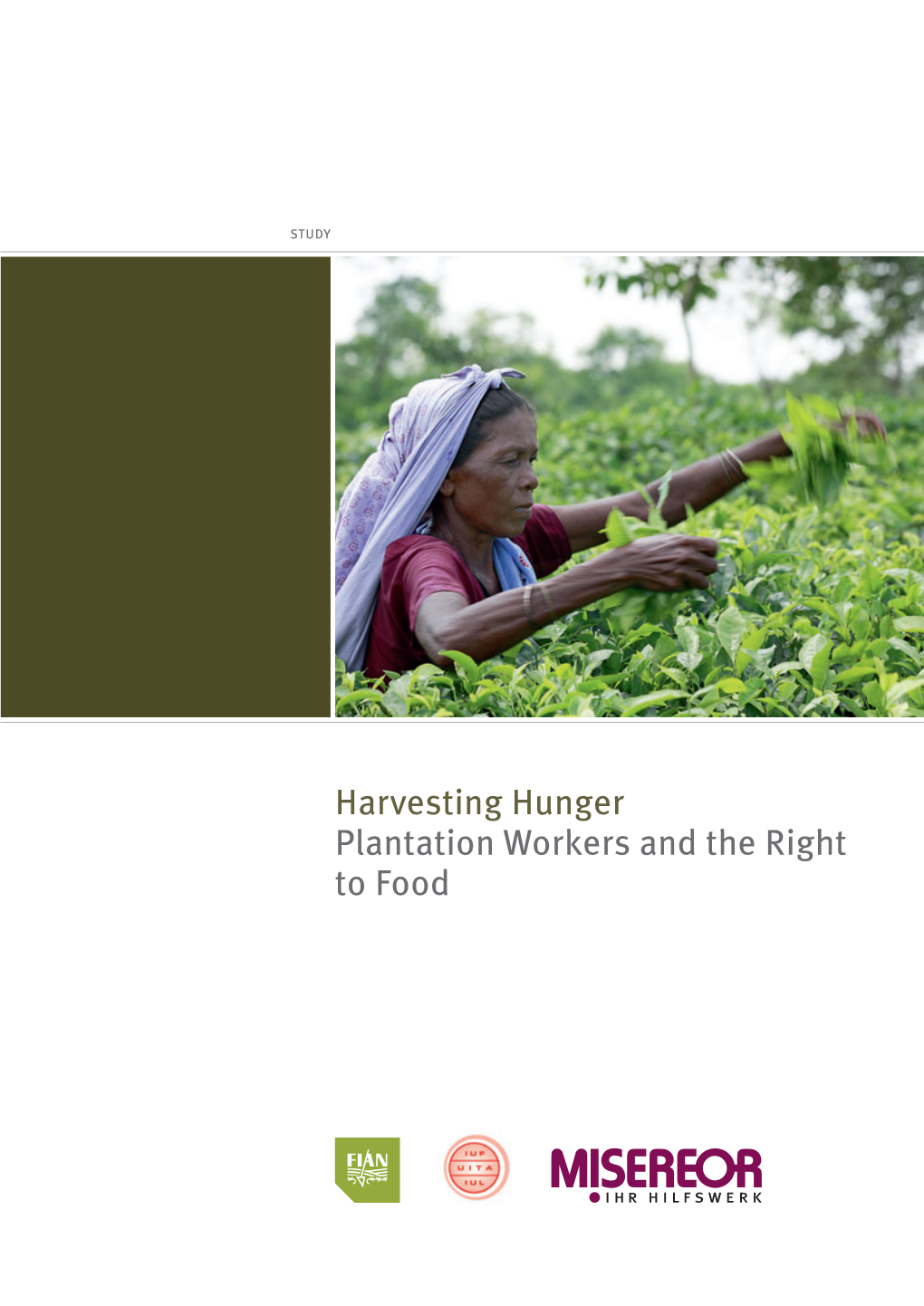

Harvesting Hunger Plantation Workers and the Right to Food Harvesting Hunger Plantation Workers and the Right to Food

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Capacity Needs Assessment of the Tea Value Chain in Kenya

