Fluency in General Music and Arts Technologies Is the Future of Music a Garage Band Mentality?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title of Creative Art Disseminating Thai Classical Music Arrangement for Symphonic Band : Siam Symphonic Band • Name –Surn

th The 5 International Creative Disseminating 2018 Title of Creative Art Disseminating Thai Classical Music Arrangement for Symphonic Band : Siam Symphonic Band Name –Surname Yos Vaneesorn Academic Status Full-time lecturer Faculty of Music University: Silpakorn University Country: Thailand E-mail address [email protected] Tel. 086-4125248 Thesis Advisors - Abstract Siam Symphonic Band is one of the creative research projects in music funded by Thailand Research Fund and led by Natchar Pancharoen who conducted the project concentrating on Thai classical music repertoire of Rattanakosin in 2017. The Siam Symphonic Band project aims to create arrangements of Thai classical music for symphonic bands in order to promote an exquisitely elegant Thai tunes and to show how composers can transcribe Thai classical music into a standard symphonic band repertoire. The process of this project provides 3 types of musical arranging methods as of the following: 1) a traditional type, which preserves several important elements of Thai classical music such as formal structures and textures, 2) a popular type, which has been favorable among Thai arrangers and mostly consisting of homophonic texture added with some modern harmonic languages, and 3) a new original type, which applies compositional techniques of modern music and a concept of transferring the original sound of Thai music into a sonority of the symphonic band. 22 th The 5 International Creative Disseminating 2018 The album called ‘Siam Symphonic Band’ consists of 10 new music arranging pieces for symphonic bands and was published as cds with music scores and elucidation. The pieces were recorded by Feroci Philharmonic Winds and conducted by Vanich Potavanich. -

A Listening Guide for the Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini

A Listening Guide for The Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini 1 The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide Anthony Tommasini A listening guide INTRODUCTION: The Greatness Complex Bach, Mass in B Minor I: Kyrie I begin the book with my recollection of being about thirteen and putting on a recording of Bach’s Mass in B Minor for the first time. I remember being immediately struck by the austere intensity of the opening choral singing of the word “Kyrie.” But I also remember feeling surprised by a melodic/harmonic shift in the opening moments that didn’t do what I thought it would. I guess I was already a musician wanting to know more, to know why the music was the way it was. Here’s the grave, stirring performance of the Kyrie from the 1952 recording I listened to, with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. Though, as I grew to realize, it’s a very old-school approach to Bach. Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Vienna Philharmonic (12:17) Today I much prefer more vibrant and transparent accounts, like this great performance from Philippe Herreweghe’s 1996 recording with the chorus and orchestra of the Collegium Vocale, which is almost three minutes shorter. Philippe Herreweghe, conductor; Collegium Vocale Gent (9:29) Grieg, “Shepherd Boy” Arthur Rubinstein, piano Album: “Rubinstein Plays Grieg” (3:26) As a child I loved “Rubinstein Plays Grieg,” an album featuring the great pianist Arthur Rubinstein playing piano works by Grieg, including several selections from the composer’s volumes of short, imaginative “Lyrical Pieces.” My favorite was “The Shepherd Boy,” a wistful piece with an intense middle section. -

Baroque & Classical Music

Baroque & Classical Music Structure • Balanced phrasing (phrases are equal lengths, usually two or 4 bars long). • Question and answer (when a 2 or 4 bar phrase is answered by a phrase of an equal length). • Binary form (AB). Each section is repeated (look out for repeat signs). A change in key (home note) provides a contrast between the two sections. • Ternary form (ABA) • Rondo form (ABACA). • Theme and variation. A theme is played and then repeated with variations. Variations can be created in many ways e.g. by adding ornaments, changing the accompaniment, changing the instrumentation, inverting the melody. This is called melodic development. Other features • Ornamentation (twiddly bits / melodic decoration). For example: trill, turn and grace note. • In a trill, 2 next door notes alternate really quickly e.g. CDCDCDCDCDCDCD • A turn is made up of 4 next door notes shaped like this: or • Grace note/s are crushed very quickly onto the main melody note. They appear on the score as tiny notes e.g. • Sequences are created when a motive (a short bit of melody) is repeated on a different note. If the motive is repeated on a higher set of notes this is called an ascending sequence. If the motive is repeated on a lower set of notes this is called a descending sequence. • Imitation (especially in Baroque music) is created when a motive is copied, often by a different instrument or voice. • Melodic inversion is often used to create variation (e.g. CDE becomes EDC) • Ostinato (a repeating pattern, often occurs in an accompanying part) Tonality OR scales and harmonies • Major and minor keys, established in the Baroque period, continued to be used in the Classical period. -

