University of Sargodha Sargodha 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examination Centers & Venue Details

ISQ examination Winter– 2017 shall commence from Monday, October 23,2017 and will end on Friday October 27,2017. Examination Centers & Venue Details S#. Centre Name Examination Venue United Bank Limited, Khalifa Main Branch,Mezzanine floor, Hamad Suhail Al Khaily 1 Abu Dhabi Bulding,Khalifa Bin Zayed, The First Street,Next to TRYP by Wyndham Hotel, Abu Dhabi, UAE 2 Bahawalpur Govt. Abbasiya Higher Secondary School, Model Town-A, Bahawalpur. 3 D.I Khan State Bank of Pakistan, SBP BSC (Bank), Shammi Road, Dera Ismail Khan. 4 Faisalabad State Bank of Pakistan, SBP BSC (Bank), Old Banking Hall, Faisalabad 5 Gilgit Hayat Shaheed Army Public School, NLI Commercial Market, Gilgit. 6 Gujranwala University of Sargodha, Gujranwala campus, Sialkot bypass, Lahore Road, Gujranwala. ETECH-College of Business and Information Technology, Near Eid Gah Masjid, G.T Road, 7 Gujrat Gujrat 8 Hyderabad State Bank Of Pakistan, SBP BSC (Bank), Thandi Sarak, Hyderabad 9 Islamabad Grafton College of Management Sciences, No. 06, Park Road, Chak Shahzad, Islamabad 10 Karachi Dawood Public School, Plot # ST-1, Dawood Cooperative Society, Bahadurabad, Karachi. 11 Lahore State Bank of Pakistan, SBP-BSC (Bank) 56 Shahra-e- Quaid-e- Azam, Lahore Mirpur University of Science & Technology, Examination Hall-Electrical Engineering 12 Mirpur AK department, Allama Iqbal Road, Mirpur Azad (AK). 13 Multan Government College, Civil Lines, Near Chowk Kutchehry, Multan. 14 Muzaffarabad (AK) State Bank of Pakistan, SBP BSC (Bank), Uppar Chattar, Muzaffarabad (AK) 15 Peshawar City University of Science & Information Technology, Dalazak Road, Peshawar 16 Quetta State Bank Of Pakistan, SBP BSC (Bank), Shahra-e-Gulistan, Quetta Cantt. -

Legal Practitioners & Bar Councils Act, 1973

144 Pakistan Bar Council Legal Education Rules, 2015 PAKISTAN BAR COUNCIL NOTIFICATION December 19, 2015 S.R.O. 1265(1)/2015.—Whereas the “Pakistan Bar Council Legal Education Rules” earlier promulgated and notified by the Pakistan Bar Council way back in 1978 do not cater present day’s needs, require to be reformed and updated; And whereas the existing three sets of Rules on the subject of legal education i.e. the “Pakistan Bar Council Legal Education Rules, 1978”, the “Affiliation of Law Colleges Rules” and the “Pakistan Bar Council (Recognition of Universities) Rules, 2005” are to be reviewed and consolidated in one set of uniformed Rules; And whereas the constant deterioration of standard and quality of legal education because of mushroom growth of law colleges and even the Universities, in private sector, necessitates strict check and control over the Universities and degree awarding Institutions, imparting legal education, and the private law colleges; Therefore, the Pakistan Bar Council in exercise of powers conferred upon it under Sections 13(j) & (k), 26(c) (iii) and 55(q) of the Legal Practitioners & Bar Councils Act, 1973 and all other enabling provisions in that behalf, hereby promulgates and notifies the following Rules: THE PAKISTAN BAR COUNCIL LEGAL EDUCATION RULES , 2015 CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY 1. Short title and commencement:- (i) These Rules may be called the “Pakistan Bar Council Legal Education Rules, 2015”. Pakistan Bar Council Legal Education Rules, 2015 145 (ii) They shall come into force at once. 2. Overriding effect:- The provisions of these Rules shall have overriding effect notwithstanding anything inconsistent therewith contained in any other law and Rules for the time being in force. -

