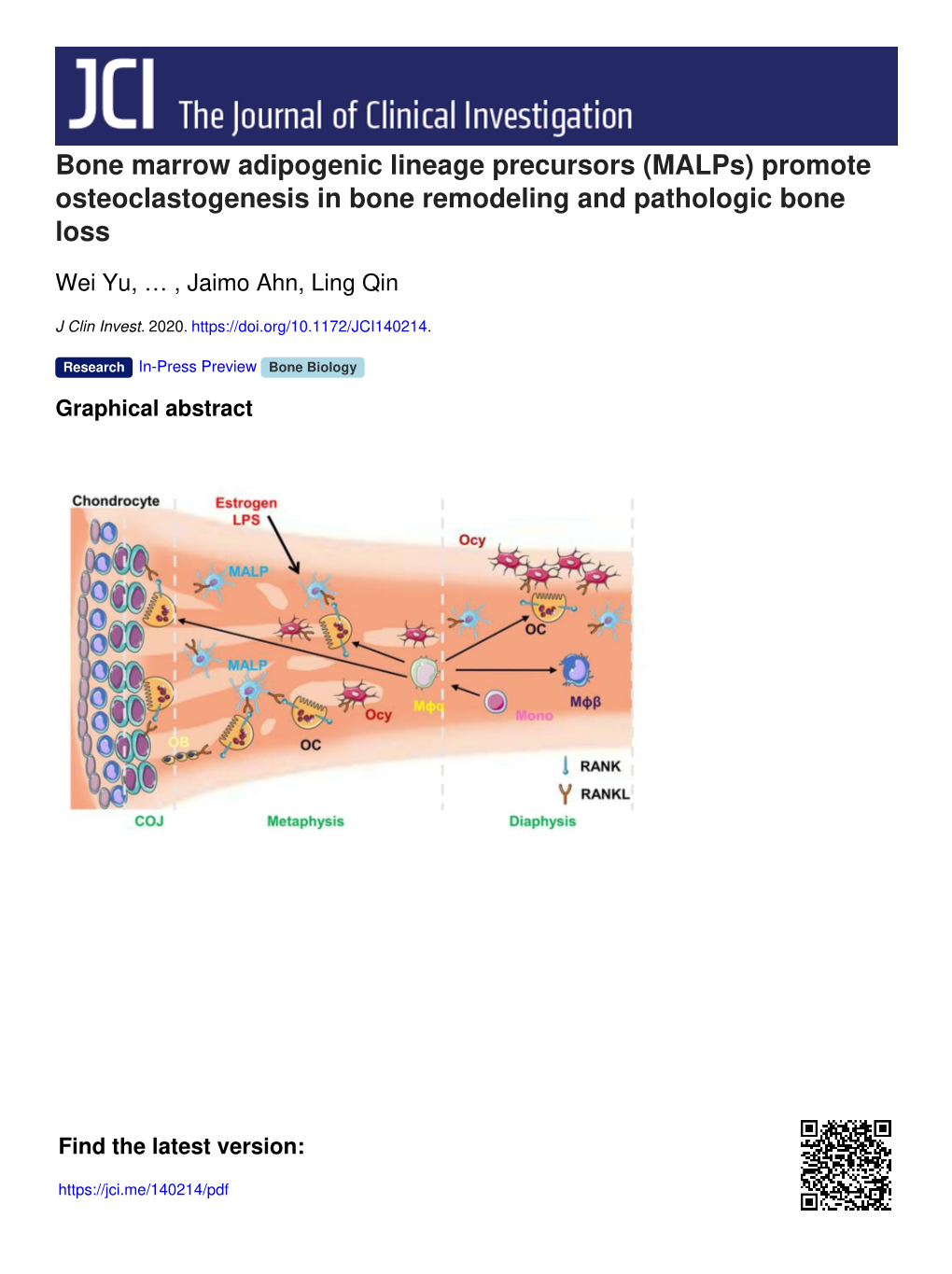

Bone Marrow Adipogenic Lineage Precursors (Malps) Promote Osteoclastogenesis in Bone Remodeling and Pathologic Bone Loss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ncf1 Affects Osteoclast Formation but Is Not Critical for Postmenopausal

