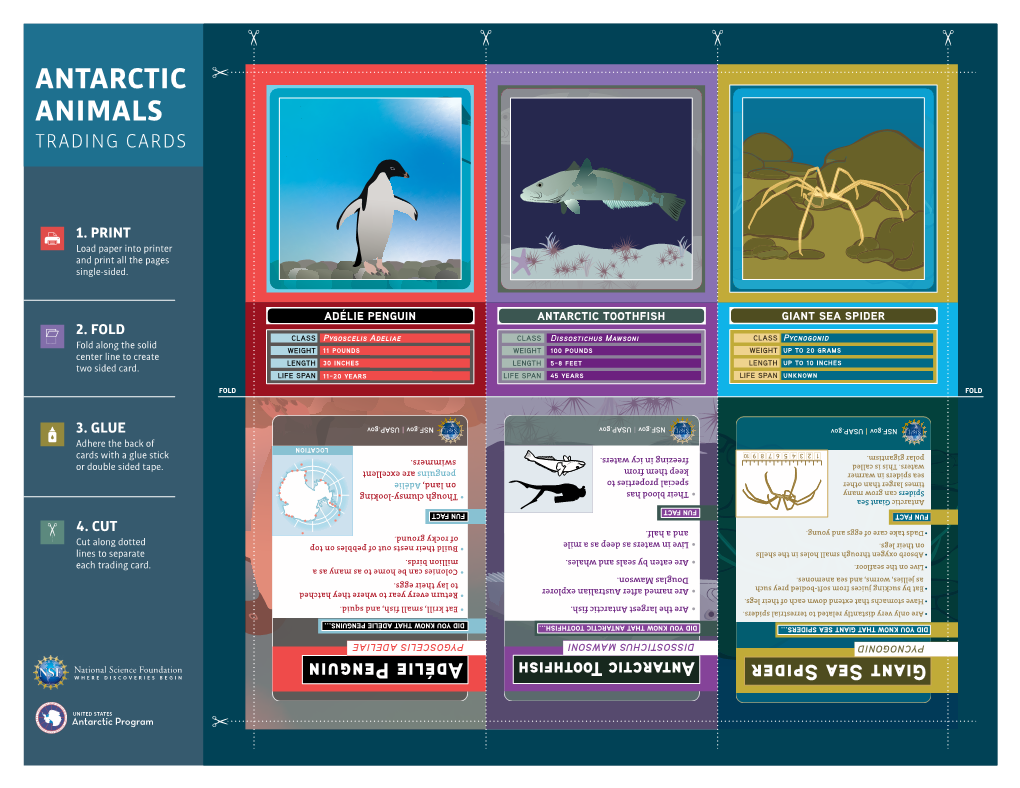

Antarctic Animals Trading Cards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antarctic Treaty System And

The Antarctic Treaty System and Law During the first half of the 20th century a series of territorial claims were made to parts of Antarctica, including New Zealand's claim to the Ross Dependency in 1923. These claims created significant international political tension over Antarctica which was compounded by military activities in the region by several nations during the Second World War. These tensions were eased by the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957-58, the first substantial multi-national programme of scientific research in Antarctica. The IGY was pivotal not only in recognising the scientific value of Antarctica, but also in promoting co- operation among nations active in the region. The outstanding success of the IGY led to a series of negotiations to find a solution to the political disputes surrounding the continent. The outcome to these negotiations was the Antarctic Treaty. The Antarctic Treaty The Antarctic Treaty was signed in Washington on 1 December 1959 by the twelve nations that had been active during the IGY (Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, United Kingdom, United States and USSR). It entered into force on 23 June 1961. The Treaty, which applies to all land and ice-shelves south of 60° South latitude, is remarkably short for an international agreement – just 14 articles long. The twelve nations that adopted the Treaty in 1959 recognised that "it is in the interests of all mankind that Antarctica shall continue forever to be used exclusively for peaceful purposes and shall not become the scene or object of international discord". -

Asynchronous Antarctic and Greenland Ice-Volume Contributions to the Last Interglacial Sea-Level Highstand

