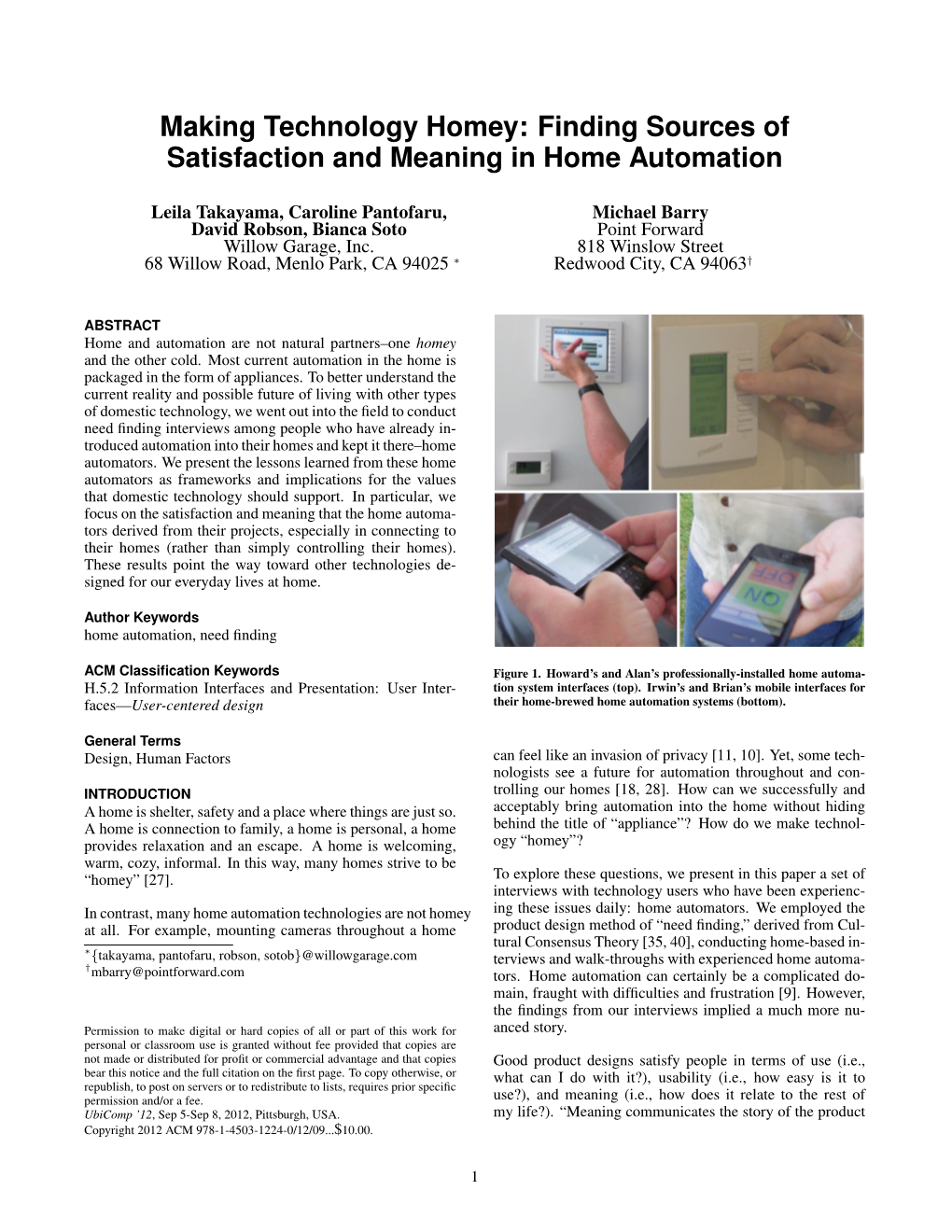

Home Automation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Designing Technology for Domestic Spaces: a Kitchen Manifesto 1

