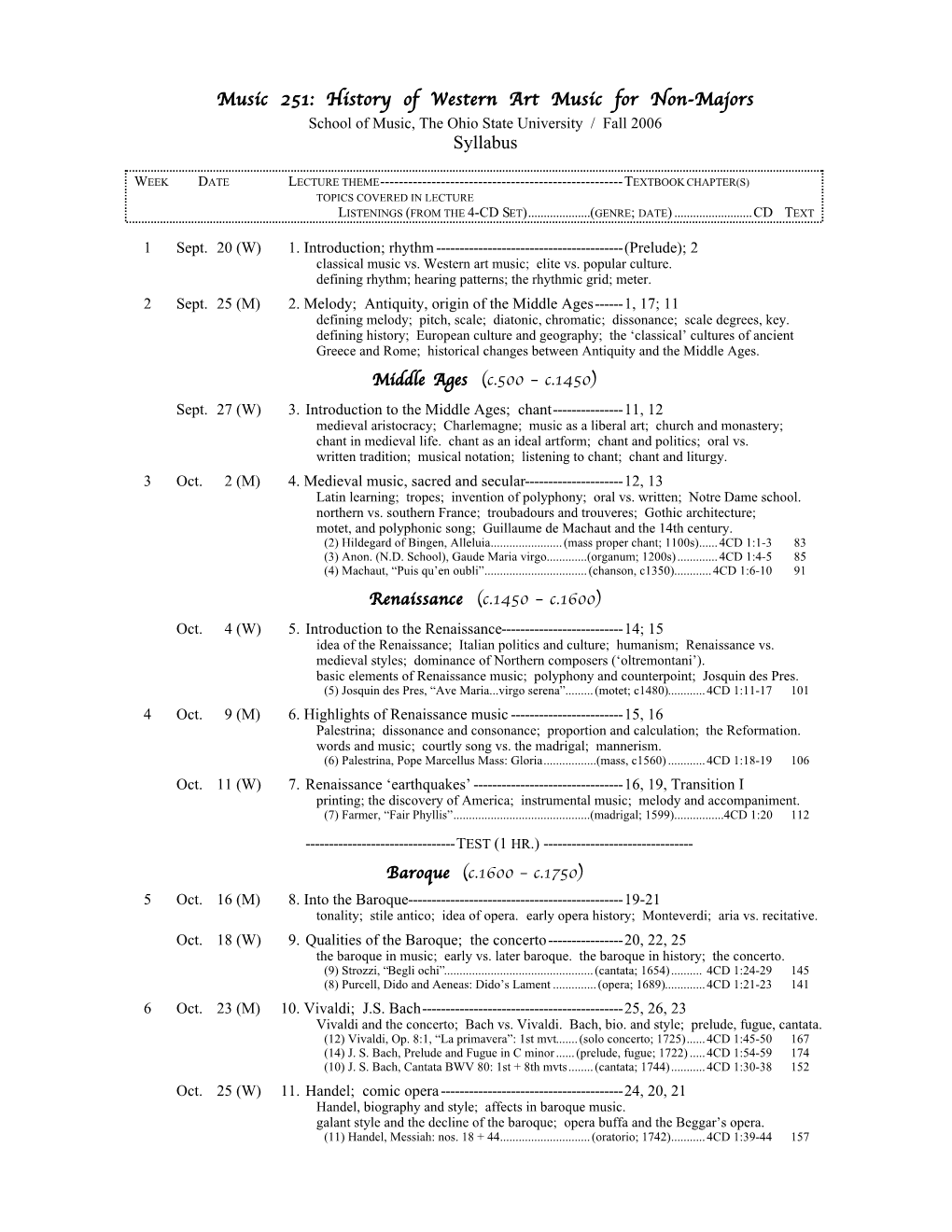

History of Western Art Music for Non-Majors Syllabus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title of Creative Art Disseminating Thai Classical Music Arrangement for Symphonic Band : Siam Symphonic Band • Name –Surn

