People and Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

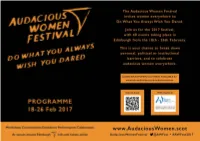

2017 Programme

Saturday 18th February Saturday 18th February Unleash your Audacious Power Unleash your Audacious Power 13:30–15:50: City Art Centre 13:30–15:50: City Art Centre 2 Market St, Edinburgh EH1 1DE 2 Market St, Edinburgh EH1 1DE Free but booking essential Free but booking essential This creative workshop led by Anna Czekala is designed to expand self-aware- This creative workshop led by Anna Czekala is designed to ness and unleash our audacious powers. We will explore our audacious dreams expand self-awareness and unleash our audacious powers. and desires, challenging self-limiting beliefs and destructive thinking patterns. We will explore our audacious dreams and desires, challenging self-limiting beliefs and destructive thinking patterns. EXHIBITIONS Saturday 18th February Pioneering Females: 1st Feb to 28th Feb Mexican Mosaics Workshop Monday- Wed 10am - 8pm, Thurs - Sat 10am - 5pm 10.00-15.30: Lauriston Castle, EH4 6AD Edinburgh Central Library, George IV Bridge, EH1 1EG Tickets £30 plus £2.45 booking fee. Free Ever wanted to try a completely new craft and make a A crowd-sourced exhibition of Audacious Women in the last beautiful mosaic? In this beginners workshop you will 100 years, drawn from the archives of www.scran.ac.uk, make a small mosaic panel using genuine glass mosaic highlighting pioneering women in many different fields from tiles and pieces of fractured glass and mirror. It will be politics to science. You are also invited to permanently add taught by Margaret Findlay in the beautiful surroundings the audacious women in your own life to Scotland’s digital of the historic Lauriston Castle. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Building Stones of Edinburgh's South Side

The route Building Stones of Edinburgh’s South Side This tour takes the form of a circular walk from George Square northwards along George IV Bridge to the High Street of the Old Town, returning by South Bridge and Building Stones Chambers Street and Nicolson Street. Most of the itinerary High Court 32 lies within the Edinburgh World Heritage Site. 25 33 26 31 of Edinburgh’s 27 28 The recommended route along pavements is shown in red 29 24 30 34 on the diagram overleaf. Edinburgh traffic can be very busy, 21 so TAKE CARE; cross where possible at traffic light controlled 22 South Side 23 crossings. Public toilets are located in Nicolson Square 20 19 near start and end of walk. The walk begins at NE corner of Crown Office George Square (Route Map locality 1). 18 17 16 35 14 36 Further Reading 13 15 McMillan, A A, Gillanders, R J and Fairhurst, J A. 1999 National Museum of Scotland Building Stones of Edinburgh. 2nd Edition. Edinburgh Geological Society. 12 11 Lothian & Borders GeoConservation leaflets including Telfer Wall Calton Hill, and Craigleith Quarry (http://www. 9 8 Central 7 Finish Mosque edinburghgeolsoc.org/r_download.html) 10 38 37 Quartermile, formerly 6 CHAP the Royal Infirmary of Acknowledgements. 1 EL Edinburgh S T Text: Andrew McMillan and Richard Gillanders with Start . 5 contributions from David McAdam and Alex Stark. 4 2 3 LACE CLEUCH P Map adapted with permission from The Buildings of BUC Scotland: Edinburgh (Pevsner Architectural Guides, Yale University Press), by J. Gifford, C. McWilliam and D. -

