Lipid Abnormalities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypocholesterolemia in Patients with Polycythemia Vera

J Clin Exp Hematopathol Vol. 52, No. 2, Oct 2012 Original Article Hypocholesterolemia in Patients with Polycythemia Vera Hiroshi Fujita,1) Tamae Hamaki,2) Naoko Handa,2) Akira Ohwada,2) Junji Tomiyama,2) and Shigeko Nishimura1) Polycythemia vera (PV) is characterized by low serum total cholesterol despite its association with vascular events such as myocardialand cerebralinfarction. Serum cholesterollevelhasnot been used as a diagnostic criterion for PV since the 2008 revision of the WHO classification. Therefore, we revisited the relationship between serum lipid profile, including total cholesterol level, and erythrocytosis. The medical records of 34 erythrocytosis patients (hemoglobin : men, > 18.5 g/dL ; women, > 16.5 g/dL) collected between August 2005 and December 2011 were reviewed for age, gender, and lipid profiles. The diagnoses of PV and non-PV erythrocytosis were confirmed and the in vitro efflux of cholesterol into plasma in whole blood examined. The serum levels of total cholesterol, low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-Ch), and apolipoproteins A1 and B were lower in PV than in non-PV patients. The in vitro release of cholesterol into the plasma was greater in PV patients than in non-PV and non-polycythemic subjects. Serum total cholesterol, LDL-Ch, and apolipoproteins A1 and B levels are lower in patients with PV than in those with non-PV erythrocytosis. The hypocholesterolemia associated with PV may be attributable to the sequestration of circulating cholesterol into the increased number of erythrocytes. 〔J Clin Exp Hematopathol 52(2) : 85-89, 2012〕 Keywords: polycythemia vera, JAK2 V617F mutation, hypocholesterolemia rocytosis without the JAK2 V167F mutation.5 Although the INTRODUCTION serum cholesterol level in PV patients has been studied Polycythemia vera (PV) is classified as a myeloprolifera- previously,6 it has not been used as a diagnostic criterion for tive neoplasm and usually occurs in people aged 60-79 years. -

The Nuclear Envelope in Lipid Metabolism and Pathogenesis of NAFLD

biology Review The Nuclear Envelope in Lipid Metabolism and Pathogenesis of NAFLD Cecilia Östlund 1,2, Antonio Hernandez-Ono 1 and Ji-Yeon Shin 1,* 1 Department of Medicine, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032, USA; [email protected] (C.Ö.); [email protected] (A.H.-O.) 2 Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-212-305-4088 Received: 9 September 2020; Accepted: 12 October 2020; Published: 15 October 2020 Simple Summary: The liver is a major organ regulating lipid metabolism and a proper liver function is essential to health. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a condition with abnormal fat accumulation in the liver without heavy alcohol use. NAFLD is becoming one of the most common liver diseases with the increase in obesity in many parts of the world. There is no approved cure for the disease and a better understanding of disease mechanism is needed for effective prevention and treatment. The nuclear envelope, a membranous structure that surrounds the cell nucleus, is connected to the endoplasmic reticulum where the vast majority of cellular lipids are synthesized. Growing evidence indicates that components in the nuclear envelope are involved in cellular lipid metabolism. We review published studies with various cell and animal models, indicating the essential roles of nuclear envelope proteins in lipid metabolism. We also discuss how defects in these proteins affect cellular lipid metabolism and possibly contribute to the pathogenesis of NAFLD. -

Fat Accumulation in Enterocytes: a Key to the Diagnosis of Abetalipoproteinemia Or Homozygous Hypobetalipoproteinemia