Transforming Agribusiness, Trade and Leadership: A Capacity Needs Assessment of the Tea Value Chain in Kenya Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA) in partnership with African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF) Special Paper No. 17 2017 A Capacity Needs Assessment of the Tea Value Chain in Kenya ISBN 9966 058 69 0 This paper is a result of partnership between the Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis and the African Capacity Building Foundation. We are grateful to all those individuals who particpated in the various stages during the development of this paper. ii Executive summary This report analyses the institutional and human capacities of the tea value chain in Kenya. This is necessitated by the need to initiate transformative actions necessary for enhancing the sub-sector’s productivity and contributions to national economic growth and development. The transformative agenda is also aimed at strengthening agribusiness trade and international competitiveness as envisioned in the Kenya Vision 2030. Tea plays an important role in Kenya’s socio-economic development. Tea is the leading industrial crop in terms of its contribution to the GDP. In 2016, tea accounted for 40 per cent of the marketed agricultural production and contributed 25 percent of total export earnings amounting to USD 1.25 billion (KNBS, 2017). In addition, tea provides livelihoods to approximately over 600,000 smallholders who contribute approximately 60 per cent of total tea production. This notwithstanding, only 14 per cent of tea exported is value added and the remaining is sold in bulk form (GoK, 2016). The low level of value addition results to an estimated loss of USD 12 per kilogram of tea. -

Sustainable Methods of Addressing Challenges Facing Small Holder Tea Sector in Kenya: a Supply Chain Management Approach

Journal of Management and Sustainability; Vol. 2, No. 2; 2012 ISSN 1925-4725 E-ISSN 1925-4733 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Sustainable Methods of Addressing Challenges Facing Small Holder Tea Sector in Kenya: A Supply Chain Management Approach Elias Kiarie Kagira1, Sarah Wambui Kimani2 & Kagwathi Stephen Githii3 1 Department of Business Administration, Africa Nazarene University, Nairobi, Kenya 2 The Catholic University of Eastern Africa, Nairobi, Kenya 3 Department of Business Administration, Africa Nazarene University, Kenya Correspondence: Elias Kiarie Kagira, Department of Business Administration, Africa Nazarene University, PO Box 53067, Nairobi, Kenya. Tel: 254-713-209-606. E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Received: December 21, 2011 Accepted: February 29, 2012 Online Published: May 24, 2012 doi:10.5539/jms.v2n2p75 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jms.v2n2p75 Abstract This Conceptual paper addresses the challenges facing the small holder tea sector in Kenya. It provides background information about tea growing in Kenya, its export performance, and organizational structure. It then categorizes the main challenges into five and provides some solutions to the challenges, borrowing from some supply chain management practices to culminate into competitive strategies. In the face of declining and shifting competitiveness of the small holder tea sector in Kenya, this paper identifies the special role of supplier and customer relationships, value addition, information technology, information sharing, flexibility in internal operations/processes, upgrading of tea seedlings, proper coordination, institutionalization, policy reforms, training, monitoring marketing environment, strategic decisions, irrigation, venturing in new markets through partnership, and civil society involvement as competitive supply chain strategies. -