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12874-3 OPEN Asynchronous Antarctic and Greenland ice-volume contributions to the last interglacial sea-level highstand Eelco J. Rohling 1,2,7*, Fiona D. Hibbert 1,7*, Katharine M. Grant1, Eirik V. Galaasen 3, Nil Irvalı 3, Helga F. Kleiven 3, Gianluca Marino1,4, Ulysses Ninnemann3, Andrew P. Roberts1, Yair Rosenthal5, Hartmut Schulz6, Felicity H. Williams 1 & Jimin Yu 1 1234567890():,; The last interglacial (LIG; ~130 to ~118 thousand years ago, ka) was the last time global sea level rose well above the present level. Greenland Ice Sheet (GrIS) contributions were insufficient to explain the highstand, so that substantial Antarctic Ice Sheet (AIS) reduction is implied. However, the nature and drivers of GrIS and AIS reductions remain enigmatic, even though they may be critical for understanding future sea-level rise. Here we complement existing records with new data, and reveal that the LIG contained an AIS-derived highstand from ~129.5 to ~125 ka, a lowstand centred on 125–124 ka, and joint AIS + GrIS contributions from ~123.5 to ~118 ka. Moreover, a dual substructure within the first highstand suggests temporal variability in the AIS contributions. Implied rates of sea-level rise are high (up to several meters per century; m c−1), and lend credibility to high rates inferred by ice modelling under certain ice-shelf instability parameterisations. 1 Research School of Earth Sciences, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. 2 Ocean and Earth Science, University of Southampton, National Oceanography Centre, Southampton SO14 3ZH, UK. 3 Department of Earth Science and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, University of Bergen, Allegaten 41, 5007 Bergen, Norway. -

Balaenoptera Bonaerensis – Antarctic Minke Whale

Balaenoptera bonaerensis – Antarctic Minke Whale compared to B. bonaerensis. This smaller form, termed the “Dwarf” Minke Whale, may be genetically different from B. bonaerensis, and more closely related to the North Pacific Minke Whales, and thus has been classified B. acutorostrata (Wada et al. 1991; IWC 2001). This taxonomic position, although somewhat controversial, has been accepted by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). Assessment Rationale The current IWC global estimate of abundance of Antarctic Dr. Meike Scheidat Minke Whales is about 500,000 individuals. The abundance estimates declined from about 700,000 for the second circumpolar set of abundance survey cruises Regional Red List status (2016) Least Concern* (1985/86 to 1990/91) to about 500,000 for the third National Red List status (2004) Least Concern (1991/92 to 2003/04). Although this decline was not statistically significant, the IWC Scientific Committee does Reasons for change No change consider these results to reflect a change. However, Global Red List status (2008) Data Deficient whether this change is genuine or attributed to greater proportions of pack ice limiting the survey extent, has not TOPS listing (NEMBA) (2007) None yet been determined. More detailed results from an CITES listing (1986) Appendix I assessment model are available for the mid-Indian to the mid-Pacific region, and suggest that the population Endemic No increased to a peak in 1970 and then declined, with it *Watch-list Data being unclear whether this decline has levelled off or is still continuing past 2000. -

Species Status Assessment Emperor Penguin (Aptenodytes Fosteri)

SPECIES STATUS ASSESSMENT EMPEROR PENGUIN (APTENODYTES FOSTERI) Emperor penguin chicks being socialized by male parents at Auster Rookery, 2008. Photo Credit: Gary Miller, Australian Antarctic Program. Version 1.0 December 2020 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ecological Services Program Branch of Delisting and Foreign Species Falls Church, Virginia Acknowledgements: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Penguins are flightless birds that are highly adapted for the marine environment. The emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) is the tallest and heaviest of all living penguin species. Emperors are near the top of the Southern Ocean’s food chain and primarily consume Antarctic silverfish, Antarctic krill, and squid. They are excellent swimmers and can dive to great depths. The average life span of emperor penguin in the wild is 15 to 20 years. Emperor penguins currently breed at 61 colonies located around Antarctica, with the largest colonies in the Ross Sea and Weddell Sea. The total population size is estimated at approximately 270,000–280,000 breeding pairs or 625,000–650,000 total birds. Emperor penguin depends upon stable fast ice throughout their 8–9 month breeding season to complete the rearing of its single chick. They are the only warm-blooded Antarctic species that breeds during the austral winter and therefore uniquely adapted to its environment. Breeding colonies mainly occur on fast ice, close to the coast or closely offshore, and amongst closely packed grounded icebergs that prevent ice breaking out during the breeding season and provide shelter from the wind. Sea ice extent in the Southern Ocean has undergone considerable inter-annual variability over the last 40 years, although with much greater inter-annual variability in the five sectors than for the Southern Ocean as a whole. -

MARINE FISHERIES Fishing in the Ice: Is It Sustainable?

