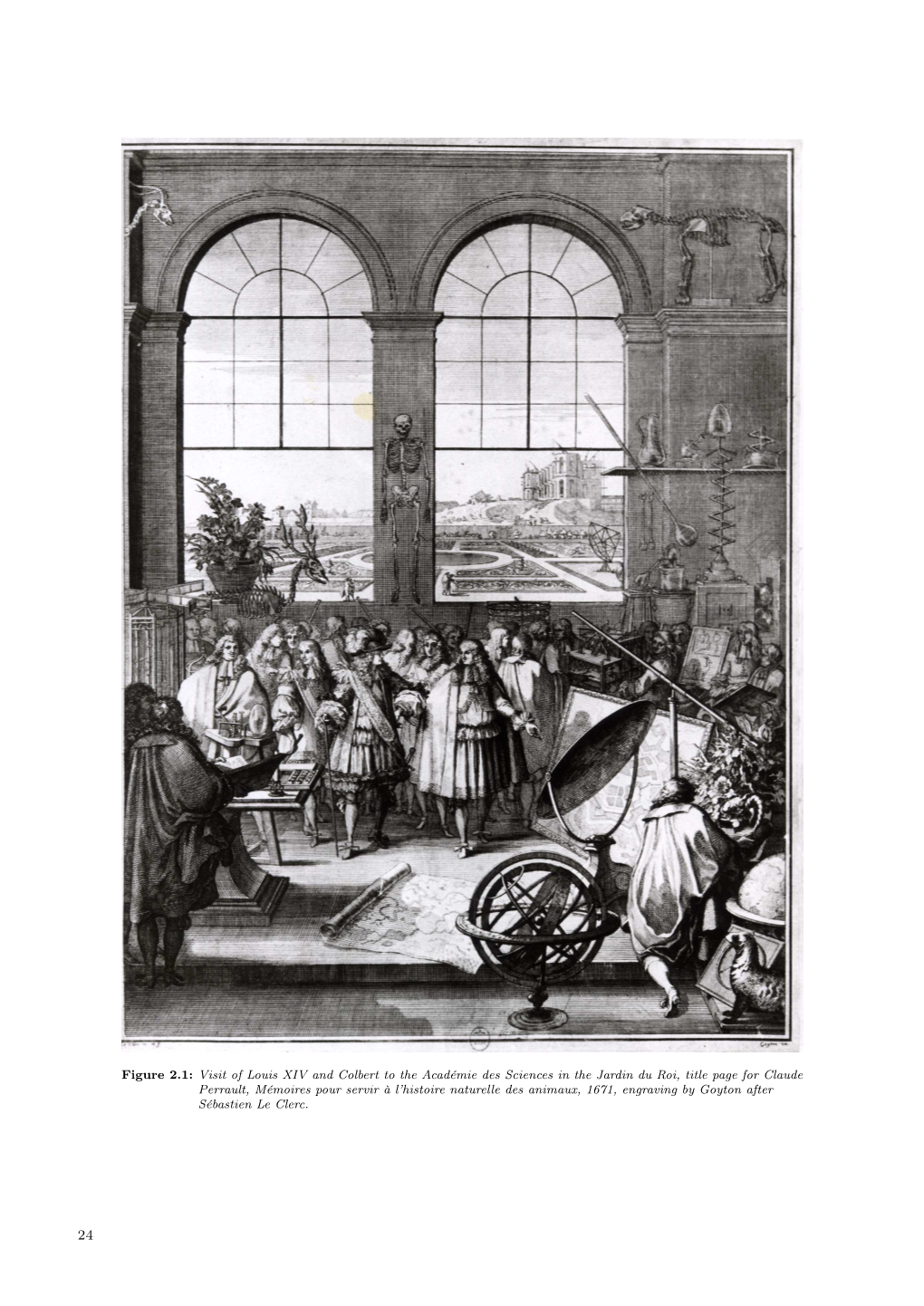

Visit of Louis XIV and Colbert to the Académie Des Sciences in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geodesy Methods Over Time

Geodesy methods over time GISC3325 - Lecture 4 Astronomic Latitude/Longitude • Given knowledge of the positions of an astronomic body e.g. Sun or Polaris and our time we can determine our location in terms of astronomic latitude and longitude. US Meridian Triangulation This map shows the first project undertaken by the founding Superintendent of the Survey of the Coast Ferdinand Hassler. Triangulation • Method of indirect measurement. • Angles measured at all nodes. • Scaled provided by one or more precisely measured base lines. • First attributed to Gemma Frisius in the 16th century in the Netherlands. Early surveying instruments Left is a Quadrant for angle measurements, below is how baseline lengths were measured. A non-spherical Earth • Willebrod Snell van Royen (Snellius) did the first triangulation project for the purpose of determining the radius of the earth from measurement of a meridian arc. • Snellius was also credited with the law of refraction and incidence in optics. • He also devised the solution of the resection problem. At point P observations are made to known points A, B and C. We solve for P. Jean Picard’s Meridian Arc • Measured meridian arc through Paris between Malvoisine and Amiens using triangulation network. • First to use a telescope with cross hairs as part of the quadrant. • Value obtained used by Newton to verify his law of gravitation. Ellipsoid Earth Model • On an expedition J.D. Cassini discovered that a one-second pendulum regulated at Paris needed to be shortened to regain a one-second oscillation. • Pendulum measurements are effected by gravity! Newton • Newton used measurements of Picard and Halley and the laws of gravitation to postulate a rotational ellipsoid as the equilibrium figure for a homogeneous, fluid, rotating Earth. -

OF Versailles

THE CHÂTEAU DE VErSAILLES PrESENTS science & CUrIOSITIES AT THE COUrT OF versailles AN EXHIBITION FrOM 26 OCTOBEr 2010 TO 27 FEBrUArY 2011 3 Science and Curiosities at the Court of Versailles CONTENTS IT HAPPENED AT VErSAILLES... 5 FOrEWOrD BY JEAN-JACqUES AILLAGON 7 FOrEWOrD BY BÉATrIX SAULE 9 PrESS rELEASE 11 PArT I 1 THE EXHIBITION - Floor plan 3 - Th e exhibition route by Béatrix Saule 5 - Th e exhibition’s design 21 - Multimedia in the exhibition 22 PArT II 1 ArOUND THE EXHIBITION - Online: an Internet site, and TV web, a teachers’ blog platform 3 - Publications 4 - Educational activities 10 - Symposium 12 PArT III 1 THE EXHIBITION’S PArTNErS - Sponsors 3 - Th e royal foundations’ institutional heirs 7 - Partners 14 APPENDICES 1 USEFUL INFOrMATION 3 ILLUSTrATIONS AND AUDIOVISUAL rESOUrCES 5 5 Science and Curiosities at the Court of Versailles IT HAPPENED AT VErSAILLES... DISSECTION OF AN Since then he has had a glass globe made that ELEPHANT WITH LOUIS XIV is moved by a big heated wheel warmed by holding IN ATTENDANCE the said globe in his hand... He performed several experiments, all of which were successful, before Th e dissection took place at Versailles in January conducting one in the big gallery here... it was 1681 aft er the death of an elephant from highly successful and very easy to feel... we held the Congo that the king of Portugal had given hands on the parquet fl oor, just having to make Louis XIV as a gift : “Th e Academy was ordered sure our clothes did not touch each other.” to dissect an elephant from the Versailles Mémoires du duc de Luynes Menagerie that had died; Mr. -

DR. DOMINIQUE AUBERT DOB 10Th August 1978 - 31 Years French

DR. DOMINIQUE AUBERT DOB 10th August 1978 - 31 years French Lecturer Université de Strasbourg Observatoire Astronomique [email protected] http://astro.u-strasbg.fr/~aubert CURRENT SITUATION Lecturer at the University of Strasbourg, member of the Astronomical Observatory since September 2006. TOPICS RESEARCH • Formation of large structures in the Universe, Cosmology • Epoch of Reionization, galaxies, galactic dynamics, gravitational lenses • Numerical simulations, high performance computing, hardware acceleration of scientific computing on graphics cards (Graphics Processing Units - GPUs) CAREER • October 2005 - September 2006: Post-Doc CNRS, Service d'Astrophysique, CEA, Saclay, France. • April 2005 - October 2005: Max-Planck Institut fur Astrophysik, Garching, Germany, visitor. • April 2004-October 2004: Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, UK, Marie Curie visitorship. • October 2001-April 2005: PhD thesis "Measurement and implications of dark matter flows at the surface of the virial sphere", University Paris XI and Astronomical Observatory of Strasbourg. REFEERED PUBLICATIONS • Reionisation powered by GPUs I : the structure of the ultra-violet background, Aubert D. & Teyssier R., April 2010, submitted to ApJ, available on request, arXiv:1004.2503 • The dusty, albeit ultraviolet bright infancy of galaxies. Devriendt, J.; Rimes, C.; Pichon, C.; Teyssier, R.; Le Borgne, D.; Aubert, D.; Audit, E.; Colombi, S.; Courty, S; Dubois, Y.; Prunet, S.; Rasera, Y.; Slyz, A.; Tweed, D., Submitted to MNRAS, arXiv:0912.0376 • Galactic kinematics with modified Newtonian dynamics. Bienaymé, O.; Famaey, B.; Wu, X.; Zhao, H. S.; Aubert, D. A&A, April 2009, in press. • A particle-mesh integrator for galactic dynamics powered by GPGPUs. Aubert, D., Amini, M. & David, R. Accepted contribution to ICCS 2009. • Full-Sky Weak Lensing Simulation with 70 Billion Particles. -

Measuring the Universe: a Brief History of Time

Measuring the Universe A Brief History of Time & Distance from Summer Solstice to the Big Bang Michael W. Masters Outline • Seasons and Calendars • Greece Invents Astronomy Part I • Navigation and Timekeeping • Measuring the Solar System Part II • The Expanding Universe Nov 2010 Measuring the Universe 2 Origins of Astronomy • Astronomy is the oldest natural science – Early cultures identified celestial events with spirits • Over time, humans began to correlate events in the sky with phenomena on earth – Phases of the Moon and cycles of the Sun & stars • Stone Age cave paintings show Moon phases! – Related sky events to weather patterns, seasons and tides • Neolithic humans began to grow crops (8000-5500 BC) – Agriculture made timing the seasons vital – Artifacts were built to fix the dates of the Vernal Equinox and the Summer Solstice A 16,500 year old night • Astronomy’s originators sky map has been found include early Chinese, on the walls of the famous Lascaux painted Babylonians, Greeks, caves in central France. Egyptians, Indians, and The map shows three bright stars known today Mesoamericans as the Summer Triangle. Source: http://ephemeris.com/history/prehistoric.html Nov 2010 Measuring the Universe 3 Astronomy in Early History • Sky surveys were developed as long ago as 3000 BC – The Chinese & Babylonians and the Greek astronomer, Meton of Athens (632 BC), discovered that eclipses follow an 18.61-year cycle, now known as the Metonic cycle – First known written star catalog was developed by Gan De in China in 4 th Century BC – Chinese -

Innovation and Sustainability in French Fashion Tech Outlook and Opportunities. Report By

Innovation and sustainability in French Fashion Tech outlook and opportunities Commissioned by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency and the Innovation Department of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in France December 2019 This study is commissioned by the Innovation Department of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in France and the Netherlands Enterprise Agency (RVO.nl). Written by Alice Gras and Claire Eliot Translated by Sophie Bramel pages 6-8 INTRODUCTION 7 01. Definition and key dates 8 02. Dutch fashion tech dynamics I 9-17 THE CONVERGENCE OF ECOLOGICAL AND ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY IN FASHION 11-13 01. Key players 14 02. Monitoring impact 14-16 03. Sustainable innovation and business models 17 04. The impact and long-term influence of SDGs II 18-30 THE FRENCH FASHION INNOVATION LANDSCAPE 22-23 01. Technological innovation at leading French fashion companies 25-26 02. Public institutions and federations 27-28 03. Funding programmes 29 04. Independent structures, associations and start-ups 30 05. Specialised trade events 30 06. Specialised media 30 07. Business networks 30 08 . Technological platforms III 31-44 FASHION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH: CURRENT AND FUTURE OUTLOOK 34-35 01. Mapping of research projects 36-37 02. State of fashion research in France 38-39 03. Key fields of research in fashion technology and sustainability 40 04. Application domains of textile research projects 42-44 05. Fostering research in France IV 45-58 NEW TECHNOLOGIES TO INNOVATE IN THE FRENCH FASHION SECTOR 47 01. 3D printing 48 02. 3D and CAD Design 49-50 03. Immersive technologies 51 04. -

ALBERT VAN HELDEN + HUYGENS’S RING CASSINI’S DIVISION O & O SATURN’S CHILDREN

_ ALBERT VAN HELDEN + HUYGENS’S RING CASSINI’S DIVISION o & o SATURN’S CHILDREN )0g-_ DIBNER LIBRARY LECTURE , HUYGENS’S RING, CASSINI’S DIVISION & SATURN’S CHILDREN c !@ _+++++++++ l ++++++++++ _) _) _) _) _)HUYGENS’S RING, _)CASSINI’S DIVISION _) _)& _)SATURN’S CHILDREN _) _) _)DDDDD _) _) _)Albert van Helden _) _) _) , _) _) _)_ _) _) _) _) _) · _) _) _) ; {(((((((((QW(((((((((} , 20013–7012 Text Copyright ©2006 Albert van Helden. All rights reserved. A H is Professor Emeritus at Rice University and the Univer- HUYGENS’S RING, CASSINI’S DIVISION sity of Utrecht, Netherlands, where he resides and teaches on a regular basis. He received his B.S and M.S. from Stevens Institute of Technology, M.A. from the AND SATURN’S CHILDREN University of Michigan and Ph.D. from Imperial College, University of London. Van Helden is a renowned author who has published respected books and arti- cles about the history of science, including the translation of Galileo’s “Sidereus Nuncius” into English. He has numerous periodical contributions to his credit and has served on the editorial boards of Air and Space, 1990-present; Journal for the History of Astronomy, 1988-present; Isis, 1989–1994; and Tractrix, 1989–1995. During his tenure at Rice University (1970–2001), van Helden was instrumental in establishing the “Galileo Project,”a Web-based source of information on the life and work of Galileo Galilei and the science of his time. A native of the Netherlands, Professor van Helden returned to his homeland in 2001 to join the faculty of Utrecht University. -

PDF Program Book

46th Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences with Historical Astronomy Division (HAD) 9-14 November 2014 | Tucson, AZ OFFICERS AND MEMBERS ........ 2 SPONSORS ............................... 2 EXHIBITORS .............................. 3 FLOOR PLANS ........................... 5 ATTENDEE SERVICES ................. 8 Session Numbering Key SCHEDULE AT-A-GLANCE ........ 10 100s Monday 200s Tuesday SUNDAY ................................. 20 300s Wednesday 400s Thursday MONDAY ................................ 23 500s Friday TUESDAY ................................ 44 Sessions are numbered in the program book by day and time. WEDNESDAY .......................... 75 All posters will be on display Monday - Friday THURSDAY.............................. 85 FRIDAY ................................. 119 Changes after 1 October are included only in the online program materials. AUTHORS INDEX .................. 137 1 DPS OFFICERS AND MEMBERS Current DPS Officers Heidi Hammel Chair Bonnie Buratti Vice-Chair Athena Coustenis Secretary Andrew Rivkin Treasurer Nick Schneider Education and Public Outreach Officer Vishnu Reddy Press Officer Current DPS Committee Members Rosaly Lopes Term Expires November 2014 Robert Pappalardo Term Expires November 2014 Ralph McNutt Term Expires November 2014 Ross Beyer Term Expires November 2015 Paul Withers Term Expires November 2015 Julie Castillo-Rogez Term Expires October 2016 Jani Radebaugh Term Expires October 2016 SPONSORS 2 EXHIBITORS Platinum Exhibitor Silver Exhibitors 3 EXHIBIT BOOTH ASSIGNMENTS 206 Applied -