The Cockburn Association Edinburgh and East Lothian

THE COCKBURN ASSOCIATION EDINBURGH AND EAST LOTHIAN DOORSDAYS OPEN SAT 29 & SUN 30 SEPTEMBER 2018 Cover image: Barnton Quarry ROTOR Bunker. EDINBURGH DOORS OPEN DAY 2018 SAT 29 & SUN 30 SEPTEMBER SUPPORT THE COCKBURN ASSOCIATION AND EDINBURGH DOORS OPEN DAY Your support enables us to organise city WHO ARE WE? wide free events such as Doors Open Day, The Cockburn Association (The Edinburgh bringing together Edinburgh’s communities Civic Trust) is an independent charity which in a celebration of our unique heritage. relies on the support of its members to protect All members of the Association receive and enhance the amenity of Edinburgh. We an advance copy of the Doors Open Day have been working since 1875 to improve programme and invitations throughout the built and natural environment of the city the year to lectures, talks and events. – for residents, visitors and workers alike. If you enjoy Doors Open Days please We campaign to prevent inappropriate consider making a donation to support our development in the City and to preserve project www.cockburnassociation.org.uk/ the Green Belt, to promote sustainable donate development, restoration and high quality modern architecture. We are always happy If you are interested in joining the Association, visit us online at www.cockburnassociation. to advise our members on issues relating org.uk or feel free to call or drop in to our to planning. offices at Trunk’s Close. THE COCKBURN ASSOCIATION The Cockburn Association (The Edinburgh Civic Trust) For Everyone Who Loves Edinburgh is a registered Scottish charity, No: SC011544 TALKS & TOURS 2018 P3 ADMISSION BALERNO P10 TO BUILDINGS BLACKFORD P10 Admission to all buildings is FREE. -

Churches & Places of Worship in Scotland Aberdeen Unitarian Church

Churches & Places of Worship in Scotland Aberdeen Unitarian Church - t. 01224 644597 43a Skene Terrace, Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire, AB10 1RN, Scotland Aberfoyle Church of Scotland - t. 01877 382391 Lochard Road, Aberfoyle near Stirling, Stirlingshire, FK8 3SZ, Scotland All Saints Episcopal Church - t. 01334 473193 North Castle Street, St Andrews, Fife, KY16 9AQ, Scotland Allan Park South Church - t. 01786 471998 Dumbarton Road, Stirling, Stirlingshire, FK8 2LQ, Scotland Almond Vineyard Church - t. 0131 476 6640 Craigs Road, Edinburgh, Midlothian, EH12 8NH, Scotland Alyth Parish Church - t. 01828 632104 Bamff Road, Alyth near Blairgowrie, Perthshire, PH11 8DS, Scotland Anstruther Parish Church School Green, Anstruther, Fife, KY10 3HF, Scotland Archdiocese of Glasgow - t. 0141 226 5898 196 Clyde Street, Glasgow, Lanarkshire, G1 4JY, Scotland Augustine United Church - t. 0131 220 1677 41 George IV Bridge, Edinburgh, Midlothian, EH1 1EL, Scotland Bible Baptist Church - t. 01738 451313 4 Weir Place, Perth, Perthshire, PH1 3GP, Scotland Broom Church - t. 0141 639 3528 Mearns Road, Newton Mearns, Renfrewshire, G77 5EX, Scotland Broxburn Baptist Church - t. 01506 209921 Freeland Avenue, Broxburn, West Lothian, EH52 6EG, Scotland Broxburn Catholic Church - t. 01506 852040 34 West Main Street, Broxburn, West Lothian, EH52 5RJ, Scotland The Bruce Memorial Church - t. 01786 450579 St Ninians Road, Cambusbarron near Stirling, Stirlingshire, FK7 9NU, Scotland Cairns Church of Scotland - t. 0141 956 4868 11 Buchanan Street, Milngavie, Dunbartonshire, G62 8AW, Scotland Calvary Chapel Edinburgh - t. 0131 660 4535 Danderhall Community Centre, Newton Church Road, Danderhall near Dalkeith, Midlothian, EH22 1LU, Scotland Calvary Chapel Stirling - t. 07940 979503 2-4 Bow Street, Stirling, Stirlingshire, FK8 1BS, Scotland Catholic Church of the Sacred Heart - t. -

