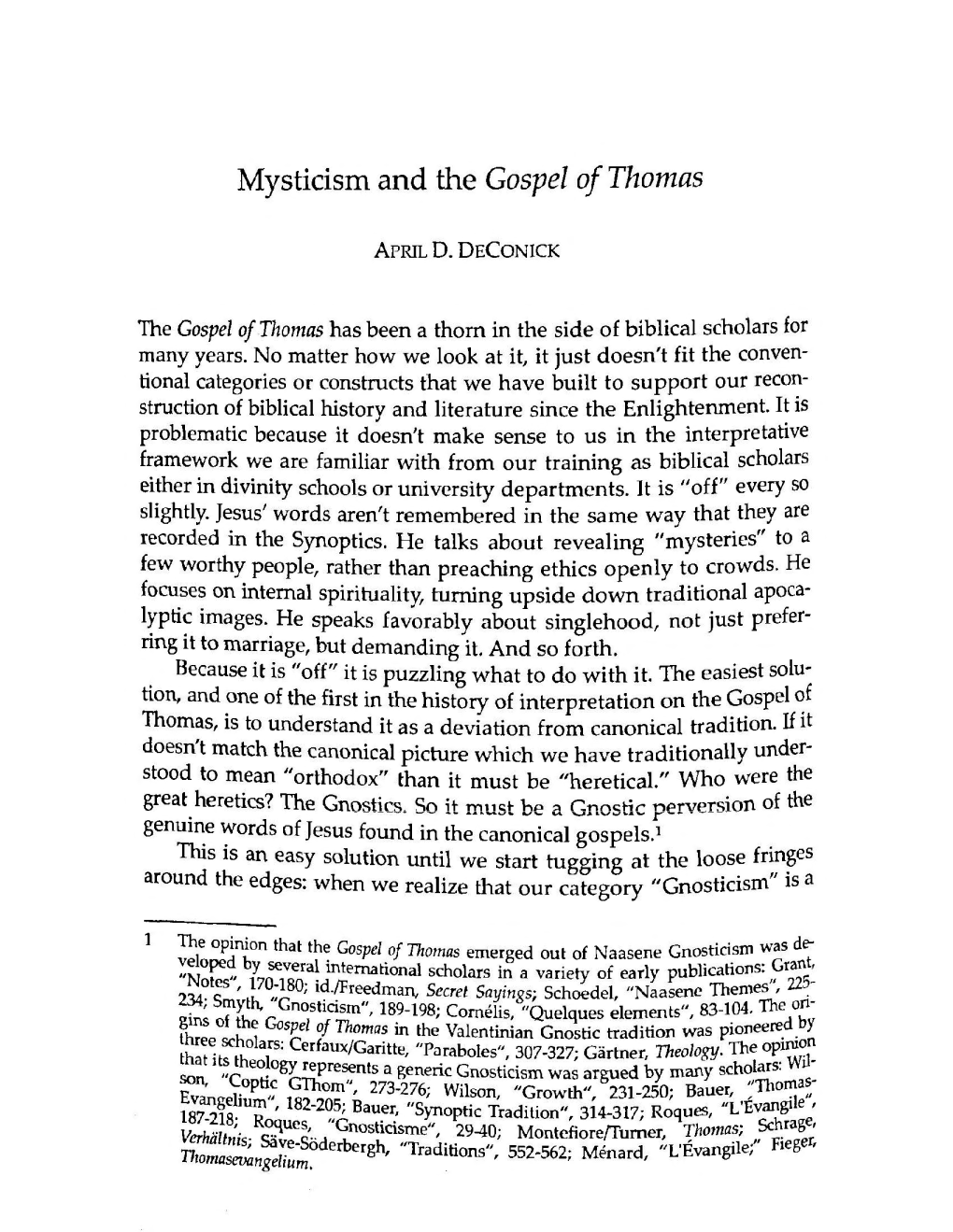

Mysticism and the Gospel of Thomas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relationship Between Spirituality and Wisdom

