The Fall of Enron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Court of Appeals for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT Argued October 7, 2016 Decided December 27, 2016 No. 15-7121 ENRON NIGERIA POWER HOLDING, LTD., APPELLEE v. FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA, APPELLANT Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (No. 1:13-cv-01106) David Elesinmogun argued the cause and filed the briefs for appellant. Kenneth R. Barrett argued the cause and filed the briefs for appellee. Before: ROGERS, TATEL and GRIFFITH, Circuit Judges. Opinion for the Court filed by Circuit Judge ROGERS. ROGERS, Circuit Judge: In 1999, the Republic of Nigeria entered into a power purchase agreement (“PPA”) with Enron Nigeria Power Holding, Ltd. (“ENPH”), for construction of 2 electrical facilities. Days later, Nigeria suspended implementation of the PPA, and after years of attempted renegotiation over one phase of construction proved fruitless, ENPH filed under the PPA for arbitration by the International Chamber of Commerce’s International Court of Arbitration (“ICC”). The ICC issued an Award in ENPH’s favor. When collection efforts failed, ENPH filed a petition for confirmation and enforcement of the Award in the federal district court here. Nigeria now appeals from the order granting enforcement of the Award. Invoking Article V(2)(b) of The Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (known as the “New York Convention”), 21 U.S.T. 2517, Nigeria contends that enforcement of the Award violates the public policy of the United States not to reward a party for fraudulent and criminal conduct. It maintains that ENPH and Enron International Corporation (“Enron”) are alter egos, and, alternatively, that ENPH made false and fraudulent representations about Enron to induce Nigeria to enter the PPA. -

Enron's Pawns

Enron’s Pawns How Public Institutions Bankrolled Enron’s Globalization Game byJim Vallette and Daphne Wysham Sustainable Energy and Economy Network Institute for Policy Studies March 22, 2002 About SEEN The Sustainable Energy and Economy Network, a project of the Institute for Policy Studies (Washington, DC), works in partnership with citizens groups nationally and globally on environment, human rights and development issues with a particular focus on energy, climate change, environmental justice, and economic issues, particularly as these play out in North/South relations. SEEN views these issues as inextricably linked to global security, and therefore applies a human security paradigm as a framework for guiding its work. The reliance of rich countries on fossil fuels fosters a climate of insecurity, and a rationale for large military budgets in the North. In the South, it often fosters or nurtures autocratic or dictatorial regimes and corruption, while exacerbating poverty and destroying subsistence cultures and sustainable livelihoods. A continued rapid consumption of fossil fuels also ensures catastrophic environmental consequences: Climate change is a serious, emerging threat to the stability of the planet's ecosystems, and a particular hazard to the world's poorest peo- ple. The threat of climate change also brings more urgency to the need to reorient energy-related investments, using them to provide abundant, clean, safe energy for human needs and sustainable livelihoods. SEEN views energy not as an issue that can be examined in isolation, but rather as a vital resource embedded in a development strategy that must simultaneously address other fundamentals, such as education, health care, public par- ticipation in decision-making, and economic opportunities for the poorest. -

A Case of Corporate Deceit: the Enron Way / 18 (7) 3-38

NEGOTIUM Revista Científica Electrónica Ciencias Gerenciales / Scientific e-journal of Management Science PPX 200502ZU1950/ ISSN 1856-1810 / By Fundación Unamuno / Venezuela / REDALYC, LATINDEX, CLASE, REVENCIT, IN-COM UAB, SERBILUZ / IBT-CCG UNAM, DIALNET, DOAJ, www.jinfo.lub.lu.se Yokohama National University Library / www.scu.edu.au / Google Scholar www.blackboard.ccn.ac.uk / www.rzblx1.uni-regensburg.de / www.bib.umontreal.ca / [+++] Cita / Citation: Amol Gore, Guruprasad Murthy (2011) A CASE OF CORPORATE DECEIT: THE ENRON WAY /www.revistanegotium.org.ve 18 (7) 3-38 A CASE OF CORPORATE DECEIT: THE ENRON WAY EL CASO ENRON. Amol Gore (1) and Guruprasad Murthy (2) VN BRIMS Institute of Research and Management Studies, India Abstract This case documents the evolution of ‘fraud culture’ at Enron Corporation and vividly explicates the downfall of this giant organization that has become a synonym for corporate deceit. The objectives of this case are to illustrate the impact of culture on established, rational management control procedures and emphasize the importance of resolute moral leadership as a crucial qualification for board membership in corporations that shape the society and affect the lives of millions of people. The data collection for this case has included various sources such as key electronic databases as well as secondary data available in the public domain. The case is prepared as an academic or teaching purpose case study that can be utilized to demonstrate the manner in which corruption creeps into an ambitious organization and paralyses the proven management control systems. Since the topic of corporate practices and fraud management is inherently interdisciplinary, the case would benefit candidates of many courses including Operations Management, Strategic Management, Accounting, Business Ethics and Corporate Law. -

