22 Barbie in a Meat Dress: Performance and Mediatization in the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hat Magazine Archive Issues 1 - 10

The Hat Magazine Archive Issues 1 - 10 Issue No Date Main Articles Workroom Process ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 1 Apr-Jun 1999 Luton - Ascot Shoot - Sean Barratt Feathers - Dawn Bassam -Trade Shows - Fashion Museums & Dillon Wallwork ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 2 Jul-Sep 1999 Paris – Marie O’Regan – Royal Ascot Working with crinn with - Student Shows – Geoff Roberts Frederick Fox ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 3 Oct-Nov 1999 Hat Designer of the Year ’99 - Block Making with Men in Hats, shoot – Trade Fairs Serafina Grafton-Beaves ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 4 Jan-Mar 2000 Mitzi Lorenz – Philip Treacy couture Working with sinamay (1) show Paris – Florence – Bridal shoot with Marie O’Regan Street page – Trades Shows ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 5 Apr-Jun 2000 Coco Chanel – Trade Fairs Working with sinamay (2) Dagmara Childs – Knits Shoot with Marie O’Regan Street page - Trade Shows ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Issue 6 Jul-Sep 2000 Luton shoot – Royal Ascot Working with -

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE KEYS OF CHRISTMAS David Meyers YouTube Red Feature OPENING NIGHTS Isaac Rentz Dark Factory Entertainment Feature Los Angeles Film Festival G.U.Y. Lady Gaga Rocket In My Pocket / Riveting Short Film Entertainment MR. HAPPY Colin Tilley Vice Short Film COMMERCIALS & MUSIC VIDEOS SOL Republic Headphones, Kraken Rum, Fox Sports, Wendy’s, Corona, Xbox, Optimum, Comcast, Delta Airlines, Samsung, Hasbro, SONOS, Reebok, Veria Living, Dropbox, Walmart, Adidas, Go Daddy, Microsoft, Sony, Boomchickapop Popcorn, Macy’s Taco Bell, TGI Friday’s, Puma, ESPN, JCPenney, Infiniti, Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday Perfume, ARI by Ariana Grande; Nicki Minaj - “The Boys ft. Cassie”, Lil’ Wayne - “Love Me ft. Drake & Future”, BOB “Out of My Mind ft. Nicki Minaj”, Fergie - “M.I.L.F.$”, Mike Posner - “I Took A Pill in Ibiza”, DJ Snake ft. Bipolar Sunshine - “Middle”, Mark Ronson - “Uptown Funk”, Kelly Clarkson - “People Like Us”, Flo Rida - “Sweet Spot ft. Jennifer Lopez”, Chris Brown - “Fine China”, Kelly Rowland - “Kisses Down Low”, Mika - “Popular”, 3OH!3 - “Back to Life”, Margaret - “Thank You Very Much”, The Lonely Island - “YOLO ft. Adam Levine & Kendrick Lamar”, David Guetta “Just One Last Time”, Nicki Minaj - “I Am Your Leader”, David Guetta - “I Can Only Imagine ft. Chris Brown & Lil’ Wayne”, Flying Lotus - “Tiny Tortures”, Nicki Minaj - “Freedom”, Labrinth - “Last Time”, Chris Brown - “She Ain’t You”, Chris Brown - “Next To You ft. Justin Bieber”, French Montana - “Shot Caller ft. Diddy and Rick Ross”, Aura Dione - “Friends ft. Rock Mafia”, Common - “Blue Sky”, Game - “Red Nation ft. Lil’ Wayne”, Tyga “Faded ft. -

A King Named Nicki: Strategic Queerness and the Black Femmecee

Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory ISSN: 0740-770X (Print) 1748-5819 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwap20 A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee Savannah Shange To cite this article: Savannah Shange (2014) A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee, Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 24:1, 29-45, DOI: 10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 Published online: 14 May 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2181 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rwap20 Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 2014 Vol. 24, No. 1, 29–45, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee Savannah Shange* Department of Africana Studies and the Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States This article explores the deployment of race, queer sexuality, and femme gender performance in the work of rapper and pop musical artist Nicki Minaj. The author argues that Minaj’s complex assemblage of public personae functions as a sort of “bait and switch” on the laws of normativity, where she appears to perform as “straight” or “queer,” while upon closer examination, she refuses to be legible as either. Rather than perpetuate notions of Minaj as yet another pop diva, the author proposes that Minaj signals the emergence of the femmecee, or a rapper whose critical, strategic performance of queer femininity is inextricably linked to the production and reception of their rhymes. -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Jonah Lyrics

