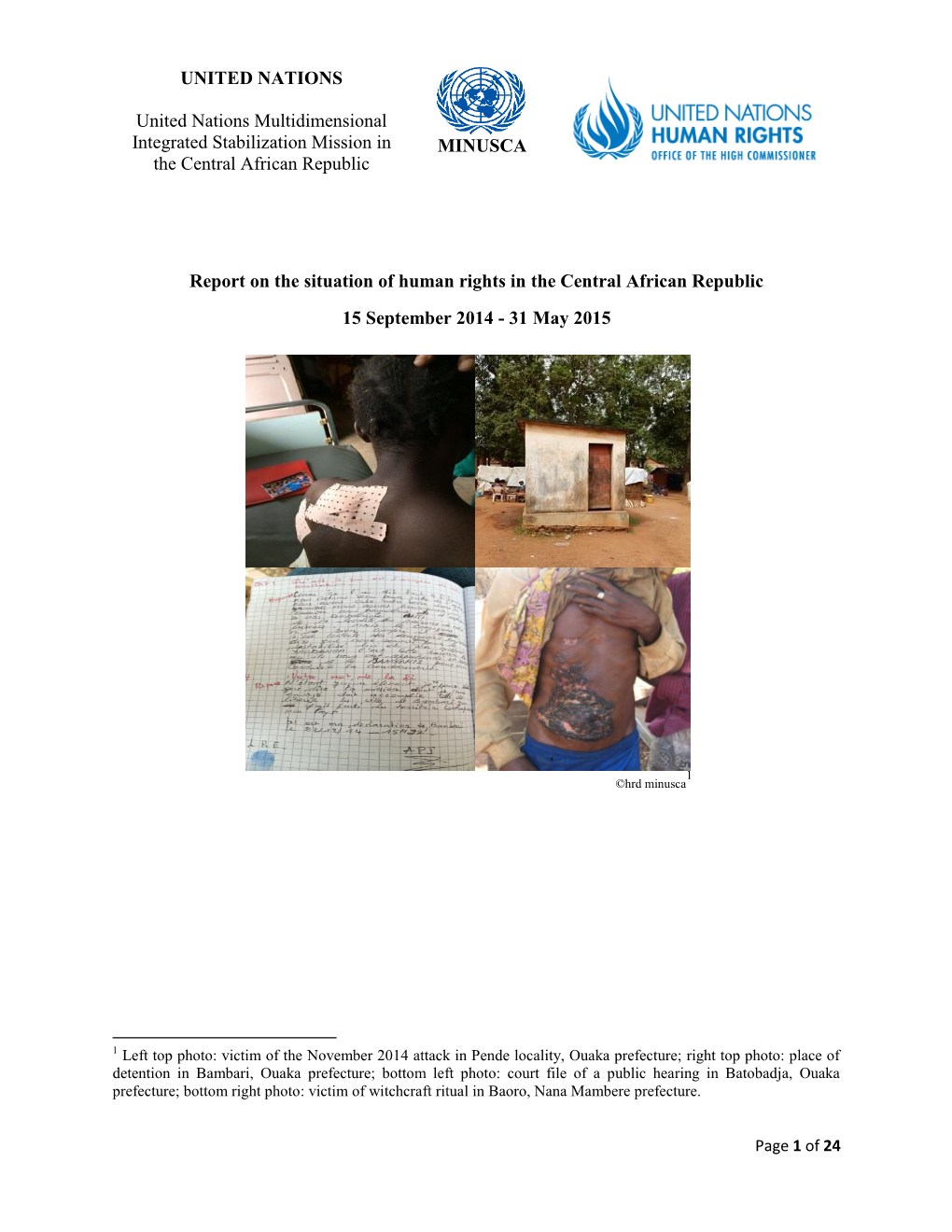

UNITED NATIONS United Nations Multidimensional Integrated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cie Française De L'ouhamé Et De La Nana (Oubangui-Tchad)