MITI Magazine – Forests and Energy, Issue 47

ISSUE NO.47|JULY - SEPTEMBER 2020 FORESTS AND ENERGY | THE TREE FARMERS MAGAZINE FOR AFRICA| ENERGY IN WOODY BIOMASS UTILIZING TREE BIOMASS: MATHENGE CROTON NUTS HOME-GROWN (PROSOPIS FOR BIOFUEL, AND LOCALLY JULIFLORA) FOR FERTILIZERS AND OWNED ENERGY CHARCOAL FODDER FORESTS AND ENERGYTHE ACACIAS OF AFRICA BRIQUETTE PRODUCTION IN MAFINGA BGF INITIATES THE CERTIFICATION PROCESS FOR THE INTERNATIONAL TIMBER MARKET I ISSUE 47 | JULY - SEPTEMBER 2020 1 | A PUBLICATION OF BETTER GLOBE FORESTRY | FORESTS AND ENERGY Wonders of Dryland Forestry he Schools’ Green Initiative Challenge is The ten-year project is designed as a competition a unique project implemented by KenGen amongst the participating institutions for the highest TFoundation in partnership with Better Globe seedling survival rates through the application of Forestry and Bamburi Cement Ltd. various innovations at the schools’ woodlots. The main objective is the greening of over 460 Currently, there are 500 schools from the three acres in the semi-arid counties of Embu, Kitui counties taking part in the afforestation contest for and Machakos with Mukau (M. volkensii) and the ultimate prize of educational trips, scholarship Muveshi (S. siamea) tree species as a way of opportunities, and other prizes. Plans are underway mitigating climate change and providing wood to add more schools in the coming years. fuel and alternative income opportunities for the local communities. The afforestation competition is in line with the Government of Kenya’s Vision 2030 to achieve Through the setting up of woodlots in participating 10% forest cover across the country. schools, the project acts as a change agent to establish a tree-planting culture for multiple benefits in dry-land areas. -

TEA Newsletter May 2021 Download

Page 1 Tea Exporters Association Sri Lanka May 2021 SRI LANKA TEA PRODUCTION APRIL 2021/2020 - in MT JANUARY TO APRIL 2021/2020 - in MT (SLTB) SRI LANKA TEA EXPORTS APRIL 2021/2020 - in MT JANUARY TO APRIL 2021/2020 - in MT MAJOR IMPORTERS OF SRI LANKA TEA - JANUARY TO APRIL 2021 - in MT (SL Customs - Courtesy Forbes & Walker Tea Brokers) Page 2 Tea Exporters Association Sri Lanka May 2021 March 2021 World Tea Crop The latest tea crop figures of some leading tea producing countries are furnished below (in million Kg). (Forbes & Walker Tea Brokers) Summary of developments in the major producing countries - May The surge in Covid-19 cases in India and Sri Lanka since April is a major cause of concern for the entire global tea industry. Even though the industries in both countries make their best attempts to continue to function as essential services, they are likely to be hampered by delays along the supply chain in areas of support services, documentation and at customs. At the same time, there are reports of buyers pushing for shipments to be advanced owing to the prevailing situation. An export from China during the first quarter is almost in line with the quantity exported in the first quarter of 2019. Though shipments to Morocco to-date are unusually lower, increased exports to a range of West African destinations have boosted overall exports. Total cumulative crop in India reflects a 9% decline compared with the corresponding period in 2019. Even though Assam has experienced heavy rains in recent weeks, reports indicate that average rainfall in the region up to April is approximately 40% less than last year. -

Sustainable Tea Production in Kenya: Impact Assessment of Rainforest Alliance and Farmer Field School Training Waarts, Y., L

Sustainable tea production in Kenya Impact assessment of Rainforest Alliance and Farmer Field School training Sustainable tea production in Kenya Impact assessment of Rainforest Alliance and Farmer Field School training Yuca Waarts Lan Ge Giel Ton Don Jansen Plant Research International, part of Wageningen UR LEI report 2012-043 June 2012 Project code 2273000285 LEI Wageningen UR, The Hague Sustainable tea production in Kenya: Impact assessment of Rainforest Alliance and Farmer Field School training Waarts, Y., L. Ge, G. Ton and D. Jansen LEI report 2012-043 ISBN/EAN: 978-90-8615-589-7 Price € 29,95 (including 6% VAT) 143 p., fig., tab., app. 3 This study was commissioned by the Netherlands Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation through the Royal Netherlands Embassy in Nairobi, Kenya under contract number NAI-04-03-01. The project title is: The Scalability of Sustainable Tea Value Chain in Kenya. The project is part of the implementation of the LNV-DGIS policy document 'Agriculture, Rural entrepreneurship and Food Security'. Photo cover: Mr. Davies Onduru, ETC East Africa Orders +31 70 3358330 [email protected] This publication is available at www.lei.wur.nl/uk © LEI, part of Stichting Landbouwkundig Onderzoek (DLO foundation), 2012 Reproduction of contents, either whole or in part, is permitted with due reference to the source. 4 LEI is ISO 9001:2008 certified. Contents List of acronyms 8 Preface 9 Summary 11 S.1 Key findings 11 S.2 Methodology 13 1 Introduction 15 1.1 Aim of KTDA 15 1.2 Aim of Rainforest Alliance -