hold on ft. Curt Anderson produced & mixed by Pete Stewart for 4th Wall Music written by: J. Sorrentino, P. Stewart, C. Anderson Songs From The Fourth Wall (BMI) keep it beating music (SESAC) KJ52 Music (ASCAP) Hold on you got this don’t throw it away learn to forgive but don’t forget even when it feels like the worst hold on you got this don’t throw it away make more memories than regrets if nothing else just live and learn what if I was talking to the younger me way back when i was 3 running up and down the street not a thing i’ll ever need no shoes up my feet sitting in the puddle causing trouble for my family i would say get ready things are about to change I would say hold steady even if you run away i would say nobody knows what you about to face but i would say oh buddy hold for a better day you got them teachers all up on your case watching it just slip away feeling like it never changed now you feeling like you so deranged staring out the window where nobody seems to knows ya pain help now is on it’s way God know what you face wipe all the tears away let go of all the hate its all about to change know there’s a better way roll w/ the punches you can hold for a better day Hold on you got this don’t throw it away learn to forgive but don’t forget even when it feels like the worst hold on you got this don’t throw it away make more memories than regrets if nothing else just live and learn What if I was taking to the younger me 13 with the shirt clean and some dungarees Acid wash ripped jeans stripe like a bumblebee Running from the -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

Show Code: #12-50 Show Date: Weekend of December 8-9, 2012 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg

Show Code: #12-50 Show Date: Weekend of December 8-9, 2012 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg. 1 Content: #40 “REMEMBER WHEN (PUSH REWIND)” – Chris Wallace #39 “SOMEBODY THAT I USED TO KNOW” – Gotye #38 “OATH” – Cher Lloyd f/Becky G. Commercials: :30 Pier One :30 Barnes & Noble :30 Toys R Us :30 State Farm Auto Outcue: “...to a better state.” Segment Time: 14:02 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 2 Content: #37 “READY OR NOT” – Bridgit Mendler #36 “WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN” – Rihanna #35 “CATCH MY BREATH” – Kelly Clarkson #34 “ANYTHING COULD HAPPEN” – Ellie Goulding Commercials: :30 Subway/Fresh Buzz :30 Zazzle.com :30 Coca-Cola :30 Pier One Outcue: “...Pier One Imports.” Segment Time: 18:38 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 3 Content: #33 “TITANIUM” – David Guetta f/Sia Break Out: “BAD FOR ME” – Megan & Liz Extra: “SCREAM” – Usher #32 “DON'T STOP THE PARTY” – Pitbull f/TJR #31 “HALL OF FAME” – The Script f/will.i.am Commercials: :30 Telestrations :30 State Farm Auto Outcue: “...to a better state.” Segment Time: 19:20 Local Break 1:00 Seg. 4 ***This is an optional cut - Stations can opt to drop song for local inventory*** Content: AT40 Extra: “BOYFRIEND” – Justin Bieber Outcue: “…Seacrest on Twitter.” (sfx) Segment Time: 3:23 Hour 1 Total Time: 60:23 END OF DISC ONE Show Code: #12-50 Show Date: Weekend of December 8-9, 2012 Disc Two/Hour Two Opening Billboard None Seg. 1 Content: #30 “WIDE AWAKE” – Katy Perry #29 “LIVE WHILE WE'RE YOUNG” – One Direction #28 “50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE” – Train Commercials: :30 Subway/Fresh Buzz :30 Toys R Us :30 Atlantic/Wiz Khalifa :30 Zazzle.com Outcue: “...code holiday magic.” Segment Time: 13:44 Local Break 2:00 Seg. -

Why Hip-Hop Is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music

Why Hip-Hop is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez Advisor: Dr. Irene Mata Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies May 2013 © Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 “These Are the Breaks:” Flow, Layering, Rupture, and the History of Hip-Hop 6 Hip-Hop Identity Interventions and My Project 12 “When Hip-Hop Lost Its Way, He Added a Fifth Element – Knowledge” 18 Chapter 1. “Baby I Ride with My Mic in My Bra:” Nicki Minaj, Azealia Banks and the Black Female Body as Resistance 23 “Super Bass:” Black Sexual Politics and Romantic Relationships in the Works of Nicki Minaj and Azealia Banks 28 “Hey, I’m the Liquorice Bitch:” Challenging Dominant Representations of the Black Female Body 39 Fierce: Affirmation and Appropriation of Queer Black and Latin@ Cultures 43 Chapter 2. “Vamo a Vence:” Las Krudas, Feminist Activism, and Hip-Hop Identities across Borders 50 El Hip-Hop Cubano 53 Las Krudas and Queer Cuban Feminist Activism 57 Chapter 3. Coming Out and Keepin’ It Real: Frank Ocean, Big Freedia, and Hip- Hop Performances 69 Big Freedia, Queen Diva: Twerking, Positionality, and Challenging the Gaze 79 Conclusion 88 Bibliography 95 3 Introduction In 1987 Onika Tanya Maraj immigrated to Queens, New York City from her native Trinidad and Tobago with her family. Maraj attended a performing arts high school in New York City and pursued an acting career. In addition to acting, Maraj had an interest in singing and rapping. -