Mise en ligne : 21 février 2014. Dernière modification : 25 mai 2021. www.entreprises-coloniales.fr CIE FRANÇAISE DE L'OUHAMÉ ET DE LA NANA (COMOUNA) Coll. Serge Volper www.entreprises-coloniales.fr/empire/Coll._Serge_Volper.pdf COMPAGNIE FRANÇAISE DE L'OUHAMÉ ET DE LA NANA Société anonyme ———— Statuts déposés en l’étude de Me Victor Moyne, notaire à Paris, le 13 mars 1900 ——————— Capital social : deux millions de francs divisé en 4.000 actions de 500 francs chacune ACTION ABONNEMENT SEINE 2/10 EN SUS 5 c. POUR 100 fr. Siège social à Paris ——————— PART BÉNÉFICIAIRE AU PORTEUR Le président du conseil d’administration : Victor Flachon Un administrateur : Arthur Guinard Charles Skipper & East —————— Compagnie française de l’Ouhamé et de la Nana Constitution (La Cote de la Bourse et de la banque, 16 juin 1900) D’un acte reçu par Me Moyne, notaire à Paris, le 22 février 1900. M. Victor Flachon, publiciste, demeurant à Bois-Colombes (Seine), villa du Château, 9 ; M. Arthur Guinard, négociant, demeurant à Paris, avenue de l’Opéra, 8 ; M. Louis Mainard, publiciste, demeurant à Paris, boulevard Pereire, 55 bis , et M. François Renchet, administrateur de la Compagnie des Chemins de fer de Bayonne-Biarritz, demeurant à Paris, rue de Mathurins, 5, ont établi les statuts d’une société anonyme, conformément aux lois des 24 juillet 1867 et 1er août 1893. La société a pour objet : L’exploitation de la concession des terres domaniales au Congo français, accordée à M. Flachon (Victor), agissant au nom de M. de Behagle (Ferdinand), de M. Guinard (Arthur), Renchet (François) par décret de M. -

Imagining Peace Operations 2030

GCSP 25th Anniversary The New Normal? Imagining Peace Operations 2030 25 November 2020, GCSP, Online Speakers’ Biographies Mr Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah President, Centre for Strategies and Security in Sahel Sahara; Former UN Special Representative of the Secretary General to Burundi and Somalia; Former Minister for Foreign Affairs of Mauritania; and Member of the Panel of Experts on Peacebuilding University Studies Economy and Political Science in Grenoble and Paris. 1969 / 1984: Minister of Commerce and Transportatio Amb;assador to the United States; to the Benelux States and the European Union in Brussels, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. 1985 / 1996: United Nations as Director at Headquarters, New York and Special Representative to the Secretary General (SRSG) in conflict affected Burundi 1993 / 95. 1996 / 2002, World Bank as the manager of the Think Tank Global Coalition for Africa chaired by Robert Mc Namara in Washington DC. 2002 / 2011 back to the United Nations as the Special Representative of the Secretary General to West Africa and later to Somalia. Then to the Headquarters for Special missions. In 2015 and 2019 member of the UN Secretary General Advisory Group of Experts on the Review of Peace Building Architecture and leader of the Secretary General Team to review the UN Office for the Central Africa Region (UNOCA). Founding member of Transparency International and is member of its Consultative Council. He also is member of a number of Advisory Boards of profits and non-profits organizations. He has published two books on his UN experience on conflict management: la Diplomatie Pyromane in 1996, Calmann Levy France; "Burundi on the Brink in 2000, US Institute of Peace and recently his Mémoires: ‘’Plutôt mourir que faillir " Ed Descartes et Cie, Paris 2017 translated in Arabic 2020. -

PLAN DE RÉPONSE HUMANITAIRE République Centrafricaine

CYCLE DE PROGRAMMATION PLAN DE RÉPONSE HUMANITAIRE 2020 HUMANITAIRE PUBLIÉ EN DECEMBRE 2019 République Centrafricaine 1 PLAN DE REPONSE HUMANITAIRE 2020 | À PROPOS Pour consulter les mises à jour À propos les plus récentes : Ce document est consolidé par OCHA pour le compte de l’Équipe OCHA coordonne l’action humanitaire pour humanitaire pays et des partenaires humanitaires. Il présente les priorités garantir que les personnes affectées par une et les paramètres de la réponse stratégique de l’Équipe humanitaire crise reçoivent l’assistance et la protection dont elles ont besoin. OCHA s’efforce pays, basés sur une compréhension partagée de la crise, énoncés dans de surmonter les obstacles empêchant l’Aperçu des besoins humanitaires. l’assistance humanitaire de joindre les Les désignations employées et la présentation des éléments dans le personnes affectées par des crises et est chef présent rapport ne signifient pas l’expression d’une quelque opinion que de file dans la mobilisation de l’assistance et de ressources pour le compte du système ce soit de la Partie du Secrétariat des Nations unies concernant le statut humanitaire juridique d’un pays, d’un territoire, d’une ville ou d’une zone ou de leurs autorités ou concernant la délimitation de frontières ou de limites. www.unocha.org/car twitter: @OCHA_CAR PHOTO DE COUVERTURE @UNICEF CAR / B. Matous Humanitarian Réponse est destiné à être le site Web central des outils et des services de Gestion de l’information permettant l’échange d’informations entre les clusters et les membres du IASC intervenant dans une crise. car.humanitarianresponse.info Humanitarian InSight aide les décideurs en leur donnant accès à des données humanitaires essentielles. -

