The Sinhalese Diaspora in the United Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration and Morality Amongst Sri Lankan Catholics

UNLIKELY COSMPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Bernardo Enrique Brown August, 2013 © 2013 Bernardo Enrique Brown ii UNLIKELY COSMOPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS Bernardo Enrique Brown, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2013 Sri Lankan Catholic families that successfully migrated to Italy encountered multiple challenges upon their return. Although most of these families set off pursuing very specific material objectives through transnational migration, the difficulties generated by return migration forced them to devise new and creative arguments to justify their continued stay away from home. This ethnography traces the migratory trajectories of Catholic families from the area of Negombo and suggests that – due to particular religious, historic and geographic circumstances– the community was able to develop a cosmopolitan attitude towards the foreign that allowed many of its members to imagine themselves as ―better fit‖ for migration than other Sri Lankans. But this cosmopolitanism was not boundless, it was circumscribed by specific ethical values that were constitutive of the identity of this community. For all the cosmopolitan curiosity that inspired people to leave, there was a clear limit to what values and practices could be negotiated without incurring serious moral transgressions. My dissertation traces the way in which these iii transnational families took decisions, constantly navigating between the extremes of a flexible, rootless cosmopolitanism and a rigid definition of identity demarcated by local attachments. Through fieldwork conducted between January and December of 2010 in the predominantly Catholic region of Negombo, I examine the work that transnational migrants did to become moral beings in a time of globalization, individualism and intense consumerism. -

The Entrenchment of Sinhalese Nationalism in Post-War Sri Lanka by Anne Gaul

An Opportunity Lost The Entrenchment of Sinhalese Nationalism in Post-war Sri Lanka by Anne Gaul Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervised by: Dr. Andrew Shorten Submitted to the University of Limerick, November 2016 Abstract This research studies the trajectory of Sinhalese nationalism during the presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa from 2005 to 2015. The role of nationalism in the protracted conflict between Sinhalese and Tamils is well understood, but the defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in 2009 has changed the framework within which both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalism operated. With speculations about the future of nationalism abound, this research set out to address the question of how the end of the war has affected Sinhalese nationalism, which remains closely linked to politics in the country. It employs a discourse analytical framework to compare the construction of Sinhalese nationalism in official documents produced by Rajapaksa and his government before and after 2009. A special focus of this research is how through their particular constructions and representations of Sinhalese nationalism these discourses help to reproduce power relations before and after the end of the war. It argues that, despite Rajapaksa’s vociferous proclamations of a ‘new patriotism’ promising a united nation without minorities, he and his government have used the momentum of the defeat of the Tamil Tigers to entrench their position by continuing to mobilise an exclusive nationalism and promoting the revival of a Sinhalese-dominated nation. The analysis of history textbooks, presidential rhetoric and documentary films provides a contemporary empirical account of the discursive construction of the core dimensions of Sinhalese nationalist ideology. -

Beyond Remittances: the Role of Diaspora in Poverty Reduction in Their Countries of Origin

Beyond Remittances: The Role of Diaspora in Poverty Reduction in their Countries of Origin A Scoping Study by the Migration Policy Institute for the Department of International Development July 2004 By Kathleen Newland, Director with Erin Patrick, Associate Policy Analyst Migration Policy Institute 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20036 202-266-1940 www.migrationpolicy.org The Migration Policy Institute is an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit think tank dedicated to the study of the movement of people worldwide. The Institute provides knowledge-based analysis, development, and evaluation of migration and refugee policies at the local, national, and international levels. Additional information on migration and development can be found on the Migration Information Source, MPI’s web-based resource for current and accurate migration and refugee data and analysis at www.migrationinformation.org. i Table of Contents Executive Summary iv Introduction 1 Table 1: Resource flows to developing countries (in billions of US$) Part I: Overview of Country of Origin Policies and Practice towards Diaspora 3 China Table 2: Foreign Direct Investment Inflows in China, (1990-2001) India Table 3: Percentage Distribution of NRIs and PIOs by Region Text Box: “Investment or remittances? Chinese and Indian Patterns” Eritrea Table 4: Total Number of Eritrean Refugees, 1992-2003 The Philippines Mexico Table 5: Stock of Foreign Born from Mexico in the United States, 1995-2003 Taiwan Reflections Part II: Diaspora Engagement in Countries of Origin 14 Home Town Associations Business Networks Building Social Capital Perpetuating Conflict Moderating Conflict Philanthropy Reflections Part III: Donors’ Engagement with Diaspora 23 Human Capital Programs Community Development Research Building Capacity in Diaspora Communities Reflections ii Part IV: Recommendations 28 1. -

