Thesis-By-Monte-Holsinger.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CITY of JAYAWARDENA KOTTE: Mstory, FORM and FUNCTIONS.*

THE CITY OF JAYAWARDENA KOTTE: mSTORY, FORM AND FUNCTIONS.* See friend, proud city of Jayawardena, Renowned by victories achieved, Outvying the city of the gods in luxury, Where live rich folk who adore the triple gem with faith. Salalihini Sandesa Introduction The city of Jayawardena Kotte followed the inevitable pattern of a typical defence city. It emerged due to the needs of a critical era in history, attained its zenith under a powerful ruler and receded into oblivion when its defence mechanism and the defenders were weak. The purpose of Jb.is essay is to understand this pattern with emphasis on its form and functions. In the latter respect the essay differs from the writings on Kotte by G.P. V. Somaratna' and C.R. de Silva." whose primary attention was on the political history of the city. It also differs from the writings of E.W. Perera," D.O. Ranasinghe," C.M. de Alwis' and G.S. Wickramasuriya,? whose interest was mainly the archaeological remains of the city, its architecture and the preservation of its ruins. * An earlier draft of this paper was presented at the 12th Conference of the International Association of Historians of Asia, 24 - 28 June, 1991, held at the University of Hong Kong. G.P. V. Somaratna, "Jayawardanapura: The Capital of the Kingdom of Sri Lanka 1400-1565", The Sri Lanka Archives vol. II. pp. I - 7, and "Rise and Fall of the Fortress of Jayawardanapura", University of Colombo Review, vol. X, pp. 98-112. C. R. de Silva, "Frontier Fortress to Royal City: The City of Jayawardanapura Kotte", Modern Sri Lankan Studies vol.II, pp. -

Project for Formulation of Greater Kandy Urban Plan (Gkup)

Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development Urban Development Authority Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text September 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. NIKKEN SEKKEI Research Institute EI ALMEC Corporation JR 18-095 Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development Urban Development Authority Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text September 2018 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. NIKKEN SEKKEI Research Institute ALMEC Corporation Currency Exchange Rate September 2018 LKR 1 : 0.69 Yen USD 1 : 111.40 Yen USD 1 : 160.83 LKR Map of Greater Kandy Area Map of Centre Area of Kandy City THE PROJECT FOR FORMULATION OF GREATER KANDY URBAN PLAN (GKUP) Final Report Volume 2: Main Text Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PART 1: INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Objective and Outputs of the Project ....................................................... 1-2 1.3 Project Area ............................................................................................. 1-3 1.4 Implementation Organization Structure ................................................... -

CEYLON TEA, the Journey - Sri Lanka - Part II - Guest Post by Linda Villano, Serendipitea

CEYLON TEA, The Journey - Sri Lanka - Part II - Guest Post by Linda Villano, SerendipiTea Monday, April 3rd 2017 @ 12:44 PM Continuing on from Part I, below are more highlights of my time spent with The Tea House Times on a trip to Sri Lanka . Since our return, numerous Ceylon tea focused posts appear through various channels of The Tea House Times: here in my personal blog, in Gail Gastelu’s blog, as well as in a focused feature blog for Sri Lanka. In addition, Ceylon Tea themed articles are featured in 2017 issues of The Tea House Times and will continue to be featured through August, the month marking big anniversary celebrations throughout Sri Lanka. So many photos were taken during this journey I feel a great need to share. Please make a pot of your favorite Ceylon tea, grab a cuppa and hop in a Tuk Tuk. Enjoy the voyage. BELOW *Ceylon Chamber of Commerce Colombo Tea Auction *Ceylon Chamber of Commerce Tea Facts * Colombo Tea Auction Catalog at the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce *Cuppa Milk Tea at the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce *ROADSIDE MARKET BioFoods Organic Tea Factory - Raw Material BioFoods Organic Tea Factory - Roller BioFoods Organic Tea Factory - Comparing Tea Grades BioFoods Organic Tea Factory - Hand Packing BioFoods Organic Tea Factory Cleaning Equipment Rack BioFoods Organic Tea Factory Green Tea & Garden Grown Banana *Unilever Instant Tea Factory Board Room *Unilever Instant Tea Factory *Sri Lanka Rupees ~ a day of leisure! *Bentota Beach Resort by Cinnamon A day of leisure! *Bentota Beach Resort Tea Samovar *Bentota Beach Resort Tea Cocktail & Tea Mocktail Menu *Bye Bye Sri Lanka & Thanks for the Memories! LEARN MORE Sri Lanka Tea Board Website: http://www.pureceylontea.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Sri-Lanka-Tea- Board/181010221960446 ~ Linda Villano, SerendipiTea . -