Stubelius et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2016) 17:464 DOI 10.1186/s12891-016-1315-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Ncf1 affects osteoclast formation but is not critical for postmenopausal bone loss Alexandra Stubelius1*, Annica Andersson1, Rikard Holmdahl3, Claes Ohlsson2, Ulrika Islander1 and Hans Carlsten1 Abstract Background: Increased reactive oxygen species and estrogen deficiency contribute to the pathophysiology of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Reactive oxygen species contribute to bone degradation and is necessary for RANKL- induced osteoclast differentiation. In postmenopausal bone loss, reactive oxygen species can also activate immune cells to further enhance bone resorption. Here, we investigated the role of reactive oxygen species in ovariectomy- induced osteoporosis in mice deficient in Ncf1, a subunit for the NADPH oxidase 2 and a well-known regulator of the immune system. Methods: B10.Q wild-type (WT) mice and mice with a spontaneous point mutation in the Ncf1-gene (Ncf1*/*) were ovariectomized (ovx) or sham-operated. After 4 weeks, osteoclasts were generated ex vivo, and bone mineral density was measured using peripheral quantitative computed tomography. Lymphocyte populations, macrophages, pre-osteoclasts and intracellular reactive oxygen species were analyzed by flow cytometry. Results: After ovx, Ncf1*/*-mice formed fewer osteoclasts ex vivo compared to WT mice. However, trabecular bone mineral density decreased similarly in both genotypes after ovx. Ncf1*/*-mice had a larger population of pre- osteoclasts, whereas lymphocytes were activated to the same extent in both genotypes. Conclusion: Ncf1*/*-mice develop fewer osteoclasts after ovx than WT mice. However, irrespective of genotype, bone mineral density decreases after ovx, indicating that a compensatory mechanism retains bone degradation after ovx. -

Marrow Adipose Tissue Spectrum in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

176:1 I M de Araújo and others Marrow adipose tissue in 176:1 21–30 Clinical Study type 2 diabetes Marrow adipose tissue spectrum in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus Iana M de Araújo¹, Carlos E G Salmon², Andressa K Nahas³, Marcello H Nogueira-Barbosa¹, Jorge Elias Jr¹ and Francisco J A de Paula¹ Correspondence 1Department of Internal Medicine, Ribeirao Preto Medical School, 2Department of Physics, Faculty of should be addressed Philosophy, Sciences and Arts of Ribeirao Preto, and 3Department of Epidemiology, School of Public to F J A de Paula Health, USP, Ribeirão Preto, Sao Paulo,, Brazil Email [email protected] Abstract Objective: To assess the association of bone mass and marrow adipose tissue (MAT) with other fat depots, insulin resistance, bone remodeling markers, adipokines and glucose control in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Design and methods: The study groups comprised 24 controls (C), 26 obese (O) and 28 type 2 diabetes. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry was used to determine bone mineral density (BMD). Blood samples were collected for biochemical measurements. 1H Magnetic resonance spectroscopy was used to assess MAT in the L3 vertebra, and abdominal magnetic resonance imaging was used to assess intrahepatic lipids in visceral (VAT) and subcutaneous adipose tissue. Regression analysis models were used to test the association between parameters. Results: At all sites tested, BMD was higher in type 2 diabetes than in O and C subjects. The C group showed lower VAT values than the type 2 diabetes group and lower IHL than the O and type 2 diabetes groups. -

Formation of Osteoclast-Like Cells from Peripheral Blood of Periodontitis Patients Occurs Without Supplementation of Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor

J Clin Periodontol 2008; 35: 568–575 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01241.x Stanley T. S. Tjoa1, Teun J. de Formation of osteoclast-like cells Vries1,2, Ton Schoenmaker1,2, Angele Kelder3, Bruno G. Loos1 and Vincent Everts2 from peripheral blood of 1Department of Periodontology, Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), Universiteit van Amsterdam and Vrije periodontitis patients occurs Universteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; 2Department of Oral Cell Biology, Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), without supplementation of Universiteit van Amsterdam and Vrije Universteit, Amsterdam, Research Institute MOVE, The Netherlands; 3Department of Hematology, VUMC, Vrije Universiteit, macrophage colony-stimulating Amsterdam, The Netherlands factor Tjoa STS, de Vries TJ, Schoenmaker T, Kelder A, Loos BG, Everts V. Formation of osteoclast-like cells from peripheral blood of periodontitis patients occurs without supplementation of macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Periodontol 2008; 35: 568–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01241.x. Abstract Aim: To determine whether peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from chronic periodontitis patients differ from PBMCs from matched control patients in their capacity to form osteoclast-like cells. Material and Methods: PBMCs from 10 subjects with severe chronic periodontitis and their matched controls were cultured on plastic or on bone slices without or with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand (RANKL). The number of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive (TRACP1) multinucleated cells (MNCs) and bone resorption were assessed. Results: TRACP1 MNCs were formed under all culture conditions, in patient and control cultures. In periodontitis patients, the formation of TRACP1 MNC was similar for all three culture conditions; thus supplementation of the cytokines was not needed to induce MNC formation. -

Osteocyte Dysfunction Promotes Osteoarthritis Through MMP13-Dependent Suppression of Subchondral Bone Homeostasis

Bone Research www.nature.com/boneres ARTICLE OPEN Osteocyte dysfunction promotes osteoarthritis through MMP13-dependent suppression of subchondral bone homeostasis Courtney M. Mazur1,2, Jonathon J. Woo 1, Cristal S. Yee1, Aaron J. Fields 1, Claire Acevedo1,3, Karsyn N. Bailey1,2, Serra Kaya1, Tristan W. Fowler1, Jeffrey C. Lotz1,2, Alexis Dang1,4, Alfred C. Kuo1,4, Thomas P. Vail1 and Tamara Alliston1,2 Osteoarthritis (OA), long considered a primary disorder of articular cartilage, is commonly associated with subchondral bone sclerosis. However, the cellular mechanisms responsible for changes to subchondral bone in OA, and the extent to which these changes are drivers of or a secondary reaction to cartilage degeneration, remain unclear. In knee joints from human patients with end-stage OA, we found evidence of profound defects in osteocyte function. Suppression of osteocyte perilacunar/canalicular remodeling (PLR) was most severe in the medial compartment of OA subchondral bone, with lower protease expression, diminished canalicular networks, and disorganized and hypermineralized extracellular matrix. As a step toward evaluating the causality of PLR suppression in OA, we ablated the PLR enzyme MMP13 in osteocytes while leaving chondrocytic MMP13 intact, using Cre recombinase driven by the 9.6-kb DMP1 promoter. Not only did osteocytic MMP13 deficiency suppress PLR in cortical and subchondral bone, but it also compromised cartilage. Even in the absence of injury, osteocytic MMP13 deficiency was sufficient to reduce cartilage proteoglycan content, change chondrocyte production of collagen II, aggrecan, and MMP13, and increase the 1234567890();,: incidence of cartilage lesions, consistent with early OA. Thus, in humans and mice, defects in PLR coincide with cartilage defects. -

Bone Marrow (Stem Cell) Transplant for Sickle Cell Disease Bone Marrow (Stem Cell) Transplant