Engaging the Tamil Diaspora in Peace-Building Efforts in Sri Lanka Michael Potters

Undergraduate Transitional Justice Review Volume 1 | Issue 3 Article 5 2010 Engaging the Tamil Diaspora in Peace-Building Efforts in Sri Lanka Michael Potters Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/undergradtjr Recommended Citation Potters, Michael (2010) "Engaging the Tamil Diaspora in Peace-Building Efforts in Sri Lanka," Undergraduate Transitional Justice Review: Vol. 1 : Iss. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/undergradtjr/vol1/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Transitional Justice Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Potters: Engaging the Tamil Diaspora in Peace-Building Efforts in Sri Lank ENGAGING THE TAMIL DIASPORA IN PEACE-BUILDING EFFORTS IN SRI LANKA Michael Potters Refugees who have fled the conflict in Sri Lanka have formed large diaspora communities across the globe, forming one of the largest in Toronto, Canada. Members of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) have infiltrated these communities and elicited funding from its members, through both coercion and consent, to continue the fight in their home country. This paper will outline the importance of including these diaspora communities in peace-building efforts, and will propose a three-tier solution to enable these contributions. On the morning of October 17, 2009, Canadian authorities seized the vessel Ocean Lady off the coast of British Columbia, Canada. The ship had entered Canadian waters with 76 Tamil refugees on board, fleeing persecution and violence in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s long and violent civil war. -

An Aspect of the History of the Veddas of Sri Lanka"

Creolization, Legend and History: an Aspect of the History of the Veddas of Sri Lanka" The Veddas of Sri Lanka are a near extinct aboriginal community confined at the moment to a narrow strip of forest in the area east of the central hill country.! The census of 1881 recorded their number as 2,200. By 1958 it had dropped to 800 and by 1963 it had dwindled to such an extent that the Yeddas were no longer assigned a separate entry in the census and were included in the column for "other races".» Historians and anthropologists are generally agreed on the point that Yeddas are the descendants of the Stone Age Man of Sri Lanka whose traces have been found in places such as Bandarawela and Balangoda.P The Seligrnanns who did intensive field-work among the Veddas at the beginning of the present century have shown that there is considerable evidence to suggest that once the Yedda country embraced "the whole of Uva and much of the Central and North Central provinces, while there is no reason to suppose that their territory did not extend beyond these limits.":' However, with the advent of the Aryan settlers in the sixth century B.C. who established a hydraulic civilization in the north central and south eastern plains, the Veddas seem to have retreated towards the upper basin of the Mahaweli. With the final collapse of the hydraulic civilization and the drift of the Sinhalese population to the south west which began towards the thirteenth century> the Veddas again seem to have extended their activities north and eastwards. -

Un Global Compact Communication on Progress (Cop)

Mabroc Teas (Pvt.) Ltd - 2019/2020 UN GLOBAL COMPACT COMMUNICATION ON PROGRESS (COP) 1.0 Statement of Continued Support 6th February 2020 To our stakeholders, With all the difficulties experienced in the international market place during the year 2019, Mabroc Teas continued communicating the commitment to the principles of the United Nations Global Compact reaffirming the ten principles in the areas of Human Rights, Labor, Environment and Anti-Corruption. The ethical business practices we follow on the guidelines of UNGC was further strengthened by Mabroc by integrating the Global Compact and its principles into our business strategy, culture and daily operations. We are also committed to share this information with our stakeholders using our primary channels of communication. We would like to take this opportunity to wish the United Nations Global Compact continued success in their endeavors in promoting these noble principles around the world. Yours Sincerely, MABROC TEAS (PVT.) LTD. Niran Ranatunge Managing Director 1 Mabroc Teas (Pvt.) Ltd - 2019/2020 2.0 Mabroc Teas Corporate Sustainability Programme: Tea without Tears Tea without tears (TWT) is our way of taking care of our most valuable asset, our human resources irrespective of designation of seniority; it is them who make up the Mabroc family. Each and every person engaged in the company contributes his/her might in creating the fine quality tea that Mabroc is reputed the world over. Tea without tears was started in 2008 by our own employees. During the period of 2019 we accomplished quite a few projects and we have listed some of them in this report. -