th The 5 International Creative Disseminating 2018 Title of Creative Art Disseminating Thai Classical Music Arrangement for Symphonic Band : Siam Symphonic Band Name –Surname Yos Vaneesorn Academic Status Full-time lecturer Faculty of Music University: Silpakorn University Country: Thailand E-mail address [email protected] Tel. 086-4125248 Thesis Advisors - Abstract Siam Symphonic Band is one of the creative research projects in music funded by Thailand Research Fund and led by Natchar Pancharoen who conducted the project concentrating on Thai classical music repertoire of Rattanakosin in 2017. The Siam Symphonic Band project aims to create arrangements of Thai classical music for symphonic bands in order to promote an exquisitely elegant Thai tunes and to show how composers can transcribe Thai classical music into a standard symphonic band repertoire. The process of this project provides 3 types of musical arranging methods as of the following: 1) a traditional type, which preserves several important elements of Thai classical music such as formal structures and textures, 2) a popular type, which has been favorable among Thai arrangers and mostly consisting of homophonic texture added with some modern harmonic languages, and 3) a new original type, which applies compositional techniques of modern music and a concept of transferring the original sound of Thai music into a sonority of the symphonic band. 22 th The 5 International Creative Disseminating 2018 The album called ‘Siam Symphonic Band’ consists of 10 new music arranging pieces for symphonic bands and was published as cds with music scores and elucidation. The pieces were recorded by Feroci Philharmonic Winds and conducted by Vanich Potavanich. -

Multiple Choice

Unit 4: Renaissance Practice Test 1. The Renaissance may be described as an age of A. the “rebirth” of human creativity B. curiosity and individualism C. exploration and adventure D. all of the above 2. The dominant intellectual movement of the Renaissance was called A. paganism B. feudalism C. classicism D. humanism 3. The intellectual movement called humanism A. treated the Madonna as a childlike unearthly creature B. focused on human life and its accomplishments C. condemned any remnant of pagan antiquity D. focused on the afterlife in heaven and hell 4. The Renaissance in music occurred between A. 1000 and 1150 B. 1150 and 1450 C. 1450 and 1600 D. 1600 and 1750 5. Which of the following statements is not true of the Renaissance? A. Musical activity gradually shifted from the church to the court. B. The Catholic church was even more powerful in the Renaissance than during the Middle Ages. C. Every educated person was expected to be trained in music. D. Education was considered a status symbol by aristocrats and the upper middle class. 6. Many prominent Renaissance composers, who held important posts all over Europe, came from an area known at that time as A. England B. Spain C. Flanders D. Scandinavia 7. Which of the following statements is not true of Renaissance music? A. The Renaissance period is sometimes called “the golden age” of a cappella choral music because the music did not need instrumental accompaniment. B. The texture of Renaissance music is chiefly polyphonic. C. Instrumental music became more important than vocal music during the Renaissance. -

A Listening Guide for the Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini

A Listening Guide for The Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini 1 The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide Anthony Tommasini A listening guide INTRODUCTION: The Greatness Complex Bach, Mass in B Minor I: Kyrie I begin the book with my recollection of being about thirteen and putting on a recording of Bach’s Mass in B Minor for the first time. I remember being immediately struck by the austere intensity of the opening choral singing of the word “Kyrie.” But I also remember feeling surprised by a melodic/harmonic shift in the opening moments that didn’t do what I thought it would. I guess I was already a musician wanting to know more, to know why the music was the way it was. Here’s the grave, stirring performance of the Kyrie from the 1952 recording I listened to, with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. Though, as I grew to realize, it’s a very old-school approach to Bach. Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Vienna Philharmonic (12:17) Today I much prefer more vibrant and transparent accounts, like this great performance from Philippe Herreweghe’s 1996 recording with the chorus and orchestra of the Collegium Vocale, which is almost three minutes shorter. Philippe Herreweghe, conductor; Collegium Vocale Gent (9:29) Grieg, “Shepherd Boy” Arthur Rubinstein, piano Album: “Rubinstein Plays Grieg” (3:26) As a child I loved “Rubinstein Plays Grieg,” an album featuring the great pianist Arthur Rubinstein playing piano works by Grieg, including several selections from the composer’s volumes of short, imaginative “Lyrical Pieces.” My favorite was “The Shepherd Boy,” a wistful piece with an intense middle section. -