Bone Marrow (Stem Cell) Transplant for Sickle Cell Disease Bone Marrow (Stem Cell) Transplant for Sickle Cell Disease 1 Produced by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Departments of Hematology, Patient Education, and Biomedical Communications. Funds were provided by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, ALSAC, and a grant from the Plough Foundation. This document is not intended to take the place of the care and attention of your personal physician. Our goal is to promote active participation in your care and treatment by providing information and education. Questions about individual health concerns or specifi c treatment options should be discussed with your physician. For more general information on sickle cell disease, please visit our Web site at www.stjude.org/sicklecell. Copyright © 2009 St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital How did bone marrow (stem cell) transplants begin for children with sickle cell disease? Bone marrow (stem cell) transplants have been used for the treatment and cure of a variety of cancers, immune system diseases, and blood diseases for many years. Doctors in the United States and other countries have developed studies to treat children who have severe sickle cell disease with bone marrow (stem cell) transplants. How does a bone marrow (stem cell) transplant work? 2 In a person with sickle cell disease, the bone marrow produces red blood cells that contain hemoglobin S. This leads to the complications of sickle cell disease. • To prepare for a bone marrow (stem cell) transplant, strong medicines, called chemotherapy, are used to weaken or destroy the patient’s own bone marrow, stem cells, and infection fi ghting system. -

Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Treatments and Available Formulations

Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine (2020) 13:264–280 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-020-09624-0 STEM CELLS IN ORTHOPAEDIC SURGERY (J DRAGOO AND K JONES, SECTION EDITORS) Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Treatments and Available Formulations Kyle N. Kunze1 & Robert A. Burnett1 & Joshua Wright-Chisem2 & Rachel M. Frank3 & Jorge Chahla1 Published online: 23 April 2020 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020 Abstract Purpose of Review The use of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) has gained attention due to its potential to expedite healing and the ease of harvesting; however, clinical evidence is limited, and questions concerning optimal method of delivery and long-term outcomes remain unanswered. Recent Findings Administration of ADSCs in animal models has been reported to aid in improved healing benefits with enhanced repair biomechanics, superior gross histological appearance of injury sites, and higher concentrations of growth factors associated with healing compared to controls. Recently, an increasing body of research has sought to examine the effects of ADSCs in humans. Summary Several available processing techniques and formulations for ADSCs exist with evidence to suggest benefits with the use of ADSCs, but the superiority of any one method is not clear. Evidence from the most recent clinical studies available demonstrates promising outcomes following treatment of select musculoskeletal pathologies with ADSCs despite reporting variability among ADSCs harvesting and processing; these include (1) healing benefits and pain improvement for rotator cuff and Achilles tendinopathies, (2) improvements in pain and function in those with knee and hip osteoarthritis, and (3) improved cartilage regeneration for osteochondral focal defects of the knee and talus. -

Adaptive Immune Systems

Immunology 101 (for the Non-Immunologist) Abhinav Deol, MD Assistant Professor of Oncology Wayne State University/ Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit MI Presentation originally prepared and presented by Stephen Shiao MD, PhD Department of Radiation Oncology Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Disclosures Bristol-Myers Squibb – Contracted Research What is the immune system? A network of proteins, cells, tissues and organs all coordinated for one purpose: to defend one organism from another It is an infinitely adaptable system to combat the complex and endless variety of pathogens it must address Outline Structure of the immune system Anatomy of an immune response Role of the immune system in disease: infection, cancer and autoimmunity Organs of the Immune System Major organs of the immune system 1. Bone marrow – production of immune cells 2. Thymus – education of immune cells 3. Lymph Nodes – where an immune response is produced 4. Spleen – dual role for immune responses (especially antibody production) and cell recycling Origins of the Immune System B-Cell B-Cell Self-Renewing Common Progenitor Natural Killer Lymphoid Cell Progenitor Thymic T-Cell Selection Hematopoetic T-Cell Stem Cell Progenitor Dendritic Cell Myeloid Progenitor Granulocyte/M Macrophage onocyte Progenitor The Immune Response: The Art of War “Know your enemy and know yourself and you can fight a hundred battles without disaster.” -Sun Tzu, The Art of War Immunity: Two Systems and Their Key Players Adaptive Immunity Innate Immunity Dendritic cells (DC) B cells Phagocytes (Macrophages, Neutrophils) Natural Killer (NK) Cells T cells Dendritic Cells: “Commanders-in-Chief” • Function: Serve as the gateway between the innate and adaptive immune systems. -