Handbook of Religious Beliefs and Practices

STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES 1987 FIRST REVISION 1995 SECOND REVISION 2004 THIRD REVISION 2011 FOURTH REVISION 2012 FIFTH REVISION 2013 HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES INTRODUCTION The Department of Corrections acknowledges the inherent and constitutionally protected rights of incarcerated offenders to believe, express and exercise the religion of their choice. It is our intention that religious programs will promote positive values and moral practices to foster healthy relationships, especially within the families of those under our jurisdiction and within the communities to which they are returning. As a Department, we commit to providing religious as well as cultural opportunities for offenders within available resources, while maintaining facility security, safety, health and orderly operations. The Department will not endorse any religious faith or cultural group, but we will ensure that religious programming is consistent with the provisions of federal and state statutes, and will work hard with the Religious, Cultural and Faith Communities to ensure that the needs of the incarcerated community are fairly met. This desk manual has been prepared for use by chaplains, administrators and other staff of the Washington State Department of Corrections. It is not meant to be an exhaustive study of all religions. It does provide a brief background of most religions having participants housed in Washington prisons. This manual is intended to provide general guidelines, and define practice and procedure for Washington State Department of Corrections institutions. It is intended to be used in conjunction with Department policy. While it does not confer theological expertise, it will, provide correctional workers with the information necessary to respond too many of the religious concerns commonly encountered. -

YAMU.LK PP- YAMU Range Ad Oct 15 FINAL.Pdf 1 10/15/15 2:55 PM

FREE The Sushi Bento at Naniyori MARCH/2016 WWW.YAMU.LK PP- YAMU Range Ad Oct 15 FINAL.pdf 1 10/15/15 2:55 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K PP- YAMU Range Ad Oct 15 FINAL.pdf 1 10/15/15 2:55 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 4 [insert title here] - this is the actual title We’ve got some great stuff in this issue. We did our first EDITORIAL ever quiz, where you can gauge your competency as a Indi Samarajiva Colombar. If you feel inadequate after that, we’ve hooked Bhagya Goonewardhane you up with a guide to 24 hours in Colombo to impress Aisha Nazim Imaad Majeed your visiting friends! Shifani Reffai Kinita Shenoy We’ve also done lots of chill travels around the island, from Batti to Koggala Lake to Little Adam’s Peak. There’s ADVERTISING going to be plenty more coming up as we go exploring Dinesh Hirdaramani during the April holidays, so check the site yamu.lk for 779 776 445 / [email protected] more. CONTACT 11 454 4230 (9 AM - 5 PM) With the Ides of March around the corner, just remember [email protected] that any salad is a Caesar Salad if you stab it enough. PRINTED BY Imashi Printers ©2015 YAMU (Pvt) Ltd 14/15A Duplication Road, Col 4 kinita KIITO WE DO SUITS Damith E. Cooray CText ATI Head Cutter BSc (Hons) International Clothing Technology & Design Manchester Metropolitan University, UK Sole Distributor of Flagship Store KIITO Bespoke & Workshop # 19 , First Floor, Auditor General’s Department Building # 27, Rosmead Place Arcade Independance Square Colombo 07 Colombo 07 0112 690740 0112 675670 8 SCARLET ROOM 32, Alfred House Avenue, Colombo 03 | 11 4645333 BY BHAGYA their dishes with the exception Risotto Paella (Rs. -