July 31, 2013 Local Government Assistance & Economic Analysis

July 31, 2013 Local Government Assistance & Economic Analysis Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts P.O. Box 13528 Austin, Texas 78711-3528 RE: Application to the Fort Stockton Independent School District from Barilla Solar, LLC FIRST QUALIFYING YEAR 2014 To the Local Government Assistance & Economic Analysis Division: By copy of this letter transmitting the application for review to the Comptroller’s Office, the Fort Stockton Independent School District is notifying the Applicant Barilla Solar, LLC of its intent to consider Barilla Solar, LLC’s application for appraised value limitation on qualified property. The Applicant submitted the application to the school district on July 22, 2013. The Board voted at a properly posted Board meeting to accept the application on July 22, 2013. The application was determined complete by the school district on July 31, 2013. Please prepare the economic impact report. The Applicant has included confidential materials with the application. The materials have been provided both in electronic and hard copy format. We have not attached the confidential materials to this email to avoid the unintended disclosure of these materials. Barilla Solar, LLC has also requested that Page 8 of the Application and Schedules A-D attached be kept “Confidential”, as well. Your office has already determined that information regarding investment levels and employment cannot be kept confidential. Even though the Applicant has written Confidential across the top of the Schedules, such information must be published on the website. Letter to Local Government Assistance & Economic Analysis Division July 31, 2013 Page 2 of 2 No construction has begun at the project site as of the date of the filing of the application and the District’s determination that the application is complete. -

EN RON CORP. NOTICE of ANNUAL MEETING of SHAREHOLDERS May 2, 2000

EN RON CORP. NOTICE OF ANNUAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS May 2, 2000 To THE S I-I AREHOLDERS: Notice is hereby given that the annual meeting of shareholders of Enton Corp. ("Enron") will be held in the LaSalle Ballroom of the Doubletree Hotel at Allen Center, 400 Dallas Street, Houston, Texas. at 10:00 a.m. Houston time on Tuesday, May 2, 2000, for the following purposes: I. To elect eighteen directors of Enron to hold office until the next annual meeting of shareholders and until their respective successors are duly elected and qualified; 2. To ratify the Board of Directors' appointment of Arthur Andersen LLP, independent public accountants, as Enton's auditors for the year ending December 31, 2000; 3. To consider a shareholder proposal from Brent Blackwelder, President, Friends of the Earth Action; 4. To consider a shareholder proposal from Dr. Julia M. Wershing; and 5. To transact such other business as may properly be brought before the meeting or any adjoumment(s) thereof. Holders of record of Enron Common Stock and Cumulative Second Preferred Convertible Stock at the close of business on March 3. 2000. will be entitled to notice of and to vote at the meeting or any adjoumment(s) thereof. Shareholders who do not expect to attend the meeting are requested to sign and return the enclosed proxy, for which a postage·paid, return envelope is enclosed. The proxy must be signed and returned in order to be counted. By Order of the Board of Directors, REBECCA C. CARTER Senior Vice President, Board Communications and Secretary Houston. -

The Financial Collapse of the Enron Corporation and Its Impact in the United States Capital Market by Prof