Cases and Techniques Library (CTL) E223 Fat accumulation in enterocytes: a key to the diagnosis of abetalipoproteinemia or homozygous hypobetalipoproteinemia Fig. 3 Microscopic image showing vacuo- lization, especially on the top of the villi. Vacuolization causes a paler aspect because of fat dissolving during the process of embed- ding the tissue in par- affin wax (“empty” vacuoles instead of fat accumulation). Fig. 4 Negative peri- Fig. 1 A 20-year-old woman was referred by odic acid-Schiff staining her ophthalmologist to investigate the reason shows no microorgan- for her hypovitaminosis A and secondary night isms nor accumulation blindness. A macroscopic image taken during of glycogen, supporting gastroscopy shows a pale duodenal mucosa. the assumption that the vacuolization is due to lipid accumulation. level of detection). Her level of 25-hydroxy These findings suggested a diagnosis of Fig. 2 Videocapsule image illustrating the vitamin D appeared to be normal, but at either abetalipoproteinemia or homo- pale yet pronounced aspect of the villi. the time of her first admission, vitamin D zygous hypolipobetaproteinemia, disor- substitution had already been started. A ders that are caused by mutations in both This document was downloaded for personal use only. Unauthorized distribution is strictly prohibited. slightly raised alanine aminotransferase alleles of the microsomal triglycerides A 20-year-old woman was referred by her was also detected (33U/L). transfer protein (MTP) or in the APO-B ophthalmologist to investigate the reason Further work-up excluded cystic fibrosis, gene, respectively [1–2] This results in for her hypovitaminosis A and secondary exocrine pancreas insufficiency, and celiac the failure of APO B-100 synthesis in the night blindness. -

Pharmacogenomics Variability of Lipid-Lowering Therapies in Familial Hypercholesterolemia

Journal of Personalized Medicine Review Pharmacogenomics Variability of Lipid-Lowering Therapies in Familial Hypercholesterolemia Nagham N. Hindi 1,†, Jamil Alenbawi 1,† and Georges Nemer 1,2,* 1 Division of Genomics and Translational Biomedicine, College of Health and Life Sciences, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Doha P.O. Box 34110, Qatar; [email protected] (N.N.H.); [email protected] (J.A.) 2 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, American University of Beirut, Beirut DTS-434, Lebanon * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +974-445-41330 † Those authors contributed equally to the work. Abstract: The exponential expansion of genomic data coupled with the lack of appropriate clinical categorization of the variants is posing a major challenge to conventional medications for many common and rare diseases. To narrow this gap and achieve the goals of personalized medicine, a collaborative effort should be made to characterize the genomic variants functionally and clinically with a massive global genomic sequencing of “healthy” subjects from several ethnicities. Familial- based clustered diseases with homogenous genetic backgrounds are amongst the most beneficial tools to help address this challenge. This review will discuss the diagnosis, management, and clinical monitoring of familial hypercholesterolemia patients from a wide angle to cover both the genetic mutations underlying the phenotype, and the pharmacogenomic traits unveiled by the conventional and novel therapeutic approaches. Achieving a drug-related interactive genomic map will potentially benefit populations at risk across the globe who suffer from dyslipidemia. Citation: Hindi, N.N.; Alenbawi, J.; Nemer, G. Pharmacogenomics Variability of Lipid-Lowering Keywords: familial hypercholesterolemia; pharmacogenomics; PCSK9 inhibitors; statins; ezetimibe; Therapies in Familial novel lipid-lowering therapy Hypercholesterolemia. -

Seme Protocolos051115.Pages

PROTOCOLOS DE PRÁCTICA CLÍNICA EN MEDICINA ESTÉTICA FEBRERO 2016 COMITÉ EDITORIAL Dra. Petra Mª Vega López. Presidenta de la SEME. Dra. Pilar Rodrigo Anoro. Presidenta de Honor de la SEME. Dra. Paloma Tejero. Socia de Honor de la SEME. Dr. Juan Antonio López López-Pitalúa. Vicepresidente 1º de la SEME. Dr. Fernando García Monforte. Vicepresidente 2º de la SEME. Dr. Manuel Sánchez Sánchez. Tesorero de la SEME. SOCIEDAD ESPAÑOLA DE MEDICINA ESTETICA Ronda General Mitre, 210.08006 Barcelona. E-mail [email protected] 3ª Edición Febrero de 2016 Dirección editorial: Dr. Antoni Baena Coordinación editorial: Mónica Rivero > página 3 > página 4 PRESENTACIÓN Los Protocolos de Práctica Clínica en Medicina Estetica son una iniciativa de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Estética, publicados por primera vez en febrero de 2008, ampliados, revisados y actualizados en febrero de 2015. Los objetivos de los mismos son: • Homogeneizar los criterios de la práctica clínica: las nomenclaturas, las clasificaciones y los tratamientos. • Aplicar la medicina basada en la evidencia. • Dotar a la Medicina Estética de una herramienta que mejore la seguridad del paciente y que facilite la actuación del profesional. Es la primera iniciativa internacional de este tipo en Medicina Estética y a través de estos protocolos la SEME quiere ofrecer al médico y a la sociedad la posibilidad de: • Facilitar el Desarrollo Profesional Continuo en beneficio de los ciudadanos. • Ofrecer una herramienta médico-legal que proteja al ciudadano y facilite la labor del profesional. • Ser una guía de actuación que fomente la buena práctica médica y que minimice los efectos adversos. > página 5 MARZO 2015 > página 6 ÍNDICE 1. -