Real-Time Composition As a Strategy for the 21St Century Composer

Escola Superior de Música e das Artes do Espectáculo Real-Time Composition as a Strategy for the 21st Century Composer Óscar Rodrigues A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Composition and Music Theory supervised by Prof. Dimitris Andrikopoulos September 27, 2016 Abstract Real-Time Composition, despite being a term commonly used in computer music and free improvisation circles, is also one whose definition is not clear. This dissertation aims to, in seeking and attempting its conceptualisation, permit a deeper look at the core of the activity of western classical music making. By discussing the concepts and current views on composition, improvisation, musical work, interpretation and performance, we will propose a working definition that will later serve as a model for music making; one that involves both the composer and performers, influenced by their context, as creators. This model borrows heavily from Walter Thompson’s Soundpainting technique. We will then analyse the outcome of three different concerts, of increasing complexity and level of control, that resulted from the previous discussion and end by concluding that Real-Time Composition is, in fact, fundamentally different from improvisation, and an extension of western classical music practice. Keywords: real-time composition, improvisation, soundpainting Abstract A Composição em Tempo Real, apesar de ser um termo regularmente utilizado nos cír- culos da música electrónica e da improvisação livre, não tem uma definição clara. Esta dissertação tem como objectivo, ao procurar a sua conceptualização, perceber de forma mais profunda o núcleo da actividade produtiva da música clássica ocidental. Ao discutir os con- ceitos e entendimentos correntes de composição, improvisação, obra musical, interpretação e performance, será proposta uma definição operacional que irá posteriormente servir como modelo para a criação musical; este modelo envolve tanto compositores como intérpretes, influenciados pelo seu contexto, enquanto criadores. -

Baroque & Classical Music

Baroque & Classical Music Structure • Balanced phrasing (phrases are equal lengths, usually two or 4 bars long). • Question and answer (when a 2 or 4 bar phrase is answered by a phrase of an equal length). • Binary form (AB). Each section is repeated (look out for repeat signs). A change in key (home note) provides a contrast between the two sections. • Ternary form (ABA) • Rondo form (ABACA). • Theme and variation. A theme is played and then repeated with variations. Variations can be created in many ways e.g. by adding ornaments, changing the accompaniment, changing the instrumentation, inverting the melody. This is called melodic development. Other features • Ornamentation (twiddly bits / melodic decoration). For example: trill, turn and grace note. • In a trill, 2 next door notes alternate really quickly e.g. CDCDCDCDCDCDCD • A turn is made up of 4 next door notes shaped like this: or • Grace note/s are crushed very quickly onto the main melody note. They appear on the score as tiny notes e.g. • Sequences are created when a motive (a short bit of melody) is repeated on a different note. If the motive is repeated on a higher set of notes this is called an ascending sequence. If the motive is repeated on a lower set of notes this is called a descending sequence. • Imitation (especially in Baroque music) is created when a motive is copied, often by a different instrument or voice. • Melodic inversion is often used to create variation (e.g. CDE becomes EDC) • Ostinato (a repeating pattern, often occurs in an accompanying part) Tonality OR scales and harmonies • Major and minor keys, established in the Baroque period, continued to be used in the Classical period. -

How to Effectively Listen and Enjoy a Classical Music Concert

HOW TO EFFECTIVELY LISTEN AND ENJOY A CLASSICAL MUSIC CONCERT 1. INTRODUCTION Hearing live music is one of the most pleasurable experiences available to human beings. The music sounds great, it feels great, and you get to watch the musicians as they create it. No matter what kind of music you love, try listening to it live. This guide focuses on classical music, a tradition that originated before recordings, radio, and the Internet, back when all music was live music. In those days live human beings performed for other live human beings, with everybody together in the same room. When heard in this way, classical music can have a special excitement. Hearing classical music in a concert can leave you feeling refreshed and energized. It can be fun. It can be romantic. It can be spiritual. It can also scare you to death. Classical music concerts can seem like snobby affairs full of foreign terminology and peculiar behavior. It can be hard to understand what’s going on. It can be hard to know how to act. Not to worry. Concerts are no weirder than any other pastime, and the rules of behavior are much simpler and easier to understand than, say, the stock market, football, or system software upgrades. If you haven’t been to a live concert before, or if you’ve been baffled by concerts, this guide will explain the rigmarole so you can relax and enjoy the music. 2. THE LISTENER'S JOB DESCRIPTION Classical music concerts can seem intimidating. It seems like you have to know a lot. -