Sr# University Focal Person with Contacts 1 University of Balochistan

Sr# University Focal person with contacts 1 University of Balochistan, Quetta Mr. Abdul Malik, [email protected], [email protected] Ph: 081-9211836 & Fax# 081-9211277 AmanUllah Sahib (Principal Law College) 2 BUITEMS, Quetta Ms. Kinza (Manager Financial Assistance) [email protected] 3 Sardar Bhadur Khan Women Ms. Huma Tariq (Assistant Registrar Financial Aid Office) University, Quetta [email protected]; Ph:0819213309 4 University of Loralai Mr. Noor ul Amin Kakar (Registrar) [email protected] 5 University of Turbat, Turbat Mr. Ganguzar Baloch (Deputy Registrar) [email protected] 6 Balochistan University of Engr. Mumtaz Ahmed Mengal Engineering & Technology Khuzdar [email protected] Ph: 0848550276 7 Lasbela University of Water & Haji Fayyaz Hussain(UAFA) Marine sciences, Lasbela [email protected] Office: Ph: 0853-610916 Dr.Gulawar Khan [email protected] 8 National University of Modern Prof. Usman Sahib (Regional director) Languages (NUML), Quetta Campus [email protected]; [email protected] Ph: 081-2870212 9 University of Peshawar, Peshawar Mr. Fawad Khattak (Scholarship Officer) [email protected], Ph: 091-9216474 10 Khyber Medical University, Mr. Fawad Ahmed (Assistan Director Admissions) Peshawar [email protected] Ph: 091-9217703 11 Islamia College, Peshawar Mr.Sikandar Khan (Director Students Affairs) [email protected] 12 Kohat University of science and Mr. Zafar Khan (Director Finance) Technology(KUST), Kohat [email protected], Rahim Afridi (Dealing Assistant)[email protected] 13 University of Agriculture, Peshawar Prof. Dr. Muhammad Jamal Khan [email protected]; [email protected] 14 University of Engineering & Mr. Nek Muhammad Khan (Director Finance/Treasurer) Technology, Peshawar [email protected] Ph: 091-9216497 15 IM Sciences, Peshawar Mr. -

ARSLAN SHEIKH Assistant Librarian COMSATS University Islamabad, Park Road, Islamabad-Pakistan

ARSLAN SHEIKH Assistant Librarian COMSATS University Islamabad, Park Road, Islamabad-Pakistan. +92-51-90495069 | +92-321-9423071 | [email protected] : https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2661-6383 Career Objective To learn and grow in the field of Library and Information Management, being affiliated with academic as well as professional organizations. Education PhD in Library & Information Science - (In Progress) Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany MS in Library & Information Science - 2019 CGPA 3.31/4.00 Sarhad University of Science & Information Technology, Peshawar Master of Library & Information Science - 2006 CGPA 3.26/4.00 University of the Punjab, Lahore Work Experience Assistant Librarian - 09/2009 to Present COMSATS University Islamabad Reference and research services Electronic document delivery Support of researchers in literature searching Guidance in writing research articles/theses and dissertations Help in referencing and citation management Guidance of researchers in publishing their research Plagiarism detection in theses, articles & academic assignments Editor, LIS Bulletin (a quarterly newsletter) Visiting Lecturer - 10/2020 to 03/2021 Department of Information Management, University of Sargodha Taught Course (Information Technology: Concepts and Applications) Taught Course (Library Automation Systems) Assistant Librarian - 05/2008 to 08/2009 National University (FAST), Islamabad In charge circulation, technical and reference services Digital reference services Handling of digital resources Orientation for new library patrons Compiler, “Faculty Annual Research Publications Report” Librarian - 11/2006 to 05/2008 Hajvery University (HU), Lahore Pioneer Librarian of “Euro Campus Library” Management of all library operations Library automation Serials management Acquisition of library materials Librarian (Intern) - 06/2006 to 08/2006 Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), Lahore Research Journal Articles 1. -