DISSERTATION PROTECTIVE FACTORS AGAINST ALCOHOL ABUSE IN COLLEGE STUDENTS: SPIRITUALITY, WISDOM, AND SELF-TRANSCENDENCE Submitted by Sydney E. Felker Department of Psychology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2011 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Kathryn M. Rickard Co-Advisor: Richard M. Suinn Lisa Miller Thao Le Copyright by Sydney E. Felker 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT PROTECTIVE FACTORS AGAINST ALCOHOL ABUSE IN COLLEGE STUDENTS: SPIRITUALITY, WISDOM, AND SELF-TRANSCENDENCE Past research consistently suggests that spirituality is a protective factor against substance abuse in adolescents and adults. Many other personality and environmental factors have been shown to predict alcohol abuse and alcohol-related problems, yet much of the variance in alcohol abuse remains unexplained. Alcohol misuse continues to plague college campuses in the United States and recent attempts to reduce problematic drinking have fallen short. In an effort to further understand the factors contributing to students’ alcohol abuse, this study examines how spirituality, wisdom, and self- transcendence impact the drinking behaviors of college students. Two groups of students were studied: 1. students who were mandated for psychoeducational and clinical intervention as a result of violating the university alcohol policy; 2. a comparison group of students from the general undergraduate population who had never been sanctioned for alcohol misuse on campus. Alcohol use behaviors were assessed through calculating students’ reported typical blood alcohol level and alcohol-related problems. Results showed that wisdom is significantly and negatively related to blood alcohol level and alcohol-related problems for the mandated group but not the comparison group. -

Solomon Reflects on the Meaning of Life

SESSION 11 Solomon Reflects on the Meaning of Life SESSION SUMMARY In this session, we are going to align ourselves with Solomon and ask some of the same questions he asked. As we pose these questions together, we should look for their resolution in the person and work of Jesus Christ. Knowing that God exists, we can experience a life of meaning, justice, and purpose. We also call others to seek answers to their questions by looking to Christ. SCRIPTURE Ecclesiastes 1:1-11; 3:16–4:3; 12:9-14 106 Leader Guide / Session 11 THE POINT Because God exists, life has meaning and purpose. INTRO/STARTER 5-10 MINUTES Option 1 What do you think of when you hear the word vanity? The term vanity can refer to breath, emptiness, something temporary, or meaninglessness. Throughout the Book of Ecclesiastes, Solomon used a from of this word at least 24 times. Solomon used this phrasing to demonstrate the meaninglessness of living life apart from God. The term vanity of vanities is a superlative, emphasizing the emptiness of a Godless life. Without God, life is empty, holds no real meaning, and provides no lasting significance. He showed that only God can add real meaning to life. • Does life seem meaningless to you? Why or why not? Believers do not have to go through life wondering if they have purpose or meaning. God brings purpose and meaning to life. Sometimes that feeling of hopelessness still seeps in. But a vibrant relationship with the Lord enables people to view their lives in a more positive way. -

1.1 Biblical Wisdom

JOB, ECCLESIASTES, AND THE MECHANICS OF WISDOM IN OLD ENGLISH POETRY by KARL ARTHUR ERIK PERSSON B. A., Hon., The University of Regina, 2005 M. A., The University of Regina, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2014 © Karl Arthur Erik Persson, 2014 Abstract This dissertation raises and answers, as far as possible within its scope, the following question: “What does Old English wisdom literature have to do with Biblical wisdom literature?” Critics have analyzed Old English wisdom with regard to a variety of analogous wisdom cultures; Carolyne Larrington (A Store of Common Sense) studies Old Norse analogues, Susan Deskis (Beowulf and the Medieval Proverb Tradition) situates Beowulf’s wisdom in relation to broader medieval proverb culture, and Charles Dunn and Morton Bloomfield (The Role of the Poet in Early Societies) situate Old English wisdom amidst a variety of international wisdom writings. But though Biblical wisdom was demonstrably available to Anglo-Saxon readers, and though critics generally assume certain parallels between Old English and Biblical wisdom, none has undertaken a detailed study of these parallels or their role as a precondition for the development of the Old English wisdom tradition. Limiting itself to the discussion of two Biblical wisdom texts, Job and Ecclesiastes, this dissertation undertakes the beginnings of such a study, orienting interpretation of these books via contemporaneous reception by figures such as Gregory the Great (Moralia in Job, Werferth’s Old English translation of the Dialogues), Jerome (Commentarius in Ecclesiasten), Ælfric (“Dominica I in Mense Septembri Quando Legitur Job”), and Alcuin (Commentarius Super Ecclesiasten). -