Download the Press Release. (144.32

16 July 2020 PR084-2020 ESA RELEASES FIRST IMAGES FROM SOLAR ORBITER The European Space Agency (ESA) has released the first images from its Solar Orbiter spacecraft, which completed its commissioning phase in mid-June and made its first close approach to the Sun. Shortly thereafter, the European and U.S. science teams behind the mission’s ten instruments were able to test the entire instrument suite in concert for the first time. Despite the setbacks the mission teams had to contend with during commissioning of the probe and its instruments in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first images received are outstanding. The Sun has never been imaged this close up before. During its first perihelion, the point in the spacecraft’s elliptical orbit closest to the Sun, Solar Orbiter got to within 77 million kilometres of the star’s surface, about half the distance between the Sun and Earth. The spacecraft will eventually make much closer approaches; it is now in its cruise phase, gradually adjusting its orbit around the Sun. Once in its science phase, which will commence in late 2021, the spacecraft will get as close as 42 million kilometres, closer than the planet Mercury. The spacecraft’s operators will gradually tilt its orbit to get the first proper view of the Sun’s poles. Solar Orbiter first images here Launched during the night of 9 to 10 February, Solar Orbiter is on its way to the Sun on a voyage that will take a little over two years and a science mission scheduled to last between five and nine years. -

Lis Full CV 2021.Pages

Curriculum Vitae Dariusz C. (Darek) Lis Educa7on 1985 – 1989 University of MassachuseEs, Amherst, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Ph. D. 1981 – 1985 University of Warsaw, Department of Physics. Professional Experience 1989 – California Ins7tute of Technology. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Scien7st 2019 –. Research Fellow in Physics 1989 – 1992; Senior Research Fellow in Physics (Research Assistant Professor) 1992 – 1998; Senior Research Associate in Physics (Research Professor) 1998 – 2015; Deputy Director, Caltech Submillimeter Observatory 2009 – 2014; Visi7ng Associate in Physics 2015 – 2020. 2014 – 2019 Sorbonne University (Pierre and Marie Curie University), Paris Observatory (PSL University). Professor (Professeur des universités 1ère classe); Director, Laboratory for Studies of Radia7on and MaEer in Astrophysics and Atmospheres (UMR 8112). 1985 – 1989 University of MassachuseEs. Research Assistant, Five College Radio Astronomy Observatory. Visi7ng Appointments 2013 École normale supérieure. Visi7ng Professor (Professeur des universités 1ère classe invité). 2011 University of Bordeaux 1. Visi7ng Associate Professor (Maître de conférences invité). 2007 Paris Observatory. Visi7ng Senior Astronomer (Astronome invité). 2003 Max Planck Ins7tute for Radio Astronomy. Visi7ng Scien7st. 1992 – 1994 University of California, Los Angeles. Lecturer. Awards 2014 NASA Group Achievement Award, U.S. Herschel HIFI Instrument Team. 2010 NASA Group Achievement Award, Herschel HIFI Hardware Development Team. 1985 Minister of Science and Higher Learning Fellowship, Poland. Research Astrophysics and astrochemistry of the interstellar medium, star forma7on. Evolu7on of molecular complexity in astrophysical environments. Vola7le composi7on of comets and the origin of Earth’s oceans. Submillimeter heterodyne instrumenta7on. Cometary research featured on Na7onal Geographic, CBC Quirks & Quarks, and in Scien7fic American. Astrophysics Data System: 254 refereed publica7ons, 11,500 cita7ons. Books edited: Submillimeter Astrophysics and Technology: A Symposium Honoring Thomas G. -

