Draupadi - a Changing Cultural Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

Masculinity and Transnational Hindu Identity

Nidān, Volume 3, No. 2, December 2018, pp. 18-39 ISSN 2414-8636 Muscular Mahabharatas: Masculinity and Transnational Hindu Identity Sucheta Kanjilal University of Tampa [email protected] "Hence it is called Bharata. And because of its grave import, as also of the Bharatas being its topic, it is called Mahabharata. He who is versed in interpretations of this great treatise, becomes cleansed of every sin. Such a man lives in righteousness, wealth, and pleasure, and attains to Emancipation.” - Mahābhārata (18.5) translation by K. M. Ganguli Abstract The climax of the Sanskrit Mahābhārata is undeniably muscular, since it involves a kṣatriya family fighting a brutal but righteous war. Many 21st century Mahabharata adaptations not only emphasize the muscularity of the epic, but also flex these muscles in an arena beyond the Kurukṣetra battlefield: the world. Through an analysis of texts such as Chindu Sreedharan’s Epic Retold (2015) and Prem Panicker’s Bhimsen (2009), I suggest that the increased visibility of epic warrior narratives across global platforms indicates a desire to re-fashion a hypermasculine identity for Hindus in the transnational religio-political sphere. I see this as an attempt to distance Hinduism from Gandhi’s ‘passive resistance’ and colonial conceptions of the ‘effeminate native’. Instead, it aligns with the nationalist and global aims of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who emphasizes the importance of Hindu traditions and physical fitness for collective prosperity. While these new epic adaptations certainly broaden the reach of Hindu culture beyond national boundaries, I suggest exhuming only warrior narratives from the epic texts oversimplifies Hindu values and threatens a range of gender identities and religious affiliations. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta The Refugee Woman: Partition of Bengal, Women, and the Everyday of the Nation by Paulomi Chakraborty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Film Studies ©Paulomi Chakraborty Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Re-Writing the Myth of Draupadi in Pratibha Ray's Yajnaseni and Chitra

Athens Journal of Philology - Volume 7, Issue 3, September 2020 – Pages 171-188 Re-Writing the Myth of Draupadi in Pratibha Ray’s Yajnaseni and Chitra Bannerjee Divakaruni’s The Palace of Illusions By Mohar Daschaudhuri* All history, accounts of religion, social thought and philosophy reflect woman as the “other” even while speaking for her. Myth constitutes the elemental structures and patterns which shape the thought of a people. This paper explores how Pritabha Ray‟s novel Yajnaseni and Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni‟s The Palace of Illusions re-write the myth of Draupadi, the legendary wife of the five Pandava warriors in the epic Mahabharata. The two contemporary women writers from India recreate a protagonist who voices her opinions, musings, desires in a first person narrative from a woman‟s point of view. As upholder of Dharma, she is at once a player and a pawn in the patriarchal tale of jealousy and revenge. Yet, remaining within the bounds of Dharma, Draupadi, the protagonist in the novels, interrogates the symbolic values attributed to femininity, the meaning of duty, loss and death. Through a feminist re-reading the authors redefine the notion of Svadharma (an individual‟s duties) vis-à-vis the duties of a woman towards her husband and her society. The re-invented myth resists „spousification‟ and deification of the woman, rendering her instead, a palpable character, vulnerable as well as independent. While Ray‟s character is in a search of a spiritual rebirth and relies on her inner deity, Krishna, for guidance all along the tortuous path of Dharma during her life and after her abandonment by her husbands, Divakaruni‟s heroine is a modern day adolescent, impetuous, intelligent and spontaneous. -

Pratibha Ray's Yajnaseni

http//:daathvoyagejournal.com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department of English Dr. K.N. Modi University, Newai, Rajasthan, India. : An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in English ISSN 2455-7544 www.daathvoyagejournal.com Vol.1, No.4, December, 2016 Pratibha Ray’s Yajnaseni: The Story of Draupadi as a Study in Feminist Revisionist Re-writing Dr. Panchali Mukherjee Associate Professor and Head of the Department of Languages T. John College , Bangalore 560066 Email: [email protected] Abstract: The research paper “Pratibha Ray’s Yajnaseni: The Story of Draupadi as a Study in Feminist Revisionist Re-writing” will explore the idea of ‘Feminist Revisionist Re-writing’ or ‘Feminist Revisionist Mythology’ in the light of the translated version of Pratibha Ray’s Yajnaseni: The Story of Draupadi (1995) by Pradip Bhattacharya. It studies the role of Yajnaseni or Draupadi as presented in the text from a feminist perspective thereby countering the male biases that have coloured her presentation in the epic or in mythology since time immemorial. It will attempt to show the way in which the above mentioned text asks new questions in relation to Yajnaseni. It will describe the way in which this text rediscovers the character of Yajnaseni, resists sexism in literature and increases awareness regarding the sexual politics prevalent in the society. The research paper shows the way in which the text dismantles the literary convention to reveal the social ones and invert both by making the ‘Other’ into the primary subject. The paper also attempts to show the way in which ‘Revisionist Mythmaking’ is a strategic revisionist use of gender imagery and is a means of exploring and attempting to transform the self and the culture. -

Master of Arts in English (MAEG)

This course material is designed and developed by Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), New Delhi. OSOU has been permitted to use the material. Master of Arts in English (MAEG) MEG-07 COMPARATIVE LITERATURE Block-6 LITERATURE AND CULTURE: EXCHANGES AND NEGOTIATIONS-I UNIT-1 TELLING AND RETELLING UNIT-2 RETELLINGS OF MAHABHARATA UNIT-3 DHARAMVIR BHARATI’S VERSE PLAY ANDHA YUG EXPERT COMMITTEE Prof. Indranath Choudhury Prof. Satyakam Formerly Tagore Chair Director (SOH). Edinburgh Napier University School of Humanities Prof. K. Satchidanandan (English Faculty) Academic, Poet, Translator, Critic Prof. Anju Sahgal Gupta, IGNOU Prof. Shyamala Narayan (retd) Prof. Neera Singh, IGNOU Formerly Head, Dept of English Prof. Malati Mathur, IGNOU Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. Prof. Nandini Sahu, IGNOU Prof. Sudha Rai (retd) Dr. Pema E Samdup, IGNOU Formerly Dean, Department of English Dr. Parmod Kumar, IGNOU Rajasthan University, Jaipur Ms. Mridula Rashmi Kindo, IGNOU Dr. Malathy A. COURSE COORDINATOR Prof. Malati Mathur, School of Humanities, IGNOU BLOCK PREPARATION Course Writers Block Editor Prof. T. Sriraman (retd) Prof. Malati Mathur Formerly Dean, English Studies School of Humanities The English and Foreign Languages University IGNOU Hyderabad Dr. Swaraj Raj (retd) Associate Prof. and Head Postgraduate Dept. of English Govt. Mohindra College Patiala (Punjab). Secretarial assistance: Ms. Reena Sharma Executive DP (SOH) PRINT PRODUCTION Mr. C.N. Pandey Section Officer (Publication) SOH, IGNOU, New Delhi May, 2018 © Indira Gandhi National Open University, 2018 ISBN-978- All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the Indira Gandhi National Open University. -

Yajnaseni: the Plight of a Woman

www.the-criterion.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Yajnaseni: A Synonym of Indian Woman Dr. Sanchita Choudhury HOD Dept. of Humanities, Padmanava College of Engineering & Sagarika Dash Lecturer Dept. of Humanities, Padmanava College of Engineering यत्र नाय셍:तु पू煍यꅍते रमꅍते तत्र देवता: | यत्र एता: तु न पू煍यꅍते सवा셍तत्र अफला: �क्रया: || -मनुमॄ�त (Transliteraion: Yatra naryastu pujyante ramante tatra devata/ Yatra etᾱh tu na pujyante sarvasttra aphalᾱh krtiyᾱhi) [Translation: Women are honored where divinity blossoms; wherever women are dishonored, all action, no matter how noble, remain unfruitful.] Indian tradition has been considered unique in many aspects. It is said to be different with respect to its association of day-to-day lifestyle and professional life with philanthropy. It has awarded highest regard to a woman considering her a mother, who is regarded as the epitome of purity and inviolability. India has always had a special place for women in almost every ritualistic practice in the society. A woman is free to take part in any spiritual and social service unlike many cultures in the society. And women from time immemorial have exhibited their dynamic energy, devout efforts and committed service for their family, society and every other field where they received an opportunity or platform to perform. Indian aesthetics, philosophy and tradition have expounded various qualities of women. The ultimate reality is one and the world of beings is its manifestations. The Upanishads declare that “ekam sat vipraha bahuda vadanti” (There is but only one reality in this world). Man and woman are the two manifestations of one supreme power. -

Rewritings / Retellings of Indian Epics I: Mahabharata the Lecture Contains

Objectives_template Module 9:Translating Religious Lecture 33: Rewritings / Retellings of Indian Epics I: Mahabharata The Lecture Contains: Introduction The Mahabharata Retellings in Other Languages Modern translations Works Based on the Mahabharata Inter-semiotic renderings Influence on language and culture file:///C|/Users/akanksha/Documents/Google%20Talk%20Received%20Files/finaltranslation/lecture33/33_1.htm [6/13/2012 10:48:50 AM] Objectives_template Module 9: Translating Religious Lecture 33: Rewritings / Retellings of Indian Epics I: Mahabharata Introduction Continuing our discussion of the translation of religious texts,it is not quite correct to compare the Bible or Quran with the epics in India. The texts of such religious significance for Hinduism are the Vedas which were composed in Sanskrit. There were injunctions not just against the translation, but even the recitation of Vedic mantras by lower caste people who did not know Sanskrit. Here we again see the attempt to jealously preserve scriptural knowledge without allowing it to be accessed by all. Knowledge of Sanskrit was restricted to the educated few which consisted only of upper caste men. Dash and Pattanaik note: “The Vedas, Vedangas, Smrutis, Darshanas, Samhitas and Kavyas written in Sanskrit were meant to have the function of ratifying the worldview of the ruling class and of the Brahmin clergy. The Brahmins used their knowledge of Sanskrit as an irreducible form of power, and translation was not encouraged since it would have diluted the role the texts could have played as a part of such an officially- sponsored ideology” (134). It was believed that the Vedas were of divine origin and translation into an ordinary language would have been similar to defiling it. -

Ruminations: the Andrean Journal of Literature

ISSN 2249-9059 Ruminations: The Andrean Journal of Literature Vol. 2 Editors: Dr. Marie Fernandes Principal and Head Department of English Dr. Shireen Vakil Former Head Department of English Sophia College Prof. Susan Lobo Asst. Professor Department of English St. Andrew’s College St. Dominic Road, Bandra, Mumbai 400 050 © 2012 Dr. Marie Fernandes Published: August 2013 St. Andrew’s College Bandra, Mumbai 400 050 Printed by J. Rose Enterprises 27 Surve Service Premises, Sonawala X Road, Goregaon (E), Mumbai 400 063. ISSN 2249-9059 Index 1. Myth and Cult in Literature Marie Fernandes 1 2. The Myth of India in History, the American Classroom, and Indian-American Fiction Dorothy M. Figueira 9 3. Our Mother Ground: Seamus Heaney’s use of Myth in Wintering Out and North Shireen Vakil 12 4. The Fictionalised Life of Alexander the Great in the Novels of Valerio Massimo Manfredi Shreya Chatterji 17 5. Greek Mythology in English Literature Harry Potter’s Greek Connection Sugandha Indulkar 25 6. Mythological Exploration in the Thousand Faces of Night, Where Shall We Go This Summer and A Matter of Time Ambreen Safder Kharbe 35 7. Problematizing R.K.Narayan’s Use of Myth in the Man-Eater of Malgudi Lakshmi Muthukumar 47 8. The Archetypal LaxmanRekha in Rama Mehta’s ‘Inside the Haveli’ Muktaja V. Mathkri 53 9. Mythicising Women who make a Choice: A Prerogative of the Indian Collective Unconscious to Demarcate Modesty and Right Conduct for Women Shyaonti Talwar 63 10. Mythic reworkings in Girish Karnad’s Yayati and The Fire and the Rain Sushila Vijaykumar 71 11. -

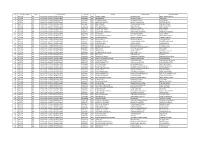

Sl# District Name Sub College Name

SL# DISTRICT NAME SUB COLLEGE NAME ROLLNO CAT NAME FATHER NAME MOTHER NAME 1 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA001 GEN ANWESHA PATHI SRINIBAS PATHI MADHUSMITA MISHRA 2 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA002 GEN SABNAM ARRA MD SAKIR HOSSEN SAJIDA BIBI 3 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA003 GEN SATABHISA NAYAK SATYABRATA NAYAK PUSPA NAYAK 4 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA004 GEN SABIR KUMAR BARIK BISHNU PRASAD BARIK MATHURA BARIK 5 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA007 GEN ARATI MISHRA AKSHYA KUMAR MISHRA CHAPALA MISHRA 6 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA009 GEN SIDDHANTA DAS NARAHARI DAS SANDHYARANI DAS 7 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA010 GEN DURYODHAN SWAIN INDRAMANI SWAIN CHINA SWAIN 8 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA011 GEN MAHALAXMI PARIDA RAMACHANDRA PARIDA KUNI PARIDA 9 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA014 GEN SUBHASHREE DANDASENA ABHIMANYU DANDASENA MAMATA DANDASENA 10 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA015 GEN MITA SAHOO DURYODHAN SAHOO GOLAP SAHOO 11 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA016 GEN PRAJNA PARAMITA PARIDA KAILASH CHANDRA PARIDA BISHNUPRIYA PARIDA 12 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA017 GEN PRAGATI PRADHAN PRASANA PRADHAN JYOSTNA PRADHAN 13 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA020 GEN MITALI PRUSTY KANDARPA PRUSTY SUBASINI PRUSTY 14 KHURDA ART B J B JUNIOR COLLEGE, BHUBANESWAR 103MA023 GEN NARMADA PRADHAN GANGADHAR -

The Difficulty of Being Good

+ The Difficulty of Being Good + + + + ALSO BY GURCHARAN DAS NOVEL A Fine Family (1990) PLAYS Larins Sahib: A Play in Three Acts (1970) Mira (1971) 9 Jakhoo Hill (1973) Three English Plays (2001) NON-FICTION India Unbound (2000) The Elephant Paradigm: India Wrestles with Change (2002) + + + The Difficulty of Being Good On the Subtle Art of Dharma Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2009 by Gurcharan Das First published in Allen Lane by Penguin Books India 2009 Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Das, Gurcharan. The diffi culty of being good : on the subtle art of dharma / by Gurcharan Das. p. cm. Originally published: New Delhi : Allen Lane, 2009. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-975441-0 (pbk.) 1. Mahabharata—Criticism, interpretation, etc. 2. Mahabharata—Characters. 3. Dharma.