6 Production Details of Organic Tea Estates in Sri Lanka

Status of organic agriculture in Sri Lanka with special emphasis on tea production systems (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades „Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften“ am Fachbereich Pflanzenbau der Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen PhD Thesis Faculty of Plant Production, Justus-Liebig-University of Giessen vorgelegt von / submitted by Ute Williges OCTOBER 2004 Acknowledgement The author gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance received from the German Academic Exchange Service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, DAAD) for the field work in Sri Lanka over a peroid of two years and the „Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsprogramm (HWP)“ for supporting the compilation of the thesis afterwards in Germany. My sincere thanks goes to my teacher Prof. Dr. J. Sauerborn whose continuous supervision and companionship accompanied me throughout this work and period of live. Further I want to thank Prof. Dr. Wegener and Prof. Dr. Leithold for their support regarding parts of the thesis and Dr. Hollenhorst for his advice carrying out the statistical analysis. My appreciation goes to Dr. Nanadasena and Dr. Mohotti for their generous provision of laboratory facilities in Sri Lanka. My special thanks goes to Mr. Ekanayeke whose thoughts have given me a good insight view in tea cultivation. I want to mention that parts of the study were carried out in co-operation with the Non Governmental Organisation Gami Seva Sevana, Galaha, Bio Foods (Pvt) Ltd., Bowalawatta, the Tea Research Institute (TRI) of Sri Lanka, Talawakele; The Tea Small Holders Development Authority (TSHDA), Regional Extension Centre, Sooriyagoda; The Post Graduate Institute of Agriculture (PGIA), Department of Soil Science, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya and The Natural Resources Management Services (NRMS), Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka, Polgolla. -

Mimi's Tranquili-Tea

Mimi’s Teas ~ A Loose Leaf Tea Shoppe Menu of Tea ~Black Tea~ Apple Spice Premium Ceylon Black Tea with Apple Bits, Cinnamon Pieces, and Cloves $3.15/oz Apricot Black Tea Premium Black Tea Blend & Flavors $3.15/oz Banana Sundae China Black Tea, Milk Chocolate Drops, Banana Chips, Flavor $3.15/oz Black Currant Premium Ceylon Black Tea, With Natural Black Currant Flavor $3.25/oz Black Velvet Organic China Black Tea, Ginseng, Peppermint, & Licorice $4.75/oz 1 Mimi’s Teas ~ A Loose Leaf Tea Shoppe Menu of Tea Buddha’s Delight Tea Premium Black Tea with Apple its, Orange Peel, Currants, Cinnamon, Almond Flakes, Cloves, and Safflowers $4.35/oz Cha Cha Chai Organic Indian Black Tea Blend Organic Ginger, Organic Cinnamon, Organic Cardamom, Organic Clove & Organic Pepper $4.15/oz Cherry India Black Tea, Safflowers, Cherries, & Cherry Flavor $2.95/oz Cherry Cordial Black Tea, Cherry, & Chocolate Bits ~natural & artificial flavor~ $3.15/oz Chocolate Almond Black Tea, Almond, Cocoa Beans ~artificial flavor~ $3.15/oz Chocolate Supreme Black Tea, Chocolate Bits, Natural & Artificial Flavor ~contains soy~ $3.55/oz 2 Mimi’s Teas ~ A Loose Leaf Tea Shoppe Menu of Tea Coconut Heaven Naturally Flavored Premium Black Tea, & Shredded Coconut $3.35/oz Earl Grey Manhattan Blend Vintage British Black Tea Blend with Bergamot & Flowers $3.95/oz Earl Grey Special Blend Premium Ceylon Black Tea with Bergamot & Vanilla $3.45/oz Decaf Earl Grey Naturally Decaffeinated Natural Bergamot Flavored Black Tea $4.95/oz Ginger Peach Premium Ceylon Black Tea Flavored with -

Post-Tsunami Redevelopment and the Cultural Sites of the Maritime Provinces in Sri Lanka

Pali Wijeratne Post-Tsunami Redevelopment and the Cultural Sites of the Maritime Provinces in Sri Lanka Introduction floods due to heavy monsoon rains, earth slips and land- slides and occasional gale force winds caused by depres- Many a scholar or traveller in the past described Sri Lanka sions and cyclonic effects in either the Bay of Bengal or as »the Pearl of the Indian Ocean« for its scenic beauty and the Arabian Sea. Sri Lanka is not located in the accepted nature’s gifts, the golden beaches, the cultural riches and seismic region and hence the affects of earthquakes or the mild weather. On that fateful day of 26 December 2004, tsunamis are unknown to the people. The word ›tsunami‹ within a matter of two hours, this resplendent island was was not in the vocabulary of the majority of Sri Lankans reduced to a »Tear Drop in the Indian Ocean.« The Indian until disaster struck on that fateful day. Ocean tsunami waves following the great earthquake off The great historical chronicle »Mahavamsa« describes the coast of Sumatra in the Republic of Indonesia swept the history of Sri Lanka from the 5th c. B. C. This chronicle through most of the maritime provinces of Sri Lanka, reports an incident in the 2nd c. B. C. when »the sea-gods causing unprecedented damage to life and property. made the sea overflow the land« in the early kingdom of There was no Sri Lankan who did not have a friend or Kelaniya, north of Colombo. It is to be noted that, by acci- relation affected by this catastrophe. -