WO 2014/018979 Al 30 January 2014 (30.01.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/018979 Al 30 January 2014 (30.01.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: Cambridge Center #7024C, Cambridge, MA 02142 (US). C07C 233/80 (2006.01) A61K 31/167 (2006.01) LEWIS, Michael; 7 Cambridge Center #7024C, Cam C07C 237/42 (2006.01) bridge, MA 02142 (US). (21) International Application Number: (74) Agents: ELRIFI, Ivor, R. et al; Mintz Levin Cohn Ferris PCT/US2013/052572 Glovsky And Popeo, P.C., One Financial Center, Boston, MA 021 11 (US). (22) International Filing Date: 29 July 2013 (29.07.2013) (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, (25) Filing Language: English AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (26) Publication Language: English BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (30) Priority Data: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 61/676,496 27 July 2012 (27.07.2012) US KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (71) Applicants: THE BROAD INSTITUTE, INC. [US/US]; MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, 7 Cambridge Center #7024c, Cambridge, MA 02142 (US). OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, THE GENERAL HOSPITAL CORPORATION d/b/a SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL [US/US]; TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Hypocholesterolemia in Clinically Serious Conditions – Review

Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2008, 152(2):181–189. 181 © P. Vyroubal, C. Chiarla, I. Giovannini, R. Hyspler, A. Ticha, D. Hrnciarikova, Z. Zadak HYPOCHOLESTEROLEMIA IN CLINICALLY SERIOUS CONDITIONS – REVIEW Pavel Vyroubala*, Carlo Chiarlab, Ivo Giovanninib, Radek Hysplera, Alena Tichaa, Dana Hrnciarikovaa, Zdenek Zadaka a Department of Gerontology and Metabolism, Faculty Hospital and Faculty of Medicine in Hradec Kralove, Sokolska 581, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic b Centro de Studio per la fi ssiopatologia, Université Cattolica del S.Cuore, L.go A.Gemelli 8-00168 Roma, Italy e-mail: [email protected] Received: October 21, 2008; Accepted (with revisions): August 5, 2008 Key words: Cholesterol/Hypocholesterolemia/Hypolipoproteinemia/SIRS/Cytokines/Polytrauma/ Sepsis/Critically ill Background: Cholesterol is an essential component of cell membranes, precursor of steroids, biliary acids and other components of serious importance in live organism. Cholesterol synthesis is a complicated and energy-demand- ing process. Real daily need of cholesterol and mechanisms of decline cholesterol levels in critical ill are unknown. During stressful situations a signifi cant hypocholesterolaemia may be found. Hypocholesterolemia has been known for a number of years to be a signifi cant prognostic indicator of increased morbidity and mortality connected with a whole spectrum of pathological conditions. The aim of article is the elucidation of the role and importance of hypo- cholesterolaemia during the intensive care. Methods and Results: We examined studies that are engaged in problems of hypocholesterolemia in critically ill. Very low levels of total as well as LDL cholesterol are most frequently found in serious polytrauma, after extensive surgery, in serious infections, in protracted hypovolemic shock. -

Hypocholesterolemia and Dysregulated Production of Angiopoietin-Like Proteins in Sickle Cell Anemia Patients T