United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations TABLE of CONTENTS Foreword / Messages the Police Division in Action

United Nations United Department of Peacekeeping Operations of Peacekeeping Department 12th Edition • January 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword / Messages The Police Division in Action 01 Foreword 22 Looking back on 2013 03 From the Desk of the Police Adviser From many, one – the basics of international 27 police peacekeeping Main Focus: Une pour tous : les fondamentaux de la 28 police internationale de maintien Vision and Strategy de la paix (en Français) “Police Week” brings the Small arms, big threat: SALW in a 06 30 UN’s top cops to New York UN Police context 08 A new vision for the UN Police UNPOL on Patrol Charting a Strategic Direction 10 for Police Peacekeeping UNMIL: Bringing modern forensics 34 technology to Liberia Global Effort Specific UNOCI: Peacekeeper’s Diary – 36 inspired by a teacher Afghan female police officer 14 literacy rates improve through MINUSTAH: Les pompiers de Jacmel mobile phone programme 39 formés pour sauver des vies sur la route (en Français) 2013 Female Peacekeeper of the 16 Year awarded to Codou Camara UNMISS: Police fingerprint experts 40 graduate in Juba Connect Online with the 18 International Network of UNAMID: Volunteers Work Toward Peace in 42 Female Police Peacekeepers IDP Camps Facts, figures & infographics 19 Top Ten Contributors of Female UN Police Officers 24 Actual/Authorized/Female Deployment of UN Police in Peacekeeping Missions 31 Top Ten Contributors of UN Police 45 FPU Deployment 46 UN Police Contributing Countries (PCCs) 49 UN Police Snap Shot A WORD FROM UNDER-SECRETARY-GENERAL, DPKO FOREWORD The changing nature of conflict means that our peacekeepers are increasingly confronting new, often unconventional threats. -

Central African Republic Emergency Situation UNHCR Regional Bureau for Africa As of 26 September 2014

Central African Republic Emergency Situation UNHCR Regional Bureau for Africa as of 26 September 2014 N'Djamena UNHCR Representation NIGERIA UNHCR Sub-Office Kerfi SUDAN UNHCR Field Office Bir Nahal Maroua UNHCR Field Unit CHAD Refugee Sites 18,000 Haraze Town/Village of interest Birao Instability area Moyo VAKAGA CAR refugees since 1 Dec 2013 Sarh Number of IDPs Moundou Doba Entry points Belom Ndele Dosseye Sam Ouandja Amboko Sido Maro Gondje Moyen Sido BAMINGUI- Goré Kabo Bitoye BANGORAN Bekoninga NANA- Yamba Markounda Batangafo HAUTE-KOTTO Borgop Bocaranga GRIBIZI Paoua OUHAM 487,580 Ngam CAMEROON OUHAM Nana Bakassa Kaga Bandoro Ngaoui SOUTH SUDAN Meiganga PENDÉ Gbatoua Ngodole Bouca OUAKA Bozoum Bossangoa Total population Garoua Boulai Bambari HAUT- Sibut of CAR refugees Bouar MBOMOU GadoNANA- Grimari Cameroon 236,685 Betare Oya Yaloké Bossembélé MBOMOU MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO Zemio Chad 95,326 Damara DR Congo 66,881 Carnot Boali BASSE- Bertoua Timangolo Gbiti MAMBÉRÉ- OMBELLA Congo 19,556 LOBAYE Bangui KOTTO KADÉÏ M'POKO Mbobayi Total 418,448 Batouri Lolo Kentzou Berbérati Boda Zongo Ango Mbilé Yaoundé Gamboula Mbaiki Mole Gbadolite Gari Gombo Inke Yakoma Mboti Yokadouma Boyabu Nola Batalimo 130,200 Libenge 62,580 IDPs Mboy in Bangui SANGHA- Enyelle 22,214 MBAÉRÉ Betou Creation date: 26 Sep 2014 Batanga Sources: UNCS, SIGCAF, UNHCR 9,664 Feedback: [email protected] Impfondo Filename: caf_reference_131216 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC The boundaries and names shown and the OF THE CONGO designations used on this map do not imply GABON official endorsement or acceptance by the United CONGO Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. -

