What If Heidegger Used Fountain Instead of Van Gogh&

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

AMELIA JONES “'Women' in Dada: Elsa, Rrose, and Charlie”

AMELIA JONES “’Women’ in Dada: Elsa, Rrose, and Charlie” From Naomi Sawelson-Gorse, Women in Dada:Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998): 142-172 In his 1918 Dada manifesto, Tristan Tzara stated the sources of “Dadaist Disgust”: “Morality is an injection of chocolate into the veins of all men....I proclaim the opposition of all cosmic faculties to [sentimentality,] this gonorrhea of a putrid sun issued from the factories of philosophical thought.... Every product of disgust capable of becoming a negation of the family is Dada.”1 The dadaists were antagonistic toward what they perceived as the loss of European cultural vitality (through the “putrid sun” of sentimentality in prewar art and thought) and the hypocritical bourgeois morality and family values that had supported the nationalism culminating in World War I.2 Conversely, in Hugo Ball's words, Dada “drives toward the in- dwelling, all-connecting life nerve,” reconnecting art with the class and national conflicts informing life in the world.”3 Dada thus performed itself as radically challenging the apoliticism of European modernism as well as the debased, sentimentalized culture of the bourgeoisie through the destruction of the boundaries separating the aesthetic from life itself. But Dada has paradoxically been historicized and institutionalized as “art,” even while it has also been privileged for its attempt to explode the nineteenth-century romanticism of Charles Baudelaire's “art for art's sake.”4 Moving against the grain of most art historical accounts of Dada, which tend to focus on and fetishize the objects produced by those associated with Dada, 5 I explore here what I call the performativity of Dada: its opening up of artistic production to the vicissitudes of reception such that the process of making meaning is itself marked as a political-and, specifically, gendered-act. -

Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection... Page 1 of 26 Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection IRENE E. HOFMANN Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago Dada 6 (Bulletin The Mary Reynolds Collection, which entered The Art Institute of Dada), Chicago in 1951, contains, in addition to a rich array of books, art, and ed. Tristan Tzara ESSAYS (Paris, February her own extraordinary bindings, a remarkable group of periodicals and 1920), cover. journals. As a member of so many of the artistic and literary circles View Works of Art Book Bindings by publishing periodicals, Reynolds was in a position to receive many Mary Reynolds journals during her life in Paris. The collection in the Art Institute Finding Aid/ includes over four hundred issues, with many complete runs of journals Search Collection represented. From architectural journals to radical literary reviews, this Related Websites selection of periodicals constitutes a revealing document of European Art Institute of artistic and literary life in the years spanning the two world wars. Chicago Home In the early part of the twentieth century, literary and artistic reviews were the primary means by which the creative community exchanged ideas and remained in communication. The journal was a vehicle for promoting emerging styles, establishing new theories, and creating a context for understanding new visual forms. These reviews played a pivotal role in forming the spirit and identity of movements such as Dada and Surrealism and served to spread their messages throughout Europe and the United States. -

The Alterity of the Readymade: Fountain and Displaced Artists in Wartime

THE ENDURING IMPACT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR A collection of perspectives Edited by Gail Romano and Kingsley Baird The Alterity of the Readymade: Fountain and Displaced Artists in Wartime Marcus Moore Massey University Abstract In April 1917, a porcelain urinal titled Fountain was submitted by Marcel Duchamp (or by his female friend, Louise Norton) under the pseudonym ‘R. MUTT’, to the Society of Independent Artists in New York. The Society’s committee refused to show it in their annual exhibition of some 2,125 works held at the Grand Central Palace. Eighty-seven years later, in 2004, Fountain was voted the most influential work of art in the 20th century by a panel of world experts. We inherit the 1917 work not because the original object survived—it was thrown out into the rubbish—but through a photographic image that Alfred Steiglitz was commissioned to take. In this photo, Marsden Hartley’s The Warriors, painted in 1913 in Berlin, also appears, enlisted as the backdrop for the piece of American hardware Duchamp selected from a plumbing showroom. To highlight the era of the Great War and its effects of displacement on individuals, this article considers each subject in turn: Marcel Duchamp’s departure from Paris and arrival in New York in 1915, and Marsden Hartley’s return to New York in 1915 after two years immersing himself in the gay subculture in pre-war Berlin. As much as describe the artists’ experiences of wartime, explain the origin of the readymade and reconstruct the events of the notorious example, Fountain, the aim of this article is to additionally bring to the fore the alterity of the other item imported ready-made in the photographic construction—the painting The Warriors. -

Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp/ the Mary Sisler collection/ 78 works 1904-1963 sponsored by the Queen Elizabeth SecondArts Council of NewZealand gG<- Auckland [Wellington jChristchurch Acknowledgements It is inadvisable to shoot in the dark — but it sometimes seems to bring results I We are glad it did in this case. A letter to Cordier 6r Ekstrom Gallery, New York, in September 1965, where a Marcel Duchamp retrospective exhibition had just been presented, triggered a chain of events leading to the landing of a Marcel Duchamp exhibition in Auckland in April 1967, to commence a New Zealand tour —then to Australia and possibly Japan. We would like to thank Mrs Mary Sisler of New York who has generously made her collection available; Mr Alan Solomon, Director, The Exhibition of American Art at Montreal; The Arts Council of Great Britain, from whose comprehensive catalogue 'The almost complete works of Marcel Duchamp' the present catalogue has been compiled and who kindly supplied photographs for reproduction; The Queen Elizabeth II The Second Arts Council of New Zealand under whose sponsorship the exhibition is being toured in New Zealand. G. C. Docking City of Auckland Art Gallery April 1967 Marcel Duchamp 1887 Born 28 July near Blainville, France. Duchamp's grandfather was a painter; his elder brothers, Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, and younger sister, Suzanne, became artists 1902 Begins painting. Landscape at Blainville known as his first work (not included in the exhibition). 1904 Graduates from the Ecole Bossuet, the lycee in Rouen. Joins his elder brothers in Paris, where he studies painting at the Academie Julian until July 1905. -

Florine Stettheimer: a Re-Appraisal of the Artist in Context

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1994 Florine Stettheimer: a Re-Appraisal of the Artist in Context Melissa (Liles) Parris Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Modern Art and Architecture Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4118 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPROVAL CERTIFICATE FLORINE STETTHEIMER: A Re-Appraisal of the Artist in Context by Melissa M. Liles Approved: Thesis Reader · Chait:-, 6hiduate Committee---> FLORJNE STETTHEIMER: A Re-Appraisal of the Artist in Context by Melissa M. Liles B.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 1991 Submitted to the Faculty of the School of the Arts of Virginia Commonwealth University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Master of Arts Richmond, Virginia May 1994 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Gail Y. Liles (1936-1993), whose free spirit, loving support, and unremitting encouragement was a constant source of inspiration. For this, I am eternally grateful. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .. ... .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. v Foreword ................................................................................................................ -

November/Dec Galley 4/9/15 16:59 Page 1

Duchamp and the Fountain:November/Dec galley 4/9/15 16:59 Page 1 THE JACKDAW WHO DID IT? NOT DUCHAMP! Duchamp and the Fountain:November/Dec galley 4/9/15 16:59 Page 2 2 A CONCEPTUAL INCONVENIENCE Former museum director Julian Spalding and academic Glyn Thompson published an important article in The Art Newspaper in November 2014 (available online at the paper’s website and also in a longer version on the Scottish Review of Books website) proposing that the object we know as Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain , the urinal, was in fact the work of someone else: dadaist artist and poet Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. The original Fountain was famously lost. In 1999 the Tate bought a 1964 copy for $500,000: it is one of 16 replicas made between 1951 and 1964. In 2004 ‘art experts’ declared Fountain the most influential work of art of the 20th century. Spalding and Thompson have asked for Fountain to be reattributed to its true author. What follows is a correspondence between the authors and Sir Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate Gallery. An exhibition, ‘A Lady’s not a Gent’s’, about the history of Fountain will take place at Summerhall, 1 Summerhall, during the Edinburgh Festival from August 5th to October 5th. www.summerhall.co.uk Duchamp and the Fountain:November/Dec galley 4/9/15 16:59 Page 3 3 November 10th, 2014 consultation must be in the public domain. Dear Nick, We would, therefore, be grateful if you A call to reattribute Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain would supply us with a list of these specialists and a summary of the cases e write following our argument made in the November issue of they have made. -