How to Effectively Listen and Enjoy a Classical Music Concert

HOW TO EFFECTIVELY LISTEN AND ENJOY A CLASSICAL MUSIC CONCERT 1. INTRODUCTION Hearing live music is one of the most pleasurable experiences available to human beings. The music sounds great, it feels great, and you get to watch the musicians as they create it. No matter what kind of music you love, try listening to it live. This guide focuses on classical music, a tradition that originated before recordings, radio, and the Internet, back when all music was live music. In those days live human beings performed for other live human beings, with everybody together in the same room. When heard in this way, classical music can have a special excitement. Hearing classical music in a concert can leave you feeling refreshed and energized. It can be fun. It can be romantic. It can be spiritual. It can also scare you to death. Classical music concerts can seem like snobby affairs full of foreign terminology and peculiar behavior. It can be hard to understand what’s going on. It can be hard to know how to act. Not to worry. Concerts are no weirder than any other pastime, and the rules of behavior are much simpler and easier to understand than, say, the stock market, football, or system software upgrades. If you haven’t been to a live concert before, or if you’ve been baffled by concerts, this guide will explain the rigmarole so you can relax and enjoy the music. 2. THE LISTENER'S JOB DESCRIPTION Classical music concerts can seem intimidating. It seems like you have to know a lot. -

Jazz Standards Arranged for Classical Guitar in the Style of Art Tatum

JAZZ STANDARDS ARRANGED FOR CLASSICAL GUITAR IN THE STYLE OF ART TATUM by Stephen S. Brew Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Luke Gillespie, Research Director ______________________________________ Ernesto Bitetti, Chair ______________________________________ Andrew Mead ______________________________________ Elzbieta Szmyt February 20, 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Stephen S. Brew iii To my wife, Rachel And my parents, Steve and Marge iv Acknowledgements This document would not have been possible without the guidance and mentorship of many creative, intelligent, and thoughtful musicians. Maestro Bitetti, your wisdom has given me the confidence and understanding to embrace this ambitious project. It would not have been possible without you. Dr. Strand, you are an incredible mentor who has made me a better teacher, performer, and person; thank you! Thank you to Luke Gillespie, Elzbieta Szmyt, and Andrew Mead for your support throughout my coursework at IU, and for serving on my research committee. Your insight has been invaluable. Thank you to Heather Perry and the staff at Stonehill College’s MacPhaidin Library for doggedly tracking down resources. Thank you James Piorkowski for your mentorship and encouragement, and Ken Meyer for challenging me to reach new heights. Your teaching and artistry inspire me daily. To my parents, Steve and Marge, I cannot express enough thanks for your love and support. And to my sisters, Lisa, Karen, Steph, and Amanda, thank you. -

What Classical Music Is (Not the Final Text, but a Riff on What

Rebirth: The Future of Classical Music Greg Sandow Chapter 4 – What Classical Music Is (not the final text, but a riff on what this chapter will say) In this chapter, I’ll try to define classical music. But why? Don’t we know what it is? Yes and no. We’re not going to confuse classical music with other kinds of music, with rock, let’s say, or jazz. But can we say how we make these distinctions? You’d think we could. And yet when we look at definitions of classical music—either formal ones, in dictionaries, or informal ones, that we’d deduce by looking around at the classical music world—we run into trouble. As we’ll see, these definitions imply that classical music is mostly old music (and, beyond that, old music only of a certain kind). And they’re full of unstated assumptions about classical music’s value. These assumptions, working in the background of our thoughts, make it hard to understand what classical music really is. We have to fight off ideas about how much better it might be than other kinds of music, ideas which—to people not involved with classical music, the very people we need to recruit for our future audience—can make classical music seem intimidating, pompous, unconvincing. And so here’s a paradox. When we expose these assumptions, when we develop a factual, value-free definition of classical music, only then can we find classical music’s real value, and convincingly set out reasons why it should survive. [2] Let’s start with common-sense definition of classical music, the one we all use, without much thought, when we say we know what classical music is when we hear it. -

Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship Musicology and Ethnomusicology 11-2018 Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation University of Denver, "Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography" (2018). Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship. 20. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/20 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Musicology and Ethnomusicology at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography This bibliography is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/20 Cultural Appropriation in Classical Music: Annotated Bibliography Andrews, Jean. "Teresa Berganza's Re-appropriation of Carmen." Journal of Romance Studies 14, no. 1 (2014): 19-39. Andrews speaks on how to fix a history of appropriation. Much of classical repertoire comes from past, made in a time when the population had different sensibilities. t is unfair to hold the past to modern sensibilities. Though modern performances of these works can be slightly changed to combat this history of appropriation. Andrews analysis Teresa Berganza contribution in changing the role to adhere to a better cultural context. Birnbaum, Michael. "Jewish Music, German Musicians: Cultural Appropriation and the Representation of a Minority in the German Klezmer Scene." Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 54, no. -

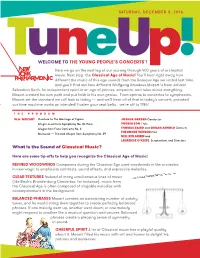

What Is the Sound of Classical Music? WELCOME to THE

Life on Tour in the Classical Age of Music During the 18th century it was fashionable for wealthy young men to finish their education with a grand tour of Europe’s SATURDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2016 cultural capitals. Exposure to art, languages, and artifacts developed young minds and their knowledge of the world. Mozart was just 7 years old when he set off on his first grand tour with his parents and sister, designed as an opportunity to showcase young Wolfgang and sister Nannerl’s talents. What might it be like to go on tour in the 1760s? TRAVEL CHALLENGES The Mozart family traveled about 2,500 miles — In addition to carriage breakdowns, which meant delays for the distance from New York to Los Angeles — in a days while repairs were being made, the cold chill during the cramped, unheated, incredibly bumpy carriage. rides led to lots of illness. Rheumatic fever, tonsillitis, scarlet TM Travels by boat across rivers and the sea were fever, and typhoid fever were experienced by Mozart family WELCOME TO THE YOUNG PEOPLE’S CONCERTS ! equally unpleasant! members, who were bedridden for weeks at a time. TuneUp! Here we go on the next leg of our journey through 400 years of orchestral LODGING HIGHLIGHTS music. Next stop: the Classical Age of Music! You’ll hear right away how The family stayed everywhere from a cramped Wolfgang and Nannerl performed for some of Europe’s most different the music of this age sounds from the Baroque Age we visited last time. three-room apartment above a barber shop to distinguished royalty and at some of the world’s loveliest Buckingham palace! palaces. -

Classical Music

CONSEJERÍA DE EDUCACIÓN Dirección General de Participación e Innovación Educativa Identificación del material AICLE TÍTULO Classical Music NIVEL LINGÜÍSTICO A2.1 SEGÚN MCER IDIOMA Inglés ÁREA / MATERIA Música NÚCLEO TEMÁTICO Historia de la Música La unidad pretende introducir al alumnado en el conocimiento de la música del GUIÓN TEMÁTICO clasicismo, trabajando sus características principales, los géneros vocales e instrumentales de la época y los compositores más destacados. FORMATO Material didáctico en formato PDF CORRESPONDENCIA 2º de Educación Secundaria CURRICULAR AUTORÍA Almudena Viéitez Roldán TEMPORALIZACIÓN 6 sesiones. APROXIMADA Competencia lingüística: - Adquisición de vocabulario - Elaborar y formular preguntas al compañero - Discusión y puesta en común en voz alta de aspectos concretos del tema - Elaboración de textos - Lectura comprensiva COMPETENCIAS - Fomento de las destrezas orales BÁSICAS Competencia cultural y artística: - Conocimiento de música de otras épocas, inculcando una actitud de respeto hacia la misma Competencia para aprender a aprender: - Extraer características a partir de audiciones - Extraer información de textos y ordenarla cronológicamente - Establecer similitudes y diferencias entre diversos tipos de obras Se recomienda completar la unidad con la interpretación vocal o instrumental de OBSERVACIONES alguna pieza de música del clasicismo; también sería recomendable el visionado de un fragmento de alguna ópera clásica. Material AICLE. 2º de ESO: Classical Music 3 Tabla de programación AICLE - Comprender y expresarse en una o más lenguas extranjeras de manera apropiada - Conocer, valorar y respetar los aspectos básicos de la cultura y la historia propias y OBJETIVOS de los demás, así como el patrimonio artístico y cultural - Apreciar la creación artística y comprender el lenguaje de las distintas manifesta- ciones artísticas, utilizando diversos medios de expresión y representación CONTENIDOS Bloque 4: La música en la cultura y en la sociedad. -

