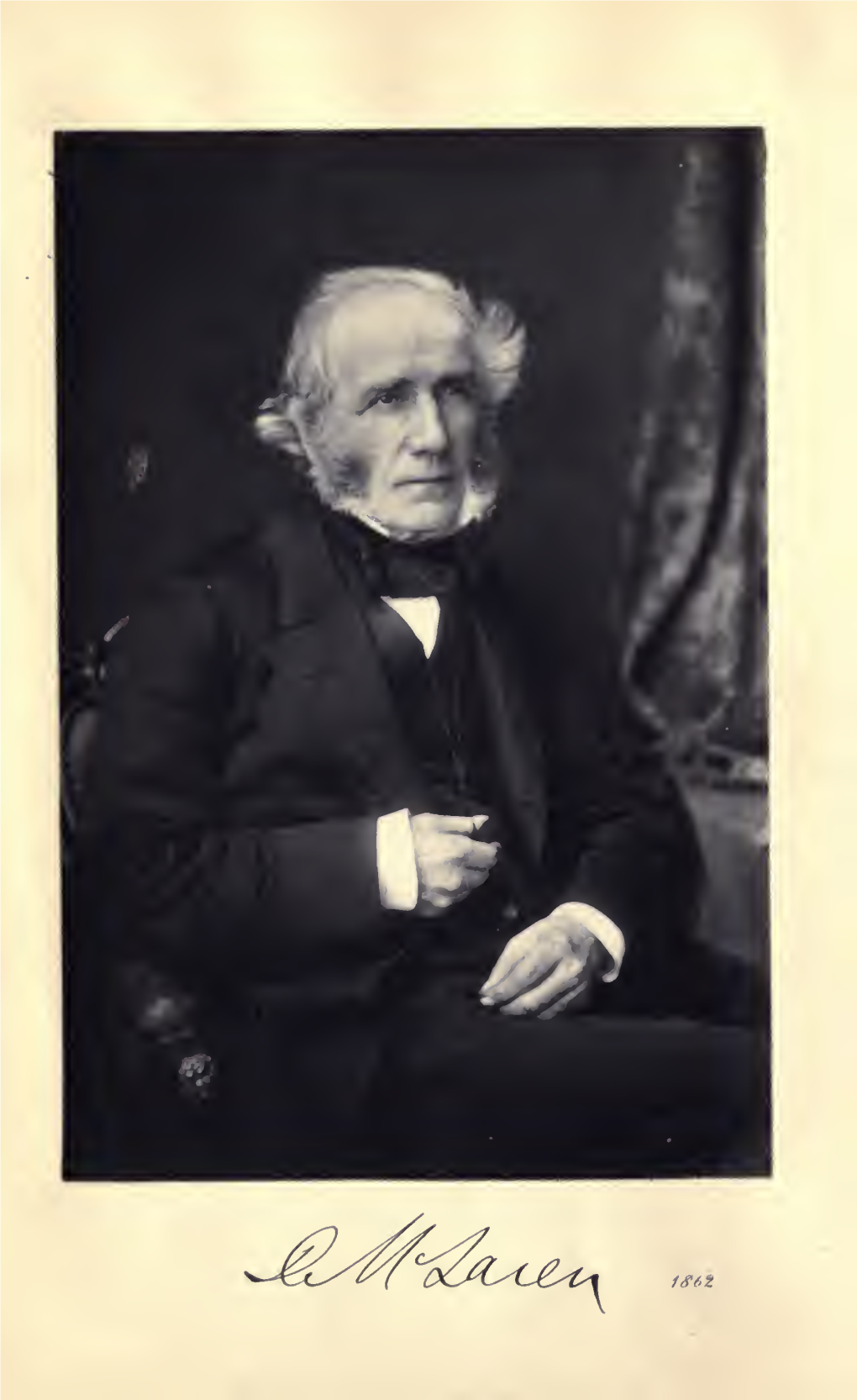

The Life and Work of Duncan Mclaren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

David Steuart Erskine, 11Th Earl of Buchan: Founder of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

Society of Antiquaries of Scotland The Scottish Antiquarian Tradition: Essays to mark the bicentenary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1780-1980 Edited by A S Bell ISBN: 0 85976 080 4 (pbk) • ISBN: 978-1-908332-15-8 (PDF) Except where otherwise noted, this work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work and to adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: A Bell, A S (ed) 1981 The Scottish Antiquarian Tradition: Essays to mark the bicentenary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1780-1980. Edinburgh: John Donald. Available online via the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland: https://doi.org/10.9750/9781908332158 Please note: The illustrations listed on p ix are not covered by the terms of the Creative Commons license and must not be reproduced without permission from the listed copyright holders. The Society gratefully acknowledges the permission of John Donald (Birlinn) for al- lowing the Open Access publication of this volume, as well as the contributors and contributors’ estates for allowing individual chapters to be reproduced. The Society would also like to thank the National Galleries of Scotland and the Trustees of the National Museum of Scotland for permission to reproduce copyright material. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders for all third-party material reproduced in this volume. -

The Liberal Party in Scotland, 1843- 1868: Electoral Politics and Party Development

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Liberal party in Scotland, 1843- 1868: electoral politics and party development Gordon F. Millar Departments of Scottish and Modern History University of Glasgow Presented for the degree of Ph.D. at the University of Glasgow © Gordon F. Millar October 1994 ProQuest Number: 10992153 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10992153 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Edinburgh Politics: 1832-1852

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. EDINBURGH POLITICS: 1832-1852 by Jeffrey Charles Williams Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh June 1972 Contents Preface Abbreviations One Social and Religious Groups in Early Victorian Edinburgh Two Political Groups in Early Victorian Edinburgh Three Whiggery Triumphant: 1832-1835 Four The Growth of Sectarian Politics: 1835-1841 Five The Downfall of the Whigs: 1841-184 7 Six The Breakdown of the Liberal Alliance: 184 7-1852 Seven Conclusion A!;)pendices 1. A Statistical Comparison of the Edinburgh Electorates of 183 5 and 1866 11. Electioneering in Edinburgh, 1832-1852 111. An Occupational Analysis of Town Councillors IV. An Occupational Analysis of the Edinburgh 'Radical Vote' of 1834 Bibliography ********* (i) Preface The Scottish Reform A~t of 1832 and the Scottish Municipal Reform Act of 1833 destroyed the domination of the Tory party over Edinburgh politics. -

People and Buildings

Augustine United Church: The Church on the Bridge People and buildings Part 2 Our story in people and buildings Augustine United Church: The Church on the Bridge People and buildings Social and Geographical Context A new beginning To take a point in history: Friday 8 November 1861. Queen Victoria had reigned over Britain and her burgeoning empire for 24 years. Across the Atlantic, the American Civil War, begun earlier in the year, was building momentum. In Edinburgh, Augustine Church on George IV Bridge, some five years in the creation, was at last opened. Present at the opening service was, amongst many other eminent citizens of the city, the publisher Adam Black, a former Lord Provost of Edinburgh, and currently it’s MP. He was there not just as a city dignitary but as an influential member of Edinburgh’s pre-eminent non-conformist church congregation. The minister at this time, the Revd William Lindsay Alexander, was himself a noted Edinburgh citizen – a scholar, ecclesiastical innovator, and influential preacher of the day. Given his position and popularity, it is probably not without significance that instead of taking to the pulpit himself that day, the invited preacher was the Revd Thomas Guthrie, the eminent minister of nearby St John's Free Church (now St Columba's Free Church, Johnston Terrace) but known as a social reformer and founder of ‘Ragged Schools’ in the city. Photo: Statue of Thomas Guthrie in Princes Street Gardens, Edinburgh The inscription on the statue of Guthrie in Princes Street Gardens reads: ‘A friend of the -

The Life and Work of Duncan Mclaren

CHAPTER XXI. FRANCHISE REFORM. 1833 PAKLIAMENTARY reform was the first public question which engaged Mr. M cLaren's attention at the threshold of his Politi cai v. eccle- siastical career. At the beginning of the present centuryJ it en- ,,..,, franchise grossed the public mind. To earnest-minded young men, c more particularly among the class with whom Mr. M Laren was associated, it represented the cause of human freedom. It spoke of the rights of man rights withheld, but which must be asserted if patriotism were to be preserved and faith vindicated and maintained for it religious ; appealed not only to the love of freedom innate in the Scottish character, but likewise to the sense of responsibility to God. It was an outcome of the Reformation a develop- ment of the Protestantism which had established in Scot- land a democratic, self-governing Church. It was a poli- tical manifestation of the Scottish Presbyterianism, which in its purer and intenser aspects had secured the ecclesias- tical franchise for the members of Christ's Church, without respect of social status or of sex. c To this early adopted faith Mr. M Laren proved true to the end of his life. He laboured to secure the parliamentary franchise for every member of the common- wealth for every man and woman householder, as a right as well as a trust, just as the ecclesiastical franchise was 140 Life of Duncan McLaren. regarded as part and parcel of the membership of his church. In his private memoranda, written in the spring of 1886, he thus described his introduction to political work : " I had never been an active working politician up to 1833. -