Sustainable Sourcing : Markets for Certified Chinese

SUSTAINABLE SOURCING: MARKETS FOR CERTIFIED CHINESE MEDICINAL AND AROMATIC PLANTS In collaboration with SUSTAINABLE SOURCING: MARKETS FOR CERTIFIED CHINESE MEDICINAL AND AROMATIC PLANTS SUSTAINABLE SOURCING: MARKETS FOR CERTIFIED CHINESE MEDICINAL AND AROMATIC PLANTS Abstract for trade information services ID=43163 2016 SITC-292.4 SUS International Trade Centre (ITC) Sustainable Sourcing: Markets for Certified Chinese Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Geneva: ITC, 2016. xvi, 141 pages (Technical paper) Doc. No. SC-2016-5.E This study on the market potential of sustainably wild-collected botanical ingredients originating from the People’s Republic of China with fair and organic certifications provides an overview of current export trade in both wild-collected and cultivated botanical, algal and fungal ingredients from China, market segments such as the fair trade and organic sectors, and the market trends for certified ingredients. It also investigates which international standards would be the most appropriate and applicable to the special case of China in consideration of its biodiversity conservation efforts in traditional wild collection communities and regions, and includes bibliographical references (pp. 139–140). Descriptors: Medicinal Plants, Spices, Certification, Organic Products, Fair Trade, China, Market Research English For further information on this technical paper, contact Mr. Alexander Kasterine ([email protected]) The International Trade Centre (ITC) is the joint agency of the World Trade Organization and the United Nations. ITC, Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland (www.intracen.org) Suggested citation: International Trade Centre (2016). Sustainable Sourcing: Markets for Certified Chinese Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, International Trade Centre, Geneva, Switzerland. This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. -

Making Kenya's Efficient Tea Markets More Inclusive

Kenya MAFAP POLICY BRIEF #5 June 2013 Monitoring African Food and Agricultural Policies Making Kenya’s efficient tea markets more inclusive Main Findings and Recommendations Kenyan smallholder tea farmers generally received prices closer to those in international markets. This reflects the country’s liberalized market structure for tea and the lack of distortions resulting from domestic policies. The close alignment between domestic and international prices may also be due to the efficient organization of smallholders who process and market their tea under the Kenya Tea Development Agency Ltd. (KTDA). However, MAFAP analysis shows that tea prices were vulnerable to short-term shocks due to Kenya’s reliance on only a few key trade partners. MAFAP analysis suggests that, although the tea market is already very efficient, it may be further improved by: ► encouraging the entry of new buyers at the Mombasa Tea Auction; ► reducing exposure to shocks by diversifying export markets; and ► encouraging domestic value addition, processing and labelling. An analysis of incentives received by smallholder farmers who are shareholders of the KTDA compared to those who are not, could also be useful. SUMMARY not fully reflect this quality. This may be due to the high concentration of market power among a few multinational Tea is Kenya’s main export, and the tea industry is one of companies that have a great deal of control over local the country’s largest private sector employers. Over 60 production, processing and pricing. percent of Kenyan tea is produced by smallholder farmers and marketed through the KTDA. MAFAP analysis shows that Smallholder tea farmers are not a homogenous group, and KTDA smallholders receive prices close to world market prices there may be differences in the level of incentives they receive. -

Sustainability of Smallholder Tea Production in Developing Countries: Learning Experiences from Farmer Field Schools in Kenya

International Journal of Development and Sustainability Online ISSN: 2186-8662 – www.isdsnet.com/ijds Volume 1 Number 3 (2012): Pages 714-742 ISDS Article ID: IJDS12091107 Special Issue: Development and Sustainability in Africa – Part 1 Sustainability of smallholder tea production in developing countries: Learning experiences from farmer field schools in Kenya D.D. Onduru 1*, A. De Jager 2, S. Hiller 3, R. Van den Bosch 4 1 ETC-East Africa, P.O. Box 76378-00508 Yaya, Nairobi, Kenya 2 International Fertiliser Development Centre (IFDC), North and West Africa Division, PMB CT 284, Cantonments, Accra, Ghana 3 Wageningen University and Research Centre-LEI, P.O. Box 29703, 2502LS The Hague, The Netherlands 4 Wageningen University and Research Centre-Alterra, P.O. Box 29703, 2502LS The Hague, The Netherlands Abstract A study to determine the impacts of farmers field schools (FFS) on smallholders’ adoption of good agricultural practices in tea and to assess sustainability of smallholder tea production was conducted in the highlands of Kenya. Input-output data on tea management and on sustainability indicators (score 0-10) were collected from a sample of 120 FFS participants at the beginning of the study and from 60 randomly selected FFS participants and a comparison group of 60 non-FFS participants at the end of the study, 18 months later. The study showed that the smallholder tea systems are moving towards social sustainability and economic returns were positive. Sustainability indicator scores, for FFS members, increased by 4% from the base period. The FFS participants also attained a significantly higher level of farm sustainability, knowledge gains on good agricultural practices (GAP) and higher yields and farm and tea income than their non-FFS counterparts. -

Tea Sector Report

TEA SECTOR REPORT Common borders. Common solutions. 1 DISCLAIMER The document has been produced with the assistance of the European Union under Joint Operational Programme Black Sea Basin 2014-2020. Its content is the sole responsibility of Authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. Common borders. Common solutions. 2 Contents 1. Executıve Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Tea Sector Report ............................................................................................................................................ 7 1.1. Current Status ............................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.1. World .................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.2. Black Sea Basin ................................................................................................................................... 49 1.1.3. National and Regional ........................................................................................................................ 60 1.2. Traditional Tea Agriculture and Management ............................................................................................ 80 1.2.1. Current Status ................................................................................................................................... -

Productivity and Resource Use in Ageing Tea Plantations

Productivity and resource use in ageing tea plantations Promotoren: Prof. dr. ir. J.H.J. Spiertz Emeritus hoogleraar Gewasecologie, met bijzondere aandacht voor nutriënten- en stofstromen Prof. dr. ir. O. Oenema Hoogleraar Nutriëntenmanagement en bodemvruchtbaarheid Co-promotor: Prof. Dr. P.O. Owuor Professor of Chemistry, Maseno University, Kenya Promotiecommisie: Prof. dr. K.E. Giller Wageningen Universiteit Prof. dr. G. Hofman Universiteit Gent, België Prof. dr. ir. E.M.A. Smaling ITC, Enschede Dr. ir. H.A.M. van der Vossen Consultant Internationale Samenwerking Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de C.T. de Wit onderzoekschool: Production Ecology and Resource Conservation. Productivity and resource use in ageing tea plantations David M. Kamau Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 28 januari 2008 des namiddags te half twee in de Aula D.M. Kamau (2008) Productivity and resource use in ageing tea plantations Kamau, D.M. – [S.l.: s.n.]. Ill. PhD thesis Wageningen University. – With ref. – With summaries in English, Dutch and Kiswahili. ISBN: 978-90-8504-808-4 Abstract Kamau, D.M., 2008. Productivity and resource use in ageing tea plantations. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands. With summaries in English, Dutch and Kiswahili, 140 pp. The tea industry in Kenya is rural-based and provides livelihood to over three million people along the value chain. The industry which started in the first quarter of the 20th century has continued to increase in terms of production and total acreage. -

Nar Suyu Ve Yeşil Çay İlaveli Kalorisi Azaltılmış Fonksiyonel Geleneksel Karışık Meyve Marmelatı Üretimi