Global Journal of Management and Business Research: D Accounting and Auditing Volume 14 Issue 4 Version 1.0 Year 2014 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4588 & Print ISSN: 0975-5853 The Financial Collapse of the Enron Corporation and Its Impact in the United States Capital Market By Prof. Edel Lemus, M.I.B.A Carlos Albizu University, U nited States Abstract- The purpose of this article is to review the collapse of the Enron Corporation and the collapse’s effect on the United States financial market. Enron Corporation, the seventh largest company in the United States, misguided its shareholders by reporting $74 billion profit of which $43 billion was detected as fraud. Moreover, according to the association of fraud examiners $2.9 trillion was lost because of employee fraud. For example, as presented by Kieso, Weygandt, and Warfield (2013), in a global survey study that was conducted in 2013, it was reported that 3,000 executives from 54 countries were involved in fraudulent financial reporting. Therefore, the world of accounting is dominated by the top four accounting firms known as (1). PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), (2). Deloitte & Touche (DT), (3). Ernst & Young (EY) and (4). KPMG which represent a combined income of $80 billion. Keywords: enron corporation, bankruptcy, securities and exchange commission (sec), generally accepted accounting principles (gaap), sarbanes-oxley act of 2002, section 404, corporate governance, auditing, and economic crime. GJMBR-D Classification : JEL Code: M49 TheFinancialCollapseoftheEnronCorporationand Its ImpactintheUnitedStatesCapitalMarket Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2014. Prof. Edel Lemus. -

The Lesson from Enron Case - Moral and Managerial Responsibilities

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306091392 The Lesson from Enron Case - Moral and Managerial Responsibilities Article · August 2016 CITATION READS 1 27,811 1 author: Seied Beniamin Hosseini Aligarh Muslim University 29 PUBLICATIONS 26 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Strategies for Growth and Sustainability: A study of SMEs in India View project All content following this page was uploaded by Seied Beniamin Hosseini on 04 September 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 8, Issue, 08, pp.37451-37460, August, 2016 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE THE LESSON FROM ENRON CASE - MORAL AND MANAGERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES 1,*Seied Beniamin Hosseini and 2Dr. Mahesh, R. 1PG Student in MBA, B.N. Bahadur Institute of Management Sciences (BIMS), University of Mysore, Mysore Karnataka, India 2Associate Professor, B.N. Bahadur Institute of Management Sciences (BIMS), University of Mysore Mysore Karnataka, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: The Enron scandal, give out in October 2001, Enron Top officials abused their privileges and power, manipulated information put their own interests above those of their employees and the public and Received 19th May, 2016 Received in revised form failed to exercise proper oversight or shoulder responsibility for ethical failings which eventually led 15th June, 2016 to the bankruptcy of an American energy company based in Houston, Texas, and the dissolution of Accepted 17th July, 2016 Arthur Andersen, which was one of the five largest audit and accountancy partnerships in the world. -

How to Become a Scandal Adventures in Bad Behavior 1St Edition Download Free

HOW TO BECOME A SCANDAL ADVENTURES IN BAD BEHAVIOR 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Laura Kipnis | 9780312610579 | | | | | How to Become a Scandal: Adventures in Bad Behavior Enron filed for bankruptcy on December 2, Lawrence University St. Clearly, this is not an How to Become a Scandal Adventures in Bad Behavior 1st edition list, and I invite you all to add to it How to Become a Scandal Adventures in Bad Behavior 1st edition the comments section below or at hopematters4learning. Retrieved January 29, Societies have always purified themselves through shows of moral indignation, dumping their burdens off onto designated candidates- all the abnormality and moral disability that threatens to poison the community. I am a giant Laura Kipnis fan. But what it does investigate is the question, "What makes something a scandal? Community Reviews. Kipnis is a professor at Northwestern University. Why put your neck out on the chopping block when it's fairly likely to get cut off? Then you have more trouble on your hands than I know what to do with. Energy Intelligence Group, Inc. The low cost of natural gas and cheap labor supply during the Great Depression helped to fuel the company's early beginnings. Retrieved February 19, Texas portal Companies portal. Retrieved August 26, InEnron's Chief Operating Officer Jeffrey Skilling hired Andrew Fastowwho was well acquainted with the burgeoning deregulated energy market that Skilling wanted to exploit. Retrieved June 26, Once I accustomed myself to the author's self-consciously jazzy prose style, I settled in to thoroughly enjoy her dissection of four recent scandals. -