Wisdom Literature

Wisdom Literature What is Wisdom Literature? “Wisdom literature” is the generic label for the books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes (=Qoheleth) and Job in the Hebrew Bible. Two other major wisdom books, the Book of Ben Sira (=Ecclesiasticus) and the Wisdom of Solomon, are found in the Apocrypha, but are accepted as canonical in the Catholic tradition. Some psalms (e.g. 1, 19, 119) are regarded as “wisdom psalms” by analogy with the main wisdom books, and other similar writings are found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. The label derives simply from the fact that “wisdom” and “folly” are discussed frequently in these books. The designation is an old one, going back at least to St. Augustine. Wisdom is instructional literature, in which direct address is the norm. It may consist of single sentences, proverbial or hortatory, strung together, or of longer poems and discourses, some of which tend toward the philosophical. From early times, wisdom was associated with King Solomon. According to 1 Kings 4:29-34, God gave Solomon very great wisdom, discernment, and breadth of understanding as vast as the sand on the sea-shore, so that Solomon’s wisdom surpassed the wisdom of all the people of the east, and all the wisdom of Egypt . .He composed three thousand proverbs, and his songs numbered a thousand and five. He would speak of trees, from the cedar that is in the Lebanon to the hyssop that grows in the wall; he would speak of trees, from the cedar that is in the Lebanon to the hyssop that grows in the wall; he would speak of animals, and birds, and reptiles, and fish. -

Gospel of Thomas Is the Most Important Manuscript Discovery Ever Made

Introduction For those interested in Jesus of Nazareth and the origins of Christianity, the Gospel of Thomas is the most important manuscript discovery ever made. Apart from the canonical scriptures and a few scattered sayings, the Gospel of Thomas is our only historically valuable source for the teach- ings of Jesus. Although it has been available in European languages since the 1950s, it is still subject to intense scrutiny and debate by biblical schol- ars. The Gospel of Thomas is roughly the same age as the canonical New Testament gospels, but it contains sayings of Jesus that present very dif- ferent views on religion and on the nature of humanity and salvation, and it thereby raises the question whether the New Testament’s version of Jesus’ teachings is entirely accurate and complete. In late 1945, an Egyptian peasant named Mohammed Ali al-Samman Mohammad Khalifa rode his camel to the base of a cliff, hoping to find fertilizer to sell in the nearby village of Nag Hammadi. He found, instead, a large sealed pottery jar buried in the sand. He feared it might contain a genie that would haunt or attack him, and he hoped it might contain a treasure. Gathering his courage, he smashed open the jar and discov- ered only a collection of twelve old books. Suspecting that they might have value on the antiquities market, he kept the books and eventually sold them for a small sum. The books gradually came into the hands of scholars in Cairo, Europe, and America. Today those books are known as the Nag Hammadi library, a collection that is generally considered to be the most important archaeological discovery of the twentieth cen- tury for research into the New Testament and early Christianity. -

Practical Wisdom

© Michael Lacewing Practical wisdom The syllabus defines practical wisdom as ‘the capacity to make informed, rational judgements without recourse to a formal decision procedure’. Many deontological theories argue that there is no formal decision procedure, and in fact even Kant, who has a formal decision procedure, argues that applying the Categorical Imperative correctly involves ‘judgment’, which cannot be formalized. However, the idea of practical wisdom is today most strongly associated with Aristotle, so we shall focus our discussion on his view of how to make moral decisions. Practical wisdom (Greek phronesis; sometimes translated ‘prudence’), says Aristotle, is ‘a true and reasoned state of capacity to act with regard to the things that are good or bad for man’ Nicomachean Ethics VI.5). So while practical wisdom involves knowledge of what is good or bad, it is not merely theoretical knowledge, but a capacity to act on such knowledge as well. This capacity requires 1. a general conception of what is good or bad, which Aristotle relates to the conditions for human flourishing; 2. the ability to perceive, in light of that general conception, what is required in terms of feeling, choice, and action in a particular situation; 3. the ability to deliberate well; and 4. the ability to act on that deliberation. Aristotle’s theory makes practical wisdom very demanding. The type of insight into the good that is needed and the relation between practical wisdom and virtues of character are both complex. Practical wisdom cannot be taught, but requires experience of life and virtue. Only the person who is good knows what is good, according to Aristotle. -