Cytokine 120 (2019) 88–91 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cytokine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cytokine Hypocholesterolemia and dysregulated production of angiopoietin-like proteins in sickle cell anemia patients T Felipe Vendramea, Leticia Olopsa, Sara Teresinha Olalla Saada, Fernando Ferreira Costaa, ⁎ Kleber Yotsumoto Fertrina,b, a Hematology and Hemotherapy Center, University of Campinas – UNICAMP, Campinas, Brazil b Division of Hematology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Angiopoietin-like proteins (ANGPTL) are responsible for inhibiting lipoprotein lipase activity, and ANGPTL3 and Atherosclerosis ANGPTL4 deficiencies have been shown to lower lipoprotein levels in animal models and in humans carrying Sickle cell disease loss-of-function mutations. Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is a hereditary hemolytic anemia characterized by vaso- Cholesterol occlusive crises and end-organ damage, which is curiously associated with hypocholesterolemia and a low in- Hemolysis cidence of atherosclerosis, whose underlying mechanisms are unclear. We hypothesized that ANGPTL3 and Dyslipidemia ANGPTL4 dysregulation is responsible for the hypolipidemic phenotype in SCA. We measured circulating con- centrations of ANGPTL3 and ANGPTL4 and correlated them with hemolytic biomarkers and lipoproteins in 40 patients with SCA and 30 control individuals. The association between hemolysis and low cholesterol levels in SCA was confirmed along with surprisingly higher levels of ANGPTL3 and ANGPTL4 in SCA patients than in controls. ANGPTL3 correlated with hemolysis markers LDH and reticulocyte counts, while ANGPTL4 did not. Our data show a paradoxical increase in production of ANGPTL3 and ANGPTL4 in SCA, which would be ex- pected to cause hyperlipidemia, due to increased inhibition of lipoprotein lipase. ANGPTL3, exclusively pro- duced by the liver, correlated with hemolysis markers, suggesting a possible hepatic response to hemolysis. -

Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma with Scleroderma

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma With Scleroderma Glenn G. Russo, MD GOAL To understand the presentation and treatment of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this activity, dermatologists and general practitioners should be able to: 1. Explain the laboratory and histopathology results in NXG. 2. Discuss the theoretical pathogenesis of NXG. 3. Describe the treatment options for NXG. CME Test on page 317. This article has been peer reviewed and Medicine is accredited by the ACCME to provide approved by Michael Fisher, MD, Professor of continuing medical education for physicians. Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Albert Einstein College of Medicine designates Review date: November 2002. this educational activity for a maximum of 1.0 hour This activity has been planned and implemented in category 1 credit toward the AMA Physician’s in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies Recognition Award. Each physician should claim of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical only those hours of credit that he/she actually spent Education through the joint sponsorship of Albert in the educational activity. Einstein College of Medicine and Quadrant This activity has been planned and produced in HealthCom, Inc. The Albert Einstein College of accordance with ACCME Essentials. Dr. Russo reports no conflict of interest. The author reports off-label use of the following medications: extracorporeal photophoresis, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, nitrogen mustard, adrenocorticotropic hormone, azathioprine, radiation therapy, plasmapheresis, hydroxychloroquine, thalidomide, and etretinate. Dr. Fisher reports no conflict of interest. I report the case of a 68-year-old man who pre- exposure to cold temperatures. This is an interest- sented with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) ing constellation of findings in this rare disorder with concomitant scleroderma, along with the pres- that raises questions concerning its pathogenesis. -

Familial Hypercholesterolemia Panel, Sequencing

Familial Hypercholesterolemia Panel, Sequencing Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is the most common inherited cardiovascular disease. It is characterized by markedly elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) in the absence of an apparent secondary cause and premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular Tests to Consider disease (ASCVD). Manifestations include coronary artery disease (CAD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), angina, myocardial infarction, xanthomas, and corneal arcus. Those with one Familial Hypercholesterolemia Panel, parent with FH have a 50% chance of inheriting the condition, known as heterozygous FH Sequencing 3002110 (HeFH or FH). Method: Massively Parallel Sequencing Use to conrm a diagnosis of FH. Homozygous FH (HoFH) is a less common but more severe disorder, resulting from biallelic variants in a dominant FH-associated gene. If both parents have FH, their offspring have a Familial Mutation, Targeted Sequencing 50% chance of having HeFH and a 25% chance of HoFH, which results from receiving two 2001961 altered chromosomes. HoFH is characterized by severe early-onset CAD, aortic stenosis, Method: Polymerase Chain Reaction/Sequencing and a high rate of coronary bypass surgery or death by teenage years. Treatment of FH Use for cascade screening of at-risk relatives commonly includes statins or lipid-lowering therapy with lifestyle modications. FH is when a causative sequence variant has designated as a tier-1 genetic disorder by the CDC with proven benet for case identication previously been identied in a family member and family-based cascade screening. 1 with FH. A copy of the relative's genetic laboratory Molecular testing may be used to conrm a diagnosis of FH in symptomatic individuals or report documenting the familial variant is for identication of at-risk relatives to ensure treatment prior to onset of ASCVD. -