Edinburgh Notes

The Chapels Society Edinburgh weekend visit notes, 2-4 May 2015 One thing which is soon noticeable when you visit Edinburgh is the profusion and variety of church buildings. There are several factors which help to account for this: The laying out of the ‘New Town’ from the 18th century, north of what is now Princes St, whose population needed to be served by suitable places of worship. Divisions within the Church of Scotland, most notably the Disruption of 1843 which resulted in the formation of the Free Church of Scotland. Revival and revivalism from the late 1850s through to 1905/6, leading to the establishment of evangelical churches and missions from existing churches. The desire of every denomination to establish a presence within Scotland’s capital, often of a suitably imposing and aesthetically satisfying nature (the Catholic Apostolic Church offers a prime example of this). The planting of new congregations in post-war suburban housing areas, although many of these have struggled to establish themselves and closures have already occurred. The arrival of new denominations, some taking over buildings constructed for Presbyterian use. For example, Holy Corner (that’s what you ask for on the bus!), around the junction of Morningside Rd and Colinton Rd, you can see Christ Church (Scottish Episcopal), Baptist (now Elim Pentecostal), United (now Church of Scotland / United Reformed), and the Eric Liddell Centre (formerly Church of Scotland). As a student here in the late 1970s, I remember the buses being busy with people travelling to Sunday morning worship. That may not be so now, but a surprising quantity of church buildings remain in use for worship. -

November 2018 News from Sei and Michaelmas Ordinations and Licensings

NOVEMBER 2018 NEWS FROM SEI AND MICHAELMAS ORDINATIONS AND LICENSINGS Eleanor Charman (left) was ordained Deacon by Bishop Mark on 15 September in St Andrew’s Cathedral Inverness (Moray, Ross and Caithness) to serve as Assistant Curate in St John the Evangelist Wick and St Peter and the Holy Rood, Thurso. Revd Jacqui du Rocher (above) was ordained Priest by Bishop John on 20 September in St Mary the Virgin, Dalkeith (Edinburgh) to serve as Associate Priest. Revd Dr James Clark-Maxwell (above) was ordained priest by Bishop Idris on 23 September in St John’s Dumfries (Glasgow and Galloway) to serve as Associate Priest. Photo taken by Harriet Oxley. Caroline Longley (above right) was licensed as a Lay Reader by Bishop John on 25 September in the Church of the Good Shepherd, Murrayfield (Edinburgh), the church in which she now serves. Revd Jonathan Livingstone (right) was ordained priest by Bishop Gregor on 26 September at St Mary’s Hamilton (Diocese of Glasgow and Galloway) where he serves as Associate Curate. Lee Johnston (left) was ordained Deacon by Bishop Gregor on 30 September in St Mary's Cathedral, Glasgow (Diocese of Glasgow and Galloway) to serve as Assistant Curate in the congregation of Christ Church Lanark. Andrew Philip (left in photo) and Oliver Clegg were ordained Deacon by Bishop John on 30 September in St Mary's Cathedral (Diocese of Edinburgh). Andy will serve as Chaplain in St Mary’s Cathedral and Ollie will continue to serve in the St Mungo’s Balerno Team. Megan Cambridge was licensed as a Lay Reader by Bishop Mark on Sunday 28 October in Holy Trinity Keith (Diocese of Moray, Ross and Caithness) to serve that congregation, part of the Isla-Deveron and Gordon Chapel cluster. -

David Steuart Erskine, 11Th Earl of Buchan: Founder of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

Society of Antiquaries of Scotland The Scottish Antiquarian Tradition: Essays to mark the bicentenary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1780-1980 Edited by A S Bell ISBN: 0 85976 080 4 (pbk) • ISBN: 978-1-908332-15-8 (PDF) Except where otherwise noted, this work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work and to adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: A Bell, A S (ed) 1981 The Scottish Antiquarian Tradition: Essays to mark the bicentenary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1780-1980. Edinburgh: John Donald. Available online via the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland: https://doi.org/10.9750/9781908332158 Please note: The illustrations listed on p ix are not covered by the terms of the Creative Commons license and must not be reproduced without permission from the listed copyright holders. The Society gratefully acknowledges the permission of John Donald (Birlinn) for al- lowing the Open Access publication of this volume, as well as the contributors and contributors’ estates for allowing individual chapters to be reproduced. The Society would also like to thank the National Galleries of Scotland and the Trustees of the National Museum of Scotland for permission to reproduce copyright material. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders for all third-party material reproduced in this volume. -