Medieval Music in Practice Studies in Honor of RICHARD CROCKER Medieval Music in Practice Studies in Honor of Medieval Music in Practice Richard Crocker

CrockerCover_v16a_MISCCover2013 5/2/13 3:13 PM Page 1 MISC $60.00 8 8 Miscellanea Medieval Music in Practice Studies in Honor of RICHARD CROCKER RICHARD of Honor in Studies Practice in Music Medieval Studies in Honor of Medieval Music in Practice Richard Crocker Richard Crocker once wrote “we understand many things about the history of music—specifically its development—better from the earlier periods.” Since his first publications in 1958, Crocker pio neered a radically phenomenological and critical approach to the study of early music and musical style. Medieval Music in Practice: Studies in Honor Studies in Honor of of Richard Crocker brings together eleven essays that take up Crocker’s call to consider the conti nuity of medieval and later musical practices in Photo (c) Kathleen Karn Richard Crocker performance, composition, and pedagogy. Two in troductory essays open this collection. Judith Peraino surveys the disciplinary questions that RICHARD LINCOLN CROCKER was born Feb Edited by emerge in Crocker’s work: What constitutes a co ruary 17, 1927 in Roxbury Massachusetts, and Judith A. Peraino herent category of music? What are the “ruling attended Yale University, receiving a B.A. (1950) ideas” of musicology? Richard Taruskin pays trib and a Ph.D. (1957) with a dissertation on “The ute to Crocker’s remarkable prescience in the Repertoire of Proses at St Martial de Limoges 1960s of antiessentialist and antiuniversalist ar (Tenth and Eleventh Centuries),” directed by Leo guments that characterized “new musicology” in Schrade. Crocker taught at Yale from 1955 until the 1980s. 1963, and at the University of California, Berkeley, Nine further essays focus on repertories from from 1963 until his retirement in 1994. -

Jazz Standards Arranged for Classical Guitar in the Style of Art Tatum

JAZZ STANDARDS ARRANGED FOR CLASSICAL GUITAR IN THE STYLE OF ART TATUM by Stephen S. Brew Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Luke Gillespie, Research Director ______________________________________ Ernesto Bitetti, Chair ______________________________________ Andrew Mead ______________________________________ Elzbieta Szmyt February 20, 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Stephen S. Brew iii To my wife, Rachel And my parents, Steve and Marge iv Acknowledgements This document would not have been possible without the guidance and mentorship of many creative, intelligent, and thoughtful musicians. Maestro Bitetti, your wisdom has given me the confidence and understanding to embrace this ambitious project. It would not have been possible without you. Dr. Strand, you are an incredible mentor who has made me a better teacher, performer, and person; thank you! Thank you to Luke Gillespie, Elzbieta Szmyt, and Andrew Mead for your support throughout my coursework at IU, and for serving on my research committee. Your insight has been invaluable. Thank you to Heather Perry and the staff at Stonehill College’s MacPhaidin Library for doggedly tracking down resources. Thank you James Piorkowski for your mentorship and encouragement, and Ken Meyer for challenging me to reach new heights. Your teaching and artistry inspire me daily. To my parents, Steve and Marge, I cannot express enough thanks for your love and support. And to my sisters, Lisa, Karen, Steph, and Amanda, thank you. -

What Classical Music Is (Not the Final Text, but a Riff on What

Rebirth: The Future of Classical Music Greg Sandow Chapter 4 – What Classical Music Is (not the final text, but a riff on what this chapter will say) In this chapter, I’ll try to define classical music. But why? Don’t we know what it is? Yes and no. We’re not going to confuse classical music with other kinds of music, with rock, let’s say, or jazz. But can we say how we make these distinctions? You’d think we could. And yet when we look at definitions of classical music—either formal ones, in dictionaries, or informal ones, that we’d deduce by looking around at the classical music world—we run into trouble. As we’ll see, these definitions imply that classical music is mostly old music (and, beyond that, old music only of a certain kind). And they’re full of unstated assumptions about classical music’s value. These assumptions, working in the background of our thoughts, make it hard to understand what classical music really is. We have to fight off ideas about how much better it might be than other kinds of music, ideas which—to people not involved with classical music, the very people we need to recruit for our future audience—can make classical music seem intimidating, pompous, unconvincing. And so here’s a paradox. When we expose these assumptions, when we develop a factual, value-free definition of classical music, only then can we find classical music’s real value, and convincingly set out reasons why it should survive. [2] Let’s start with common-sense definition of classical music, the one we all use, without much thought, when we say we know what classical music is when we hear it. -

Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship Musicology and Ethnomusicology 11-2018 Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation University of Denver, "Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography" (2018). Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship. 20. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/20 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Musicology and Ethnomusicology at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography This bibliography is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/20 Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography Andrews, Jean. "Teresa Berganza's Re-appropriation of Carmen." Journal of Romance Studies 14, no. 1 (2014): 19-39. Andrews speaks on how to fix a history of appropriation. Much of classical repertoire comes from past, made in a time when the population had different sensibilities. t is unfair to hold the past to modern sensibilities. Though modern performances of these works can be slightly changed to combat this history of appropriation. Andrews analysis Teresa Berganza contribution in changing the role to adhere to a better cultural context. Birnbaum, Michael. "Jewish Music, German Musicians: Cultural Appropriation and the Representation of a Minority in the German Klezmer Scene." Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 54, no. -

3. Medieval Music Worksheet.Pdf

3. Medieval Music Name:_______________________________________Date:__________ Each question is worth up to 4 points each (70%). The first essay is worth up to 30pts (30%). Your first and last name is 10pts (10%). 1. Much of the medieval attitude towards music was derived from classical antiquity, taken from who? 2. The Greek word for music “mousiké” comes directly from the word for the nine daughters of Zeus who inspired the creation of the arts. What were they called? 3. Early Christians rejected almost everything that was Roman and therefore pagan. However, the idea that music transmits and emphasizes a message to God was put forth by what early influential Christian leader and philosopher? 4. Early chant for centuries was credited to 6th century Pope Gregory I and was called Gregorian chant. We now know this is incorrect. What is a more sensible name for this type of music? 5. What is the singing style that sounds like an organ called? 6. What do we call one long note that sustains while other melodies are played over it? 7. Who do we credit for founding the origins of our modern system of written music? 8. By having the ability to write multiple lines of music, composers were able to write what important musical concept? 9. Who was the first composer to notate rhythm in church music and who also pioneered the answer to #8? 10. Name the type of traveling musicians who originated in Muslim Spain, but became extremely popular throughout Medieval Europe? 11. Notes that are a 4th or 5th apart from one another are considered “Perfect” and therefore Godly. -

Doctoral of Musical Arts Degree Band Conducting

DOCTORAL OF MUSICAL ARTS DEGREE BAND CONDUCTING Course Checklist □ 72 post baccalaureate semester hours completed □ Residency requirement satisfied (2 semesters of 9 s.h., or 3 semesters of 6 s.h. while holding at least a 25% assistantship) A. General Music Requirements (20 s.h.) □ 025:321 Introduction to Graduate Study in Music (2 s.h.) Music Theory: 9 s.h. (up to 6 s.h. can be counted from the master’s degree, upon written approval of the Associate Director for Graduate Studies) □ 025:240 Analytical Techniques (unless exempt through advisory exam) (3 s.h.) Students exempted from 025:240 through the advisory examination in music theory must substitute an additional theory elective from the following: □ 025:145 Counterpoint before 1600 (3 s.h.) □ 025:147 Counterpoint after 1600 (3 s.h) □ 025:247 Post-Tonal Analysis (3 s.h.) □ 025:249 Tonal Analysis (3 s.h.) □ 025:256 Special Topics in Theory and Analysis (3 s.h.) Electives chosen from the following courses: □ 025:145 Counterpoint before 1600 (3 s.h.) □ 025:147 Counterpoint after 1600 (3 s.h.) □ 025:241 History of Music Theory I (3 s.h.) □ 025:242 History of Music Theory II (3 s.h.) □ 025:247 Post-Tonal Analysis (3 s.h.) □ 025:249 Tonal Analysis (3 s.h.) □ 025:256 Special Topics in Theory and Analysis (3 s.h.) □ 025:311 Advanced Post-Tonal Theory and Analysis (3 s.h.) □ 025:312 Advanced Tonal Theory and Analysis (3 s.h.) Music History: 9 s.h. (up to 6 s.h. can be counted from the Master’s Degree, upon written approval of the Associate Director for Graduate Studies) □ 025:301 Advanced History