Reconciling the Protection of Civilians and Host-State Support in UN Peacekeeping

MAY 2020 With or Against the State? Reconciling the Protection of Civilians and Host-State Support in UN Peacekeeping PATRYK I. LABUDA Cover Photo: Elements of the UN ABOUT THE AUTHOR Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s PATRYK I. LABUDA is a Postdoctoral Scholar at the (MONUSCO) Force Intervention Brigade Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and a Non-resident and the Congolese armed forces Fellow at the International Peace Institute. The author’s undertake a joint operation near research is supported by the Swiss National Science Kamango, in eastern Democratic Foundation. Republic of the Congo, March 20, 2014. UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper represent those of the author The author wishes to thank all the UN officials, member- and not necessarily those of the state representatives, and civil society representatives International Peace Institute. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide interviewed for this report. He thanks MONUSCO in parti - range of perspectives in the pursuit of cular for organizing a workshop in Goma, which allowed a well-informed debate on critical him to gather insights from a range of stakeholders.. policies and issues in international Special thanks to Oanh-Mai Chung, Koffi Wogomebou, Lili affairs. Birnbaum, Chris Johnson, Sigurður Á. Sigurbjörnsson, Paul Egunsola, and Martin Muigai for their essential support in IPI Publications organizing the author’s visits to the Central African Adam Lupel, Vice President Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Albert Trithart, Editor South Sudan. The author is indebted to Namie Di Razza for Meredith Harris, Editorial Intern her wise counsel and feedback on various drafts through - out this project. -

State of Anarchy Rebellion and Abuses Against Civilians

September 2007 Volume 19, No. 14(A) State of Anarchy Rebellion and Abuses against Civilians Executive Summary.................................................................................................. 1 The APRD Rebellion............................................................................................ 6 The UFDR Rebellion............................................................................................ 6 Abuses by FACA and GP Forces........................................................................... 6 Rebel Abuses....................................................................................................10 The Need for Protection..................................................................................... 12 The Need for Accountability .............................................................................. 12 Glossary.................................................................................................................18 Maps of Central African Republic ...........................................................................20 Recommendations .................................................................................................22 To the Government of the Central African Republic ............................................22 To the APRD, UFDR and other rebel factions.......................................................22 To the Government of Chad...............................................................................22 To the United Nations Security -

9 Interpol and the Emergence of Global Policing

Stalcup, Meg. 2013. “Interpol and the Emergence of Global Policing.” In Policing and Contemporary Governance: The Anthropology of Police in Practice. ed. William Garriott, 231- 261. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. Reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan. This extract is taken from the author's original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive version of this piece may be found in Policing and Contemporary Governance edited by William Garriott, which can be purchased from http://www.palgrave.com. 9 Interpol and the Emergence of Global Policing Meg Stalcup Introduction “The New Interpol is not simply a collection of databases and communication networks,” said Secretary General Ronald K. Noble to national representatives at Interpol’s 2002 annual assembly.1 “You have heard me use the expression—the Interpol police family. It is an expression that we wish to turn into reality” (Noble 2002). The organization, dedicated to police cooperation, had previously taken four to six months to transmit even high-profile requests for arrest between member nations. Notices were sent as photocopies, mailed by the cheapest and lowest priority postage available (ibid.).2 Modernization and reorganization, however, had just cut the time for priority notices to a single day. The Secretary General’s call for “police family” named the organization’s ambition to create fellowship through these exchanges. Interpol is not a police force. Neither national nor international laws are enforced by Interpol directly, nor do staff and seconded police officers working under its name make a state’s claim to the right of physical coercion (vide Weber), or to powers of investigation and arrest. -

Central African Republic: Floods

DREF operation n° MDRCF007 Central African Republic: GLIDE n° FL-2010-000168-CAF Floods 26 August, 2010 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent emergency response. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. CHF 145,252 (USD 137,758 or EUR 104,784) has been allocated from the IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the Central African Red Cross Society (CARCS) in delivering immediate assistance to some 330 displaced families, i.e. 1,650 beneficiaries. Un- earmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: The rainy season that started in July in Central African Republic (CAR) reached its peak on 7 August, 2010 when torrential rains caused serious floods in Bossangoa, a Northern Evaluation of the situation in Bossangoa by CAR Red locality situated 350 km from Bangui, the capital Cross volunteers / Danielle L. Ngaissio, CAR Red Cross city. Other neighbouring localities such as Nanga- Boguila and Kombe, located 187 and 20 km respectively from Bossangoa have also been affected. Damages registered include the destruction of 587 houses (330 completely), the destruction of 1,312 latrines, the contamination of 531 water wells by rain waters and the content of the latrines that have been destroyed. About 2,598 people (505 families) have been affected by the floods. -