NIWA Water & Atmosphere 11(3) 2003 MARINE FISHERIES Fishing in the ice: is it sustainable? Stuart Hanchet In recent years an exploratory fishery for The Ross Sea fishery is the southernmost fishery Antarctic toothfish has developed in in the world, and ice conditions and extreme Peter Horn the Ross Sea and in the Southern Ocean to cold make fishing both difficult and dangerous. Michael Stevenson the north. Fisheries in Antarctic waters are During most of the year the Ross Sea is covered managed by CCAMLR (Commission for by ice. However, during January and February the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living areas of open water (called polynas) form, Resources). CCAMLR takes a precautionary which enable access to the continental shelf and approach to fisheries management and also slope. Longline vessels from New Zealand, has a strong mandate from its members to take South Africa and Russia start working in the A better into account ecosystem effects of fishing. In deep south at this time, but as sea ice forms knowledge of the conjunction with the Ministry of Fisheries they move north and by May are restricted to biology and habits (MFish) and New Zealand fishing companies, the northernmost fishing grounds. Antarctic NIWA has been involved in developing research toothfish has formed over 95% of the fishery’s of the Antarctic programmes to help ensure that the fishery is catch, which has steadily increased from about toothfish is needed both sustainable and has minimal impact on the 40 t in 1998 to over 1800 t in 2003. surrounding ecosystem. to manage a NIWA’s research related to the toothfish in the Ross Sea has concentrated on catch sampling sustainable fishery methods, genetics, age and growth, Antarctic toothfish get for this species in very big. -

Good Whale Hunting Robert L

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications, Agencies and Staff of the .SU . U.S. Department of Commerce Department of Commerce 2003 Good Whale Hunting Robert L. Pitman National Marine Fisheries Service Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub Pitman, Robert L., "Good Whale Hunting" (2003). Publications, Agencies and Staff of ht e U.S. Department of Commerce. 509. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub/509 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Commerce at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications, Agencies and Staff of the .SU . Department of Commerce by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. NATURALIST AT LARGE Good Whale Hunting Two tantalizing Russian reports take the author on a quest to the Antarctic, in search of two previously unrecognized kinds of killer whale. By Robert L. Pitman hey always remind me of witch’s hats—a little bit of THalloween in the winter wonderland. Looking across a flat plain of frozen Antarctic sea ice, I watch as a herd of killer whales swims along a lead—a long, narrow crack in the six- foot-thick ice. The fins of the males are black isosceles triangles, five feet tall, and they look like a band of trick- or-treaters coming our way. I am on board the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker Polar Star as it back-and-rams the frozen ocean to open up a fourteen- mile-long channel into McMurdo Sta- tion, fifty feet at a whack. -

Haswell Island (Haswell Island and Adjacent Emperor Penguin Rookery on Fast Ice)

Measure 5 (2016) Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 127 Haswell Island (Haswell Island and Adjacent Emperor Penguin Rookery on Fast Ice) 1. Description of values to be protected The area includes Haswell Island with its littoral zone and adjacent fast ice when present. Haswell Island was discovered in 1912 by the Australian Antarctic Expedition led by D. Mawson. It was named after William Haswell, professor of biology who rendered assistance to the expedition. Haswell is the biggest island of the same-name archipelago, with a height of 93 meters and 0,82 sq.meters in area. The island is at 2,5 km distance from the Russian Mirny Station operational from 1956. At East and South-East of the island, there is a large colony of Emperor penguins (Aptenodytes forsteri) on fast ice. The Haswell Island is a unique breeding site for almost all breeding bird species in East Antarctica including the: Antarctic petrel (Talassoica antarctica), Antarctic fulmar (Fulmarus glacioloides), Cape petrel (Daption capense), Snow petrel (Pagodroma nivea), Wilson’s storm petrel (Oceanites oceanicus), South polar skua (Catharacta maccormicki), Lonnberg skua Catharacta antarctica lonnbergi and Adelie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae). The Area supports five species of pinnipeds, including the Ross seal (Ommatophoca rossii) which falls in the protected species category. ATCM VIII (Oslo, 1975) approved its designation as SSSI 7 on the aforementioned grounds after a proposal by the USSR. Map 1 shows the location of the Haswell Islands (except Vkhodnoy Island), Mirny Station, and logistic activity sites. It was renamed and renumbered as ASPA No. 127 by Decision 1 (2002). -