Federal Capital, Islamabad Punjab Province

APPROVED PUBLIC SECTOR UNIVERSITIES / COLLEGES & THEIR CAMPUSES* Federal Capital, Islamabad Sr. # Universities / Colleges Designated Branches 1 Air University, Islamabad. Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 2 Bahria University, Islamabad. Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 3 COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad. Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 4 Federal Urdu University of Arts, Sci. & Tech., Islamabad. Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 5 International Islamic University, Islamabad Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 6 National University of Medical Sciences, Islamabad Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 7 National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad. Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 8 National University of Science & Technology, Islamabad Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 9 National Defence University, Islamabad Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 10 Pakistan Institute of Engineering & Applied Sciences, Islamabad Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 11 Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) Islamabad Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 12 Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 13 Institute of Space Technology, Islamabad. Foreign Office Branch Islamabad 14 Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Medical University, Islamabad Foreign Office Branch Islamabad Punjab Province 1 Allama Iqbal Medical College, Lahore Main Branch Lahore. 2 Fatima Jinnah Medical College for Women, Lahore Main Branch Lahore. 3 Government College University, Lahore Main Branch Lahore. 4 King Edward Medical College, Lahore Main Branch Lahore. 5 Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore Main Branch Lahore. 6 Lahore College for Women University, Lahore. Main Branch Lahore. 7 National College of Arts, Lahore. Main Branch Lahore. 8 University of Education, Lahore. Main Branch Lahore. 9 University of Health Sciences, Lahore Main Branch Lahore. 10 University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore. Main Branch Lahore. Sr. # Universities / Colleges Designated Branches 11 Virtual University of Pakistan, Lahore. -

English Last Final.Cdr

A quarterly news publication of Sargodha University NEWSLETTER October-December 2018 Volume 12, Issue 4 Sargodha University has more than a Honouring Faculty century long history, first established as a school in Shahpur, a nearby town of Sargodha city, which then became Welcoming Alumni De'Montmorency College in 1929, renamed as Government College Sargodha in 1946, and chartered as a university in 2002. The Alumni Association of University of Sargodha was established in 2017 to resume contact with the graduates of both Government College Sargodha and the University, many of whom have rendered exemplary services in politics, civil and military services bureaucracy, academia, business and other spheres of public life. “I am so happy to see so many graduates of the College, some of whom were students during my tenure as Principal,” said Sahibzada Abdur Rasool, adding: “Alumni's engagement with this university is critical not only for inspiring our talented but generally directionless youth but also Former Governor Sindh and Interior Minister General Moinddin Haider, developing the institution in meaningful an alumnus of Government College Sargodha, and Vice Chancellor Dr Ishtiaq Ahmad ways.” presenting bouquet to Dr Saeed Akram Bhatti upon his retirement On the occasion, vibrant festivities and t the end of each year, Sargodha College Sargodha Sahibzada Abdur Rasool, colouful musical performances by students University hosts a dinner also a prominent historian and author. entertained the worthy guests, whereas Areception for its faculty and staff Hence, the reception not only reflected the d o c u m e n t a r y f i l m s , e v i n c i n g t h e to pay tributes to its professors retired in the emotive expressions of gratitude to the worthwhile contributions of the retiring past year for their distinctive service at the departing members of the senior faculty but faculty along with their recorded interviews, University. -

MBBS/BDS Admissions in Medical / Dental Institutions of the Punjab

1 MBBS/BDS Admissions in Medical / Dental Institutions of the Punjab FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQS) 2 Q.1 I have passed my HSSC Pre-Medical/Equivalent examination. How can I get admission to a government (Public Sector) medical/dental college in Punjab? Ans: It’s a two steps process: First, you will have to appear in the Admission Test of the Punjab; Second, if you secure a minimum percentage of aggregate marks as set by the Provincial Admission Committee (adding the weightage of matriculation, HSSC and Entrance Test scores according to the formula of Pakistan Medical and Dental Council) then you will be eligible to apply for admission to a public sector medical/dental institution in Punjab on open merit basis. In 2017, the minimum aggregate percentage required to apply for public sector institutions was 83.4000%. Q.2 What is the eligibility criterion for appearing in the Admission Test? Ans: Any candidate who has passed Intermediate/HSSC Pre-Medical /Equivalent examination from a Board/University with at least 60% marks (unadjusted) or who is awaiting result of HSSC Part-II/Equivalent examination can apply. His subjects must include Biology and Chemistry. Q.3 Who conducts the Provincial Admission Test and how many times in a year this test is arranged? Ans: The University of Health Sciences (UHS) Lahore (www.uhs.edu.pk) conducts the Admission Test only once a year. A candidate has to appear in the test of the year in which he/she is applying for admissions. The result of Admission Test is valid for one year only. -

Careers in Early Childhood Education (ECE)