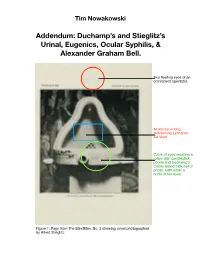

Addendum- Duchamp's and Stieglitz's Urinal, Eugenics, Ocular Syphilis

Tim Nowakowski Addendum: Duchamp’s and Stieglitz’s Urinal, Eugenics, Ocular Syphilis, & Alexander Graham Bell. Two floating eyes of an omniscient spectator. Mirrorical writing referencing Leonardo Da Vinci. Circle of eyes recalling a rotary dial candlestick phone and Duchamp’s Coney Island trick mirror photo, both entail a circle of ten eyes. Figure 1. Page from The BlindMan, No. 2 showing urinal photographed by Alfred Stieglitz. Figure 2. Derivative graphics from The Blind Man, No. 2, copyright by Tim Nowakowski, illustrating the circle of 10 ‘eyes’ bleeding through from the other side of the page, composing in effect a simulation of a candlestick rotary dial phone. Figure 3. Figure 4. Unknown photographer, 5-way portrait of Duchamp. Duchamp having a Spiritualist seance with himself(s), the foreground figure showing the back of his head anticipating the back turned head in Tonsure as well as the Apple-bowl Billiard style smoking pipe. This vaguely compares to the cluster of bachelors in the LG. Divining the presence of eugenics within Marcel Duchamp/Alfred Stieglitz’s Fountain, The BlindMan, No.2, and Rongwrong, reveals some problems in Duchampian scholarship. Traveling from England via a stay with Mable Dodge in Florence, writer/ poet/painter of lampshades Mina Loy, well represented in both Blind Man editions, wrote works which led critics of British literature to characterize her as the eugenics madonna or ‘race mother’. (See this author’s Marcel Duchamp: Eugenics, Race Suicide, dénatalité, State Selective Breeding, Mina Loy, R. Mutt, Roosevelt Mutt and Rongwrong Mutt). Duchamp’s ‘race suicide’ comment here and mandatory government-sponsored natalism suggested in the McBride article, mentioned previously, perplexingly yields no such discourse on race degeneracy among scholars of Duchamp. -

Journalof the ARTS in SOCIETY

The International JOURNALof the ARTS IN SOCIETY Volume 3, Number 5 Fountain Mediated: Marcel Duchamp’s Artwork and its Adapting Material Content Yannis Zavoleas www.arts-journal.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN SOCIETY http://www.arts-journal.com First published in 2009 in Melbourne, Australia by Common Ground Publishing Pty Ltd www.CommonGroundPublishing.com. © 2009 (individual papers), the author(s) © 2009 (selection and editorial matter) Common Ground Authors are responsible for the accuracy of citations, quotations, diagrams, tables and maps. All rights reserved. Apart from fair use for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act (Australia), no part of this work may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please contact <[email protected]>. ISSN: 1833-1866 Publisher Site: http://www.Arts-Journal.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN SOCIETY is peer-reviewed, supported by rigorous processes of criterion-referenced article ranking and qualitative commentary, ensuring that only intellectual work of the greatest substance and highest significance is published. Typeset in Common Ground Markup Language using CGCreator multichannel typesetting system http://www.commongroundpublishing.com/software/ Fountain Mediated: Marcel Duchamp’s Artwork and its Adapting Material Content Yannis Zavoleas, University of Patras, Greece Abstract: The paper draws upon the relationship between artistic documentation and content over Marcel Duchamp’s sculpture work Fountain. The original Fountain was lost soon after it was created in 1917. Since then, Fountain has been reproduced in various media formats, such as photographs, descriptions and replicas. It may be argued that the mediated Fountains were treated as artworks of their own, meanwhile holding and aiding to increase the artistic aura of the original. -