DRAFT COPY VERSION 24. NOT FOR PUBLICATION OR DISTRIBUTION. Designing technology for domestic spaces: A Kitchen Manifesto 1 Genevieve Bell Joseph ‘Jofish’ Kaye Peoples and Practices Research Counter Intelligence Intel Corporation MIT Media Lab Jenny Nelson (Doris Day): “Oh boy! This kitchen doesn’t need a woman!” Bruce Templeton (Rod Taylor): “Jenny, you’re the one good thing in this kitchen I didn’t make provision for.” Glass Bottom Boat (Tashlin 1966) Glass Bottom Boat is one of those Hollywood movies – ditzy blonde disrupts the orderly life of rational scientist. Bruce Templeton, a NASA physicist, played by Rod Taylor, has designed himself the perfect home, instrumented with labor saving devices. His kitchen is a showpiece of streamlined functionality. Cooking becomes just another task, one that can be controlled, contained and automated with appliances popping out of counter tops and self-cleaning dishes and floors. This kitchen confounds Doris Day’s character, renders her feminine skills obsolete, and she is compelled to declare that there is no place for her in this kitchen of the future. The declaration that “this kitchen doesn’t need a woman” aptly captures a theme that reverberates through this paper. In creating technology for the home, in particular for the kitchen, technologists have forgotten that 1 This paper began as a hyperbolic conversation at MIT’s Media Lab in Boston. A flurry of emails followed but the paper was written in two co-present moments. The first draft, fueled by “Vietnamese coffee’, was written over two nights in the middle of a Boston summer. The second draft was composed at a series of café tables in and around Dublin, and in the hop-rich scent of the Media Lab Europe’s new facility in the old Guinness Brewery’s Hop Store. -

Exergames and the “Ideal Woman”

Make Room for Video Games: Exergames and the “Ideal Woman” by Julia Golden Raz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christian Sandvig, Chair Professor Susan Douglas Associate Professor Sheila C. Murphy Professor Lisa Nakamura © Julia Golden Raz 2015 For my mother ii Acknowledgements Words cannot fully articulate the gratitude I have for everyone who has believed in me throughout my graduate school journey. Special thanks to my advisor and dissertation chair, Dr. Christian Sandvig: for taking me on as an advisee, for invaluable feedback and mentoring, and for introducing me to the lab’s holiday white elephant exchange. To Dr. Sheila Murphy: you have believed in me from day one, and that means the world to me. You are an excellent mentor and friend, and I am truly grateful for everything you have done for me over the years. To Dr. Susan Douglas: it was such a pleasure teaching for you in COMM 101. You have taught me so much about scholarship and teaching. To Dr. Lisa Nakamura: thank you for your candid feedback and for pushing me as a game studies scholar. To Amy Eaton: for all of your assistance and guidance over the years. To Robin Means Coleman: for believing in me. To Dave Carter and Val Waldren at the Computer and Video Game Archive: thank you for supporting my research over the years. I feel so fortunate to have attended a school that has such an amazing video game archive. -

PLANNING for INNOVATION Understanding China’S Plans for Technological, Energy, Industrial, and Defense Development

PLANNING FOR INNOVATION Understanding China’s Plans for Technological, Energy, Industrial, and Defense Development A report prepared for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Tai Ming Cheung Thomas Mahnken Deborah Seligsohn Kevin Pollpeter Eric Anderson Fan Yang July 28, 2016 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE ON GLOBAL CONFLICT AND COOPERATION Disclaimer: This research report was prepared at the request of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commis- sion’s website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of US-China economic relations and their implications for US security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 108-7. However, it does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission or any individual Commissioner of the views or conclusions expressed in this commissioned research report. The University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation (IGCC) addresses global challenges to peace and prosperity through academically rigorous, policy-relevant research, train- ing, and outreach on international security, economic development, and the environment. IGCC brings scholars together across social science and lab science disciplines to work on topics such as regional security, nuclear proliferation, innovation and national security, development and political violence, emerging threats, and climate change. IGCC is housed within the School -

Appliances and Their Impact: the Ownership of Domestic Technology and Time Spent on Household Work

The British Journal of Sociology 2004 Volume 55 Issue 3 Appliances and their impact: the ownership of domestic technology and time spent on household work Michael Bittman, James Mahmud Rice and Judy Wajcman Abstract Ever since the appearance of Vanek’s pioneering article in 1974, there has been a controversy about whether ‘labour saving’ domestic appliances actually save labour time. Vanek argued that time spent in housework had barely changed since 1926, despite the diffusion of practically every known domestic appliance over this period. Gershuny and Robinson challenge Vanek’s ‘constancy of housework’ thesis, arguing that, between 1965 and 1985, domestic technology has significantly reduced the weekly hours of women’s routine housework. Although there is much talking past each other, none of the protagonists in this dispute have any direct data about which households own or do not own domestic appliances. Instead, they all rely on the passage of the years as a proxy for ownership of domestic appliances, since a higher proportion of contemporary households now own domestic appliances. The Australian 1997 Time Use Survey (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1998b) is rare among official surveys, as it simultaneously provides detailed information on time spent in housework and an inventory of household appliances. The analysis of this data show that domestic technology rarely reduces women’s unpaid working time and even, paradoxically, produces some increases in domestic labour. The domestic division of labour by gender remains remark- ably resistant to technological innovation. Keywords: Household work; time; technology; women; income Thirty years ago, in a now classic article in Scientific American,Joann Vanek (1974) announced to the world that the time non-employed women devoted to housework in the USA had not declined over the preceding half century.1 This was a strikingly counterintuitive finding. -

Buying Modernity? the Consumer Experience of Domestic Electricity in the Era of the Grid

Buying Modernity? The Consumer Experience of Domestic Electricity in the Era of the Grid A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of PhD in the Faculty of Life Sciences 2012 Emily Hankin Contents Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Declaration…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Copyright Statement…………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Chapter 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1.1. ‘More Work for Mother’: The American and British Context…… 11 1.2. Buying Modernity: Consumption and Modernity…………………….. 14 1.3. The Housewife Consumer…………………………………………………………. 19 1.4. Electrical Technologies in the Home………………………………………….. 24 1.5. Gender and Technology……………………………………………………………. 28 1.6. Methodology…………………………………………………………………………….. 31 1.7. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………… 39 Chapter 2 Supply………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 42 2.1. The National “Grid”…………………………………………………………………… 43 2.2. Competition with the Gas Industry……………………………………………. 54 2.3. Modern Architecture and British Homes…………………………………… 61 2.4. The Domestic Consumer of Electricity……………………………………….. 67 2.5. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………. 76 Chapter 3 Cleanliness…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 78 3.1. Electric Ironing………………………………………………………………………….. 81 3.2. The Constructed Ideal of Domestic Cleanliness as Modernity……. 88 3.3. Vacuum Cleaners………………………………………………………………………. 92 3.4. Consumers of Electric -

Fridge Space: Journeys of the Domestic Refrigerator

FRIDGE SPACE: JOURNEYS OF THE DOMESTIC REFRIGERATOR by HELEN WATKINS A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2008 © Helen Watkins, 2008 ABSTRACT My dissertation emerges from a curiosity about the mundane objects and machines with which we live and it pauses in Britain’s kitchens to ask what we might learn from looking in the fridge. Considered by many to be a rather ordinary and unremarkable appliance, the refrigerator forms a virtually ubiquitous backdrop to routine activities of feeding, provisioning and storing, but rarely is it brought into explicit focus. This study traces the ‘career’ of the mechanical refrigerator and is based upon interviews and archival work in Britain. I unravel intersecting histories and geographies of cooling, discuss a global trade in ice, explore changing understanding of the nature of heat and cold and show how varied ideas and technologies contributed to achieving the creation of artificial cold. The means by which these techniques were translated into the home is central to my discussion and I show how the domestication of refrigeration also played a role in the reconfiguration of associated practices, such as freezing, shopping and eating. I consider the process of normalisation through which refrigerators shifted category from novel products to essential appliances and argue that in many ways the refrigerator has now become integral to the constitution of domestic space. My research follows the lifecourse of the refrigerator and its journeys through multiple sites and spaces, enabling me to analyse diverse refrigerator knowledges and practices from repair shops and recycling facilities to scrap yards and museums, in addition to the home. -