Energetics of the Antarctic Silverfish, Pleuragramma Antarctica, from the Western Antarctic Peninsula

Chapter 8 Energetics of the Antarctic Silverfish, Pleuragramma antarctica, from the Western Antarctic Peninsula Eloy Martinez and Joseph J. Torres Abstract The nototheniid Pleuragramma antarctica, commonly known as the Antarctic silverfish, dominates the pelagic fish biomass in most regions of coastal Antarctica. In this chapter, we provide shipboard oxygen consumption and nitrogen excretion rates obtained from P. antarctica collected along the Western Antarctic Peninsula and, combining those data with results from previous studies, develop an age-dependent energy budget for the species. Routine oxygen consumption of P. antarctica fell in the midrange of values for notothenioids, with a mean of 0.057 ± −1 −1 0.012 ml O2 g h (χ ± 95% CI). P. antarctica showed a mean ammonia-nitrogen excretion rate of 0.194 ± 0.042 μmol NH4-N g−1 h−1 (χ ± 95% CI). Based on current data, ingestion rates estimated in previous studies were sufficient to cover the meta- bolic requirements over the year classes 0–10. Metabolism stood out as the highest energy cost to the fish over the age intervals considered, initially commanding 89%, gradually declining to 67% of the annual energy costs as the fish aged from 0 to 10 years. Overall, the budget presented in the chapter shows good agreement between ingested and combusted energy, and supports the contention of a low-energy life- style for P. antarctica, but it also resembles that of other pelagic species in the high percentage of assimilated energy devoted to metabolism. It differs from more tem- perate coastal pelagic fishes in its large investment in reproduction and its pattern of slow steady growth throughout a relatively long lifespan. -

Joint Conference of the History EG and Humanities and Social Sciences

Joint conference of the History EG and Humanities and Social Sciences EG "Antarctic Wilderness: Perspectives from History, the Humanities and the Social Sciences" Colorado State University, Fort Collins (USA), 20 - 23 May 2015 A joint conference of the History Expert Group and the Humanities and Social Sciences Expert Group on "Antarctic Wilderness: Perspectives from History, the Humanities and the Social Sciences" was held at Colorado State University in Fort Collins (USA) on 20-23 May 2015. On Wednesday (20 May) we started with an excursion to the Rocky Mountain National Park close to Estes. A hike of two hours took us along a former golf course that had been remodelled as a natural plain, and served as a fitting site for a discussion with park staff on “comparative wilderness” given the different connotations of that term in isolated Antarctica and comparatively accessible Colorado. After our return to Fort Collins we met a group of members of APECS (Association of Polar Early Career Scientists), with whom we had a tour through the New Belgium Brewery. The evening concluded with a screening of the film “Nightfall on Gaia” by the anthropologist Juan Francisco Salazar (Australia), which provides an insight into current social interactions on King George Island and connections to the natural and political complexities of the sixth continent. The conference itself was opened by on Thursday (21 May) by Diana Wall, head of the School of Global Environmental Sustainability at the Colorado State University (CSU). Andres Zarankin (Brazil) opened the first session on narratives and counter narratives from Antarctica with his talk on sealers, marginality, and official narratives in Antarctic history. -

Spatial Association Between Hotspots of Baleen Whales and Demographic Patterns of Antarctic Krill Euphausia Superba Suggests Size-Dependent Predation