Bone Marrow Biopsy

Helpline (freephone) 0808 808 5555 [email protected] www.lymphoma-action.org.uk Bone marrow biopsy This information is about a test called a bone marrow biopsy. You might have one to check if you have lymphoma in your bone marrow. On this page What is bone marrow? What is a bone marrow biopsy? Who might need one? Having a bone marrow biopsy Is a bone marrow biopsy safe? Getting the results We have separate information about the topics in bold font. Please get in touch if you’d like to request copies or if you would like further information about any aspect of lymphoma. Phone 0808 808 5555 or email [email protected]. What is bone marrow? Bone marrow is the spongy tissue in the middle of some of the bigger bones in your body, such as your thigh bone (femur), breastbone (sternum), hip bone (pelvis) and back bones (vertebrae). Your bone marrow is where blood cells are made. It contains cells called blood (‘haemopoietic’) stem cells. Stem cells are undeveloped cells that can divide and grow into all the blood cells you need. This includes red blood cells, platelets and all the different types of white blood cells. Page 1 of 8 © Lymphoma Action Figure: The different blood cells that develop in the bone marrow What is a bone marrow biopsy? A bone marrow biopsy is a test that involves taking a sample of bone marrow to be examined under a microscope. The samples are sent to a lab where an expert examines them. -

Osteocyte Differentiation and the Formation of an Interconnected Cellular Network in Vitro

EuropeanMJ Mc Garrigle Cells and et alMaterials. Vol. 31 2016 (pages 323-340) DOI: 10.22203/eCM.v031a21Formation of an interconnected osteocyte ISSN 1473-2262 network OSTEOCYTE DIFFERENTIATION AND THE FORMATION OF AN INTERCONNECTED CELLULAR NETWORK IN VITRO M.J. Mc Garrigle1, C.A. Mullen1, M.G. Haugh1, M.C. Voisin1 and L.M. McNamara1* 1 Centre for Biomechanics Research (BMEC), Biomedical Engineering, College of Engineering and Informatics, National University of Ireland, Galway Abstract Introduction Extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness and cell density can In bone, osteocyte cells form a complex three-dimensional regulate osteoblast differentiation in two dimensional (3D) communication network that plays a vital role in environments. However, it is not yet known how maintaining bone health by monitoring physical cues osteoblast-osteocyte differentiation is regulated within a arising during load-bearing activity and directing the 3D ECM environment, akin to that existing in vivo. In this activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts to initiate bone study we test the hypothesis that osteocyte differentiation is formation and resorption (Burger and Klein-Nulend, 1999). regulated by a 3D cell environment, ECM stiffness and cell Osteocytes are formed when cuboidal-like osteoblasts density. We encapsulated MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblastic cells become embedded within soft secreted osteoid and start to at varied cell densities (0.25, 1 and 2 × 106 cells/mL) within change morphologically to a dendritic shape characteristic microbial transglutaminase (mtgase) gelatin hydrogels of an osteocyte. This transition is accompanied by a loss of low (0.58 kPa) and high (1.47 kPa) matrix stiffnesses. of cell volume (reduced organelle content) (Knothe Tate Cellular morphology was characterised from phalloidin- et al., 2004; Palumbo et al., 2004) and an increase in the FITC and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) dilactate formation and elongation of thin cytoplasmic projections staining. -

Modeling Osteoclast Defect and Altered Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche in Osteopetrosis with Patient-Derived Ipscs