Akademik Gıda® ISSN Online: 2148-015X http://dergipark.gov.tr/akademik-gida Akademik Gıda 18(2) (2020) 143-155, DOI: 10.24323/akademik-gida.758817 Araştırma Makalesi / Research Paper Nar Suyu ve Yeşil Çay İlaveli Kalorisi Azaltılmış Fonksiyonel Geleneksel Karışık Meyve Marmelatı Üretimi Büşra Acoğlu1 , Perihan Yolcı Ömeroğlu1,2 1Bursa Uludağ Üniversitesi, Ziraat Fakültesi, Gıda Mühendisliği Bölümü, Bursa 2Bursa Uludağ Üniversitesi, Bilim ve Teknoloji Uygulama ve Araştırma Merkezi, Bursa Geliş Tarihi (Received): 10.05.2020, Kabul Tarihi (Accepted): 13.06.2020 Yazışmalardan Sorumlu Yazar (Corresponding author): [email protected] (P. Yolcı Ömeroğlu) 0 224 294 14 01 0 224 294 14 02 ÖZ Bu çalışmada, kalorisi azaltılmış karışık meyve (%22 armut, %16 elma, %16 ayva, %12 kivi, %12 çilek, %8 havuç, %8 siyah havuç, %4 yaban mersini ve %2 portakal kabuğu) marmelatının üretilme olanağının araştırılması, yeni fonksiyonel bir ürünün geliştirilmesi ve gelecekte bu konuda yapılacak çalışmalara baz teşkil edilmesi amaçlanmıştır. Geliştirilen ürünlerin fonksiyonelliğini artırmak için su yerine nar suyu ve yeşil çay infüzyonu kullanılmıştır. Ürünlerin kalorisini azaltmak için, şeker miktarının azaltılması hedeflenmiş ve kullanılan meyvelerin miktarlarının tüketiciye tatlılık hissi verecek oranlarda optimize edilmesi sağlanmıştır (Düşük şekerli form). Ayrıca, şeker yerine bal ve ticari stevia şekeri kullanılarak iki ayrı form daha geliştirilmiştir. Geliştirilen marmelatların bazı fizikokimyasal özellikleri, toplam antioksidan kapasitesi ve toplam fenolik madde içerikleri ve duyusal özellikleri incelenmiştir. Ticari stevia şekeri ile tatlandırılmış marmelatın diğer marmelatlar arasında en yüksek toplam fenolik madde miktarı (876.34 mg gallik asit eşdeğeri /100 g (kuru madde: KM), CUPRAC (602.45 mg trolox eşdeğeri (TE)/100 g KM), DPPH (88.65 mg TE/100 g KM) ve FRAP (435.38 mg TE/100 g KM) değerine sahip olduğu tespit edilmiştir. -

Harvesting Hunger Plantation Workers and the Right to Food Harvesting Hunger Plantation Workers and the Right to Food

STUDY Harvesting Hunger Plantation Workers and the Right to Food Harvesting Hunger Plantation Workers and the Right to Food Content Content . 2 Imprint . 2 Foreword . 3 Executive Summary . 4 1. How plantation workers are ignored in food security debates . 6 1.1 Plantation workers in the global food system . 6 1.2 Invisible and ignored . 8 2. The right to food and worker’s rights violations – an overview . 9 2.1 Wages and the right to food . 10 2.2 Discrimination and the right to food . 11 2.3 Working conditions, social protection and the right to food . 12 2.4 The right to organise, criminalization and the right to food . 13 3. The Case of tea plantation workers . 15 3.1 The global tea sector . 15 3.2 Wages and working conditions on tea plantations . 16 3.3 Starvation and dying from hunger. 19 3.4 Laws and voluntary codes – failing to ensure the right to food and worker’s rights . 21 4. Conclusion and recommendations . 24 4.1 The need for a human rights based agenda . 24 4.2 Recommendations . 24 4.2.1 States measures to respect, protect and fulfi l plantation workers right to food . 24 4.2.2 The right to food of plantation workers on the international agenda . 25 4.2.3 A framework for transnational food companies to meet their responsibilities . 26 Literature . 26 Imprint Published by: FIAN International Bischöfl iches Hilfswerk MISEREOR e.V. Willy-Brandt-Platz 5 Mozartstraße 9 69115 Heidelberg – Germany 52064 Aachen Phone: + 49 6221 65300-30 Germany www.fi an.org Phone: +49 (0)241 442 0 Contact: Cordova@fi an.org www.misereor.org Authors: Contact: Roman Herre Bischöfl iches Hilfswerk MISEREOR e.V.