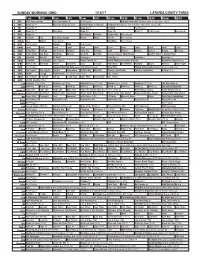

Sunday Morning Grid 1/15/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/15/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Football Night in America Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Kansas City Chiefs. (10:05) (N) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Program Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Planet Weird DIY Sci Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Miranda Age Fix With Dr. Anthony Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Escape From New York ››› (1981) Kurt Russell. -

Persona, Narrative, and Late Style in the Mourning of David Bowie on Reddit

Persona Studies 2020, vol. 6, no. 1 THE BLACKSTAR: PERSONA, NARRATIVE, AND LATE STYLE IN THE MOURNING OF DAVID BOWIE ON REDDIT SAMIRAN CULBERT NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT This article considers how David Bowie’s last persona, The Blackstar, framed his death through the narratives of mourning it provoked on the social media site Reddit. The official media narratives of death and the unofficial fan narratives of death can contradict each other, with fans usually bringing their own lived experiences to the mourning process. David Bowie is a performer of personas. While Bowie died in 2016, his personas have continued to live on, informing his legacy, his work, and his death reception. Through the concepts of persona, narrative, authenticity, late style, and mourning, this article finds that Bowie’s Blackstar persona actively constructs fan’s interaction with Bowie’s death. Instead of separate and contradicting narratives, this article finds that users on Reddit underpin and extend the media narrative of his death, using Bowie’s persona as a way to construct and establish their own mourning. As such, Bowie’s last persona is further entrenched as one of authentic mourning, of a genius constructing his own passing. With these narratives, fans construct their own personas, informing how they too would like to die: artistically and with grace. KEY WORDS Persona; Mourning; David Bowie; Late Style; Narrative; Reddit INTRODUCTION The Blackstar persona presented by Bowie in his last album and singles helped structure his fans’ mourning process. These last acts of artistry offered fans something to attach their mourning onto, allowing for them to work through their own mourning via Bowie’s presentation of his own death. -

Media Guide 1 Contents

Tuesday 19th - Saturday 23rd June 2018 MEDIA GUIDE 1 CONTENTS WELCOME TO ROYAL ASCOT FROM HER MAJESTY’S REPRESENTATIVE 4 VISITOR INFORMATION 5 RACING AT ROYAL ASCOT 6 RECORD PRIZE MONEY OF £13.45 MILLION AT ASCOT IN 2018 7 ROYAL ASCOT 2017 REVIEW 8 ROYAL ASCOT 2018 ORDER OF RUNNING AND PRIZE MONEY 10 ROYAL ASCOT GROUP I ENTRIES 12 A GLOBAL EVENT: ROYAL ASCOT’S RACE PROGRAMME MILESTONES 14 THE WEATHERBYS HAMILTON STAYERS’ MILLION 16 FOUR BREEDERS’ CUP CHALLENGE RACES TO BE HELD AT ROYAL ASCOT IN 2018 17 WORLD HORSE RACING LAUNCHES THE ULTIMATE DIGITAL RACING EXPERIENCE 18 CUSTOMERS INVITED TO BET WITH ASCOT 19 2018 GOFFS LONDON SALE GIVEN A NEW LOOK AT SAME ADDRESS 20 THE ROAD TO QIPCO BRITISH CHAMPIONS DAY 21 THE BELL ÉPOQUE 22 VETERINARY FACILITIES, EQUINE AND JOCKEYS’ FACILITIES 26 CHRIS STICKELS, CLERK OF THE COURSE 27 BROADCASTERS AT ROYAL ASCOT 28 NEW AT ROYAL ASCOT 30 COMMONWEALTH FASHION EXCHANGE 31 ASCOT RACECOURSE SUPPORTS 32 SCULPTURES 34 SHOPPING: THE COLLECTION 39 PARTNERS & SUPPLIERS 42 ASCOT’S OFFICIAL PARTNERS 43 ASCOT’S OFFICIAL SPONSORS AND SUPPLIERS 46 FASHION & DRESS CODE 50 ASCOT LAUNCHES THE SEVENTH ANNUAL ROYAL ASCOT STYLE GUIDE 51 THE HISTORY OF FASHION AT ROYAL ASCOT - KEY DATES 52 THE ROYAL ASCOT MILLINERY COLLECTIVE 2018 54 ROYAL ASCOT DRESS CODE 56 FINE DINING AT ROYAL ASCOT 58 FINE DINING AT ROYAL ASCOT CONTINUES TO DIVERSIFY AND DELIGHT 59 ASCOT HISTORY 66 ASCOT STORIES AND OTHER PROMOTIONAL FILMS 67 ROYAL ASCOT - THE ROYAL PROCESSION 68 THE BOWLER HAT AND ASCOT 71 ROYAL ASCOT FACTS AND FIGURES 72 ASCOT RACECOURSE -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.