Modeling Osteoclast Defect and Altered Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche in Osteopetrosis with Patient-Derived iPSCs Inci Cevher Zeytin Hacettepe University Berna Alkan Hacettepe University: Hacettepe Universitesi Cansu Ozdemir Hacettepe University: Hacettepe Universitesi Duygu Cetinkaya Hacettepe University: Hacettepe Universitesi FATMA VISAL OKUR ( [email protected] ) Hacettepe University, Faculty of Medicine https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1679-6205 Research Keywords: Osteopetrosis, TCIRG1, iPSC, disease modeling, osteoclast, niche modeling, HSC Posted Date: March 9th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-258821/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/22 Abstract Background Patients with osteopetrosis present with defective bone resorption caused by the lack of osteoclast activity and hematopoietic alterations, but their bone marrow hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell and osteoclast contents might be different. Osteoclasts recently have been described as the main regulators of HSCs niche, however, their exact role remains controversial due to the use of different models and conditions. Investigation of their role in hematopoietic stem cell niche formation and maintenance in osteopetrosis patients would provide critical information about the mechanisms of altered hematopoiesis. We used patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to model osteoclast defect and hematopoietic niche compartments in vitro. Methods iPSCs were generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients carrying TCIRG1 mutation. iPSC lines were differentiated rst into hematopoietic stem cells-(HSCs), and then into myeloid progenitors and osteoclasts using a step-wise protocol. Then, we established different co-culture conditions with bone marrow-derived hMSCs and iHSCs of osteopetrosis patients as an in vitro hematopoietic niche model to evaluate the interactions between osteopetrotic-HSCs and bone marrow- derived MSCs as osteogenic progenitor cells. -

Adipocytes in Hematopoiesis and Acute Leukemia: Friends, Enemies, Or Innocent Bystanders?

Leukemia (2020) 34:2305–2316 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0886-x REVIEW ARTICLE Molecular targets for therapy Adipocytes in hematopoiesis and acute leukemia: friends, enemies, or innocent bystanders? 1 1 1 Julia Zinngrebe ● Klaus-Michael Debatin ● Pamela Fischer-Posovszky Received: 15 April 2020 / Revised: 15 May 2020 / Accepted: 21 May 2020 / Published online: 30 May 2020 © The Author(s) 2020. This article is published with open access Abstract The bone marrow is home to well-balanced normal hematopoiesis, but also the stage of leukemia’s crime. Marrow adipose tissue (MAT) is a unique and versatile component of the bone marrow niche. While the importance of MAT for bone health has long been recognized, its complex role in hematopoiesis has only recently gained attention. In this review article we summarize recent conceptual advances in the field of MAT research and how these developments impact our understanding of MAT regulation of hematopoiesis. Elucidating routes of interaction and regulation between MAT and cells of the hematopoietic system are essential to pinpoint vulnerable processes resulting in malignant transformation. The concept of white adipose tissue contributing to cancer development and progression on the cellular, metabolic, and systemic level is 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: generally accepted. The role of MAT in malignant hematopoiesis, however, is controversial. MAT is very sensitive to changes in the patient’s metabolic status hampering a clear definition of its role in different clinical situations. Here, we discuss future directions for leukemia research in the context of metabolism-induced modifications of MAT and other adipose tissues and how this might impact on leukemia cell survival, proliferation, and antileukemic therapy. -

Terminology Resource File

Terminology Resource File Version 2 July 2012 1 Terminology Resource File This resource file has been compiled and designed by the Northern Assistant Transfusion Practitioner group which was formed in 2008 and who later identified the need for such a file. This resource file is aimed at Assistant Transfusion Practitioners to help them understand the medical terminology and its relevance which they may encounter in the patient’s medical and nursing notes. The resource file will not include all medical complaints or illnesses but will incorporate those which will need to be considered and appreciated if a blood component was to be administered. The authors have taken great care to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate and up to date. Authors: Jackie Cawthray Carron Fogg Julia Llewellyn Gillian McAnaney Lorna Panter Marsha Whittam Edited by: Denise Watson Document administrator: Janice Robertson ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to acknowledge the following people for providing their valuable feedback on this first edition: Tony Davies Transfusion Liaison Practitioner Rose Gill Transfusion Practitioner Marie Green Transfusion Practitioner Tina Ivel Transfusion Practitioner Terry Perry Transfusion Specialist Janet Ryan Transfusion Practitioner Dr. Hazel Tinegate Consultant Haematologist Reviewed July 2012 Next review due July 2013 Version 2 July 2012 2 Contents Page no. Abbreviation list 6 Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) 7 Acidosis 7 Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) 7 Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome