Co-Operative Ties and the Impact of External Factors Upon Innovation In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Industrial Heritage, Tourism and Old Industrial Buildings: Charting the Difficult Path from Redundancy to Heritage Attraction

RESEARCH Cutting Edge 1997 Industrial heritage, tourism and old industrial buildings: charting the difficult path from redundancy to heritage attraction Rick Ball, Staffordshire University ISBN 0-85406-864-3 INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE, TOURISM AND OLD INDUSTRIAL BUILDINGS: CHARTING THE DIFFICULT PATH FROM REDUNDANCY TO HERITAGE ATTRACTION Dr. Rick Ball Division of Geography Staffordshire University Leek Road Stoke-on-Trent ST4 2DF UK Abstract This exploratory paper considers the processes, problems and constraints involved in the transition of old industrial buildings, often those prone to vacancy, into heritage and tourism- linked uses. It discusses the heritage-property nexus with regard to industrial buildings, and builds an empirical picture of such relationships in a specific local property arena. The discussion is partly based on research projects completed in a number of localities within the British West Midlands. In particular, it draws on work on the evaluation of European Commission Community Initiatives in the West Midlands that have targetted tourism development, as well as on EPSRC funded research focused on vacant industrial buildings in Stoke-on-Trent. As such, in scene-setting style, a structure is developed for the evaluation of heritage-property links with the emphasis on the small number of specific local projects that have at least partly sought to bring buildings back into use with some, perhaps extensive, degree of heritage activity in mind. 1. Heritage and the property domain - some introductory comments The background to this paper is the apparent reassertion of industrial heritage as a flavour of tourism in the late 1990s (Goodall, 1996), a process pursued with vigour in the quest for the renaissance of the urban industrial economy (see Ball and Stobart, 1996). -

Clubhouse Network Newsletter Issue

PLEASE Clubhouse Network TAKE ONE Newsletter THEY’RE FREE Hello everyone, this is the twenty-first edition of the Clubhouse Network Newsletter made by volunteers and customers of the Clubhouse Community. Thanks to everyone who made contributions to this issue. We welcome any articles or ideas from Clubhouse customers. Chinese New Year celebrations took place at the City Museum and Art Gallery on 10th February. Members went along and joined in the fun. Things to enjoy included the dancing Chinese dragon, fire- crackers, traditional music, and a children’s theatre. Dragons are of course legendary animals, but they are important to Chinese people who think of dragons as helpful, friendly creatures. They are linked to good luck, long life and wisdom. The Dragon in the dance has features of other animals such as the horns of a stag, the scales of a fish Music, craft and mask making were being and the footpads of a tiger. demonstrated by talented artisans and musicians. Have fun with this Sudoku Puzzle! 2 Recovery Assistance Dogs This month Sasha talks about her life as Vicky’s assistance dog: I am Sasha and I am a Jack Russell cross and I am nine years old. I help my owner Vicky with getting out of our home. When we are together I help my owner to not panic going out to Clubhouse or mixing with people. My owner struggles with depression and anxiety and when together I help keep her calm. I’ll soon have passed my Level 1 ‘paw test’ so I can go to many more places. -

N C C Newc Coun Counc Jo Castle Ncil a Cil St Oint C E-Und Nd S Tatem

Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council Statement of Community Involvement Joint Consultation Report July 2015 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 Regulations Page 3 Consultation Page 3 How was the consultation on Page 3 the Draft Joint SCI undertaken and who was consulted Main issues raised in Page 7 consultation responses on Draft Joint SCI Main changes made to the Page 8 Draft Joint SCI Appendices Page 12 Appendix 1 Copy of Joint Page 12 Press Release Appendix 2 Summary list of Page 14 who was consulted on the Draft SCI Appendix 3 Draft SCI Page 31 Consultation Response Form Appendix 4 Table of Page 36 Representations, officer response and proposed changes 2 Introduction This Joint Consultation Report sets out how the consultation on the Draft Newcastle-under- Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council Statement of Community Involvement (SCI) was undertaken, who was consulted, a summary of main issues raised in the consultation responses and a summary of how these issues have been considered. The SCI was adopted by Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council on the 15th July 2015 and by Stoke-on-Trent City Council on the 9th July 2015. Prior to adoption, Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council respective committees and Cabinets have considered the documents. Newcastle-under- Lyme Borough Council’s Planning Committee considered a report on the consultation responses and suggested changes to the SCI on the 3RD June 2015 and recommended a grammatical change at paragraph 2.9 (replacing the word which with who) and this was reported to DMPG on the 9th June 2015. -

Companies Referred to in the Ceramic and Allied Trades Union Collection

Companies referred to in the Ceramic and Allied Trades Union Collection Note - The following is a list of the companies which can be clearly identified in the CATU archive without any risk of confusion, the evidence coming from headed letter paper or something equally unassailable. This list is for information only. We can not retrieve documents from the collection from this list as the documents are spread throughout the collection in different files and have not been indexed. Many documents in the archive are much less clear cut (hand written notes, surveys etc) and it is not always easy to identify precisely which company is being referred to. One frequent potential source of confusion is that potbanks often had their own names, and these may sometimes look like company names. In practice, potbanks could change hands or be divided between more than one company. List of Companies in alphabetical order A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P R S T V W A Wm. Adams & Sons Ltd Greenfield Pottery/ Greengates Pottery, Tunstall Adderleys Ltd Daisy Bank, Longton Alcock, Lindley & Bloore Ltd Shelton Alexandra Pottery Burslem Allertons Ltd Longton C. Amison & Co Ltd Longton Armitage Shanks Ltd Barrhead; Kilmarnock Armitage Ware Ltd Armitage Sanitary Pottery Geo. L. Ashworth & Bros Ltd Hanley Ault Potteries Ltd Swadlincote Ault & Tunnicliff Ltd Swadlincote H. Aynsley & Co Ltd Longton John Aynsley & Sons Ltd Longton Top of page B Barker Bros Ltd Meir Works, Longton Barlows (Longton) Ltd Belleek Pottery Ltd Belleek, Co. Fermanagh Beswick & Sons Longton Biltons (1912) Ltd Stoke Blythe Colour Works Ltd Cresswell, Stoke Blythe Porcelain Co Longton T. -

Potteries Auctions Catalogue 13 Jan 2018

Potteries Auctions Catalogue 13 Jan 2018 1 Total Gym XL branded weight bench (no weights). 20th Cent oak occasional table and two modern £10.00 - £20.00 pine bedside cabinets (5) £15.00 - £30.00 2 CleanAirBlue Adblue Diesel SCR Fuel 10 litre 70 A selection of chairs to include - a pair of drum £5.00 - £10.00 Knightsbridge high backed armchairs (pine 3 OKO Off Road Tyre Sealant 25L Drum £20.00 - frames) along with a Lloyd Loom style chair in £40.00 white, and a 20th cent. parlour chair (4) £20.00 - £40.00 4 Boxed 61 key Power play electronic keyboard together with M&S classic stone raclette(2) 71 A selection of 20th cent. Oak chairs to include 7 ladderback dining chairs (two carver chairs) plus 5 Distressed Metal travel trunk with brass lock two others (9) £20.00 - £40.00 £10.00 - £20.00 72 Two small oak tables. (2) £10.00 - £20.00 6 A large mixed collection of Civil Engineering items to include a designer aluminium radiator, two 73 A mid century Pine table. £25.00 - £50.00 wooden window frames, Pyronix passive infered 74 A reproduction Oak nest of three tables along with detectors, detective working glasses, scaffolding a G-Plan nest of three tables with tiled tops. (2) clamps, outdoor plastic pipe clamps, Sat 1&2 TV £25.00 - £50.00 outlets and short male support pipes, part vehicle 75 Two pine side cabinets. (2) £20.00 - £40.00 roof bars. £10.00 - £20.00 77 Modern leatherette kingsize bed frame and slats. -

Potteries-Appreciation-Vol-2-Master

1 The Potteries and Surrounding Areas Part 2: Appreciating The Region Barry J Bridgwood and Ingval Maxwell Information Box: Structured Approach Supplementing the COTAC Regional Study The Potteries and Surrounding Areas Part 1: Understanding the Region, the following approach considers key aspects that created The Potteries and sets out to construct a deeper appreciation of them through short statements, Information Boxes and related illustrations, whilst raising some pertinent questions Reading Part 1: Understanding the Region along with this Part 2: Appreciating the Region will provide guidance and information to help suggest answers to the questions Various summary Information Boxes [in grey tinted inserts] are offered in each of the five sections alongside Summary Questions [in coloured inserts], whilst suggested answers are offered as an Annex to the volume Council on Training in Architectural Conservation (COTAC) COTAC originated in 1959 in response to the need for training resources for practitioners so they could properly specify and oversee work involved in repairing and conserving historic buildings and churches. Since its inception the Charity has persistently and influentially worked to lift standards, develop training qualifications and build networks across the UK’s conservation, repair and maintenance (CRM) sector, estimated at over 40% of all construction industry activities. This has involved working partnerships with national agencies, professional and standard setting bodies, educational establishments and training interests. This study is directed towards a general audience and those wishing to increase their knowledge of The Potteries area, and its specific form and type of buildings in addition to assisting in providing a framework for carrying out similar regional studies. -

10700887.Pdf

Business structure, busines culture, and the industrial district : The Potteries, c. 1850- 1900. POPP, Andrew Derek Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/3099/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/3099/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. agfBCSMSS lX 585 586 5 Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10700887 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10700887 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 BUSINESS STRUCTURE, BUSINESS CULTURE. AND THE INDUSTRIAL DISTRICT: THE POTTERIES, c.1850-1900. -

Ashmolean Papers Ashmolean Papers

ASHMOLEAN PAPERS ASHMOLEAN PAPERS 2017 1 Preface 2 Introduction: Obsolescence and Industrial Culture Tim Strangleman 10 Topographies of the Obsolete: Exploring the Site Specific and Associated Histories of Post Industry Neil Brownsword and Anne Helen Mydland 18 Deindustrialisation and Heritage in Three Crockery Capitals Maris Gillette 50 Industrial Ruination and Shared Experiences: A Brief Encounter with Stoke-on-Trent Alice Mah 58 Maintenance, Ruination and the Urban Landscape of Stoke-on-Trent Tim Edensor 72 Image Management Systems: A Model for Archiving Stoke-on-Trent’s Post-Industrial Heritage Jake Kaner 82 Margins, Wastes and the Urban Imaginary Malcolm Miles 98 Biographies Topographies of the Obsolete: Ashmolean Papers Preface First published by Topographies of the Obsolete Publications 2017. ISBN 978-82-690937 In The Natural History of Staffordshire,1 Dr Robert Plot, the first keeper of the Unless otherwise specified the Copyright © for text and artwork: Ashmolean Museum describes an early account of the county’s pre-industrial Tim Strangleman, Neil Brownsword, Anne Helen Mydland, Maris Gillette, Alice Mah, pottery manufacturing during the late 17th century. Apart from documenting Tim Edensor, Jake Kaner, Malcolm Miles potters practices and processes, Plot details the regions natural clays that were once fundamental to its rise as a world renowned industrial centre for ceramics. Edited by Neil Brownsword and Anne Helen Mydland Designed by Phil Rawle, Wren Park Creative Consultants, UK Yet in recent decades the factories and communities of labour that developed Printed by The Printing House, UK around these natural resources have been subject to significant transition. Global economics have resulted in much of the regions ceramic industry outsourcing Designed and published in Stoke-on-Trent to low-cost overseas production. -

Service Directory

Service Directory Version 15: December 2018 This directory is managed and updated by the Programme Team. Email any: changes, amendments, updates or additions to: [email protected] Organisations/services are grouped into categories and can be accessed directly from the contents page with one click. 1 Contents Principles .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Vision ......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 TRAINING SERVICES ................................................................................................................................... 7 Expert Citizens C.I.C ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Olive Branch (Staffordshire Fire and Rescue Service) .................................................................................................... 7 Safeguarding Children Partnership Board ...................................................................................................................... 8 Voices ............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 SERVICES AND SUPPORT ...................................................................................................................... -

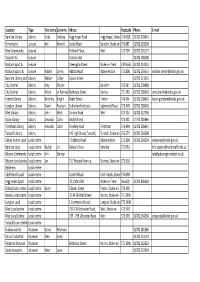

Walks Distribution List

Location Type First name Surname Adress Postcode Phone E‐mail Bentilee Library Library Vicky Embrey Fegg Hayes Road Fegg Hayes, Stoke‐ ST6 6QR, 01782 878843 Dimensions Leisure Neil Morrell Scotia Road Burslem, Stoke‐on‐ ST6 4ET 01782 233500 Meir Community Leisure Pickford Place, Meir ST3 7DY 01782 235177 Tourist Info Leisure Victoria Hall 01782 236000 Wallace Sport & Leisure Greengate Street Stoke‐on‐Trent GST6 6BL 01782 234333 Wallace Sports & Leisure Robert James Abbots Road Abbey Hulton ST2 8DU 01782 233555 [email protected] Burslem Library and Library William Colley Queen Street 01782 231315 City Central Library Amy Shutler Burslem ST6 3EF 01782 238488 City Central Library Alison or Patricia Bethesda Street Hanley ST1 3RS 01782 238410 [email protected] Fenton Library Library Beverley Knight Baker Street Fenton ST4 3AF 01782 238419 [email protected]; Longton Library Library Dawn Poulson Sutherland Institute Lightwood Road, ST3 4HY 01782 238426 Meir Library Library John West Sandon Road Meir ST3 7DJ 01782 312706 Stoke Library Library Amanda Carin Wolfe Street, ST4 4SZ 01782 238446 Trentham Library Library Amanda Carin Trentley Road Trentham ST4 8PH 01782 238447 Tunstall Library Library 142 High Street, Tunstall, Tunstall, Stoke‐on‐ ST6 5TP 01782 236598 Abbey Hulton Local Local centre 71 Abbots Road Abbey Hulton ST2 8DU 01782 234234 [email protected] Bentilee Local Local centre Rachel Liz Dalwish Drive Bentilee ST2 0EU [email protected] Blurton Community Local centre Kim Stanyer [email protected] -

Our Moment to Shine Main Image: the London 2012 Olympic Torch

Stoke-on-Trent - Our Moment to Shine Main image: The London 2012 Olympic Torch Top left image: Olympics past Traditional Staffordshire oatcakes and present Bottom left image: Emma Jackson - 800m Olympic hopeful at The City of Stoke-on-Trent Sports Personality of the Year Awards 2012 Middle right image: Imran Sherwani at the 1988 Seoul Olympics My family and I have always Hockey Final against West Germany Image courtesy of Staffordshire News & Media been warmly welcomed by the City of Stoke-on-Trent, Bottom right image: Councillor Mohammed Pervez and having run a business Leader - Stoke-on-Trent City Council selling the city's favourite newspaper at the heart of the community I would not recommend anywhere else in the world. “It is home to the friendliest and most welcoming people on earth and that comes from someone who has travelled the world. I also have been given the honour of carrying the Torch through my city. What an honour and what a city!" "Come on Stoke!" Imran Sherwani - a member of the gold medal winning Great Britain and Northern Ireland squad at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul against West Germany. warm welcome to visitors joining us in Stoke-on-Trent to celebrate hosting the Olympic Torch Relay and Evening Celebration Event. I could have moved away to A a different area of the UK for Our city will swell with pride concert. For four years, the Moorcroft, Steelite International This brochure gives a flavour university, somewhere with as the eyes of the world follow Stoke-on-Trent stage of the and Dudson - to name but a few of the people, companies and more athletics facilities for the symbolic Flame through Tour of Britain event has drawn - attracting visitors and buyers organisations which make our example, but I chose to stay our historic streets.... -

ENTER & VIEW REPORT Wedgwood Unit, Stadium Court

ENTER & VIEW REPORT Wedgwood Unit, Stadium Court Residential & Nursing Home Date & Time of Visit The visit took place on Wednesday 7th December 2016 at 10:30 a.m. Name of Service Provider & Premises Visited Bupa – Wedgwood Unit, Stadium Court Residential & Nursing Home, Greyhound Way, ST6 3LL. Tel: 01782 207979 Registered Home Manager Name Mr. Adam Moore Authorised Representatives Jean Mayer, Phil Leese, Dave Rushton All Team members have undertaken specific Enter & View training and are Disclosure and Barring Service Checked. Reasons & Purpose for the Visit Healthwatch Stoke-on-Trent, in partnership with the City Council, has introduced a Dignity and Respect Charter which applies to every resident receiving care. Our visit is to assess how this is perceived by both residents and staff; The recent change in use from residential to nursing care within the Wedgwood Unit has prompted a visit so that we may meet residents and staff working here. Overview of the Wedgwood Unit The Wedgwood Unit has recently changed use and now provides beds and short stay care for residents no longer requiring a bed at the acute hospital (University Hospital of North Midlands). It is anticipated that residents here will stay for periods of between 4 and 8 weeks during which time they will undergo physiotherapy and other services to ensure they are able to go home at the end of the stay. A Quality Assurance Team based at the UHNM monitors the service to ensure that any issues relating to admission and transfer arrangements are shared and resolved. There is careful monitoring of all activity including readmissions.