30 Days of Praying the Names and Attributes Of

30 Days of Praying the 1 God is Jehovah. 2 God is Jehovah-M’Kad- 3 God is infinite. The name of the independent, desh. God is beyond measure- self-complete being—“I AM This name means “the ment—we cannot define Him WHO I AM”—only belongs God who sanctifies.” A God by size or amount. He has no Names and Attributes of God to Jehovah God. Our proper separate from all that is evil beginning, no end, and no response to Him is to fall down requires that the people who limits. Though God is infinitely far above our ability to fully understand, He tells us through the Scriptures very specific truths in fear and awe of the One who follow Him be cleansed from —Romans 11:33 about Himself so that we can know what He is like, and be drawn to worship Him. The following is a list of 30 names possesses all authority. all evil. and attributes of God. Use this guide to enrich your time set apart with God by taking one description of Him and medi- —Exodus 3:13-15 —Leviticus 20:7,8 tating on that for one day, along with the accompanying passage. Worship God, focusing on Him and His character. 4 God is omnipotent. 5 God is good. 6 God is love. 7 God is Jehovah-jireh. 8 God is Jehovah-shalom. 9 God is immutable. 10 God is transcendent. This means God is all-power- God is the embodiment of God’s love is so great that He “The God who provides.” Just as “The God of peace.” We are All that God is, He has always We must not think of God ful. -

WISDOM (Tlwma) and Pffllosophy (FALSAFA)

WISDOM (tLWMA) AND PfflLOSOPHY (FALSAFA) IN ISLAMIC THOUGHT (as a framework for inquiry) By: Mehmet ONAL This thcsis is submitted ror the Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Wales - Lampeter 1998 b"9tr In this study the following two hypothesisare researched: 1. "WisdotW' is the fundamental aspect of Islamic thought on which Islamic civilisation was established through Islamic law (,Sharfa), theology (Ldi-M), philosophy (falsafq) and mysticism (Surism). 2. "Due to the first hypothesis Islamic philosophy is not only a commentary on the Greek philosophy or a new form of Ncoplatonism but a native Islamic wisdom understandingon the form of theoretical study". The present thesis consists of ten chaptersdealing with the concept of practical wisdom (Pikmq) and theoretical wisdom (philosophy or falsafa). At the end there arc a gcncral conclusion,glossary and bibliography. In the introduction (Chapter One) the definition of wisdom and philosophy is establishedas a conceptualground for the above two hypothesis. In the following chapter (Chapter Two) I focused on the historical background of these two concepts by giving a brief history of ancient wisdom and Greek philosophy as sourcesof Islamic thought. In the following two chapters (Chapter Three and Four) I tried to bring out a possibledefinition of Islamic wisdom in the Qur'5n and Sunna on which Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), theology (A-alim), philosophy (falsafq) and mysticism (Sufism) consistedof. As a result of the above conceptual approaching,I tried to reach a new definition for wisdom (PiLma) as a method that helps in the establishmentof a new Islamic way of life and civilisation for our life. -

The Correlation Between Theology and Worship

Running head: THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP The Correlation Between Theology and Worship Tyler Thompson A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2018 THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 1 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Rick Jupin, D.M.A. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Keith Cooper, M.A. Committee Member ______________________________ David Wheeler, P.H.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Chris Nelson, M.F.A. Assistant Honors Director THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 2 ______________________________ Date Abstract This thesis will address the correlation between theology and worship. Firstly, it will address the process of framing a worldview and how one’s worldview influences his thinking. Secondly, it will contrast flawed views of worship with the biblically defined worship that Christ calls His followers to practice. Thirdly, it will address the impact of theology in the life of a believer and its necessity and practice in the lifestyle of a worship leader. THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 3 The Correlation Between Worship and Theology Introduction Since creation, mankind was designed to devote its heart, soul, and mind to the Sovereign God of all (Rom. 1:18-20). As an outward sign of this commitment and devotion, mankind would live in accordance with the established, inerrant, and absolute truths of God (Matt. 22:37, John 17:17). Unfortunately, as a consequence of man’s disobedience, many beliefs have arisen which tempt mankind to replace God’s absolute truth as the basis of their worldview (Rom. -