PREFACE At every stage of transition in students academics, choosing a right path is like nightmare for both student and parents. Which field is best in the market, what career path my friends are selecting, what school/ college/ university should I select, what my parents want to become? Many of such question arises at this stage adding up to it, current global market trend of emergence of new fields and fading away old fields is very short span of time, selection of career path is now became a never ending puzzle. Simple answer to this question lies is PLANNING. However planning your career goals one should be well aware of their interest, skills, ability, values and a clear picture of possible career options. This handbook is the first step of my project ―Inspire the Learning Minds‖ towards career guidance, focused on a) To inform readers about the basic step for identifying there interest, skills, ability and values to make right career choice b) To give readers an overall picture of fields and possible careers I wish all my readers all the very best in choosing the right career path!! Start of a career is the beginning of a new life; it could be very fruitful, you may find absolutely unexpected yet amazing opportunities. And it could be as frustrating as hell. Sohail Merchant SOHAIL MERCHANT’S WORKSHOP SERIES WORKSHOPS: 1. Creativity & Innovation 2. Problem Solving & Decision Making 3. Examination Techniques 4. Interviewing Skills 5. Negotiation Skills 6. How to finance short term needs of your business 7. Presentation Skills 8. -

Curriculum Vitae: Dr. Ashfaq Ahmad

Curriculum Vitae: Dr. Ashfaq Ahmad Name: Ashfaq Ahmad Designation: Associate Professor Office: Room No. 110, Nazir Block, Hailey College of Commerce, University of the Punjab, Lahore Emails- Official: [email protected] /[email protected]. Personal:[email protected] Phone No. Official: +92 42 99230327 (Ext. 177). Personal: +92 300 4448426/0331 4448426 Dr. Ashfaq Ahmad has more than 20 Years’ experience in teaching, research, trainings and administrative assignments at higher education sector/professional bodies of Pakistan. Presently, Dr Ahmad is serving as Associate Professor at Hailey College of Commerce, University of the Punjab Lahore. Prior to this position/assignment he also served as: Associate Professor & Head at Management Sciences Department, Bahria University Associate Professor & Acting Director at Institute of Business & Management, University of Engineering & Technology, Lahore Assistant Professor & Head of Noon Business School at University of Sargodha, Sargodha Assistant Professor & Head of Commerce Department at University of Sargodha, Sargodha Assistant Professor & Head of Business Administration at University of Sargodha, Sargodha Superintendent Boys Hostels at University of Sargodha, Sargodha Lecturer at Department of Business Administration, University of Sargodha and other professional bodies since 2000. Dr. Ahmad attained the entire academic qualification with first class by qualifying PhD (Management Sciences-Finance), M. Phil (Business Administration-Finance) having Commerce education (M.Com; B.com & D.Com) and CA (partially qualified). He has conducted training sessions at various professional bodies including: Institute of Bankers of Pakistan and NIBAF State Bank of Pakistan Pakistan Institute of Development Economics Pakistan Agriculture Research Council Small & Medium Enterprise Development Authority Albaraka Islamic Bank Private Limited Pakistan Post (Headquarter) etc. -

Curriculum Vitae of Dr

1 Curriculum Vitae of Dr. Bilal Saeed Khan (Entomologist) 1. Name: : Dr. BILAL SAEED KHAN S/o Muhammad Saeed Khan 2. Mailing Address : Lecturer, Department of Entomology, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan. Phone office: 0092-41-9200161-70/2906 Res: 0092-41-2402627 Mob#: 00 92 321-6646852, Fax: 0092 41 9201083 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 3. Date of Birth : 01-09-1978 4. Nationality : Pakistani 5. NIC # & NTN # : 33100-1747587-3 & 3372223-4 6. Domicile : Jhang/ Punjab/ Pakistan 7. E ducational Record: Examination Institution Attended Year of CGPA/Marks Div. / %age Passing Obtained S.S.C. Laboratory High School, 1994 606/850 1st Science group Faisalabad/ Punjab. F.Sc. Govt. College of Science, 1996 618+20= 2nd Pre-medical Faisalabad. 638/1100 B.Sc. (Hons.) University of Agriculture, 2000 3.60/4.00 1st Agri. Entomology Faisalabad. 3014/4040 74.60% M.Sc. (Hons.) University of Agriculture, 2002 3.63/4.00 1st Agri. Entomology Faisalabad. 702/900 78% PhD University of Agriculture, 2009 A Pass Faisalabad. URL: http://www.uaf.edu.pk/employees.aspx?param=DEPT&id=6&id1=23 2 8. Field of Specialization PhD Entomology (2009) Systematics, Biology and Predatory efficacy of Stigmaeid mites (Stigmaeidae: Acari) from Punjab-Pakistan. MSc. (Hons) Entomology (2002) Effect of abiotic factors against the infestation of bollworm complex on different nectarid & nectariless varieties of cotton under unsprayed conditions. 9. Service Experience (1) Research associate (Bio-control Lab) (01-06-2003 to 16-07-2003) (2) Lecturer (Per lecture basis) (17-07-2003 to 28-03-2007) (3) Lecturer (Contract basis) (29-03-2007 to 04-03-2008) (4) Lecturer (Regular basis) (05-03-2008 to 20-06-2009) (5) Assistant Professor (Adhoc basis) (21-06-2009 to 20-12-2010) (6) Lecturer (Regular basis) as per University policy (21-12-2010 to date) 10. -