Vol. 405: 255–269, 2010 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published April 29 doi: 10.3354/meps08513 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Spatial association between hotspots of baleen whales and demographic patterns of Antarctic krill Euphausia superba suggests size-dependent predation Jarrod A. Santora1, 2,*, Christian S. Reiss2, Valerie J. Loeb3, Richard R. Veit4 1Farallon Institute for Advanced Ecosystem Research, PO Box 750756, Petaluma, California 94952, USA 2Antarctic Ecosystem Research Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, 3333 Torrey Pines Ct., La Jolla, California 92037, USA 3Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, 8272 Moss Landing Road, Moss Landing, California 95039, USA 4Biology Department, College of Staten Island, City University of New York, 2800 Victory Boulevard, Staten Island, New York 10314, USA ABSTRACT: We examined the spatial association between baleen whales and their principal prey, Antarctic krill Euphausia superba near the South Shetland Islands (Antarctic Peninsula) using data collected by the US Antarctic Marine Living Resources (AMLR) program during January surveys from 2003 through 2007. Whale distributions were determined using ship-based visual surveys, while data on krill distribution, abundance, and demographic characteristics were derived from net hauls. Approximately 25 000 km of transects and 500 net hauls were sampled over 5 yr. We defined hotspots based on statistical criteria to describe persistent areas of occurrence of both whales and krill. Hotspots were identified, and whales and krill length-maturity classes exhibited distinct spatial seg- regation in their distribution patterns. We found that baleen whales aggregated to krill hotspots that differed in size structure. Humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae were associated with small (<35 mm) juvenile krill in Bransfield Strait, whereas fin whales Balaenoptera physalus were associ- ated with large (>45 mm) mature krill located offshore. -

Feeding and Energy Budgets of Larval Antarctic Krill Euphausia Superba in Summer

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 257: 167–177, 2003 Published August 7 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Feeding and energy budgets of larval Antarctic krill Euphausia superba in summer Bettina Meyer1,*, Angus Atkinson2, Bodo Blume1, Ulrich V. Bathmann1 1Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Department of Pelagic Ecosystems, Handelshafen 12, 27570 Bremerhaven, Germany 2British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, United Kingdom ABSTRACT: The physiological condition and feeding activity of the dominant larval stages of Eu- phausia superba (calyptopis stage III, furcilia stages I and II) were investigated from February to March 2000 at the Rothera Time Series monitoring station (67° 34’ S, 68° 07’ W, Adelaide Island, West- ern Antarctic Peninsula). A dense phytoplankton bloom (5 to 25 µg chl a l–1) occupied the mixed layer throughout the study period. The feeding of larvae was measured by incubating the animals in natural seawater. Food concentrations ranged from 102 to 518 µg C l–1 across experiments, and the mean daily C rations were 28% body C for calyptosis stage III (CIII), 25% for furcilia stage I (FI) and 15% for FII. The phytoplankton, dominated by diatoms and motile prey taxa, ranged from 8 to 79 µm in size. Across this size spectrum of diatoms, CIII cleared small cells most efficiently, as did FI to a lesser degree. FII, however, showed no clear tendency for a specific cell size. Across the measured size spectrum of the motile taxa, all larvae stages showed a clear preference towards the larger cells. Estimated C assimi- lation efficiencies were high, from 70 to 92% (mean 84%). -

Fall Feeding Aggregations of Fin Whales Off Elephant Island (Antarctica)

SC/64/SH9 Fall feeding aggregations of fin whales off Elephant Island (Antarctica) BURKHARDT, ELKE* AND LANFREDI, CATERINA ** * Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine research, Am Alten Hafen 26, 256678 Bremerhaven, Germany ** Politecnico di Milano, University of Technology, DIIAR Environmental Engineering Division Pza Leonardo da Vinci 32, 20133 Milano, Italy Abstract From 13 March to 09 April 2012 Germany conducted a fisheries survey on board RV Polarstern in the Scotia Sea (Elephant Island - South Shetland Island - Joinville Island area) under the auspices of CCAMLR. During this expedition, ANT-XXVIII/4, an opportunistic marine mammal survey was carried out. Data were collected for 26 days along the externally preset cruise track, resulting in 295 hrs on effort. Within the study area 248 sightings were collected, including three different species of baleen whales, fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus), humpback whale ( Megaptera novaeangliae ), and Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis ) and one toothed whale species, killer whale ( Orcinus orca ). More than 62% of the sightings recorded were fin whales (155 sightings) which were mainly related to the Elephant Island area (116 sightings). Usual group sizes of the total fin whale sightings ranged from one to five individuals, also including young animals associated with adults during some encounters. Larger groups of more than 20 whales, and on two occasions more than 100 individuals, were observed as well. These large pods of fin whales were observed feeding in shallow waters (< 300 m) on the north-western shelf off Elephant Island, concordant with large aggregations of Antarctic krill ( Euphausia superba ). This observation suggests that Elephant Island constitutes an important feeding area for fin whales in early austral fall, with possible implications regarding the regulation of (krill) fisheries in this area.