Inventory Acc.5000 (Incorporating Acc.7873 and Dep.312

Inventory Acc.5000 (Incorporating Acc.7873 and Dep.312) = = = = = = = = = = = = = = National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland CONTENTS I. BUSINESS RECORDS a) Editorial, (1-16). b) Production, (17-41). c) Administration, (42-73). d) Buildings and Property, (74-75). e) Historical Records, (76-79). II. AUTHORS a) Agreements/Assignations, (80-81). b) Agencies, (82-95). c) Reports/Royalties, (96-139). III. LETTER BOOKS a) Nineteenth Century, (140-144). b) Twentieth Century, (145-187). IV. 19th CORRESPONDENCE (see separate list) a) Special, (188). b) Literary/Business, (189-219). V. 20th CORRESPONDENCE Roneo System (220-1108), (index in slip folders). VI. MISCELLANEOUS (1109-1119). VII. DARIEN PRESS (1120-1127). VIII. LONGMANS (BUSINESS RECORDS) a) Administration, (1128-1170). b) Production, (1171-1207). c) Editorial, (1208-1239). d) Authors i Royalties, (1240-69) ii Book Files, (1270-1387). IX. ADDITIONAL MATERIAL (OLIVER & BOYD) (1388-1424) Trade Catalogues/Educational Works, etc. X. ADDITIONAL MATERIAL (OLIVER & BOYD) (1425) Miscellaneous I. BUSINESS RECORDS a) Editorial 1. Copyright Ledger No.1, (1818-26). 2. Copyright Ledger No.2, (1824-37). 3. Copyright Ledger No.3, (1838-57). 4. Copyright Ledger No.4, (1847-96). 5. Copyright Ledger No.5, (1862-98). 6. Copyright Ledger No.6, (1897-1914). 7. Copyright Ledger No.7, (1912-26). 8. Copyright Ledger No.8, (School Books), (1926-50). 9. Copyright Ledger No.9, (General), (1926-50). 10. Copyright Ledger No.10, (School Books), (1935-56). 11. Copyright Ledger (Gurney & Jackson), 1921-46). -

Sir James Young Simpson

Sir James Young Simpson Reference and contact details: GB 779 RCSEd JYS 1-1884 Location: RS R1; RS R2; Plans chest Title: James Young Simpson Collection Dates of Creation: 1823-1948 Held at: The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh Extent: 1884 items as at 2012. Further material in the RCSEd Museum Name of Creator: Simpson, J Y; Fergusson W; etc Language of Material: English. Some French; some Latin Level of Description: item; file Date(s) of Description: 1981; revised 2009; 2012 Biographical History/Provenance: James Simpson (1811-1870) (pictured centre) was born in Bathgate, West Lothian, seventh son of a baker. He was educated at the local school and went to Edinburgh University at the age of 14. Too young to graduate, he became a Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1830 before graduating in 1832. He became Professor of Midwifery at Edinburgh University in 1840, Physician to Queen Victoria in 1847, President of the Royal College of Physicians in 1850 and Baronet in 1866. A man of enormous energy and great personal charm, Simpson was a keen controversialist and much loved physician. His contributions to obstetrics are overshadowed by his discovery of the anaesthetic effects of chloroform in November 1847. After ether was discovered in 1846, Simpson was quick to use it to relieve the pains of labour, earning the gratitude of countless women and the condemnation of some members of the church and the medical profession. Simpson was a doughty advocate of the cause of general anaesthesia and his final vindication came when Queen Victoria had chloroform at the birth of Prince Leopold in 1853. -