List of Participating Institutions

List of Participating Institutions - NGIRI S.No Institution Campus City Province 1 Abasyn University Islamabad Islamabad Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 2 Abasyn University Peshawar Peshawar Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 3 Abbottabad University of Science And Technology Havelian Abbotabad Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 4 Abdul Wali Khan University Garden Mardan Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 5 Air University Islamabad Islamabad Federal Capital 6 Al-Hamd Islamic University Quetta Quetta Balochistan 7 Allama Iqbal Open University Main Islamabad Federal Capital 8 Army Public College of Management and Sciences APCOM, Rawalpind Rawalpindi Punjab 9 Bahauddin Zakariya University Main Multan Punjab 10 Bahria University Karachi Karachi Federal Capital 11 Bahria University Main Islamabad Federal Capital 12 Bahria University Lahore Lahore Punjab Balochistan University of Engineering and 13 Khuzdar Khuzdar Balochistan Information Technology Balochistan University of Information Technology, 14 Quetta Quetta Balochistan Engineering & Management Sciences 15 Barret Hodgson University The Salim Habib Karachi Sindh 16 Benazir Bhutto Shaheed University Karachi Karachi Sindh 17 Capital University of Science and Technology Main Islamabad Federal Capital 18 CECOS University of IT & Emerging Sciences Main Peshawar Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 19 City University of Science & Information Technology Peshawar Peshawar Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 20 COMSATS University of Information Technology Abbottabad Abbotabad Federal Capital 21 COMSATS University of Information Technology Attock Attock Federal Capital 22 COMSATS University -

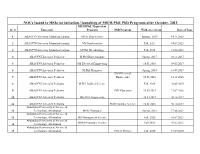

Nocs Issued to Heis for Initiation / Launching of MS/M.Phil/ Phd Programs After October, 2013 MS/M.Phil / Equivalent Sr

NOCs Issued to HEIs for initiation / launching of MS/M.Phil/ PhD Programs after October, 2013 MS/M.Phil / Equivalent Sr. # University Program PhD Program With effect from Date of Issue 1 ABASYN University Islamabad campus MS in Data Science January, 2019 14.11.2018 2 ABASYN University Islamabad campus MS Biochemistry Fall, 2021 14.07.2021 3 ABASYN University Islamabad campus M.Phil Microbiology Fall, 2018 31.08.2018 4 ABASYN University Peshawar M.Phil Biotechnology Spring, 2017 01.11.2017 5 ABASYN University Peshawar MS Electrical Engineering 18.01.2016 09.05.2017 6 ABASYN University Peshawar M.Phil Pharmacy Spring, 2014 18.09.2017 PhD Electrical 7 ABASYN University Peshawar Engineering 18.01.2016 18.11.2016 8 ABASYN University Peshawar M.Phil Political Science Fall, 2019 20.05.2019 9 ABASYN University Peshawar PhD Education 10.03.2015 22.07.2016 10 ABASYN University Peshawar MS Civil Engineering 28.03.2017 30.10.2017 11 ABASYN University Peshawar PhD Computer Science 18.01.2016 30.10.2017 Abbottabad University of Science & 12 Technology, Abbottabad MPhil Pharmacy Spring, 2021 17.08.2021 Abbottabad University of Science & 13 Technology, Abbottabad MS Management Science Fall, 2020 01.07.2021 Abbottabad University of Science & MPhil (Computer Science Fall 2020 01.02.2021 14 Technology, Abbottabad Abbottabad University of Science & 15 Technology, Abbottabad PhD in Physics Fall, 2020 17.09.2020 MS/M.Phil / Equivalent Sr. # University Program PhD Program With effect from Date of Issue Abbottabad University of Science & 16 Technology, Abbottabad