Silence in Sri Lankan Cinema from 1990 to 2010

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright SILENCE IN SRI LANKAN CINEMA FROM 1990 TO 2010 S.L. Priyantha Fonseka FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Sydney 2014 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

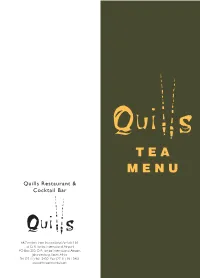

Quills Tea Menu

TEA MENU Quills Restaurant & Cocktail Bar 68.7 metres from International Arrivals Hall at O. R. Tambo International Airport PO Box 200, O. R. Tambo International Airport Johannesburg, South Africa Tel: (27 11) 961 5400 Fax: (27 11) 961 5401 www.intercontinental.com QUILLS TEA MENU SUPREME CEYLON ENGLISH BREAKFAST TEA Ceylon Tea was recognized as the finest since the late Sweet and Savoury 210pp 1800s when its bright, full bodied teas made tea and Ceylon famous throughout Europe. This Ceylon Broken Inclusive of a glass of Cap Classique 310pp Orange Pekoe is the quintessential Ceylon, offering body, brightness, structure, strength and colour; the Inclusive of a glass of Champagne 365pp features that made Ceylon the home of the finest teas. SWEET DELIGHTS THE ORIGINAL EARL GREY Chef’s Selection of Sweet Delicacies The legend of Earl Grey Tea is one of politics and intrigue. Freshly Baked Cheese and Plain Scones with When a British diplomat saved the life of an official of the Vanilla Pod Cream, Home Made Preserves and Praline Imperial Chinese Court, tea enhanced with the peel of a special A Selection of Afternoon Tea Pastries and Cakes variety of orange, and its recipe were given to Charles, 2nd Earl Fresh Seasonal Fruit with Sweet Dipping Sauce of Grey, also then the Prime Minister of England. The tea that became known as 'Earl Grey Tea' combines tea with the flavour SAVOURY of Bergamot. Tea Sandwiches Smoked Salmon, Cream Cheese and Cucumber VANILLA CEYLON Spicy Chicken Mayonnaise A light, bright tea with a sensual and aromatic finish. The Caprese combination of high grown Ceylon and the inspiring aroma of Selection of Savoury Quiches and Mini Pies vanilla make this a delightful tea. -

CONTENTS Chapter Preface Introduction 1

CONTENTS Chapter Preface Introduction 1. Sri Lanka 2. Prehistoric Lanka; Ravana abducts Princess Sita from India.(15) 3 The Mahawamsa; The discovery of the Mahawamsa; Turnour's contribution................................ ( 17) 4 Indo-Aryan Migrations; The coming of Vijaya...........(22) 5. The First Two Sinhala Kings: Consecration of Vijaya; Panduvasudeva, Second king of Lanka; Princess Citta..........................(27) 6 Prince Pandukabhaya; His birth; His escape from soldiers sent to kill him; His training from Guru Pandula; Battle of Kalahanagara; Pandukabhaya at war with his uncles; Battle of Labu Gamaka; Anuradhapura - Ancient capital of Lanka.........................(30) 7 King Pandukabhaya; Introduction of Municipal administration and Public Works; Pandukabhaya’s contribution to irrigation; Basawakulama Tank; King Mutasiva................................(36) 8 King Devanampiyatissa; gifts to Emporer Asoka: Asoka’s great gift of the Buddhist Doctrine...................................................(39) 9 Buddhism established in Lanka; First Buddhist Ordination in Lanka around 247 BC; Mahinda visits the Palace; The first Religious presentation to the clergy and the Ordination of the first Sinhala Bhikkhus; The Thuparama Dagoba............................ ......(42) 10 Theri Sanghamitta arrives with Bo sapling; Sri Maha Bodhi; Issurumuniya; Tissa Weva in Anuradhapura.....................(46) 11 A Kingdom in Ruhuna: Mahanaga leaves the City; Tissaweva in Ruhuna. ...............................................................................(52) -