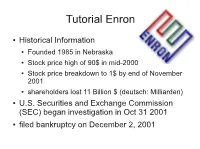

Tutorial Enron

Tutorial Enron ● Historical Information ● Founded 1985 in Nebraska ● Stock price high of 90$ in mid-2000 ● Stock price breakdown to 1$ by end of November 2001 ● shareholders lost 11 Billion $ (deutsch: Milliarden) ● U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) began investigation in Oct 31 2001 ● filed bankruptcy on December 2, 2001 Enron's success ● Thrive of Enron ● selling of electricity and gas ● through strong lobying by Enron a deregulation of prices was prevented ● Dec. 2000, market capitalization exceeded $60 billion, – 70 times earnings http://www.50statesclassifieds.com/uploadedi mages/4703312gas1.jpg – six times book value – an indication of the stock market’s high expectations about its future Management board ● CEOs ● Kenneth Lay, Founder, former Chairman and CEO (CEO 1985-2002) ● Jeffrey Skilling, former President, CEO (Dez. 2000- Aug 2001) and COO ● Rebecca Mark-Jusbasche, former Vice Chairman, Chairman and CEO of Enron International ● Stephen F. Cooper, Interim CEO and CRO ● Andrew Fastow, former CFO ● Auditing company ● Arthur Anderson (Auditing company) Time-Line ● 01.11.2000 Lay begins selling shares ● 12.02.2001 Skilling is named CEO ● 21.06.2001 Skilling is hit in the face with a pie ● 14.08.2001 Skilling resigns ● 16.08.2001 Lay discusses Skilling's departure ● 21.08.2001 Lay states that increasing stock price has one of the highest priority ● 16.09.2001 Lay to employees: “the third quarter is looking great” ● www.fact-index.com/t/ti/timeline_of_the_enron_scandal.html Outrages (Excerpt) ● Kenneth Lay ● Spread of -

Enron Annual Report 2000

Enron Annual Report Enron 2000 Enron Annual Report 2000 Enron manages efficient, flexible networks to reliably deliver physical products at predictable prices. In 2000 Enron used its networks to deliver a record amount of physical natural gas, electricity, bandwidth capacity and other products. With our networks, we can significantly expand our existing businesses while extending our services to new markets with enormous potential for growth. CONTENTS 1 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 20 FINANCIAL REVIEW 2 LETTER TO SHAREHOLDERS 53 OUR VALUES 9 ENRON WHOLESALE SERVICES 54 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 14 ENRON ENERGY SERVICES 56 ENRON CORPORATE POLICY COMMITTEE 16 ENRON BROADBAND SERVICES 56 SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION 18 ENRON TRANSPORTATION SERVICES FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (Unaudited: in millions, except per share data) 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 Revenues $100,789 $ 40,112 $ 31,260 $ 20,273 $13,289 Net income: Operating results $ 1,266 957 698 515 493 Items impacting comparability (287) (64) 5 (410) 91 Total $ 979 893 703 105 584 Earnings per diluted common share: Operating results $ 1.47 1.18 1.00 0.87 0.91 Items impacting comparability (0.35) (0.08) 0.01 (0.71) 0.17 Total $ 1.12 1.10 1.01 0.16 1.08 Dividends paid per common share $ 0.50 0.50 0.48 0.46 0.43 Total assets $ 65,503 33,381 29,350 22,552 16,137 Cash from operating activities (excluding working capital) $ 3,010 2,228 1,873 276 742 Capital expenditures and equity investments $ 3,314 3,085 3,564 2,092 1,483 NYSE price range 9 7 3 9 3 High $ 90 ⁄16 44 ⁄8 29 ⁄8 22 ⁄16 23 ⁄4 3 3 1 1 5 Low 41 ⁄8 28 ⁄4 19 ⁄16 -