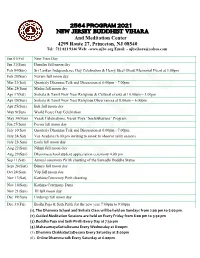

2564 PROGRAM 2021 New Jersey Buddhist Vihara and Meditation Center

2564 PROGRAM 2021 New Jersey Buddhist Vihara And Meditation Center 4299 Route 27, Princeton, NJ 08540 Tel: 732 821 9346 Web: -www.njbv.org Email: - [email protected] Jan 01(Fri) New Year Day Jan 31(Sun) Duruthu full moon day Feb 04(Sun) Sri Lankan Independence Day Celebration & Henry Steel Olcott Memorial Event at 3:00pm Feb 28(Sun) Navam full moon day Mar 21(Sat) Quarterly Dhamma Talk and Discussion at 6:00pm - 7.00pm Mar 28(Sun) Madin full moon day Apr 17(Sat) Sinhala & Tamil New Year Religious & Cultural events at 10.00am – 3.00pm Apr 18(Sun) Sinhala & Tamil New Year Religious Observances at 8.00am – 6.00pm Apr 25(Sun) Bak full moon day May 9(Sun) World Peace Day Celebration May 30(Sun) Vesak Celebrations, Vesak Poya “SeelaBhavana” Program Jun 27(Sun) Poson full moon day July 10(Sat) Quarterly Dhamma Talk and Discussion at 6:00pm - 7.00pm July 24(Sat) Vas Aradana (6.00 pm inviting to monk to observe rainy season) July 25(Sun) Esala full moon day Aug 22(Sun) Nikini full moon day Aug 29(Sun) Dhamma school student appreciation ceremony 4.00 pm Sep 11(Sat) Annual ceremony Pirith chanting of the Samadhi Buddha Statue Sept 26(Sun) Binara full moon day Oct 24(Sun) Vap full moon day Nov 13(Sat) Kathina Ceremony Prith chanting Nov 14(Sun) Kathina Ceremony Dana Nov 21(Sun) Ill full moon day Dec 19(Sun) Unduvap full moon day Dec 31(Fri) Bodhi Puja & Seth Pirith for the new year 7:00pm to 9:00pm (1). -

Migration, Development and Natural Disasters: Insights from the Indian Ocean Tsunami

Migration, Development and Natural Disasters: Also available online at: M R Insights from the http://www.iom.int S 30 Indian Ocean Tsunami When natural disasters strike populated areas, the toll in human lives, infrastructure and economic activities can be devastating and long-lasting. No. 30 The psychological effects can be just as debilitating, instilling fear and discouragement in the affected populations. But, adversity also brings forth the strongest and best in human beings, and reveals initiatives, capacities and courage not perceived before. How is development undermined by natural disasters, what is the effect on migrants and migratory fl ows and what is the role of migration in mitigating some of the worst effects of natural calamities? This paper explores how the advent of a natural disaster interplays with the migration-development nexus by reviewing the impact of the Indian Ocean Tsunami on migration issues in three affected countries; Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. This paper focuses on three particular aspects of how natural disasters interplay with the migration/development dynamic: (a) Impact of natural disasters on migrant communities, in particular heightened vulnerabilities and lack of access to humanitarian/development assistance; (b) Effect of natural disasters on migratory fl ows into and out of affected areas due to socio-economic changes which undermine pre-disaster development levels, (c) Diaspora response and support in the aftermath of disaster and the degree to which this can offset losses and bolster “re-development”. ISSN 1607-338X IOM • OIM US$ 16.00 mrs30cover.indd 1 5/7/2007 5:32:52 PM The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily IOM Migration Research Series (MRS) refl ect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). -

Institutionalising Diaspora Linkage the Emigrant Bangladeshis in Uk and Usa

Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employmwent INSTITUTIONALISING DIASPORA LINKAGE THE EMIGRANT BANGLADESHIS IN UK AND USA February 2004 Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment, GoB and International Organization for Migration (IOM), Dhaka, MRF Opinions expressed in the publications are those of the researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an inter-governmental body, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and work towards effective respect of the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher International Organization for Migration (IOM), Regional Office for South Asia House # 3A, Road # 50, Gulshan : 2, Dhaka : 1212, Bangladesh Telephone : +88-02-8814604, Fax : +88-02-8817701 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : http://www.iow.int ISBN : 984-32-1236-3 © [2002] International Organization for Migration (IOM) Printed by Bengal Com-print 23/F-1, Free School Street, Panthapath, Dhaka-1205 Telephone : 8611142, 8611766 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher. -

Silence in Sri Lankan Cinema from 1990 to 2010

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright SILENCE IN SRI LANKAN CINEMA FROM 1990 TO 2010 S.L. Priyantha Fonseka FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Sydney 2014 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text.