The Multiplayer Game: User Identity and the Meaning Of

THE MULTIPLAYER GAME: USER IDENTITY AND THE MEANING OF HOME VIDEO GAMES IN THE UNITED STATES, 1972-1994 by Kevin Donald Impellizeri A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Fall 2019 Copyright 2019 Kevin Donald Impellizeri All Rights Reserved THE MULTIPLAYER GAME: USER IDENTITY AND THE MEANING OF HOME VIDEO GAMES IN THE UNITED STATES, 1972-1994 by Kevin Donald Impellizeri Approved: ______________________________________________________ Alison M. Parker, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of History Approved: ______________________________________________________ John A. Pelesko, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: ______________________________________________________ Douglas J. Doren, Ph.D. Interim Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education and Dean of the Graduate College I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Katherine C. Grier, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation. I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Arwen P. Mohun, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Jonathan Russ, Ph.D. -

Autonomous Exchanges: Human-Machine Autonomy in the Automated Media Economy

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Summer 6-22-2018 Autonomous Exchanges: Human-Machine Autonomy in the Automated Media Economy Christopher Cox [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Cox, Christopher, "Autonomous Exchanges: Human-Machine Autonomy in the Automated Media Economy." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2018. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUTONOMOUS EXCHANGES: HUMAN-MACHINE AUTONOMY IN THE AUTOMATED MEDIA ECONOMY by CHRISTOPHER M. Cox Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey ABSTRACT Contemporary discourses and representations of automation stress the impending “autonomy” of automated technologies. From pop culture depictions to corporate white papers, the notion of auton- omous technologies tends to enliven dystopic fears about the threat to human autonomy or utopian po- tentials to help humans experience unrealized forms of autonomy. This project offers a more nuanced perspective, rejecting contemporary notions of automation as inevitably vanquishing or enhancing hu- man autonomy. Through a discursive analysis of industrial “deep texts” that offer considerable insights into the material development of automated media technologies, I argue for contemporary automation to be understood as a field for the exchange of autonomy, a human-machine autonomy in which auton- omy is exchanged as cultural and economic value. -

Are We Worthy of Our Kitchens? Christine Rosen

Are We Worthy of Our Kitchens? Christine Rosen One of the best recent advertising campaigns is for a new line of high- end washers and dryers made by General Electric. A supermodel and a dorky scientist collide on the street, falling unexpectedly in love, uniting brains and beauty, utility and aestheticism. The fruit of this union is the household appliance of the future—sophisticated, sleek, an electronic image of domestic bliss for our times. The perfect washer and dryer create the perfect family. Given the great range and power of our contemporary technologies, it is hardly surprising that our expectations for modern machines are especially high at home. We seek movie-quality entertainment with our oversized, flat-panel, high-definition televisions. We seek business- quality communication by installing satellite-powered Internet access in our home offices. We seek restaurant-quality kitchens with our six-burner stovetops and cappuccino-making machines. We want the latest high-tech contrivance or convenience, hoping that it will make old jobs easier, or that it will fulfill new longings we never knew existed. At the same time, some of the most remarkable household appliances are now so mundane that we rarely think of them as technologies at all. Consider—or reconsider—the washing machine. In many homes, it is relegated to the basement or some other hidden corner. It is used often but not given much attention by its owner unless it breaks. Most house- holds still have reasonably priced models, almost always in white, so loud and unattractive that they are kept out of public view. -