Les Nouvelles Fables De Fountain 1917-2017 Michaël La Chance

Document generated on 09/30/2021 11:35 a.m. Inter Art actuel Les nouvelles fables de Fountain 1917-2017 Michaël La Chance Number 127, Supplement, Fall 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/86333ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Les Éditions Intervention ISSN 0825-8708 (print) 1923-2764 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article La Chance, M. (2017). Les nouvelles fables de Fountain 1917-2017. Inter, (127), 1–74. Tous droits réservés © Les Éditions Intervention, 2017 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ LES NOUVELLES FABLES DE 1917-2017 CHRONOLOGIE ÉTABLIE PAR MICHAËL LA CHANCE ANNOTATIONS D’ANDRÉ GERVAIS Table des fables I Fable du géniteur 11 II Fable de Mott 16 III Fable des sœurs 18 IV Fable de la baronne 21 V Fable des besoins sublimés 23 VI Fable de la disparition : la porcelaine brisée 26 VII Fable de la disparition : l’œuvre n’a jamais existé 26 VIII Fable du cheval de Troie 28 IX Fable de la compétition statutaire et de l’exclusion de caste 29 X Fable de la Dame Voyou 30 XI Fable des sanitaires substitués 31 XII Fable mutique 34 XIII Fable de l’œuvre escamotée 38 XIV Fable XYZW [par André Gervais] 39 XV Fable du triomphe de l’abject devant un public médusé 40 XVI Fable de l’œuvre autoengendrée 41 XVII Fable PtBtT 42 XVIII Fable des muses 44 XIX Fable des fantômes 53 XX Fable du pendu femelle 61 XXI Fable du marché aux puces 62 Marcel Duchamp, Pasadena Art Museum, Los Angeles, 1963. -

MARCEL DUCHAMP's Fountain

The International JOURNALof the ARTS IN SOCIETY Volume 3, Number 5 Fountain Mediated: Marcel Duchamp’s Artwork and its Adapting Material Content Yannis Zavoleas www.arts-journal.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN SOCIETY http://www.arts-journal.com First published in 2009 in Melbourne, Australia by Common Ground Publishing Pty Ltd www.CommonGroundPublishing.com. © 2009 (individual papers), the author(s) © 2009 (selection and editorial matter) Common Ground Authors are responsible for the accuracy of citations, quotations, diagrams, tables and maps. All rights reserved. Apart from fair use for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act (Australia), no part of this work may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please contact <[email protected]>. ISSN: 1833-1866 Publisher Site: http://www.Arts-Journal.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN SOCIETY is peer-reviewed, supported by rigorous processes of criterion-referenced article ranking and qualitative commentary, ensuring that only intellectual work of the greatest substance and highest significance is published. Typeset in Common Ground Markup Language using CGCreator multichannel typesetting system http://www.commongroundpublishing.com/software/ Fountain Mediated: Marcel Duchamp’s Artwork and its Adapting Material Content Yannis Zavoleas, University of Patras, Greece Abstract: The paper draws upon the relationship between artistic documentation and content over Marcel Duchamp’s sculpture work Fountain. The original Fountain was lost soon after it was created in 1917. Since then, Fountain has been reproduced in various media formats, such as photographs, descriptions and replicas. It may be argued that the mediated Fountains were treated as artworks of their own, meanwhile holding and aiding to increase the artistic aura of the original. -

Rarities from 1917: Facsimiles of <I>The Blind Man No.1

Rarities from 1917: Facsimiles of The Blind Man No.1, The Blind Man No.2 and Rongwrong A few years after his arrival in the United States, Marcel Duchamp, together with his friends Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood, published three small and very short-lived issues of what can only be described as genuine Dada-journals: The Blind Man No.1 (April 1917; Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, vol. 2, New York: Delano Greenidge, 1997, # 346), The Blind Man No. 2 (May 1917; # 347) and Rongwrong (July 1917; #348). Of the three, the Blind Man No. 2 is best remembered for publishing documents surrounding the scandal of Duchamp’s 1917 urinal Fountain. But the other numbers also hold an abundance of material on the budding, European-infiltrated and subversive New York art scene. Without further ado, dear reader, please see for yourself! Only once before, in 1970, were print-facsimiles of the three magazines made. Published in a small edition by Arturo Schwarz (Documenti Dada e Surrealisti, Archivi d’Arte del XX Secolo, Rome; editor: Gabriele Mazzotta, Milan) in a brown cardboard folder whose design imitates wood,Dada Americano also includes reprints of Duchamp’s and Man Ray’s one and only issue of New York Dada (April, 1921) as well as the latter’s four-page foldout of theRidgefield Gazook (No. 0, March 31st, 1915). The following clickable flip-through visuals of all pages of both issues of the Blind Man as well as Rongwrong are scans from the 1970 Schwarz edition and make their full content available to a large audience for the first time.