First Consolidated and Amended Complaint in The

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION PAMELA M. TITTLE; THOMAS O. PADGETT; FIRST CONSOLIDATED AND AMENDED GARY S. DREADIN; JANICE FARMER; COMPLAINT LINDA BRYAN; JOHN L. MOORE; BETTY J. CLARK; SHELLY FARIAS; PATRICK CIVIL ACTION NO. H 01-3913 CAMPBELL; FANETTE PERRY; CHARLES AND CONSOLIDATED CASES PRESTWOOD; ROY RINARD; STEVE LACEY; CATHERINE STEVENS; ROGER W. BOYCE; WAYNE M. STEVENS; NORMAN L. and PAULA H. YOUNG; MICHAEL L. MCCOWN; DAN SHULTZ, on behalf of themselves and a class of persons similarly situated, and on behalf of the Enron Corp Savings Plan, the Enron Corp Employee Stock Ownership Plan and the Enron Corp. Cash Balance Plan, Plaintiffs, v. ENRON CORP., an Oregon corporation; ENRON CORP. SAVINGS PLAN ADMINISTRATIVE COMMITTEE; ENRON EMPLOYEE STOCK OWNERSHIP PLAN ADMINISTRATIVE COMMITTEE; CINDY K. OLSON; MIKIE RATH; JAMES S. PRENTICE; MARY K. JOYCE; SHEILA KNUDSEN; ROD HAYSLETT; PAULA RIEKER; WILLIAM D. GATHMANN; TOD A. LINDHOLM; PHILIP J. BAZELIDES; JAMES G. BARNHART; KEITH CRANE; WILLIAM J. GULYASSY; DAVID SHIELDS; JOHN DOES NOS. 1-100 UNKNOWN FIDUCIARIES OF THE ENRON CORP SAVINGS PLAN OR THE ESOP; THE NORTHERN TRUST COMPANY; KENNETH L. LAY; JEFFREY K. SKILLING; ANDREW S. FASTOW; MICHAEL KOPPER; RICHARD A. CAUSEY; JAMES V. DERRICK, JR.; THE ESTATE OF J. CLIFFORD BAXTER; MARK A. FREVERT; STANLEY C. HORTON; FIRST CONSOLIDATED AND AMENDED COMPLAINT 1544.10 0114 BSC.DOC KENNETH D. RICE; RICHARD B. BUY; LOU L. PAI; ROBERT A. BELFER; NORMAN P. BLAKE, JR.; RONNIE C. CHAN; JOHN H. DUNCAN; WENDY L. GRAMM; ROBERT K. JAEDICKE; CHARLES A. LEMAISTRE; JOE H. -

Research Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 8, Issue, 08, pp.37451-37460, August, 2016 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE THE LESSON FROM ENRON CASE - MORAL AND MANAGERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES 1,*Seied Beniamin Hosseini and 2Dr. Mahesh, R. 1PG Student in MBA, B.N. Bahadur Institute of Management Sciences (BIMS), University of Mysore, Mysore Karnataka, India 2Associate Professor, B.N. Bahadur Institute of Management Sciences (BIMS), University of Mysore Mysore Karnataka, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: The Enron scandal, give out in October 2001, Enron Top officials abused their privileges and power, manipulated information put their own interests above those of their employees and the public and Received 19th May, 2016 Received in revised form failed to exercise proper oversight or shoulder responsibility for ethical failings which eventually led 15th June, 2016 to the bankruptcy of an American energy company based in Houston, Texas, and the dissolution of Accepted 17th July, 2016 Arthur Andersen, which was one of the five largest audit and accountancy partnerships in the world. Published online 31st August, 2016 In addition to being the largest bankruptcy reorganization in American history at that time, Enron undoubtedly is the biggest audit failure. It is one of companies which fell down too fast. This paper Key words: will analyze the reason for this event in detail including the management, conflict of interest and Enron, Management Control System, accounting fraud. Meanwhile, it will make analysis the moral responsibility From Individuals’ Angle Fraud, Sarbanes, Corporate Leadership. and Corporation’s Angle.