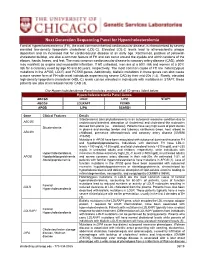

Hypercholesterlemia Information Sheet 6-10-19

Next Generation Sequencing Panel for Hypercholesterolemia Clinical Features: Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), the most common inherited cardiovascular disease, is characterized by severly elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). Elevated LDL-C levels lead to atherosclerotic plaque deposition and an increased risk for cardiovascular disease at an early age. Xanthomas, patches of yellowish cholesterol buildup, are also a common feature of FH and can occur around the eyelids and within tendons of the elbows, hands, knees, and feet. The most common cardiovascular disease is coronary artery disease (CAD), which may manifest as angina and myocardial infarction. If left untreated, men are at a 50% risk and women at a 30% risk for a coronary event by age 50 and 60 years, respectively. The most common cause of FH are heterozygous mutations in the APOB, LDLR, and PCSK9 genes. Additionally, biallelic mutations in these genes can also cause a more severe form of FH with most individuals experiencing severe CAD by their mid-20s (1,2). Rarely, elevated high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels can be elevated in individuals with mutations in STAP1, these patients are also at increased risk for CAD (3). Our Hypercholesterolemia Panel includes analysis of all 10 genes listed below. Hypercholesterolemia Panel Genes ABCG5 LDLR LIPC STAP1 ABCG8 LDLRAP1 PCSK9 APOB LIPA SCARB1 Gene Clinical Features Details Sitosterolemia (aka phytosterolemia) is an autosomal recessive condition due to ABCG5 unobstructed intestinal absorption of cholesterol and cholesterol-like molecules derived from plants (i.e. – sitosterol). Patients have very high levels of plant sterols Sitosterolemia in plasma and develop tendon and tuberous xanthomas (knee, heel, elbow) in ABCG8 childhood, premature atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease [OMIM# 210250]. -

Hypocholesterolemia

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS h INTERNAL MEDICINE/CLINICAL PATHOLOGY h PEER REVIEWED Hypocholesterolemia Julie Allen, BVMS, MS, MRCVS, DACVIM (SAIM), DACVP Cornell University FOR MORE Following are differential Find more Differential Diagnosis lists in diagnoses, listed in upcoming issues of order of likelihood, for Clinician’s Brief and on patients presented with cliniciansbrief.com hypocholesterolemia. h Panting h Hypercholesterolemia h Hypoalbuminemia h Severe icterus (false decrease) References h Neutropenia h Protein-losing enteropathy (eg, Center SA, Magne ML. Historical, physical h Decreased Total examination, and clinicopathologic lymphangiectasia, inflammatory features of portosystemic vascular Thyroxine Semin Vet bowel disease, lymphoma, anomalies in the dog and cat. h Increased Total Med Surg (Small Anim). 1990;5(2):83-93. Thyroxine infectious agents such as Moore PF. A review of histiocytic diseases of dogs and cats. Vet Pathol. h Hypoglycemia Heterobilharzia americana) 2014;51(1):167-184. h Epistaxis h Liver disease such as Pirro M, Ricciuti B, Rader DJ, et al. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and h Regurgitation portosystemic shunt, ductal cancer: marker or causative? Prog Lipid plate malformation, or liver Res. 2018;71:54-69. Simmerson SM, Armstrong PJ, failure (eg, secondary to toxins Wünschmann A, et al. Clinical features, such as Sago palm) intestinal histopathology, and outcome in protein-losing enteropathy in h Hypoadrenocorticism Yorkshire Terrier dogs. J Vet Intern Med. h Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency 2014;28(2):331-337. Soare T, Noble PJ, Hetzel U, Fonfara S, h Hemophagocytic syndrome; Kipar A. Paraneoplastic syndrome in can be seen in association with haemophagocytic histiocytic sarcoma in a dog. J Comp Pathol. 2012;146(2- a variety of infectious and 3):168-174.