The Possessive Investment in Classical Music

S even The Possessive Investment in Classical Music CONFRONT I N G L E G A C I E S O F W HI TE SUPREMAC Y I N U . S . S C H OOLS AND DEPARTMENTS OF MUS I C Loren Kajikawa In the interrelationships of its musics, the Music Building paral- lels only imperfectly the twentieth-century world of musics. But in its juxtaposition of the central classical repertory to satellite styles deemed less significant, it reflects the modern world more explicitly in the sociocultural sense—the relationship of a domi- nant culture to its satellites or of a major power to third-world colonies. 1 B runo nettl Three music school anecdotes: A young rap artist is a student at College. She has been writing songs and recording in her bedroom studio since middle school. Although she is beginning to attract the attention of other artists and fans across the country, she is majoring in journalism and doesn’t see any reason to be involved with the music department. A recent PhD in ethnomusicology is hired by the School of Music at University as an adjunct instructor. His job is to teach courses in popular and world music that enroll well and bring much-needed tuition dollars to the school. Although his work is essential to the school, he remains on a year-to-year contract while professors teaching about classical music receive tenure and make twice his salary. The gospel choir is one of the most popular ensembles in the Department of Music at College. The director of the group, an African American, appears alongside her students in brochures touting the 155 vitality of the institution. -

Critical Theory for Musicology Conference Jan 12-13, 2018

Emily Doolittle Critical Theory for Musicology Conference Jan 12-13, 2018 I’m a composer, not a musicologist, and I’m often surprised when I catch glimpses of the antagonism that so often seems to arise between “new musicology” and “traditional musicology”.* Of course context matters, and of course notes matter, and of course the interactions between context and notes matter – as I’m sure everyone here will agree. I often find myself wanting to mediate between random musicologists on the internet! Although I’m continually arguing for the value of both “new” and “traditional” musicology, I didn’t realize until recently the extent to which I had nonetheless internalized the idea that there is some kind of inherent opposition between the music that “new musicologists” might find interesting, and the music that “traditional musicologists” consider worthy of study. I’m a composer, and a woman, and for as long as I’ve been a composer – 27 years now – I’ve been disturbed by the lack of representation of women composers. Of course I have many fantastic colleagues and friends who are women composers. When asked to suggest some interesting living composers, I often find that my list is half women or more – without any intention on my part to preferentially list women. But when it comes to textbooks, to music histories, to the programming of major orchestras, to the cannon, women are almost completely absent. When women are included at all, it will be 3 pages out of 600. Or 2 pieces in an entire orchestral season. The included women usually come from musical dynasties – Clara Schumann, Fanny Mendelssohn, Lili Boulanger, Ruth Crawford Seeger. -

Why All the Fuss About Beethoven?

Why All the Fuss About Beethoven? Welcome everyone. I’m Bob Greenberg, Music Historian-in-Residence for San Francisco Perfor- mances, and the title of this BobCast is Why All the Fuss About Beethoven?. At the time I recorded this BobCast (okay, yes, podcast)—in June of 2020—we were precisely half-way through what was supposed to be a year-long celebration of Beethoven and his mu- sic, capped by his 250th birthday on December 16, 2020. Thanks to you-know-what, Beethoven’s most excellent birthday bash has been a belly-up bust, and I’m not talking about the Beethoven busts on our pianos that we so happily festooned with party hats last December. For months I have been advocating—tirelessly and tiresomely—that we stage the biggest “do-over” in music history, and that all of the Beethoven concerts, and lectures, and colloquia cancelled in 2020 be rescheduled for 2021. Among my contributions to the Beethoven-love-fest-that-has-yet-to-really-be is a 10 lecture, five-hour exploration of Beethoven’s life and psyche titledThe First Angry Man, which was re- leased on Audible in November, 2019. My intentions to hawk the course during the many lec- tures and talks I was scheduled to give this year have come to naught as have, obviously, those lectures and talks. So in the spirit of “do-over” I’m offering up a bit of Lecture One ofThe First An- gry Man as we seek to answer what is, I think, a good question: why all the fuss about Beethoven? Allow me, please, to first explain that title:The First Angry Man.