Adam Black Travel Insurance Guide

Adam Black Card Insurance Guide 234027815.indd 1 28/04/2021 18:40 234027815.indd 2 28/04/2021 18:40 Insurance Guide This booklet explains the travel and other insurance benefits available with your Adam Black Card. In addition, it details the emergency medical cover available to Adam Black cardholders. Information contained in this Insurance Guide is correct at March 2021, but is subject to change as specified in this booklet. From time to time it may be necessary to alter the terms of this Insurance Guide. When changes occur, we will let you know. Any such alteration will only apply to trips booked after we have notified them, or at a specific future date. This Travel Insurance Policy Document contains full terms and conditions of the insurance; you should check them carefully to ensure that the cover provided meets your needs and you should review it periodically and before booking any trip to ensure it remains adequate. It is important to keep the insurer informed of any changes which might affect your cover, especially changes in health which affect beneficiaries, their immediate family or other travellers. This Insurance Guide contains details of the various insurance policies available with your Adam Black Card. Each policy is provided by a different insurance provider, details of which can be found in the corresponding insurance policy. Please be aware that, although the different insurance policies contain the same or similar terminology, each policy should be read on its own as the meaning of such terminology may differ with every policy. For example, in the insurance policies, each insurer refers to themselves as we, us or the insurer and in some circumstances The Company. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Charlotte Forten: Coming of Age as a Radical Teenage Abolitionist, 1854-1856 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9ss7c7pk Author Glasgow, Kristen Hillaire Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Charlotte Forten: Coming of Age as a Radical Teenage Abolitionist, 1854-1856 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Kristen Hillaire Glasgow 2019 © Copyright by Kristen Hillaire Glasgow 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Charlotte Forten: Coming of Age as a Radical Teenage Abolitionist, 1854-1856 by Kristen Hillaire Glasgow Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Brenda Stevenson, Chair In 1854, Charlotte Forten, a free teenager of color from Philadelphia, was sent by her family to Salem, Massachusetts. She was fifteen years old. Charlotte was relocated to obtain an education worthy of the teenager’s socio-elite background. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law had a tremendous impact on her family in the City of Brotherly Love. Even though they were well-known and affluent citizens and abolitionists, the law’s passage took a heavy toll on all people of color in the North including rising racial tensions, mob attacks, and the acute possibility of kidnap. Charlotte Forten: Coming of Age as a Radical Teenage Abolitionist is an intellectual biography that spans her teenage years from 1854-1856. Scholarship has maintained that Charlotte was sent to Salem solely as a result of few educational opportunities in Philadelphia. -

Reconsidering the Highland Roots of Adam Ferguson

‘A Bastard Gaelic Man’: Reconsidering the Highland Roots of Adam Ferguson Denise Ann Testa College of Arts University of Western Sydney Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Humanities and Languages September 2007 Supervisor: Dr David Burchell © Denise Testa 2007 DEDICATION In memory of Anna Sutherland Acknowledgements A postgraduate student cannot successfully complete their task without the aid of numerous people. Dr David Burchell, my supervisor has been unwavering in his support and generosity. His patience has been exceptional. I also must commend the University of Western Sydney for the patience and support I received within the institution. Three months of research in Edinburgh and London, would not have been possible without the generous financial support of the Centre for Cultural Research at UWS and a grant from the Australian Bicentennial Scholarship Committee. The staff of the University of Western Sydney’s branch libraries supplied the all too numerous document delivery requests I placed. A special thank-you must go to Judy Egan, Cheryl Harris and the staff of Blacktown and Ward libraries. Thanks must also go to the staff of Fisher Library at the University of Sydney, the National Library of Australia, the National Archives of Scotland, the National Library of Scotland and the British Library. The staff at the Special or Rare books Collections at Fisher Library, the University of Canberra, the University of Edinburgh and the University of Stirling also came to my aid. A special thank-you must go to Associate Professor Brian Taylor for his encouragement over the years and also the help of his son, Alasdair Taylor, who supplied moral support and introduced me to some contacts in Edinburgh. -

This Post Is a Free, Self-Guided Tour of Edinburgh, Along with a Map and Route, Put Together by Local Tour Guides for Free Tours by Foot

This post is a free, self-guided tour of Edinburgh, along with a map and route, put together by local tour guides for Free Tours by Foot. You can expect to walk nearly 2 miles or just over 3.2 kilometres. Below is the abridged version. You can get the full version with directions by downloading this map, clicking on this PDF, or downloading our audio tour. Additionally, you can also take free guided walking tours. These tours are in reality pay-what-you-wish tours. Click the map to enlarge or to download it to your smartphone. Edinburgh is one of the most historic cities in Scotland and the entire United Kingdom. In addition to its medieval history, this city’s history of education and learning has also affected our modern lives. Whether it be the contributions that Adam Smith made to our modern understanding of a free market economy or the inspiration pulled from Edinburgh for the Harry Potter series, the people and the atmosphere of this city have contributed to the world in many important ways. This tour will lead you through some of the most influential and popular landmarks in Edinburgh with plenty of sightseeing on the way. In addition to historic sites, I’ll also point out some options for food, museums, art, and other ways to make the most of your time in Edinburgh. This tour will begin at Edinburgh Castle and continue downhill, mostly following the Royal Mile, with a few turns onto other streets. Once you’ve made your way to the castle gates, you’ll be ready to begin this tour.