World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency

Supplemental File S1 for the article “World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency” published in BioScience by William J. Ripple, Christopher Wolf, Thomas M. Newsome, Phoebe Barnard, and William R. Moomaw. Contents: List of countries with scientist signatories (page 1); List of scientist signatories (pages 1-319). List of 153 countries with scientist signatories: Albania; Algeria; American Samoa; Andorra; Argentina; Australia; Austria; Bahamas (the); Bangladesh; Barbados; Belarus; Belgium; Belize; Benin; Bolivia (Plurinational State of); Botswana; Brazil; Brunei Darussalam; Bulgaria; Burkina Faso; Cambodia; Cameroon; Canada; Cayman Islands (the); Chad; Chile; China; Colombia; Congo (the Democratic Republic of the); Congo (the); Costa Rica; Côte d’Ivoire; Croatia; Cuba; Curaçao; Cyprus; Czech Republic (the); Denmark; Dominican Republic (the); Ecuador; Egypt; El Salvador; Estonia; Ethiopia; Faroe Islands (the); Fiji; Finland; France; French Guiana; French Polynesia; Georgia; Germany; Ghana; Greece; Guam; Guatemala; Guyana; Honduras; Hong Kong; Hungary; Iceland; India; Indonesia; Iran (Islamic Republic of); Iraq; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Jamaica; Japan; Jersey; Kazakhstan; Kenya; Kiribati; Korea (the Republic of); Lao People’s Democratic Republic (the); Latvia; Lebanon; Lesotho; Liberia; Liechtenstein; Lithuania; Luxembourg; Macedonia, Republic of (the former Yugoslavia); Madagascar; Malawi; Malaysia; Mali; Malta; Martinique; Mauritius; Mexico; Micronesia (Federated States of); Moldova (the Republic of); Morocco; Mozambique; Namibia; Nepal; -

The French Savants, and the Earth–Sun Distance: a R´Esum´E

MEETING VENUS C. Sterken, P. P. Aspaas (Eds.) The Journal of Astronomical Data 19, 1, 2013 The French Savants, and the Earth–Sun Distance: a R´esum´e Suzanne D´ebarbat SYRTE, Observatoire de Paris, Bureau des longitudes 61, avenue de l’Observatoire, 75014 Paris, France Abstract. Transits of Venus have played an important rˆole during more than two centuries in determining the Earth–Sun distance. In 2012, three centuries after Cassini’s death, the issue has been finally settled by the latest Resolution formulated by the International Astronomical Union. 1. Prologue From Antiquity up to the sixteenth century, values of the Earth–Sun distance were considered as being 10 to 20 times smaller than nowadays. Then came the Coper- nican revolution that brought new ideas about the solar system, followed by Jo- hannes Kepler (1571–1630) and Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) and, later in the seven- teenth century, Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695), Jean Picard (1620–1682), Gian- Domenico Cassini (1625–1712) and Isaac Newton (1643–1727) with his Principia. Powerful instruments were built, new pluridisciplinary groups formed, and novel con- cepts were presented. In France, Louis XIV created in 1666 the Acad´emie Royale des Sciences and the following year, 1667, the Observatoire Royal on the southern outskirts of the capital. Soon after, he demanded, from his academicians, a new geographical map of his kingdom. Picard presented ideas and new instruments to be built, and he performed a careful determination of the dimension of the Earth, along a meridian line represented by the symmetry axis of the observatory under construction. -

European Architecture 1750-1890

Oxford History of Art European Architecture 1750-1890 Barry Bergdoll O X fO R D UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 0 x2 6 d p Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bombay Calcutta Cape Town Dares Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the U K and in certain other countries © Barry Bergdoll 2000 First published 2000 by Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the proper permission in writing o f Oxford University Press. Within the U K, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the purpose of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of the licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms and in other countries should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, byway o f trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.