF THE INTEREST WHICH HE TAKES IN EVERY THING THAT CONCERNS THE HONOUR AND WELFARE OF HIS NATIVE CITY, BY HIS MUCH OBLIGED AND MOST OBEDIENT SERVANT, JAMES BRUCE. A 2 CONTENTS PAGE. ( JOHN BARBOU'R . 1 BISHOP ELPHINSTONE 22 BISHOP GAVIN DUXBAR . .57 DR. THOMAS MORISON . 76 GILBERT GRAY . 81 BISHOP PATRICK FORBES . 88 DR. DUNCAN LIDDEL . .115 GEORGE JAMIESON . 130 BISHOP WILLIAM FORBES . 152 DR. ARTHUR JOHNSTON . 171 EDWARD RABAN ... .193 DR. WILLIAM GUILD . 197 ALEXANDER ROSS . 225 GEORGE DALGARNO . 252 JOHN SPALDING . .202 HENRY SCOUGAL . 270 ROBERT GORDON . 289 PRINCIPAL BLACKWELL 303 ELIZABETH BLACKWELL . 307 DR. CAMPBELL . .319 DR. BEATTIE . 305 DR. HAMILTON . 3*1 DR. BROWN . 393 PREFACE IN offering this volume to the public, the writer trusts, that, with all its imperfections, it will be found not uninteresting to his townsmen, or, perhaps, to the general reader. At least it had frequently occurred to him, that an amusing and instructive book might be made on the subject which he has handled. -

Scholars and Literati at the University of Bologna (1088–1800)

Repertorium Eruditorum Totius Europae - RETE (2021) 1:1–10 1 https://doi.org/10.14428/rete.v1i0/Bologna Licence CC BY-SA 4.0 Scholars and Literati at the University of Bologna (1088–1800) David de la Croix Mara Vitale IRES/LIDAM, UCLouvain This note is a summary description of the set of scholars and literati who taught at the University of Bologna from its inception in the 11th century to the eve of the Industrial Revolution (1800). 1 The University The University of Bologna is one of the oldest academic institutions in the Western World and the rst to use the term universitas to dene a community of students and masters. Founded in 1088 by an organised guild of students who chose and nanced their teachers, the studium established its reputation as a place where research could be developed independently of religious and secular power (Rashdall 1895). Among the several studies devoted to the history of the University, the most important are the Sorbelli and Simeoni’s "Storia dell’Università di Bologna" (1940), and the book "Alma Mater Studiorum. L’università di Bologna nella storia della cultura e della civiltà" by the historian Calcaterra (1948). Both these works retrace the main events and portray the most important gures of the history of the university, from its foundation to 1888. 2 Sources The book by Mazzetti (1847) is the largest and most complete compilation of professors and intel- lectuals who have taught at the University of Bologna from its foundation until the rst half of the 19th century. The author traces short biographies, sorted in alphabetical order, enriched with anec- dotes about the private and academic life of the professors. -

Notes and References

NOTES AND REFERENCES INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF A SCOTTISH IDENTITY 1. The New Testament in Scots, traos. W. L. Lorimer (1983); rev. edn (London, 1985). There were a number of earlier translations, one by Murdoch Nisbet produced around 1520, but not printed till 1901-5, and several in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For details, see Graham Tulloch, A History of the Scots Bible (Aberdeen, 1989). 2. Marinell Ash, The Strange Death of Scottish History (Edinburgh, 1980), p. 151. 1 THE IDENTITY OF PLACE 1. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, traos. G. N. Garmonsway (London & New York, 1953), p. 82 (AD 891). The Anglo-Saxon text reads Scottas. 2. Graham and Anna Ritchie, Scotland: Archaeology and Early History (Edinburgh, 1991), pp. 89-94. 3. Ibid., p. 124. 4. Ibid., pp. 149-50. 5. A. P. Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men (London, 1984), pp. 43-5. 6. Venerabilis Baedae Historiam Ecclesiasticam Gentis A ngloru m, ed. C. Plummer (Oxford, 1896), I, p. 133 (Bk 3, ch. 4); but see A. A. M. Duncan, Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom (Edinburgh, 1975), pp. 46, 69-70. 7. Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men, p. 63 8. I have drawn here on ideas put forward by Dr Dauvit Broun in a paper on 'Defining Scotland before the Wars of Independence', given at the 1994 conference of the Association of Scottish 138 Notes and References Historical Studies, of which a text was included in the circulated conference papers. 9. Regesta Regum Scottorum, 11, ed. G. W. S. Barrow with W. W. Scott (Edinburgh, 1971), no. 61. -

June 1987 Department of Theology and Church History Q Kenneth G

HOLY COMMUNION IN THE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A Thesis submitted to the University of Glasgow for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy KENNETH GRANT HUGHES IFaculty of Divinity, June 1987 Department of Theology and Church History Q Kenneth G. Hughes 1987 i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to record my indebtedness to the late Rev. Ian A. Muirhead, M. A., B. D., formerly lecturer in the Department of Ecclesiastical History in the University of Glasgow, who guided my initial studies relating to the subject of this thesis. I am particularly conscious, also, of my special debt to his successor, Dr. Gavin White, who accepted me as one of his research students without demur and willingly gave time and consideration in guiding the direction of my writing and advising me in the most fruitful deployment of the in- formation at my disposal. The staff of the University Library, Glasgow, have been unfailingly helpful as have the staff of the Library of New College, Edinburgh. Mr. Ian Hope and Miss Joyce Barrie of that Library have particularly gone out of their way to assist in my search for elusive material. I spent a brief period in Germany searching for docu- mentary evidence of Scottish-students of divinity who matric- ulated at the universities of Germany and, again, I wish to acknowledge the help given to me by the Librarians and their staffs at the University Libraries of Heidelberg and Ttbingen. My written enquiries to Halle, Erlangen, Marburg, Giessen, G6ttingen and Rostock met with a most courteous response, though only a small amount of the interesting material they provided was of use in this present study.