Transport and Environment Committee

Notice of meeting and agenda Transport and Environment Committee 10 am Tuesday 14 January 2014 Dean of Guild Court Room, City Chambers, High Street, Edinburgh This is a public meeting and members of the public are welcome to attend Contacts Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Tel: 0131 529 4240 / 0131 529 4106 1. Order of business 1.1 Including any notices of motion and any other items of business submitted as urgent for consideration at the meeting. 2. Declaration of interests 2.1 Members should declare any financial and non-financial interests they have in the items of business for consideration, identifying the relevant agenda item and the nature of their interest. 3. Deputations If any Minutes 4.1 Transport and Environment Committee 29 October 2013 (circulated) - submitted for approval as a correct record 5. Key decisions forward plan 5.1 Transport and Environment Committee Key Decisions Forward Plan (circulated) 6. Business bulletin 6.1 Transport and Environment Committee Business Bulletin (circulated) 7. Executive decisions 7.1 Transport and Environment Committee Policy Development and Review Sub- Committee Work Programme (circulated) 7.2 Local Transport Strategy 2014-2019 – report by the Director of Services for Communities (circulated) 7.3 Governance of Major Projects - Water of Leith and Braid Burn Flood Prevention Schemes – report by the Director of Services for Communities (circulated) 7.4 HS2 Phase Two Consultation "Better Connections" Response – report by the Director of Services for Communities -

Edinburgh Old Town Association Newsletter

Edinburgh Old Town Association Newsletter September 2018 Killing the goose that lays the golden eggs? At the time of writing the Fringe Festival was drawing to a close after what looks likely to be yet another record year in terms of the numbers of shows, performers and spectators. Part of the Fringe’s marketing this year has been what they described as “a small flock of golden pigeons … hidden in iconic Edinburgh landmarks”. The public were invited “to hunt these pigeons down and shoot them, with their phone camera”. This brings to mind the story of the goose that laid the golden eggs. As you’ll remember, the story was that a man and his wife owned a goose that every day would lay a golden egg. This made the couple rich but they decided they would get richer, faster if they could have all the golden eggs which they thought must be inside the goose. So, the couple killed the goose and cut her open, only to find that she had no golden eggs inside her at all, and now the precious goose was dead. The moral of the story is that too much greed results in nothing. That is a moral which should be taken to heart in Edinburgh. As we have said in previous Newsletters, events like the Fringe bring colour and interest to the city and those of us who live in or know the Old Town can derive great pleasure from sharing it with appreciative tourists. But the fragile Old Town environment can only cope with so much. -

The Liberal Party in Scotland, 1843- 1868: Electoral Politics and Party Development

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Liberal party in Scotland, 1843- 1868: electoral politics and party development Gordon F. Millar Departments of Scottish and Modern History University of Glasgow Presented for the degree of Ph.D. at the University of Glasgow © Gordon F. Millar October 1994 ProQuest Number: 10992153 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10992153 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Edinburgh Politics: 1832-1852

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. EDINBURGH POLITICS: 1832-1852 by Jeffrey Charles Williams Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh June 1972 Contents Preface Abbreviations One Social and Religious Groups in Early Victorian Edinburgh Two Political Groups in Early Victorian Edinburgh Three Whiggery Triumphant: 1832-1835 Four The Growth of Sectarian Politics: 1835-1841 Five The Downfall of the Whigs: 1841-184 7 Six The Breakdown of the Liberal Alliance: 184 7-1852 Seven Conclusion A!;)pendices 1. A Statistical Comparison of the Edinburgh Electorates of 183 5 and 1866 11. Electioneering in Edinburgh, 1832-1852 111. An Occupational Analysis of Town Councillors IV. An Occupational Analysis of the Edinburgh 'Radical Vote' of 1834 Bibliography ********* (i) Preface The Scottish Reform A~t of 1832 and the Scottish Municipal Reform Act of 1833 destroyed the domination of the Tory party over Edinburgh politics.