Intimate Partner Violence in Sri Lanka: a Scoping Review

Paper Intimate partner violence in Sri Lanka: a scoping review S Guruge1, V Jayasuriya-Illesinghe1, N Gunawardena2, J Perera3 (Index words: intimate partner violence, scoping review, violence against women, Sri Lanka) Abstract (37.7%) [2]. A review of data from 81 countries revealed South Asia is considered to have a high prevalence of that South Asia has the second highest prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) against women. Therefore IPV (41.7%) [3]. Context specific information about IPV the World Health Organisation has called for context- in South Asia is needed to understand these alarming specific information about IPV from different regions. A prevalence rates, as well as to identify the determinants of scoping review of published and gray literature over the IPV and how these factors generate the conditions under last 35 years was conducted using Arksey and O’Malley’s which women experience IPV in these settings. framework. Reported prevalence of IPV in Sri Lanka ranged from 20-72%, with recent reports of rates ranging from 25- Despite sharing many characteristics with other 35%. Most research about IPV has been conducted in a South Asian countries, Sri Lanka consistently ranks few provinces and is based on the experience of legally better in terms of maternal and child health, and life married women. Individual, family, and societal risk factors expectancy and educational attainment of women, yet for IPV have been studied, but their complex relationships available research suggests that the country has high have not been comprehensively investigated. Health rates of IPV [4-6]. Sri Lanka is currently transitioning consequences of IPV have been reported, with particular from a low-to middle-income country and is emerging attention to physical health, but women are likely to under- from a 25-year-long civil war, so it is a unique context report sexual violence. -

Afternoon Tea Fine Teas Vintage Afternoon Tea

AFTERNOON TEA FINE TEAS VINTAGE AFTERNOON TEA SENCHA FUKUJYU TRADITIONAL AFTERNOON TEA The large flat leaves of this Japanese green tea give a silky, sweet and grassy taste. Adult £34 Child (Ages 5 – 11. No charge for children under 5) £18 DRAGON PEARL JASMINE CHAMPAGNE AFTERNOON TEA Beautiful hand-rolled pearls of green tea infused with jasmine flowers. Please be advised that a £2 supplement applies to this tea. Served with a glass of Laurent-Perrier La Cuvée, France, NV £46 Served with a glass of Laurent-Perrier Rosé Cuvée, France, NV £53 SILVER NEEDLES YIN ZHEN A rare Chinese white tea picked only two days a year – sweet and delicate, with hints of melon. SANDWICHES Please be advised that a £3 supplement applies to this tea. Smoked chicken with sweetcorn on onion bread Cucumber with cream cheese on caraway bread Poached and smoked salmon with lemon on basil bread Egg mayonnaise with watercress on wholemeal bread FRESHLY BAKED SCONES Strawberry preserve, seasonal compote and clotted cream PASTRIES Gateau St. Honoré Yorkshire rhubarb and yoghurt tart Coworth Park Black Forest gateaux Orange marmalade cake with cardamom cream Our menu contains allergens. If you suffer from an allergy or intolerance, please let a member of the Drawing Room team know upon placing your order. A discretionary service charge of 12.5% will be added to the bill. BRITISH HERITAGE TEAS WINTER WARMERS THE COWORTH PARK AFTERNOON BLEND CINNAMON WINTER SPICE A unique blend of muscatel Darjeeling, peach Formosa Oolong, a hint of Lapsang A rich blend of black teas, three types of cinnamon, orange peel, and sweet cloves. -

Interpretation of Source Material for the Study of Rela Tions Between Sri Lanka and Thailand Prior to Fourteenth Century*

INTERPRETATION OF SOURCE MATERIAL FOR THE STUDY OF RELA TIONS BETWEEN SRI LANKA AND THAILAND PRIOR TO FOURTEENTH CENTURY* By M. Rohanadeera Department of History and Archaeology University of Sri Jayawardenepura, Sri Lanka. INTRODUCTION THE recorded history of Thailand begins with the founding of the first independent Thai Kingdom in Sukhothai, ill the late 13th century. Its history from 14th century .onwards, has been satisfactorily documented with the help of abundant source mater-ial, both. literary and archaeolo- gical. Hence we have at our disposal, a not so complicated picture of what happened in the political and cultural spheres of that land during the period from 14th century onwards, with fairly established chronology. As such history of contacts between Sri Lanka and Thailand. during that period could be arranged in chronological sequence and historians have done S0 to a satisfactory degree. But the study of the subject relating to the period prior to 14th century is quite different, for not only are the source material rare, sporadic and clouded with myths and legends, but also as mentioned earlier, the history of Thailand itself is yet to be documented satisfactorily. On the other hand Sri Lankan history of the corresponding period is relatively clearand comprehensively documented with established chrono- logy. This has been done with the help of the bulk of information furnished in literary and archaeological sources. So, our primary task is to discover relevant evidence.jf any; in whatever form, in the dark period-of Thai history and to identify their parallels in the clear picture of Sri Lankan history prior to 14th century.