Central African Republic: Who Has a Sub-Office/Base Where? (05 May 2014)

Central African Republic: Who has a Sub-Office/Base where? (05 May 2014) LEGEND DRC IRC DRC Sub-office or base location Coopi MSF-E SCI MSF-E SUDAN DRC Solidarités ICRC ICDI United Nations Agency PU-AMI MENTOR CRCA TGH DRC LWF Red Cross and Red Crescent MSF-F MENTOR OCHA IMC Movement ICRC Birao CRCA UNHCR ICRC MSF-E CRCA International Non-Governmental OCHA UNICEF Organization (NGO) Sikikédé UNHCR CHAD WFP ACF IMC UNDSS UNDSS Tiringoulou CRS TGH WFP UNFPA ICRC Coopi MFS-H WHO Ouanda-Djallé MSF-H DRC IMC SFCG SOUTH FCA DRC Ndélé IMC SUDAN IRC Sam-Ouandja War Child MSF-F SOS VdE Ouadda Coopi Coopi CRCA Ngaounday IMC Markounda Kabo ICRC OCHA MSF-F UNHCR Paoua Batangafo Kaga-Bandoro Koui Boguila UNICEF Bocaranga TGH Coopi Mbrès Bria WFP Bouca SCI CRS INVISIBLE FAO Bossangoa MSF-H CHILDREN UNDSS Bozoum COHEB Grimari Bakouma SCI UNFPA Sibut Bambari Bouar SFCG Yaloké Mboki ACTED Bossembélé ICRC MSF-F ACF Obo Cordaid Alindao Zémio CRCA SCI Rafaï MSF-F Bangassou Carnot ACTED Cordaid Bangui* ALIMA ACTED Berbérati Boda Mobaye Coopi CRS Coopi DRC Bimbo EMERGENCY Ouango COHEB Mercy Corps Mercy Corps CRS FCA Mbaïki ACF Cordaid SCI SCI IMC Batalimo CRS Mercy Corps TGH MSF-H Nola COHEB Mercy Corps SFCG MSF-CH IMC SFCG COOPI SCI MSF-B ICRC SCI MSF-H ICRC ICDI CRS SCI CRCA ACF COOPI ICRC UNHCR IMC AHA WFP UNHCR AHA CRF UNDSS MSF-CH OIM UNDSS COHEB OCHA WFP FAO ACTED DEMOCRATIC WHO PU-AMI UNHCR UNDSS WHO CRF MSF-H MSF-B UNFPA REPUBLIC UNICEF UNICEF 50km *More than 50 humanitarian organizations work in the CAR with an office in Bangui. -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

International Activity Report 2017

INTERNATIONAL ACTIVITY REPORT 2017 www.msf.org THE MÉDECINS SANS FRONTIÈRES CHARTER Médecins Sans Frontières is a private international association. The association is made up mainly of doctors and health sector workers, and is also open to all other professions which might help in achieving its aims. All of its members agree to honour the following principles: Médecins Sans Frontières provides assistance to populations in distress, to victims of natural or man-made disasters and to victims of armed conflict. They do so irrespective of race, religion, creed or political convictions. Médecins Sans Frontières observes neutrality and impartiality in the name of universal medical ethics and the right to humanitarian assistance, and claims full and unhindered freedom in the exercise of its functions. Members undertake to respect their professional code of ethics and to maintain complete independence from all political, economic or religious powers. As volunteers, members understand the risks and dangers of the missions they carry out and make no claim for themselves or their assigns for any form of compensation other than that which the association might be able to afford them. The country texts in this report provide descriptive overviews of MSF’s operational activities throughout the world between January and December 2017. Staffing figures represent the total full-time equivalent employees per country across the 12 months, for the purposes of comparisons. Country summaries are representational and, owing to space considerations, may not be comprehensive. For more information on our activities in other languages, please visit one of the websites listed on p. 100. The place names and boundaries used in this report do not reflect any position by MSF on their legal status.