The Fifth Gospel. the Gospel of Thomas Comes Of

The Fifth Gospel NEWI ED TION The Fifth Gospel The Gospel of Thomas Comes of Age NEWI ED TION Stephen J. Patterson With an essay by James M. Robinson And a New revised translation from Hans-Gebhard Bethge, et al. Published by T&T Clark International A Continuum Imprint The Tower Building, 80 Maiden Lane, 11 York Road, Suite 704, London SE1 7NX New York, NY 10038 www.continuumbooks.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. © Stephen J. Patterson, Hans-Gebhard Bethge, James M. Robinson 2011 Stephen J. Patterson, Hans-Gebhard Bethge and James M. Robinson have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the Author of this work. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-567-31084-2 Typeset by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NN Contents Introduction Stephen J. Patterson vii CHAPTER 1 Revised English Translation 1 CHAPTER 2 Understanding the Gospel of Thomas Today 26 CHAPTER 3 The Story of the Nag Hammadi Library 67 Further Reading 97 Notes 100 General Index 118 Index of Gospel of Thomas References 126 Index of Biblical References 128 Introduction Stephen J. Patterson The Gospel of Thomas ranks among the most important manuscript discoveries in the last two hundred years. The debate it unleashed in the 1950s, when scholars first got a glimpse of the new gospel, continues unabated today. -

Nag Hammadi, Gnosticism and New Testament Interpretation

Grace Theological Journal 8.2 (1987) 195-212 Copyright © 1987 by Grace Theological Seminary. Cited with permission. NAG HAMMADI, GNOSTICISM AND NEW TESTAMENT INTERPRETATION WILLIAM W. COMBS The Gnostic heresy alluded to in the NT and widely repudiated by Christian writers in the second century and after has been in- creasingly studied in the last forty years. The discovery in upper Egypt of an extensive collection of Gnostic writings on papyri trans- formed a poorly known movement in early Christianity into a well documented heresy of diverse beliefs and practices. The relationship of Gnosticism and the NT is an issue that has not been resolved by the new documents. Attempts to explain the theology of the NT as dependent on Gnostic teachings rest on ques- tionable hypotheses. The Gnostic redeemer-myth cannot be docu- mented before the second century: Thus, though the Gnostic writings provide helpful insight into the heresies growing out of Christianity, it cannot be assumed that the NT grew out of Gnostic teachings. * * * INTRODUCTION STUDENTS of the NT have generally been interested in the subject of Gnosticism because of its consistent appearance in discussions of the "Colossian heresy" and the interpretation of John's first epistle. It is felt that Gnosticism supplies the background against which these and other issues should be understood. However, some who use the terms "Gnostic" and "Gnosticism" lack a clear understanding of the movement itself. In fact, our knowledge of Gnosticism has suffered considerably from a lack of primary sources. Now, however, with the discovery of the Nag Hammadi (hereafter, NH) codices, this void is being filled. -

What Is Philosophy.Pdf

I N T R O D U C T I O N What Is Philosophy? CHAPTER 1 The Task of Philosophy CHAPTER OBJECTIVES Reflection—thinking things over—. [is] the beginning of philosophy.1 In this chapter we will address the following questions: N What Does “Philosophy” Mean? N Why Do We Need Philosophy? N What Are the Traditional Branches of Philosophy? N Is There a Basic Method of Philo- sophical Thinking? N How May Philosophy Be Used? N Is Philosophy of Education Useful? N What Is Happening in Philosophy Today? The Meanings Each of us has a philos- “having” and “doing”—cannot be treated en- ophy, even though we tirely independent of each other, for if we did of Philosophy may not be aware of not have a philosophy in the formal, personal it. We all have some sense, then we could not do a philosophy in the ideas concerning physical objects, our fellow critical, reflective sense. persons, the meaning of life, death, God, right Having a philosophy, however, is not suffi- and wrong, beauty and ugliness, and the like. Of cient for doing philosophy. A genuine philo- course, these ideas are acquired in a variety sophical attitude is searching and critical; it is of ways, and they may be vague and confused. open-minded and tolerant—willing to look at all We are continuously engaged, especially during sides of an issue without prejudice. To philoso- the early years of our lives, in acquiring views phize is not merely to read and know philoso- and attitudes from our family, from friends, and phy; there are skills of argumentation to be mas- from various other individuals and groups.