Operation Manual Combimaster Plus

® ® CombiMaster Plus / CombiMaster Original operating instructions RATIONAL ServicePlus The all-inclusive package for an all-round service. We want to maximise your return on investment from the very start. Over the entire service life and without any hidden costs. FREE OF CHARGE! - On-site training We demonstrate to your kitchen team in your own kitchen how our appliances work and how they can be best deployed to suit your specific requirements. FREE OF CHARGE! - RATIONAL ConnectedCooking Connect your RATIONAL appliances easily with the latest network solution for professional kitchens. With ConnectedCooking you always have everything under control: Simple appliance management, remote access function via smart phone, automatic HACCP documentation or you can download recipes from the RATIONAL library conveniently onto your devices. Simply log in at ConnectedCooking.com ® FREE OF CHARGE! - Chef✆Line We offer a telephone consulting service to answer any questions you have about applications or recipes. Fast, uncomplicated and from one chef to another, 365 days a ® year. You can contact the Chef✆Line at Tel. +44 7743389863 2 / 112 RATIONAL ServicePlus RATIONAL SERVICE PARTNERS Our appliances are reliable and have a long service life. However if you should encounter technical difficulties, the RATIONAL SERVICE PARTNERS can provide swift and efficient help. Guaranteed spare parts supply and a weekend call-out team included: Tel. +44 1582 480388 2-year warranty We offer a 24-month warranty valid from the date of initial installation, provided that your appliance is fully and correctly registered with us. You can do this comfortably online at www.rational-online.com/warranty or by sending us the postcard attached to this manual. -

Defamiliarization and the Design of Domestic Technologies

Making by Making Strange: Defamiliarization and the Design of Domestic Technologies GENEVIEVE BELL Intel Research MARK BLYTHE University of York and PHOEBE SENGERS Cornell University This article argues that because the home is so familiar, it is necessary to make it strange, or defa- miliarize it, in order to open its design space. Critical approaches to technology design are of both practical and social importance in the home. Home appliances are loaded with cultural associations such as the gendered division of domestic labor that are easy to overlook. Further, homes are not the same everywhere—even within a country. Peoples’ aspirations and desires differ greatly across and between cultures. The target of western domestic technology design is often not the user, but the consumer. Web refrigerators that create shopping lists, garbage cans that let advertisers know what is thrown away, cabinets that monitor their contents and order more when supplies are low are central to current images of the wireless, digital home of the future. Drawing from our research in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Asia, we provide three different narratives of de- familiarization. A historical reading of American kitchens provides a lens with which to scrutinize new technologies of domesticity, an ethnographic account of an extended social unit in England problematizes taken-for-granted domestic technologies, and a comparative ethnography of the role of information and communication technologies in the daily lives of urban Asia’s middle classes reveals the ways in which new technologies can be captured and domesticated in unexpected ways. In the final section of the article, we build on these moments of defamiliarization to suggest a broad set of challenges and strategies for design in the home. -

Making Domestic Technology Meaningful

INARI AALTOJÄRVI Making Domestic Technology Meaningful From purification to emotions ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Board of the School of Social Sciences and Humanities of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Auditorium A1 of the Main Building, Kalevantie 4, Tampere, on October 17th, 2014, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE INARI AALTOJÄRVI Making Domestic Technology Meaningful From purification to emotions Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1968 Tampere University Press Tampere 2014 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere School of Social Sciences and Humanities Finland Copyright ©2014 Tampere University Press and the author Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Distributor: [email protected] http://granum.uta.fi Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1968 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1454 ISBN 978-951-44-9554-0 (print) ISBN 978-951-44-9555-7 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://tampub.uta.fi Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print 441 729 Tampere 2014 Painotuote Acknowledgements I have been fortunate to have financial, academic and mental help and support from numerous people and projects throughout this study. First and foremost, I want to thank my supervisors, Ilkka Arminen and Jari Aro, for their constructive criticism and faith in my work. You have both taught me how to become a researcher. Besides offering your expertise, you also took time to get to know me and my working methods so that our collaboration was fluent. In addition, Ilkka is the one to thank (or blame) for starting my academic career, for he also supervised my master's thesis at the University of Tampere and suggested I might want to apply for the graduate school and start off doctoral studies.